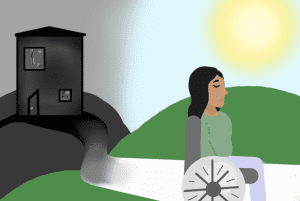

Who Gets To Be A Mother? How Disabled Women Are Absent In The Idea of motherhood

- Flavia Lopes

A few weeks ago, Hera* and her toddler stared at the wall in awe. The light that gleamed through the broken glass pieces of the bangles her son threw on the floor, formed a beautiful pattern on the wall. Mother and son squealed in delight. Just then, a voice screamed:

“Why are you behaving like a child?” It was Hera’s husband.

Hera had heard taunts, censuring her for being ‘child-like’ several times before. “Stop behaving like a child”, “you are an irresponsible mother” and “you cannot handle things” are often hurled at her by her family — taunts that question her ability to mother her child.

Hera is autistic, a developmental disability that affects communication and behaviour. She was first diagnosed with the condition during her first pregnancy. So, when Hera told her close family about her plans to adopt her second child, they were aghast. How could she come up with such a ‘ridiculous’ idea?, they asked.

It is not as if her family does not understand her behaviour or her disability. “But they never understood how to implement that knowledge,” Hera told Behanbox.

Jeeja Ghosh faced similar questions too. In 2018, Ghosh became the first woman with cerebral palsy to adopt a child in India. But when she first went to see the child at an adoption centre in Ghasipur in Odisha, the officials were disapproving of her adopting a child.

“They thought I would be violent and harm the child,” said Ghosh. Her disability affects her ability to move and maintain balance and posture. The adoption centre rejected her application.

Both women’s experiences show that society, as well as the state’s imagination of motherhood for women with disabilities, is centred around their ‘capacity’ to care for their child. This imagination, steeped in prejudices and stereotypes, has been measuring women with disabilities who want to become mothers, with harsh standards of judgement.

“Being nurturing and caring are core components of how a mother is seen, and women with disabilities are themselves in need of care,” says Renu Addlakha, an academic specialising in disability studies. “This inversion has been instrumental in reducing them to less of a mother than an ideal mother.”

This imagination of an ‘ideal’ mother also finds its way into state institutions and excludes women with disabilities in policies, benefits and safety nets crucial to fulfilling the demands of parenthood. Moreover, despite India being a signatory to international conventions such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the laws governing adoption and guardianship are discriminatory for disabled women.

Impossible standards

As a child, Hera had struggled with communication and social skills. She could manage only a few words at a time. The smell of cosmetic products and high-pitched voices would irritate her. She did not pick up signals of hunger. Only when she felt weak or even fainted, did she realise that she had not eaten in a long time.

When Hera gave birth to her first child, she found herself muddling through a fog of exhaustion. Her body had refused to cooperate. It was around then that she found (later diagnosed) that she had autism spectrum disorder, which according to a US-based non-profit Child Mind Institute, often goes undiagnosed in women because the symptoms can be masked and are often interpreted to be something else.

“It was a very difficult time for me. I had a burnout,” she said.

Hera’s son is now three years old. She has to constantly juggle her disability with her family’s expectations of her role as a mother, of which she is always falling short in their estimation. Her mother, for instance, expects her to sit with her son and ask every detail of his day as soon as he returns from daycare, as other mothers do.

“Their (her parents’) constant complaint is that I don’t ask him what he did the whole day. They want me to ask him if he ate well, drank water or even pooped”, she said. “After a long day’s work, not only does my mother flood me with these questions but forces me to actually check his lunch box.”

Hera feels that more than being concerned, her parents are bothered by her inability to “show concern”. “It is not as if I do not care. The thought in my head is that if I trusted and gave the responsibility to the daycare, they would do it.”

For a long time, she found it difficult to articulate why she was unable to show that she cared in the exact ways they wanted her to. She would, nevertheless, do so only to escape her mother’s disapproval. Her husband, whose only reference points are the women he has seen around him, like his own mother, finds it difficult to grasp the fact that she does not behave like them, says Hera.

Dominant narratives of a mother constitute a healthy heterosexual woman, of a certain age, always nurturing and available for her babies. This has meant that ‘ideal’ mothers are expected to be all things, at all times for their dependent children.

