[Readmelater]

Sleep And Night Time Economy In A Street Vendor Neighbourhood

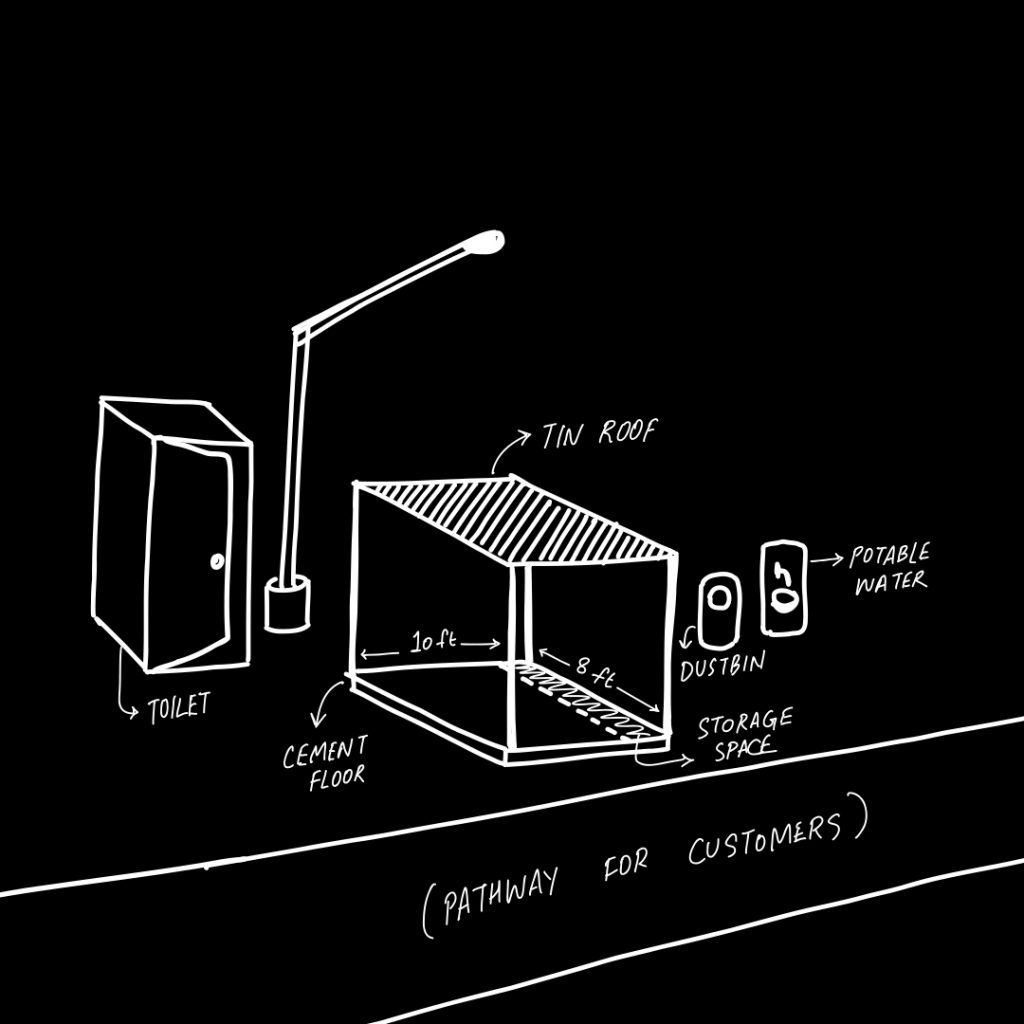

What are the peculiarities of sleep and rest in the life of a female street vendor who works in a market that opens before dawn? Can alternate ideas of urban planning help reimagine her life, ease her anxieties? We return to Delhi’s Raghubir N

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.