‘How will you manage?’ How Disabled Women Are Forced Into Surgical Procedures

- Geetika Mantri

Nearly a decade ago, Smitha*, who lives with cerebral palsy, underwent a surgery to remove fibroids from her uterus. The doctors, at the time, asked if she wanted to get a hysterectomy — a procedure to surgically remove her uterus– done to help her ‘manage’ her period. Smitha, now in her forties, refused. Five years after her surgery, she had a health issue which led her to menstruate for a month at a stretch.

“My family questioned my decision to not get a hysterectomy earlier when I had the chance”, Smitha told Behanbox. “They would not have suggested this to someone with a similar health condition who was not disabled.”

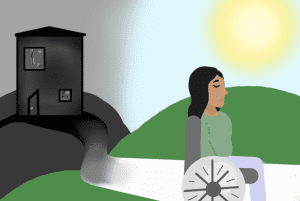

Like Smitha, many women with disabilities are advised, or indeed coerced into surgical procedures under the pretext of convenience and physical safety, violating their bodily autonomy and consent over their sexual and reproductive rights, often by those closest to them.

Women with Disabilities India Network (WWDIN), a cross disability network run by women with disabilities, collected testimonies of women, many of them minors, who were forced to undergo hysterectomies or sterilisations in the ‘Alternative Report’, a document submitted to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities (UNCRPD) Committee in response to the initial report submitted by the government of India. The alternative report collated data from interviews with 441 women with disabilities across 23 Indian states between 2017 and 2018.

The report noted that not only are services like contraception and abortion denied to women with disabilities, especially those with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities, they are also coerced into hysterectomies, sterilisation, contraception and abortions.

“Frequently, when these women are minors or are deprived of legal capacity, guardians, parents, or doctors may make the decision on their behalf”, stated the report. “Even when they are not deprived of legal capacity, they may be pressured to undergo sterilisation based on false assumptions about their sexuality and ability to parent, or based on the desire to control their menstrual cycles.”

India has at least 11.8 million women and girls living with disabilities, according to the 2011 census. These numbers appear to be underestimates, since the census enumerated persons under seven categories, while the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act (RPWD) legislated in 2016 recognises twenty one categories of disabilities.

Sections 10 and 25 of the act stipulate that the state must ensure persons with disabilities have “access to appropriate information regarding reproductive and family planning”, and provide “sexual and reproductive healthcare especially for women with disability.”

Yet, in the absence of disaggregated government data on persons with disabilities, evidence, sparse as it may be, such as the Alternative Report, show that women’s autonomy over their sexual and reproductive health is repeatedly violated by families, caregivers and the medical system.

Forced hysterectomies: A history

The first recorded case of organised forced hysterectomies came to light in 1994 in Pune. That year, the Maharashtra government allowed a team of doctors to conduct the procedure on twenty one women residents of the Government certified School of Mentally Deficient Girls in Shirur area of the city.

The procedure was already carried out on eleven women between the ages of 18 and 35 years, before it was stopped when activist Ahilya Rangnekar brought this to the attention of the then Chief Minister, Sharad Pawar.

In all these instances, parents of the women supported the decision of the institution to conduct the hysterectomies under the garb of managing their menstruation. Dr Shirish Sheth, the gynaecologist who performed the surgeries, was reportedly quoted then by a newspaper, saying that the operations were done to prevent pregnancy in the women, who “often became victims of sexual assault.”

The incident caused widespread outrage, spurring protests by women’s groups and activists, including outside the Sassoon Hospital, where the procedures were performed on the eleven women.

“People are making a big fuss about these operations but you should come and stay with these girls. They all mess up their menstrual discharge. Being anaemic they feel fatigued during their periods”, S.M Sonwane, the superintendent of the Shirur home, was quoted as saying in the Frontline magazine.

Following the incident, a report titled ‘In the Guise of Human Dignity’, looked at conditions in four other institutions for people with intellectual disabilities — Beru Matimand Prastisthan (Pune), Mankhurd Children’s Home (Mumbai), Asha Daan (Mumbai), and Institute of Human Behaviour and Allied Sciences (Delhi). In the first two institutions, there was a tacit expectation that hysterectomies would have to be completed on women before they were admitted to the homes. In all these homes, including the Shirur home, the report’s authors found that the women and girls lived in deplorable conditions of neglect.

“It is glaringly obvious that the hysterectomy option has been chosen because, for the caretakers, it means that much less work, and for the authorities, less expenditure incurred on attendants’ salaries”, stated the report.

The protesting organisations had also pointed out that hysterectomies could even be counterproductive as it could increase the risk of sexual abuse if there was no possibility of finding out about the abuse when pregnancy is eliminated.