“Such a narrative creates an impossible standard for disabled women whose impairments and societal barriers make being a mother much more challenging”, says Addlakha.

Not only are the standards of judgment harsh, but the inability to conform to these societal standards of ‘nurturing’ could lead to the loss of the person’s agency and their authority and consent undermined by families.

When Hera’s toddler’s daycare started a web-cam system for parents to monitor their children virtually, her mother directly contacted the daycare for access, without Hera’s knowledge or consent, so she could observe her grandson.

“Disabled women, in general, are not considered to have the characteristics of ‘good women’ that would deem them fit for marriage, sexual desire or any responsibilities of adulthood”, says Shreshtha Das, a lawyer and queer disability rights activist. “So clearly, motherhood becomes unlikely in such a context.”

State Institutions Fail Disabled Mothers

Jeeja Ghosh and her husband always dreamt of becoming parents. Initially, they wanted to have a biological child. But, when she could not conceive due to her age and disability, they decided to adopt. The initial euphoria, however, gave way to a nightmare.

Despite getting the mandatory clearance from a gynaecologist, they faced intrusive queries over her ability to be a responsible caregiver by the authorities at the centre, when they first applied for adoption in 2016.

“At the meeting in the adoption centre in Keonjhar, Odisha, I was asked if I lost my temper often as I am a ‘patient’ with cerebral palsy”, recalls Ghosh. The officials equated her cerebral palsy with mental illness and concluded that Ghosh would be ‘bad-tempered’, ‘violent’ and would be unable to ‘interact with her child’.

The centre rejected her adoption plea on the ground that the Adoption Regulations 2017 and the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, mandate that the prospective adoptive parents (PAP) “should be physically, mentally and emotionally stable, financially capable and shall not have any life-threatening medical condition.” They, however, refused to give the reason for their rejection in writing.

“I told them that we (she and her husband) both have efficient careers and support at home”, Ghosh told Behanbox.

It was only after Ghosh and her husband wrote to the three-member central adoption committee in New Delhi about their experience, that the process proceeded smoothly. In June 2018, two years after starting the process, Ghosh finally welcomed her daughter, Hiya. The entire experience, however, left her feeling singled out, with mistrust in her capacity to be a parent.

Adoption in India is governed by the Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act, 1956 for Hindus and Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 for other communities. Before the Juvenile Justice Act, non-Hindu individuals could become guardians of children from their community under the Guardians and Ward Act (GWA), 1980 — an act that disallowed a disabled person to become a guardian of a minor if the disability was of a severe nature.

The Juvenile Justice Act and Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act do not have such a provision but they emphasize on the “best interest of the child” in their narrative. The uncertainties posed by the ‘best interest’ standard is well documented in legal commentary on issues involving the rights of disabled parents and also contributes to bias in adoption cases.

“Courts in India often quote that which is ”in the best interest of her (the mother) or the child” to justify who can be a parent. But, the ‘best interest of the child’ is highly subjective and undefined”, says Amba Salelkar, a lawyer with International Disability Alliance, a global umbrella organisation focused on rights for individuals with disabilities. “It can be seen either way — as enabling the capacity of disabled parents who love their children and would like to be a part of their upbringing, going beyond the societal stigma. Or to keep a child with able-bodied and fit parents to receive proper upbringing.”

Discriminatory Laws

“What constitutes the capacity to look after a child is subjective. But laws are often used to define and interpret this in ways that mirror the dominant societal discourse about a parent-child relationship, and more importantly, what it takes to be a ‘good mother’”, says Das.

A wide spectrum of laws limits the legal capacity, autonomy, and choice of women with disabilities, particularly those with intellectual and psycho-social disabilities.

For instance, under some marriage laws, including the Hindu Marriage Act and the Special Marriage Act, a person of unsound mind is either deemed “incapable of giving valid consent” or “unfit for marriage and procreation of children”. A family court can grant a divorce on the same grounds.

India is one of the first signatories to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2007 which mandates governments to accord equal rights and freedoms to people with disabilities.

“As a signatory India needs to implement all the provisions that would give disabled people equal rights in the national laws. Despite this, Indian family laws that govern marriage, adoption, guardianship are discriminatory and exclusionary against people with disabilities”, says Das.

