Desire, Sexuality And Choice: Disabled Indian Women And Queer Persons On Their Experiences

- Geetika Mantri

When they were 18, Nu, a non-binary person with physical and speech disabilities, recalls apologising often to their dates: “I’m sorry I walk with a crutch. I hope that’s ok with you.”

Nu recalls feeling coerced to do unwanted things, just to hold on to a partner: “I found myself feeling grateful that someone liked my ugly, disabled self.” However, in the last five years, Nu, who has since founded the Revival Disability Community and magazine, which highlights narratives of disability and sexuality, has learned to take up space. “It has been – and is – a long journey to be disabled and alone,” they said.

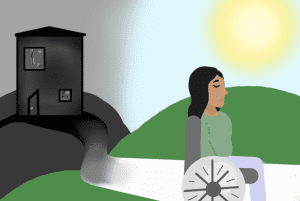

This is a familiar experience for the many women and queer persons with disabilities we interviewed – a sense of obligation to hold on to people who expressed desire for them. In a country where sexuality and desire are rarely talked about, and where pleasure is believed to be the domain of able bodies, disabled persons say they find themselves in the margins.

India’s disability movement largely neglected these issues till recently because it had largely focused on social change issues such as accessibility, inclusion, and reservation, noted scholars Renu Addlakha and Mahima Nayar in their paper, ‘Disability and Sexuality: Intersectional Analysis in India’. “Failure to take into account the ‘body’ means that issues related to desire, attractiveness, relationships, intimacy, marriage, reproduction, parenting, etc. are not given enough attention,” they wrote.

As a result, disabled persons are considered unattractive and sexless, and find it hard to access support, resources and enabling spaces to express and explore their sexuality.

Body image and desire

Vrinda*, a young woman with multiple disabilities, grew up believing that she has no sexual needs and desires. “I felt I shouldn’t be aspiring to intimacy because my body and my health are fragile,” she said. Sexual acts started to feel like a chore, leaving her body in pain. She wondered if she was really feeling the fatigue or if, as some of her partners alleged, she was “using pain as an excuse”.

Social norms and popular culture deny women and queer persons, doubly marginalised due to gender and sexual identities, the enabling lens to look at their own bodies. “For women with disabilities the imperfect body comes to signify absence of femininity; since they may not look like ‘normal women’ and their bodies may not function like ‘normal bodies,’” noted gender scholars Anu Aneja and Shubhangi Vaidya in their book, Embodying Motherhood: Perspectives from Contemporary India.

However, as disabled activist Malini Chib points out in the book, “disability does not hamper a person’s emotional need to be touched and loved on an emotional and physical plane just like everyone else. Our sexual organs are not damaged or affected, and hence we do long for and are able to enjoy pleasurable sexual experience.”

But widespread social attitudes affect how disabled persons see themselves in this context, said Madhumitha Venkataraman, founder of Diversity Dialogues, a collective that counsels individuals and organisations on diversity and inclusion. “My experience while working with persons with disability has been that our identity of being a sexual or even a romantic being is often invisible. It becomes invisible to such an extent where we end up invisibilising it for ourselves as well. I think the challenges are more for women, though it has been similar for men as well,” said Venkataraman.

Not just ‘functional’ bodies

Venkataraman, who lives with an orthopaedic disability, also wrote about her experience of growing up with disability in 2017 for White Swan Foundation, a now-defunct mental health advocacy organisation. She was always encouraged to nurture a sense of self-worth but when she hit puberty, weight gain and her inability to participate in sport, left her feeling “not beautiful”. Unrealistic standards of beauty for women have an aggravated impact when a woman is disabled, she said.

“Since people with disability are largely believed to be asexual beings; their exploration of their own body and that of others could be very limited. This leads us to believe that our bodies have a certain functionality and they are not meant to be enjoyed or lived with,” Venkataraman wrote.

This leads disabled persons “to separate their bodies from their selves, view their bodies and lived experiences as different from others, and often disregard their own knowledge and strengths”, wrote Abha Khetarpal Maurya, a disability rights activist and counsellor, in her 2017 piece for the blog Sexuality and Disability.

The conversations around sexuality are male-centric, such as the boundaries between pain and pleasure, said Vrinda. After her previous partners demanded sexual acts that were painful, the turning point came with a partner who was willing to have conversations about her feeling of inadequacy about her body.

“I realised that my body could do a lot when it had the support and care. My body is capable of pleasure and desire like anyone else’s. Having a partner who was willing to put in that extra care, helped me appreciate my body and not blame it,” said Vrinda.

‘Not looking for a caretaker’

Internalised perceptions often force disabled persons to stay in unfulfilling or even abusive relationships, we found.

Nu, who has dated cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied men until now, shared their experience: “I was once having an argument with a guy at a mall. When an able-bodied couple fights, one of them can just leave the space and walk away. But I had to think ‘if he left, how would I get home? I needed his help to move.” This meant tailoring a response that would not annoy the man.

In romantic relationships, there is often emphasis around a person “accepting” their partner’s disability. Soumita Das, founder of the Zyenika which makes adaptive clothing for persons with disabilities, wrote about her experience in a blog, “Can we ever have a conversation about desire without centering my disability?”.

Das, who has a severe form of arthritis and is a wheelchair user, was proposed marriage by her physiotherapist. While professing his love, he made it a point to mention that he wanted to “accept” her despite her disability. “I wondered what he could possibly know about who I am in order to accept me as I am, and confidently propose marriage without even first asking me on one date,” she wrote.

Samidha (23) lives with multiple disabilities including chronic pain, fibromyalgia, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which affects connective tissues and impairs mobility. She was so overwhelmed by gratitude when someone expressed interest in her for the first time, at the age of 15, she felt she could not say “no”.

