How Jal Jeevan Mission Left Women In Maharashtra’s Hill Districts High And Dry

The taps and pipelines meant to carry water to the homes of hill-dwelling communities of the state have either not been installed or have no water supply. Women trudge miles and undertake risks to collect water

- Priyanka Tupe

Among the women crowded around the public well in Haripada, a hilly village in Maharashtra’s Palghar district, is Urmila, 20. She is eight months pregnant, yet she has to do a 2-km trudge four times a day under the scorching April sun to fetch water for her family.

The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) that should have brought water to her home has failed its promise, Har Ghar Jal (water in every home), in her village. Launched in 2019, it aimed to provide all rural homes with safe and adequate drinking water through household tap connections by this year.

There is only one source of potable water in this village that lies in Jawhar taluka in Palghar district, just 100 km from Mumbai – the public well whose water level is dipping by the day. The water crisis is so acute that women like Urmila are willing to risk their lives for it.

Urmila, like all the other women, stands at the edge of the well with several pots to fill. What if she slips and falls, we ask. “We are used to this. What do we do otherwise?” she says.

It is 3pm and we find young children ferrying water from the well: Shreya, 6, for instance, who has walked barefoot from her home. We saw these scenes across at least half a dozens of other villages such in Wada and Jawhar talukas of Palghar – Kati, Bandharepada, Budhawali, Vinval, Bothadpada, Hiradpada among them.

Ananta Patil, the sarpanch of Budhavali village in Wada says he has to order water tankers into the Katkari basti higher up on the hill in his village. The Katkaris are counted among the particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs) that live in extreme poverty and deprivation and they live mostly in Palghar and Raigad districts of Maharashtra.

“Other villagers at least get water from their neighbours who have borewells. Katkaris stay on the hill where there is no source of water,” he says. In areas that are placed high on hills, the water levels in public wells has gone down considerably.

The tribal women we spoke to in Hiradpada know nothing about the Jal Jeevan Mission or its promise of clean and easy water access. Women of Bothadpada complained that their water needs have been ignored for a decade since their village was acquired for a dam project. “You will be displaced anyway, why should you be given a water connection?” That is the answer of the sarpanch and other government officials when the villagers demand water, says Sunita Morgha.

All the women we met in Wada and Jawhar talukas have no choice but use its contaminated ponds – full of mines being blasted for stones and sand – to wash clothes.

These are not just Palghar’s troubles; during our recent travels for election reportage we found that women from at least eight villages of Akola, Amravati, Yavtmal have to carry water from wells and public taps.

District-wise data from the Jal Jeevan Mission dashboard show that in Palghar, 66.83% of households have water taps – 2.96 lakh of 4.44 lakh homes – which means there are 1.47 lakh households that have yet to receive functional tap water connection. On average, 85% of households in Maharashtra have tap water connections. Some district variations exist: for instance, districts such as Gondia (74.89%), Thane (70.35%), Beed (69.99%), Nandurbar (52%), an aspirational district, have lower than average tap water connections.

There are 19.3 crore rural households in India and of them 14.6 crore (75.97%) have tap water connections, as on April 14, 2024, per official data.

The JJM portal also says here that there are five impact studies on its impact on health, but all five mention the ‘potential (estimated)’ impact. “These reports are a modelling study where multiple factors have been ‘assumed’ to produce a number which could be the potential impact of the Jal Jeevan Mission,” says a medical expert who wishes to remain anonymous.

Backbreaking Work

Sakarabai Kengar, from Dhangarwadi village in Yavatmal, ferries water from a public tap 500 metres from her home at least 6-7 times a day, carrying at least three vessels at a time. Barely into her 30s she is already dealing with joint pain. “This is backbreaking work and we have to do this for our family. I also work the whole day as a daily wager and handle other household chores so I get late sometimes for my evening adult literacy classes. If I had a doorstep tap and water supply, I would have found time to study,” said Kengar.

The other women we interviewed in Palghar district raised similar complaints. We didn’t find a single village which has taps and a functional water supply in the 13 villages we visited from Akola, Amravati, Yawatmal and Palghar.

The situation is the worst in the Trimbakeshwar and Igatapuri talukas of Nashik, says Mayuri Dhumal, a Nashik-based researcher who works on water, sanitation and gender. Tankers provide water to hundreds of villages here. And over 900 villages need water by tankers in Marathwada region.

Dhumal says women of the district’s villages have to carry an average 1800 km for water every year, carrying an average weight of 22,000 kg or 22 tonnes per year on their heads.

“The Jal Jeevan Mission data for three villages in Nashik – Hirdi, Dhumodi and Bramhanwada of Trimbakeshwar region – show that these villages have 100% household tap connections and a regular, functional water supply. This is not true and women are fetching and ferrying water from common wells. Taps have been installed in Dhumodi village but there is no water supply yet,” said Dhumal.

Her research also revealed that many households in Hirdi and Dhumodi villages who have been marked as beneficiaries on government records, had no idea they were supposed to have a tap connection on their name.

