While SC/ST Budget Allocations Rise Marginally, Caste Realities Remains Unaddressed

Even as SC/ST allocations nominally rise in the Union Budget 2026-27, most funds remain non-targeted, underutilised, and inaccessible to the communities they claim to support

Even as climate change, geopolitics, platformisation of labour and the AI boom exacerbate the existing vulnerabilities of India’s most marginalised social groups, the Union Budget 2026-27 has slashed allocations for schemes that specifically target their needs, show analyses done by multiple civil society organisations.

For Deepa* 54, a waste picker from PMGP Colony in Mumbai, the Budget and the buzz around it mean little. She says it means nothing for her or her family who live and work in a state of extreme precarity. It certainly meant very little when she lost her son last year.

“He suffocated to death inside a septic tank that the BMC hired him to clean. No one came to help him. The contractor did nothing, he offered us no compensation,” she said. “And the BMC has just left us to rot in some corner of Mumbai.”

Like Deepa, several Dalit and NT-DNT residents of M-East Ward, a largely working-class area of eastern Mumbai, have lost at least one family member to the hazards of manual scavenging. Workers are paid just Rs 100-200 per day for this work, and without safety gear, oxygen cylinders, or ambulances on standby.

The corporation sub-contracts this work to private companies to deflect accountability, as officially, manual scavenging has been banned in India for 13 years now. But between 1993 and June 2025, the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis recorded 1,313 deaths related to the occupation.

This neglect becomes apparent in policy changes over the last few years as well as Budget allocations. Till three years ago, the Scheme for Rehabilitation of Manual Scavengers (SRMS), which was allocated Rs 70 crore in 2022-23, mandated compensation, cash assistance, loans, upskilling and rehabilitation for manual scavengers with financial support from the National Safai Karamcharis Finance and Development Corporation (NSKFDC). But then, in 2023, the SRMS was replaced by a new scheme that reduces the issue of sanitation to mere mechanisation without mention of rehabilitation or manual scavenging: the National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem (NAMASTE).

Budget 2026-27 has allocated Rs 110 crore to the NAMASTE scheme for bureaucratic strengthening and mechanisation, while the NSKFDC gets just Rs 0.01 crore.

This pattern is not limited to manual scavenging. As our reporting has shown, poor budgetary allocations and underutilisation of funds are among the reasons that have eroded safeguards and rights for vulnerable groups across the country.

“Budget allocations are important because they can be read as formal acknowledgements that SC/ST communities require targeted public investment to correct historic injustices. Yet, year on year, we see that SC/ST budgets are relegated to the margins,” said Mohsina Akhter, a member of the Delhi-NCR based Dalit Adivasi Shakti Adhikar Manch (DASAM). “You cannot eradicate manual scavenging and other hazardous caste-bound work by allocating such a small and untargeted budget, without any implementation plan in place.”