The report, put together by several women’s rights groups, took down the ‘hygiene’ and ‘opportunity to live with dignity’ argument offered by Dr Sheth and others:

“Interestingly none of these messiahs of modern science refer to the need for more attendants, trained caretakers, increased budgetary allocations, accountability of staff and officers who run our institutions, more recreational facilities, employment avenues, medical care, psychiatric counselling or simply protecting the rights of handicapped persons.”

In spite of the widespread outrage by women’s groups in 1994, the government of Maharashtra, in 2008, supported a policy of forcibly sterilizing “mentally challenged” women and girls in institutions as a means of ensuring “menstrual hygiene” or the elimination of periods.

Even in 2017, the alternate report prepared by the WWDIN documents forced hysterectomies of minor girls. “In Andhra Pradesh’s Mehboobnagar Block, rural women spoke of hysterectomy as being a common method being used on girls with intellectual disability. At least 20 cases had been documented”, states the report.

25 years after the Shirur incident, Behanbox asked women with disabilities and social workers to understand the prevalence of coercive surgical procedures like hysterectomy or sterilisations. The result painted a different but concerning picture.

‘Safety’ and ‘Management’

Ten years ago, Porkodi Palaniappan, the founder of Better Chances, a wellness centre for people with psycho-social disabilities, met a mother of a pre-teen girl with intellectual disability who wanted to get a medical procedure for her daughter to stop her menstruation.

“The woman, from a rural area, was unable to manage the bodily changes her daughter was going through and was worried about the possibility of sexual abuse. A doctor had recommended that her uterus be removed, so she did not have to worry if she was raped. It was really irresponsible of the doctor ,” said Palaniappan.

Ultimately, the mother decided against hysterectomy after Palaniappan advised her against it.

“But this is a common apprehension since, in our society, the idea of protection comes with the notion of covering up potential sexual abuse rather than preventing it,” she said.

Enquiries to gynaecologists on hysterectomies for young women with disabilities were a common occurrence even a decade ago, said Shampa Sengupta, a Kolkata-based activist working on gender and disability rights.

“Parents were only keen to know if there were medical implications of such a procedure. The concept of consent was alien to them,” said Sengupta.

“One gynaecologist we spoke to, even said that he thought he was doing a favour by performing the hysterectomy on a woman with intellectual disability who was in her twenties,” she says.

In recent years the availability of sterilization methods using certain drugs is being tried out on a large scale instead of teaching the women to manage menstrual hygiene and protecting them from rape, states the alternate report. Despite a government order (GR.No. 24) of 1999, there is no legal provision that prohibits non-consensual sterilization. In 2006, the Ministry of Health issued guidelines for sterilization which state that women and men should be between the ages of 22 and 49 and “of sound state of mind so as to understand the full implications of sterilization.”

Meenakshi Balasubramanian, Associate at the Centre for Inclusive Policy, an organisation that advocates for inclusion of disadvantaged groups in policies and programmes, notes that the notion that disabled women cannot be capable parents, prompts families of disabled women to rob them of the choice.

“The family views a pregnancy which is a result of sexual abuse as an additional responsibility because of their assumption that the woman will be unable to care for the child”, said Balasubramanian. “In the absence of a supportive system, the entire onus falls on the individual,” said Balasubramanian, who is also the co-founder of Chennai-based Equals Centre for Promotion of Social Justice, a disability rights organisation.

The stigma and lack of disability-friendly infrastructure isolates families and caregivers, which is further exacerbated by socio-economic conditions. 69% of disabled population in India lives in rural areas according to the 2011 census with inadequate support, fewer resources and information. In a case documented by the Alternative Report, the parents of a 23 year old woman with an intellectual disability, who worked as daily wage labour, forced her to get a hysterectomy, supported by the doctor, to avoid “unwanted pregnancy”.

Janet Price, a feminist and disability rights campaigner in the UK and India noted in a 2018 report on Sexuality and Disability in the Indian Context by TARSHI , a Delhi-based non-profit working on issues of sexuality, that unlike the western countries where sexuality is an individual issue, southern countries view it as a family or community affair.

Social workers like Sengupta say that queries around forced surgical procedures have dwindled now and attribute this to the passage of the RPWD act among other factors.

A 2017 paper on Disability and Sexuality notes that while the RPWD Act has enlarged the ‘political space for discussions related to disability’, activists also point out that the law has not adequately encouraged debate on women’s sexual and reproductive autonomy.

“The discourse with respect to disability has generally been around employment, education and other familiar aspects, but not so much around the gender dimension and autonomy. The act still subscribes to a guardianship regime,” said Balasubramanian.