“Private/individual water sources like wells, borewells, common water sources like check dams, river streams are also being passed off as tap water connections under the scheme by implementing agencies. This is misleading. To reduce the gendered labour that goes into water acquisition in homes, women need water at their doorsteps, not wells, river streams and check dams in the villages,” says Dhumal.

Dry Taps And Pipelines

In March, when we traversed 13 villages of Akola, Amravati, Yavatmal and Palghar districts we found that only household taps and pipelines had been installed but there was no water supply. The installation of water storage tanks is still in progress.

In Palghar villages, the Shramjeevi Sanghatana which works on people’s participation, awareness and advocacy issues around the water mission, held week-long agitations to protest the shoddy installation of pipes. These should be installed at least 3-feet deep into the ground for sustainability but the engineers are installing them on the surface, said Vivek Pandit, president of the Sanghatana. Women from Jawhar, Mokhada, wada blocks of Palghar district participated in large numbers in this agitation in the first week of April with a utensil in one hand and a wooden stick/ bamboo in the other hand. (The bamboo was used by the agitators to dig the ground around pipelines to check whether they were properly installed underground.)

In all four districts, we found incomplete installations of taps, pipelines, and storage tanks and according to the people we spoke to, even this progress was made only in the last four months.

“There is no supply of water in our homes and the pipelines are now being installed, in the months leading to the Lok Sabha elections,” Bharat Bharde, gram panchayat member of Tiwasa village in Akola, told Behanbox.

Keeping Wells Clean Is Women’s Chore

The mission has promised 55 litres of clean water daily to every individual. All the public institutions in rural areas including Anganwadis and Adivasi Ashramshalas are to be provided water through taps. But there is no domestic water supply or centralised water purification mechanisms in the 14 villages we visited. The women carry water home from wells and public taps and then boil it and filter it through cotton cloth or they use potassium alum to purify it.

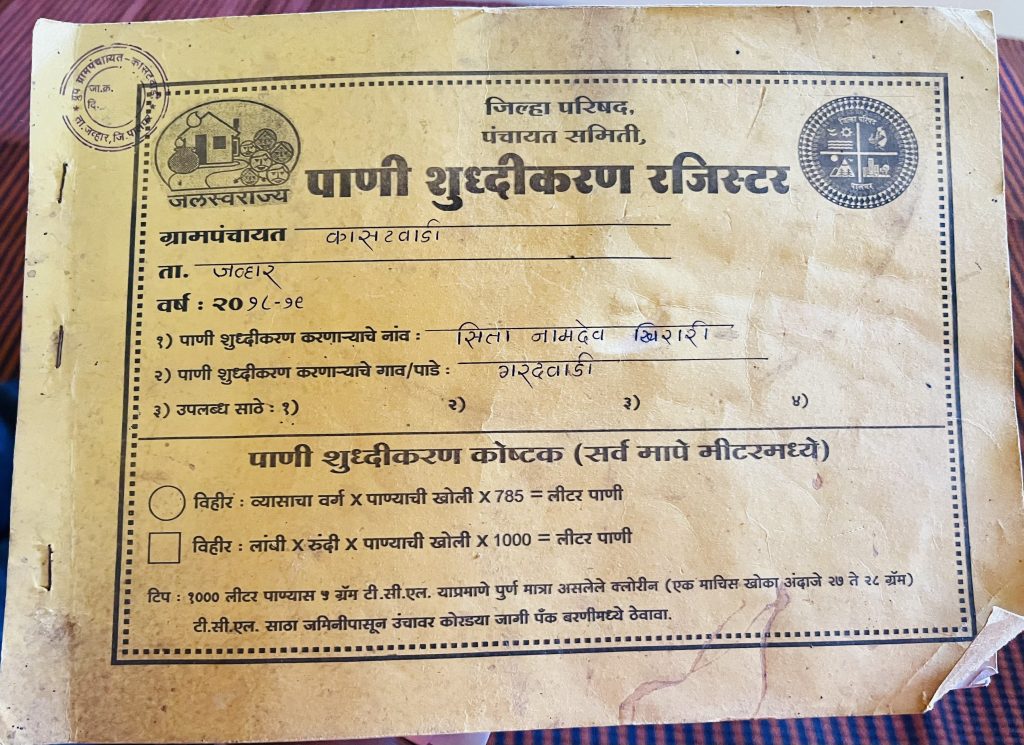

In districts like Palghar, pada (hamlet) sevikas are appointed by zilla parishads with the help of gram panchayats to ensure the daily purification of the water in the public wells. This involves mixing calcium hypochlorite (bleaching powder) in the water.

Seeta Khirari of Garadwadi pada of Kasatwadi village in Jawhar block has been working a pada sevika for 25 years. “I can’t leave the village, and not more than a day because of this huge responsibility. We are provided with 25-kg sacks of bleaching powder at the beginning of the year. I also have to ensure it is kept out of children’s reach,” says Khirari.

Khirari receives Rs 300 as a monthly honorarium for this work and this sum has not changed in 25 years. The only change is that in the last 10 years the payment has become online, but is delayed by 3-4 months, she told Behenbox.

