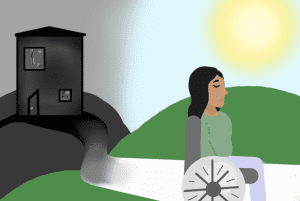

Women With Disabilities Have To Constantly Negotiate Between Isolation And Intrusion

- Flavia Lopes

Barely a month before her 12th grade board exams, Kavya Mukhija (now 23) had to take a week’s sick leave from school. She had contracted a severe urinary tract infection because she was not able to access the washrooms at her school.

Mukhija lives with Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita (AMC), a locomotor disorder caused by joint contractures and muscle weakness. When she was at school, one of her parents had to accompany her after she had been assisted into a wheelchair. There were few spaces she could access at school.

During her periods, the teen missed school for a day every month. “The fact that I couldn’t use washrooms itself caused so many complications and when I’d be on my period, it became super difficult,” recalled Mukhija.

In India, almost every public space, building and utility – schools, colleges, universities, train stations, bus stops, metros, public toilets, gardens – is built for the non-disabled. All the critical life decisions of disabled persons are restricted by how these spaces work for them: where to live, which institution to pick for studies, who to work for or what sort of leisure activity to engage with. The problem is even more acute for women.

“For women with disabilities, the experience is compounded because inaccessibility makes you vulnerable to abuse. You have to allow a stranger into your personal space, to hold your shoulder or hand and lead you across the street. And families imply that it is a non-disabled person’s world, that because there is inaccessibility, there will be safety issues. This also leads to very reduced participation [in public spheres], which means that you see very few disabled women in public spaces,” said Nidhi Goyal, a feminist and disability rights activist and the founder-director of Rising Flame, a non-profit organisation that works with people with disabilities, especially woman and youth. “So, while accessibility means participation, independence and productivity, inaccessibility puts us (women with disabilities) in a constant space of negotiation between being safe and participating in society, between being protected and being independent, between consent and violation of consent.”

Stepping out into the street has to be a thought-through decision for disabled women, pointed out Michele Friedner, assistant professor at the University of Chicago. “There is no idea of leisure for women with disabilities,” said Friedner, who has researched on India’s deaf and disabled communities of India and is herself a deaf individual.

Upto 1 billion people, an estimated 15% of the global population, live with a disability, according to a 2011 comprehensive report by the World Health Organization (WHO). India is home to about 26.8 million people with disabilities, almost half of them women, as per Census 2011.

When ‘help’ is intrusion

When Aishwarya Othena started working, many told her that being blind would be a hindrance. But she took the job, moving to Bangalore from her home town in Kerala. Her work, with an organisation for the visually impaired, involved travelling around the city. But her biggest problem was being offered unsolicited help. She recalled being grabbed, pushed and pulled even when she did not seek any assistance.

“You have to be polite and not rude because people claim to be ‘helping’ you. But where is my consent? Nobody asks me if I want help or not,” she said.

Women with disabilities often experience harassment under the guise of assistance, especially at the time of boarding or disembarking a vehicle, said a report released on November 16, 2021 by the Ola Mobility Institute, a policy think-tank working at the intersection of mobility innovation and public good. Even in relatively accessible utilities such as Delhi Metro, women with disabilities have male helpers assigned to them. Unlike non-disabled women, in the event of a threat, they may not be able to escape to safety or raise an alarm.

“Physical touch can mean so many things, it can mean a touch of care or touch of intrusion and abuse. And, the distinction between the two is very difficult [to explain],” said Apoorv Kulkarni, who heads the accessibility and inclusion tract at the Ola Mobility Institute.

For women with disabilities, accessibility and safety go together, said Goyal: “In order to be safe, women with disabilities need to understand their surroundings. If it is not accessible, it is not safe.”

Isolation as well as intrusion

We noted in our conversations with women with disabilities that they experience social isolation and the invasion of privacy simultaneously. Their body becomes available to other people — parents, doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, groups of medical students doing the round of wards, for example.

But reduced access also means that people with disabilities are not able explore or conduct social relationships with ease. Othena spoke of the difficulties of going out. “Coming home is a nightmare. I mean, there are so many bus routes I get really scared I could end up in the middle of nowhere,” she said.