Section 92 (f) of the RPWD Act, which lists punishable offences and atrocities against persons with disabilities allows for the termination of pregnancy in ‘severe cases of disability and with the opinion of a registered medical practitioner and also with the consent of the guardian of the woman with disability’.

Enabling autonomy

While forced surgical procedures may have dwindled, the apprehension of parents has not.

“The common question most parents have is ‘how will we train our intellectually disabled child to manage menstruation’?”, said Bahni Bhattacharyya Mandal, a Kolkata-based special educator.

In the absence of vocabulary and accessible tools around menstruation, parents and caregivers are turning to other intrusive surgical methods, violating autonomy and consent.

More recently they have resorted to surgical options like tubal ligation or contraceptive implants and injections. Tubal ligation, a surgical procedure where the fallopian tubes are either blocked or removed, is used to stop pregnancy permanently. Contraceptive implants, where a small device is inserted under the skin which releases progestogen into the bloodstream and contraceptive injections are also being resorted to by families and medical professionals to stop pregnancies. In most cases, the consent of women is never sought.

“This is largely to prevent pregnancy rather than an acknowledgement of the woman’s own sexuality and agency. Some of these women are over the age of 25-30. Many of them are not made aware of what the procedure they are going through is”, said Mandal.

She told us about two instances in recent times where parents of girls with intellectual disabilities resorted to tubal ligation to stop their menstruation. Neither would admit it on record, says Mandal.

It is a popular misconception that girls and women with disabilities cannot learn to manage menstruation and personal hygiene or are unaware of their sexuality. Activists and educators believe that they can be taught early in their life and in tools they are comfortable with. For older women with intellectual disabilities, it may prove to be difficult but not entirely impossible.

Seema*, a 24-year-old with intellectual disabilities and a student of vocational training at Vidya Sagar Centre for Special Education in Chennai, says that she was able to learn about menstruation quite early with the help of the school and her parents.

“My parents and teachers had shown me what a pad was and how it needed to be used before I got my period in class 9. So, I was prepared”, she says.

“Girls with intellectual disabilities need to be taught in a language that they understand, such as with pictures and images if not words”, said Mandal, who has a daughter who is on the autism spectrum with limited speech. Mandal had begun teaching her since she was eight years old about maintaining hygeine, the frequency of changing and disposal of her sanitary pads among other things.

“There are some girls who have very high support needs. But even for them, hysterectomies are not the solution. The onus is on caregivers to manage it,” says Sangeeta Saksena, the co-founder of Enfold Proactive Health Trust in Bengaluru, which has developed a Suvidha kit for children for personal safety and sexuality education.

While there has been some discussion on building a vocabulary in Indian Sign Language on sexuality including menstrual hygiene management, there isn’t enough focus on Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) — modes of communication other than spoken or oral language which uses gestures, visuals, writing, or a speech generating device — used by people with high support needs, says Balasubramanian.

“There’s barely any conversation and research and development on ways of communicating sexual and reproductive desires for people with high support needs. The initiative is restricted to a few NGOs and neither the union nor state governments have taken this up”, she adds.

Disability friendly infrastructure and products are another hindrance in enabling disabled persons’ exercise their autonomy. Almost all women, living with disabilities we spoke to, said that inaccessible and unhygienic public toilets discourage them from venturing out during their menstruation.

Menstrual products are not designed keeping people with disabilities in mind. Smitha tells us her ordeal as a wheelchair user.

“Because I was in a wheelchair most of the time, the pad would move, and I would not be able to adjust it. I had to use two pads and secure them with safety pins. It was dangerous, as the pins could come undone and hurt me.” she said.

“I would tie a thread tightly around my waist to keep my underwear secure so that it doesn’t move along with the pad”, said Silsila, another wheelchair user based in Guwahati, who works as a project coordinator of Bijoyini, a network of women with various disabilities.

Tools around menstrual and reproductive hygiene also need to be accessible and culturally and scientifically appropriate. Enfold’s material which demystifies sexuality, for instance, is available in screen reader-friendly formats. The Suvidha kit contains visuals, puzzles, games, puppets and charts. It is important that the language should not be stigmatising, says Saksena.

“We need to avoid words that have negative connotations when we refer to private parts or menstruation. We need to avoid words like ‘stain’ and instead say ‘blood that comes on the clothes’”, she said, emphasizing that it is important to language that is respectful of our bodies to caregivers, teachers, and boys.

*Names changed to protect identities

[This report is part of the Spotlight Media fellowship. The fellowship is a collaboration between Rising Flame and BehanBox to report on the violence and exclusion faced by women and trans persons with disabilities in India.

Rising Flame is a nonprofit organisation based in India, working for recognition, protection, and promotion of human rights of People with Disabilities, particularly women and youth with disabilities. It is the Recipient for the National Award for Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities 2019.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.