This work is done entirely by women and in monsoon, when contamination increases, they have to also distribute bottles of sodium hypochlorite solution to each household. Women in households are advised to mix two drops of the solution to every utensil holding water, approximately 20 litres of water. This is to prevent diseases like cholera and diarrhoea and if a child still falls sick the onus is placed entirely on the mother, women told us.

As a precautionary measure to prevent the outbreak of diseases caused by contaminated water, primary health centres conduct monthly assessment of drinking water sources in every village and discuss solutions to problems with gram panchayats. If water contamination is detected by the PHC, sarpanches are asked to stop villagers from using the water till it is decontaminated. PHCs are also expected to maintain the records of water samples taken and ensuring action. But in Hiradpada village we sifted through the PHC reports and found that water was contaminated about half a dozen times between 2019 and 2021 but there were no records for the remaining years.

Adivasi School-Hostels Buy Half The Water

At the two state-run Adivasi Ashramshalas (residential schools) in Vinval and Budhwali in Palghar there is no water available on tap under the Jal Jeevan Mission. Both get half their water supply from wells and through the pipelines, and water storage tanks provided to them under the old Jalswarajya Project, a demand-driven water rural supply project in Maharashtra launched in 2003. They complement this with water bought from tankers.

The water tanks and pipelines at Vinval Ashramshala are at least a decade old and in dire need of maintenance. The Vinval ashramshala has nearly 1400 students.

“Summer is no exception, our school management buys water tankers throughout the year. Buying 15,000 to 20,000 litres of water everyday costs Rs 70-80,000 a month which gets reimbursed by the tribal department. The government provides us with water storage facilities, pipelines and tanks but there is no water supply,” says a parent and member of the school management committee who wishes to remain anonymous.

There is a central kitchen in this school premises that provides freshly cooked mid-day meals to 27 tribal schools in Palghar, lacks adequate water supply facility in the premises and School management has to buy water tankers everyday which costs Rs. 5 to 5.5 lakh a month, we found.

There is no running water supply in the toilets of both the institutions, leading to sanitation issues. The toilet at the Vinval Ashramshala, with no water and in a filthy state, was unusable. For the adolescent girls of the Ashramshalas, toilet use during school hours is a challenge. “We don’t use the washroom unless we simply have to during the 6 hours of school. We prefer to use the hostel toilets even during classes,” said a girl. The hostel is 500 metres from the school building.

Kalyani Pawar, a Palghar-based menstrual health activist, says that this clean water crisis forces women to drink less water and also impacts their menstrual health. In her menstrual awareness sessions, she has found that adolescent girls in schools are particularly affected by poor access to water.

We met dozens of the young girls at the Vinval hostel carrying buckets of water drawn from the taps attached to a water storage tank outside because there was no water in the common bathrooms. “We do all our laundry here at the tap only. Our weekend looks like this,” says one of the girl students we met at the hostel.

We also visited two Anganwadis in Wada taluka, where Anganwadi workers and helpers have to store the water in the absence of tap connection and water supply.

‘Skewed Distribution, Not Benefiting The Poor’

Parineeta Dandekar, researcher and associate coordinator at the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People, says poor water access for the state’s disadvantaged populations is not a question of shortage but of unequal distribution of water.

“Palghar gets 2000-3000 mm of rainfall per year compared to 600-700 mm in the Western Ghats. Yet, women in Palghar risk their lives to organise drinking water. One reason for this [shortage] is soil erosion and because all the big dams built in this region provide water to the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority. Local tribals have all the rights to the natural resources in their area but it’s not legally ensured in reality,” she says.

Tansa, Bhatasa, Upper Vaitarna, Middle Vaitarna, Lower Vaitrana dams and Tulasi, Vihar lakes built in Thane and Palghar districts provide water to Mumbai and suburbs and people in Palghar face water scarcity besides living near dams.

This lack of water for individual consumption and irrigation schemes results in increasing poverty. It also contributes to malnutrition caused by lack of diversity in agricultural produce, and high maternal and infant mortality figures, Dandekar points out.

This report by South Asia Network Dams, Rivers and People cites the pre-feasibility report of the Damngana-Vaitrana-Godavari interlinking project, most of the water in the Mokhada-Palghar region will go to cater to the industrial needs of Sinnar, Nashik and water requirements of the Delhi-Mumbai industrial corridor. The needs of Palghar are nowhere on its agenda.

“Jal Jeevan mission emphasises on infrastructure, but without ensuring the management of groundwater properly , there won’t be enough water available in water sources. Water supply to industries and the extreme extraction of water by industries affect groundwater availability. To ensure the just and equitable water access to everyone, the effective implementation of the Maharashtra Groundwater Regulation for Drinking Water Purposes Act 1993 is necessary. Jal Jeevan mission can’t be successful without it.” says an expert.

This Act empowers the authorities like district collectors to regulate the management of groundwater by taking control of the availability of water in the water resources in the district. The district collector can restrict or prohibit the use of such water resources and authorities like collectors are expected to prioritise adequate supply of drinking water over any other usage of groundwater.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.