Kanika Agarwal, who is postlingually deaf (loss of hearing after learning to speak), said that if you ask for occasional help from friends or family it is assumed that you are perpetually dependent. This prevents her from seeking help, she said. What is even harder is seeking help with communication that is personal in nature. “Having to involve family and friends makes me feel vulnerable and bereft of privacy,” she pointed out.

In April 2021, the Supreme Court noted in a case related to the rape of a blind Scheduled Caste woman, that “women with disabilities, who inhabit a world designed for the able-bodied, are often perceived as ‘soft targets’ and ‘easy victims’ for the commission of sexual violence”.

Legal and policy frameworks

The cost of excluding persons with a disability can be as high as 3-7% of a country’s GDP, according to the International Labour Organization. Given India’s forecasted GDP of approximately $2.8 trillion (Rs. 214,816,00 crore) in 2021-22, this could mean a lost opportunity of nearly $232 (Rs. 177,957,9 crore) billion.

“Inaccessibility renders a person with disability invisible, it leaves them out of context,” said Kulkarni of the Ola Mobility Institute. “More importantly, in an inaccessible environment, disabled people, especially women, who choose to be independent, almost pay [something] like a disability tax. Their opportunities to earn are probably not as equal as non-disabled individuals and they have to spend and invest more in their everyday requirements. Plus, their future prospects are severely constrained because they aren’t able to get to a school or college of their choosing due to accessibility issues.”

Since the 1990s, accessibility for those with disabilities has been prioritised within the global policy framework. The United Nations General Assembly recognised the importance of providing equal opportunities for disabled individuals in the context of development. In 1993, the UN General Assembly adopted the Standard Rules on Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities.

India became a signatory to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in October 2007. Article 9 of UNCRPD obliges signatories to take measures to ensure persons with disabilities access to their physical environment, transportation, information and communication and other facilities and services.

But India has failed to adopt many of these mandates.

Roadmap lacking

In December 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the nationwide Accessible India campaign to improve the accessibility to built environment, transportation, and information and communication systems. Accessibility audits were to be conducted at all the international airports, railway stations and government-owned public transport carriers in the country and they were to be made fully accessible by March 2018.

“The Accessible India campaign started with a lot of fanfare and set targets. The latest timeline is for June 2022. But not enough has happened. To implement this the entire ecosystem needs to participate and the government needs to issue clear guidelines, notifications that will require actors to deliver on certain accessibility measures and penalties should be issued. The campaign set targets, like 25% by a certain year, but the financial allocation has not been adequate to make a meaningful difference at scale in a time-bound manner,” Kulkarni said.

In 2016, the government drafted the Right of Persons with Disability (RPD) Act, which replaced the 1995 People with Disabilities Act and mandated that all private and government institutions and establishments should ensure barrier-free spaces and services for people with disabilities. Section 41 of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 stated that the government would ensure that persons with disabilities would have access to all modes of transport that conform with “design standards” (designs of products and services that can be used by the maximum number of people). This would include retrofitting of old modes wherever technically feasible and making it safe without entailing major structural changes. The government is also expected to take suitable measures to provide facilities for the disabled at bus stops, railway stations and airports.

“Under the RPD Act, the government has to frame standards on accessibility for not only government entities but also private entities providing services to the public, including in areas such as educational and vocational, employment, shopping, banking, communication, and access to justice by June 2019. So far three notifications have been issued. But many service providers have not yet brought their practices in line with the law,” said Rahul Bajaj, senior resident fellow at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

In November 2021, the road transport and highways ministry issued a new draft notification titled “accessibility guidelines for bus terminals and bus stops”. Among other things it mandates reservation of places for persons with disabilities within 30 metres of the entrance of bus terminals. A uniform set of norms were to apply in all states.

“The problem with these notifications is that they themselves are not accessible for people with disabilities. Many of these notifications are as image-based pdf’s, not text-based pdf, which makes them unreadable for screen reader users,” said Bajaj.

In the 2017 case of Rajive Raturi vs. Union of India, the court discussed at length the accessibility requirements of persons with visual disabilities with respect to safe access to roads and transport facilities. The court found that the tasks and activities planned and initiated by the governments under the Accessible India campaign were not comprehensive enough and did not adhere to the time frames provided for in the 2016 Act.