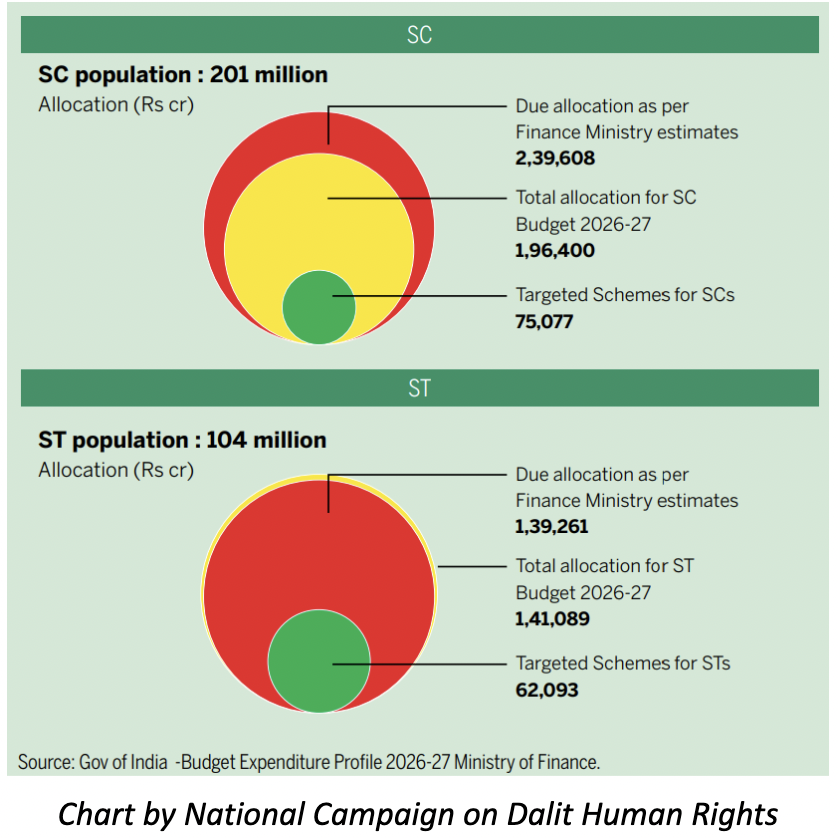

In FY 2026-27, Budget allocations for the welfare of Scheduled Castes increased by 16.6% from last year’s allocations and that of Scheduled Tribes saw an increase of 9.2%. Yet, these allocations are disproportionate to the population of the communities. NITI Aayog suggested that funds for SCs should make up 14.6% of the total eligible central schemes funding, while in reality, they remain at just 11.8%.

Furthermore, as we detail later, an analysis by the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR) shows that only 4.5% of the SC budget and 3.7% of the ST budget are clearly targeted towards schemes directly benefitting SC/ST communities, resulting in massive funding gaps.

“Sometimes large allocations look great on paper, but when you look on the ground, you realise the schemes are not reaching people,” said Beena Pallical, general secretary of the NCDHR. “Throughout the finance minister’s Budget speech, she only mentions industrialisation, road work, infrastructure, and so on. Where are the people?”

There has also been a notable shift in the language of allocations — from ‘rights and rehabilitation’ to ‘welfare and charity’. We draw on multiple analyses of the SC and ST budgets to examine what this shift has meant for marginalised workers on the ground.

Intent Remains On Paper

Designated SC and ST budget allocations first appeared in the 1980s through the Scheduled Caste Sub-Plan and the Tribal Sub-Plan, aiming to address poverty and unemployment, and expand access to social rights such as education, healthcare, housing, and water. Each ministry’s budget for SC/ST-specific plans was to be proportionate to the group’s population share.

On paper, the plan appears effective. But a review of SC/ST budget allocation and implementation over the past five financial years reveals four recurring issues: chronic under-allocation relative to population share; diversion of funds into general schemes; significant underutilisation; and weak accountability and monitoring. Civil society has long demanded legislation to mandate sub-plan allocations and strengthen State accountability, as Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, Uttarakhand and Rajasthan have done.

Analyses have also shown that the Union government has ended up blurring boundaries between targeted and general schemes and masking underutilisation. In 2018, new guidelines issued by the NITI Aayog restructured and renamed the sub-plans as “Development Action Plan for Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes (DAPSC/DAPST)”. Earlier, each ministry would make targetted allocations to develop programmes and schemes for the benefit of SC/ST. Under the new format, SC/ST funds are allocated within individual schemes regardless of whether the schemes are relevant, turning allocation into an end in itself.

“With schemes being dropped and merged over the last few years, the new DAPSC/DAPCT system makes it difficult to track allocations between the lines. There should be clear guidelines that highlight if and how schemes are targeted towards SC and ST communities,” said Beena.

“This weakens the ability of these communities to demand their legal share, as they now need to prove they have a right to welfare schemes,” said Mohsina. “Informal and vulnerable workers like manual scavengers are often unable to do this due to a lack of documentation and clear definitions.”

Non-targetted Schemes Dominate

While both SC and ST budgets show nominal increases in total allocations this year, analyses by Adivasi Adhikar Rashtriya Manch (AARM) and NCDHR indicate that the funding has little direct link to community development. This is largely because it is aimed primarily at a large number of general and non-targeted schemes – only 33 of the 259 schemes for SC and 47 of the 294 schemes for ST are targeted.

Targeted schemes – such as the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY), Eklavya Model Residential Schools, Post Matric Scholarship for SCs/ STs, VB-G RAM G, and PM Vanbandhu Kalyan Yojna – directly address the needs of the SC/ST communities. These have only received a total of Rs 1,37,170 crore – just 6.8% of the total of Rs 20,05,436 crore allocated for SC and ST schemes.

On the other hand, non-targeted and general schemes that have little meaning for SC/ST communities – the Exploration of Coal and Lignite, Road Works, Compensation to Telecom Service Providers, Semiconductor Manufacturing, and Infrastructure and Loan Support to IITs and NITs for instance – have been allocated staggering amounts of money (Rs 18,68,266 crore) under the SC/ST budgets.