“I never stopped to think whether I liked them or not. I was just glad that someone liked me. I didn’t feel I had the right to say no. I thought ‘I will figure out how to like them too,’” said the editor with Revival Disability Magazine. Living with multiple invisible disabilities also meant the dread of having to explain these to her dates.

Society, family and friends often reiterate the idea that disabled women should unconditionally reciprocate romantic and sexual interest when it comes their way. In 2020, Srishti Pandey, a then 22-year-old MA psychology student, wrote for Love Matters of her friend’s reaction to a Class X boy messaging her when she was in school. She suggested that Pandey respond favourably to the exchange (which included the boy remarking that she was “too cute to be in a wheelchair” and that he was “willing to date her”). The response had left Srishti shocked and hurt.

“According to my friend, I didn’t have a lot of ‘chances’ at love like my non-disabled friends,” she wrote. However, she added, she did not want a “caretaker” for a boyfriend. Her ask is quite simple: “I wish for a partner who is ready to let go of his inhibitions and is willing to learn about my likes, dislikes and even my quirks.”

Inhibited intimacy

For Ritika* (28), who has progressive deaf-blindness, dating and relationships were unthinkable as long as she lived with her conservative and protective family. After she moved out, she dated a man for six years, and found herself craving for the conventional – marriage, home, family. After the couple parted ways, Ritika is wary of going down that road again.

“I do crave a relationship and marriage, but I also feel fed up by the whole thing,” said Ritika, who works with an organisation that provides services for children with deaf-blindness. She is cautious about dating and matrimonial apps too. She wants to adopt a girl child but worries if she would be able to communicate well with her child because of her disability.

Even disabled persons with more access and freedom – such as to date – are faced with other hurdles. For Nu, their disability shrunk the space they had to explore their gender and sexuality. Living in Gurugram, Nu feels the lack of safety even more profoundly because of the absence of disabled-friendly infrastructure in the city. And though they want to, they feel unsafe to explore casual sex. “I worry that I will be unable to escape if they violate me,” they said.

Romantic relationships often seem like the only way to explore desire for many disabled persons. “In some way, for disabled folks, romance and sexuality become tied. There is perceived safety in romantic relationships,” said Nu, who added that they want to place romantic relationships “at the bottom of the hierarchy” and focus on their work. “If I weren’t disabled, I probably wouldn’t think this way. The access to dating, having a rebound, moving on, marriage is just harder for us.”

Artist and writer O Aishwarya, however, found freedom in online dating. Filled with apprehensions about safety and her ability to swipe right on someone without being able to see their photos, she decided to explore the dating app Tinder.

She spoke about her experiences on the app in a video for Pyaar Plus, a sexuality toolkit for young people with disabilities and those around them, curated by Point of View, a non-profit that focuses on intersections of disability, sexuality, and technology. People were shocked to find a disabled person set up a dating profile to seek casual relationships instead of long-term ones, she said.

Aishwarya disagreed with the notion that many disabled people see themselves as unworthy of being dated. “Of course, not all people I met online were nice. Not all of them wanted to go out with me. Some of them did say ableist things. But, as time passed, it hurt me less and less. Their comments were nothing compared to the many people I had met up with who did not see anything wrong in dating a disabled person,” she said.

Exploring marriage

Seema* (24), a student of vocational training at Vidya Sagar Centre for Special Education in Chennai, lives with intellectual disabilities. She often asks her mother, “why are people my age getting married and I am not.” We asked her why she wanted to get married. “We will be happy,” she says simply.

Conventional and patriarchal thinking has made it so that marriage provides women social security, which explains why it becomes aspirational for disabled women as well, studies say. Marriage also becomes a “legitimate” space to explore sex and sexuality.

For disabled persons, especially those with psychosocial disabilities, marriage has less to do with intimacy, companionship, and sexuality, notes the paper Sexual Rights of Women with Psycho-social Disabilities: Insights from India. “Some of the primary motives include marriage as a cure for illness, a source of unpaid long-term care, assurance for old age, and so on.” This is particularly true for disabled men for whom marriage to socially “undesirable” women, those widowed or divorced, or those with a lesser degree or hidden disability is seen as a solution for long-term care.

It is different for women living with disabilities who are not seen as “worthy” investments by families, noted Renu Addlakha. So, families may conceal the woman’s disability, especially if it is invisible as in the case of a psycho-social disability, to get her married. But, she added, once marital families discover the disability, and possibly her inability to perform gendered roles, it could lead to abuse, abandonment, or even the annulment of the marriage. Even for disabled women who have social and economic privileges such as a good education and job, the escape from the gendered expectations – to give birth or manage household chores – becomes difficult, said Venkataraman.

Sometimes conversations about marriage do not include the women themselves. Shikha*, a student in Delhi in her early 20s who lives with a locomotor disability, says people tend to talk over her in this regard. “People address my family instead and from a point of concern. ‘Who will marry her?’ they ask,” she said. Her mother had often warned her that people may “use” or “exploit” her or be with her out of sympathy. “I don’t think she is entirely wrong,” she said.

But conversations around disability and sexuality are now growing. Nu demands more spaces where disabled persons, including queer individuals, can be themselves, express anger and all emotions that make them human. “I would like to work towards a world where someone like me could also be a Carrie Bradshaw from Sex and the City,” Nu said.

*Names changed to protect identity

[This is the sixth report on the series on violence and exclusion faced by women and trans persons with disabilities in India as part of the Spotlight Media fellowship. The fellowship is a collaboration between Rising Flame and BehanBox. You can read the previous reports here, here, here, here and here.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.