States too are working on improving access to transportation. In January 2019, the Delhi Government announced the addition of 1,000 buses fitted with hydraulic ramps to the existing fleet of 3,750 accessible buses. In June 2019, the Chief Minister of Goa launched wheelchair-accessible school buses for students of the Sanjay Centre for Special Education, a school for disabled children, to reduce the dropout rate among students using a wheelchair.

“There are interventions to improve accessibility of a train station or make a percentage of buses more accessible, but these isolated interventions may not be enough to deliver improvement at scale, said Kulkarni. “Transport planners need to adopt a trip chain lens. Accessibility improvements need to be prioritised across physical and digital infrastructure of the mobility ecosystem.”

“We can’t really de-alienate digital and physical accessibility because helplines are online. And if a deaf person won’t be able to call, how will that person access justice?” asked Goyal.

Staying hyper-aware in public

A nagging anxiety sets in whenever she steps out, said Mukhija. Other women we spoke to also talked about being in a state of hyper-alertness when they are outdoors. “What if something happens? How safe am I? What if they are trying to help me but I misinterpret it as an ill-intentioned act? My parents have never expressed this but I feel they might have these questions in their minds too,” said Mukhija.

Even during a day commute, Othena said she found it hard to relax. “I cannot wear earplugs to relax because it is like one more sense is muted,” she said. “I have to constantly check Google maps to see that I am not in any isolated place.”

For Shishna Anand, a person with deafblindness, the only mode of communication with people around her is tactile sign language, and she said she wished she had at least partial vision or hearing ability so she could be a little more independent.

Striving for independence

Independence has particular implications for women because conventionally they were expected to be dependent. Those with disabilities struggle for control over their own destinies, although they are sometimes “allowed” to step out of the passive and dependent female role.

Further, dependence is often manifested in material poverty and a loss or lack of income. “Women with disabilities often get locked out of participating in financial transactions because of inaccessibility. For instance, even negotiating a fair price for hailing an auto is difficult,” said Kulkarni.

Mukhija has never been to any banks or even an ATM kiosk because they are inaccessible. Bank executives help her with the formalities at home in front of her parents.

Bank websites are a “gruelling maze”, said Strutilata Singh, who lives with deafblindness. “Financial independence becomes a living nightmare when these apps remain inaccessible to us and we constantly need to depend on others [to use them]. The digital revolution may have eased spending, but for people with disabilities it is stuck in a place of struggle, reinforcing [the cliche] that people with disabilities need a support person,” she said.

Access brings inclusivity, helps all

When Neha Arora was young she could not travel during vacation as her father was visually challenged and her mother needed the wheelchair. “Our family is very fond of travelling and the one thing that bothered me most was that accessibility was a huge issue,” she recalled. It was this realisation that inspired her to set up Planet Abled – a travel company that caters exclusively to the needs of disabled people. “The very idea behind our initiative is that travel is not a privilege, it’s a basic human right,” said Arora.

Finding hotels with multiple accessible rooms, activities that can be enjoyed by persons with disabilities – these are all challenges, said Arora. “But we are getting there,” she said. Panet Abled made an accessible car for Deepa V, a woman with a locomotor disability, and she has been using it for the last couple of years.

Though infrastructure in India is being transformed to focus on better access, it is a slow process and one that is limited by “a checkbox mentality – you make something accessible, check the box and then you end there”, said Friedner. “Accessibility or to access something does not have a fixed definition. To access infrastructure, does not necessarily mean the built environment but also to have access to people. For instance, allowing a porter to carry you. While under international standards, this is not accessibility, but in India, it comes under accessibility.”

Clear and prominent signages over accessible facilities are critical in offering assurance and confidence to everyone, and not only persons with disabilities. “If we as a society continue to see buildings which are accessible, like signages, ramps, elevators with Braille and embossing boards, we know that this space belongs to all. For instance, the moment you spot a women’s washroom, you know women will be there even if not at the moment,” said Goyal. “Accessible infrastructure is used by all and not just people with disabilities. For instance, vibrations on mobile phones were introduced for deaf people but today everyone uses them. Ramps were for wheelchair users, but today all, including pregnant women and children use them.”

[This is the fifth report on the series on violence and exclusion faced by women and trans persons with disabilities in India as part of the Spotlight Media fellowship. The fellowship is a collaboration between Rising Flame and BehanBox. You can read the previous report here, here, here and here.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.