The idea of ‘best interest of the child’ runs alongside the question of the agency of a woman with a disability to be a mother in legal jurisprudence. The question cropped up in 2009 in the Suchita Srivastava case (referred to as “Nari Niketan Case”), where a woman with an intellectual disability fell pregnant after being raped by the guards of a protection home in Chandigarh. The woman had refused to abort the child against the advice of her doctors. Apart from the violence of rape, the question under discussion was – can a woman with an intellectual disability choose to become a mother?

The Punjab and Haryana High court in its judgement noted that the woman had no idea of the “sexual act and its attendant emotions” or the “concept of marriage”. More specifically, the court noted that she was ignorant on the subject of “child-rearing”, especially “how to provide succour and sustenance to the child” before it ordered “in her best interest” to abort her child.

The Supreme Court, while overruling the decision of the Punjab and Haryana High Court order to terminate her pregnancy, took cognizance of the fact that the woman had expressed her eagerness to carry the pregnancy till its full term, in spite of the fact “she is unable to appreciate and understand the consequences of her own future and that of the child she is bearing.”

Though the Supreme Court’s decision settled the questions of law raised in this particular case admirably, some overarching questions remain unanswered — what does it mean for a disabled woman, especially intellectually disabled women, to provide consent on whether she wishes to be a mother?

For disabled mothers, especially those with intellectual and psychosocial disabilities, losing custody of children is an omnipresent fear. Under the older Guardian and Wards Act, “mental illness” had been used often to take away the rights of a mother to care for her child. In a 2008 case, the court gave custody of a young disabled child to the uncle because his mother “developed a mental illness” after the father’s death. The court order noted that “it is the principle that the state must care for those who cannot take care of themselves, such as minors who lack proper care and custody from their parents.”

The Juvenile Justice Act of 2015, which replaced the Guardian and Wards Act, also states that “a child of mentally retarded parents may be declared free for adoption by the child welfare committee, by following the procedure under this act.”

“The law is actively treating cases of intellectual disability differently. The Juvenile Justice Act talks of counselling and period of inquiry to check for the adoptive parents’ background, but bypasses them when the parent has an intellectual disability”, says Salelkar. “The law is creating different kinds of circumstances for intellectually disabled parents and is not considering the possibility that they could raise the child, if proper support is provided.”

Lack of state support

Disabled mothers often have no safety nets or financial support from the state. States like Kerala, Maharashtra and Karnataka have pension schemes to support parents or caregivers of persons with disabilities. But this does not encompass support to disabled mothers in raising their children. Women with disabilities need financial support in not only accessing caregiving assistance for their children which can be prohibitively expensive but also for disability-related expenses, such as medication, adaptive equipment, transportation and housing modifications. State-driven financial safety nets become even more imperative as 69% of the disabled population in India lives in rural areas according to the 2011 census with inadequate support and fewer resources.

“The social stigma about women with disabilities pervades through the legal and state institutions too. This means that the care and support that disabled mothers require is simply not there as the state does not see them “capable” of being a mother”, says Das.

Shampa Sengupta and Swagata Raha in their paper found that, for several disabled women raising a child without state support is difficult. While the Rights of Person With Disabilities (PWD) Act, 2016, makes a provision to support women with disabilities for livelihood and the upbringing of their children, it does not make it obligatory for the state to provide any assistance to disabled women who become mothers.

“There is no systematized policy or scheme that specifically looks at disabled mothers, largely because there are a lot of different ministries and departments involved”, says Rupsa Mallik, former director of Creating Resources For Empowerment in Action (CREA), a global feminist organisation working on human rights. “Maternal health and benefits fall under the ministry of health and family welfare, disability rights under the ministry of social justice and then there are other schemes under the women and child department ministry.”

Disability inclusion is absent even in a lot of schemes and policies related to maternal health. For instance, the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY), which provides conditional cash transfer to pregnant and lactating mothers for wage-loss during childbirth and initial months of motherhood, imposes conditionalities such as completing prenatal care and child immunisation in the first six months, to be able to access the benefits. Many of the spaces where these services can be accessed are themselves inaccessible for disabled mothers.