A second, persistent issue faced by schemes is the underutilisation of funds. Only around 80% of SC/ST funds have been utilised each year since 2019, as per data from the Ministry of Finance’s Union Budget reports and the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG). In FY 2019-20, 20% of SC funds and 11% of ST funds were unutilised, while in 2024-25, this dropped to 25% and 15% respectively.

Sectors That Lost

AARM and NCDHR’s scheme-wise analyses reflect these allocation, utilisation, and failures in FY 2026-27 across key sectors:

Caste-Based Atrocities: Despite rising caste-based atrocities and low conviction rates, FY’26-27 allocations for implementation of the Civil Rights Act (1955) and Prevention of Atrocities Act (1989) remain stagnant at Rs 550 crore – insufficient for victim relief, legal support, and institutional strengthening. This under-allocation comes despite the fact that in 2023, schemes offering additional monetary relief for victims — such as the Dr Ambedkar National Relief Scheme and the Dr Ambedkar Scheme for Social Integration through Inter-Caste Marriages — were merged within central schemes and additional allocations were discontinued.

Education: In FY ’26-27, allocations for post matric scholarships have increased over last year: from Rs 5900 crore to Rs 6360 crore for SC students and Rs 2462.68 crore to Rs. 3176.48 crore for ST students. Similarly, allocations for the UGC and Central Universities have also increased. However, the budget clubs general infrastructure and administrative schemes under SC/ST allocations and includes no monetary allocations to address rising caste discrimination on educational campuses. While funds for Eklavya schools, intended for Adivasi students, have received Rs 7200 crores this year, they have faced repeated underutilisation in past years, with many schools shut down or yet to be constructed.

Gender-Based Crime: While there has been an alarming rise in crimes against SC and ST women, only Rs 550 crore has been allocated in FY’26-27 under the SC budget for implementing both the PCR Act, 1955 and the POA Act, 1989, with no allocation at all under the ST budget. Our reporting has shown that Adivasi survivors already face several barriers like opaque and exclusionary systems in accessing justice. Further, given the scale of systemic gaps in addressing gender-based violence against Dalit and NT-DNT women, even the Rs 550 crore allocation seems inadequate.

Girls Hostels: Earlier promises to open one girls’ hostel in every district for SC and ST girls are unclear, with no budget being allocated to this scheme this year (2026-27). Hostels often serve as crucial spaces of safety, stability, and support, especially in cities that are already hostile.

Healthcare: India’s public healthcare system remains underfunded, understaffed, urban-centric, and inaccessible for marginalised groups, with government health spending still below 1.3% of the total GDP. Rural health centres continue to face severe staff shortages, while frontline workers – ASHA and Anganwadi workers, often Dalit and Adivasi themselves – remain overworked and underpaid. In FY 2026–27, SC/ST budget allocations for the National Health Programme, National Urban Health Mission, and Ayushman Bharat–Pradhan Mantri Jan Aarogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY) remain largely stagnant, with little clarity on what these SC/ST-specific fund allocations practically mean. Meanwhile SC/ST funding for affordable medicines under the Jan Aushadhi Scheme has reduced by nearly 50% and Tertiary Healthcare – highly specialised and advanced medical care for illnesses like cancer and drug addiction – has received no allocations despite disproportionate impacts on women from marginalised communities.

Jal Jeevan Mission: While the SC/ST budget allocation has nearly doubled from Rs 12,800 crore last year to Rs 21,654.40 crore in FY’26-27, “the scheme does not include a plan to address the specific needs and issues of SC/ST groups,” said Beena. Our previous reporting shows how this lack of planning has left PVTG and Dalit women across Maharashtra’s hill districts without clean water.

Occupational Health and Safety: Across the SC/ST budget, allocations to address occupational health and safety for marginalised women in hazardous informal work remain absent: including sanitation, construction, textiles, beedi rolling, sugarcane harvesting, and stone quarries.

The budget also continues to offer little clarity or support for transgender communities, care workers, and the elimination of bonded labour, and allocations for gig workers remain scarce.

The NCDHR, AARM and DASAM put forth a series of recommendations to address gaps in the SC/ST budget. These include: clearly legislating SC/ST budget allocations to reduce non-targeted funding, properly allocating funds for scheme implementation, publicly tracking fund disbursement more frequently and transparently, and allocating funds on priority to completely eradicate caste-based occupations like manual scavenging – through rehabilitation, compensation, legal and criminal accountability, social security, and the mechanisation of sanitation work.

Specific scheme wise recommendations can be found in NCDHR’s report.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.