Western countries, like Canada, have nurturing assistants to help with childcare tasks. In Sweden, disabled people have the right to personal care, irrespective of their diagnosis. They can use personal care for whatever tasks they require support in, including child care.

“We have to rely on family and friends at times of distress because there is no state support,” says Harpriti Reddy, a deaf woman who is mother to a thirteen-year-old daughter.

Apart from caregiving services, support for disabled mothers also includes enabling them to participate meaningfully in their child’s life, such as making sign language interpreters available at parent-teacher meetings for deaf parents.

While acts like the Persons with Disability Act, 1995 have made provisions for employment for people with disabilities in the public sector, and organisations like National Handicapped Finance and Development Corporation give loans for persons with disabilities, the implementation remains tardy in both areas. There is no targeted support for disabled mothers, thereby, missing the intersection between disability and motherhood.

Disability rights advocate and lawyer Amba Salelkar, who lives with psychosocial disability, narrates her experience with financial anxiety during the early years of motherhood.

“Though I considered myself a veteran when it came to my mental health issues, I found myself completely taken by surprise when it came to postpartum depression and anxiety. I needed support, which I didn’t realize at the time, even to communicate. Additionally, I was pressured to work, because I was a freelancer, which meant that there was no maternity leave.”

Salelkar managed to tide over with some savings and financial support from her partner, who had to return to work soon after their son’s birth.

“The thought of having no income for nearly a year after my child’s birth was extremely distressing, especially since I was paying for a support person to help with the child and around the house.”

It is tougher for single mothers with disabilities to cope with the demands of parenting as policies and schemes are entirely absent to support them. Schemes, like the Indira Gandhi National Widow Pension Scheme, once again, miss out in including disabled mothers.

Many Ways of Being A Mother

“Parenting demands so many different kinds of ability that most of us start, at least, with some kind of deficit,” says Jeeja Ghosh.

But how much is too much? How do women with disabilities negotiate their role as mothers?

“I believe that my disability takes away this narrow misconception that there is a ‘normal’ way to be a mother ”, says Hera.

Hera, who finds it difficult to understand the notion of time and recognise her hunger signals, has created a unique schedule for her son’s meal. Before the pandemic, she would wake up at 4 AM and list down the tasks for the day revolving around her son’s daycare schedule. During the pandemic, when the daycare was closed and his routine was disturbed, Hera made a new schedule, which revolved around his nap time, relying on her alarm to remind her to prepare his meal. Sometimes, she also has to rely on others, especially when she has missed comprehending time.

Ghosh’s disability requires her to seek assistance to perform some of the physical tasks of parenting, like picking up her daughter when she falls.

“My child and I would need to live and work with others, and in so doing, develop a close circle of caregiving”, says Ghosh “But if it is acceptable for a non-disabled mother to hire a nanny to juggle parenting, career and domestic responsibilities, why is this assumed to be taboo for me?”

For Salelkar and her young son who does not understand her disability fully yet, it is a constant learning process with open communication.

“There are certain things that are sensory overloads for me that need to be explained. At times when I have my own meltdowns, I need to explain to him that it is not his fault. It is a continuous process of learning for both of us, but it has made me respond to his sensory overloads and meltdowns better, in a more empathetic manner”, she says.

Harpriti Reddy’s thirteen-year-old daughter, on the other hand, learned sign language when she was a child. She now acts as an interpreter between her deaf parents and non-disabled people.

Disabled mothers like Jeeja Ghosh, Hera, Amba Salelkar and Harpriti Reddy have to constantly negotiate a culture that allows them no point of reference or validation of their experiences but shames them for choosing to be a mother. Yet, their experiences show that there are many ways of being a mother and raising a healthy child.

“Motherhood is bound to have its own share of challenges and I am aware of that. But having Hiya (her daughter) with us has changed our lives”, says Ghosh. “My primary concern is to bring her up as a person who is upright in her decisions and sensitive to our challenges.”

“Motherhood is very hard for me. But no one loves my child like I do. And my family knows that. Everyone knows that ”, says Hera.

(*the name of the person is hidden to protect her identity)

[This is the third report on the series on violence and exclusion faced by women and trans persons with disabilities in India as part of the Spotlight Media fellowship. The fellowship is a collaboration between Rising Flame and BehanBox. You can read the previous report here and here.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.