Vending Law Ineffective, Raghubir Nagar’s Pheriwalis Reimagine Safe Work Spaces

In this, the second in the series ‘Placing Work, Mapping Places’, we detail the struggles of Raghubir Nagar’s pheriwalis in dealing with street and State violence. We ask them to reimagine their workspaces as safer, gender-friendly and mor

“I started vending on the streets behind Lal Qila when I was eight, along with my mother. I remember the brutal violence we faced during police raids. Once a tall policeman tried to grab my mother’s gathri, but she tightly held on. In anger, he slapped her hard… twice. Even now, when I go to Meena Bazaar, my legs tremble at the memory,” says Sona ben, 42, a pheriwaali and vendor from Raghubir Nagar.

The pheriwali is a unique presence on our city streets, a stack of utensils on her head and a gathri (bundle) of clothes slung on her arm as she does periodic rounds (pheri) of colonies and homes, as we detailed in the first part of this series. Women like Sona ben once used to be familiar figures at the doorstep of urban households,negotiating a barter – old clothes for new utensils. These clothes are then recycled with the help of tailors and embroiderers, and sold once they are made attractive and reusable. In Delhi, the homes and markets of pheriwalis lie in Raghubir Nagar in west Delhi.

But as Sona ben’s experience shows, it is a hard life, vulnerable to violence from both the State and those they encounter on the streets which they inhabit as residents, buyers and sellers. The one law that could have shielded them from this brutality, the Street Vending Act of 2014, is ineffective, as we show later.

The pheriwali’s identity is gradually disappearing from Delhi’s urban landscape as their work dwindles in the face of changing socio-economic factors. Typically, a significant portion of a street vendor’s day is spent outside their homes, navigating the public realm and servicing networks of supply chains and diverse consumer base at affordable rates. Safe workspaces for them mean safe streets.

Our work documenting the life of Raghubir Nagar’s pheriwalis shows us that the act of street vending in Indian cities is a daily act of turning public spaces into places of work. We call this placemaking and it is a familiar sight across our cities. From a banta wala quenching your summer thirst with a soda to a samosa wala adding joy to monsoon teatime, these encounters are permanent fixtures of our city life and cityscape.

A street vendor setting up a shop on streets, pavements, roadside curbs, or under a metro station is a deliberate act of reclaiming public spaces. For decades, street vendors have contributed to the urban informal economy without legitimacy, brought vibrancy to the streets, acted as eyes on the streets to make cities safer, and negotiated for space to earn a livelihood every day.

But violence makes the life of hawkers arduous and renders their place of work undignified. Then there are other obstacles — restrictions on vending in certain areas, unexpected disasters like the pandemic that led to a ban on weekly markets during lockdowns, the lack of legitimacy and uncertainty associated with their work, and poor access to public transport and basic infrastructure like toilets and safe drinking water. All these have eroded the place of pheriwalis and many other vendors in the city.

The everyday act of place-making then becomes a brave retort to the threats posed to their livelihoods. It offers a way to reclaim their position in the city through a complex ecosystem within which various players coexist and perform an unrelenting contest for space.

Just as a woman walking at night through a dimly lit street needs basic street lighting to feel comfortable and secure, disabled people have multi-sensorial infrastructural needs to access streets, children and the elderly need more play and recreational spaces and trans people need more inclusive, visiblised spaces to belong, pheriwalis needs dignified places to work to earn a livelihood.

Lack of legal legitimacy

The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation) Act of 2014 became an exemplar in policy and law-making, granting Street Vendor rights to vend and work in pre-demarcated zones in a city. It resulted from a long-standing fight by the Civil Society and Street Vendor Unions to ensure protection against everyday harassment and displacements by the State.

However, almost a decade later, our interviews with the female vendors of Raghubir Nagar showed that the act, once lauded for its protecting the livelihoods of millions, lacks on-ground implementation and awareness building for vendor groups regarding their renewed rights and responsibilities.

Usha ben, a vendor, is also a community leader with SEWA, the self-employed women’s association which has a huge presence in the area. She remembers feeling overjoyed with a sense of victory when a law safeguarding the rights of vendors was passed. But, she is also acutely aware of how difficult it is to build a collective understanding and use of the law for vendor groups conditioned to live a life of precarity.

India has an estimated 10 million street vendors with no reliable data on street vending in the public domain. The street vendor act could have shielded the trade from random State action, investing vendors with legal rights to work in public spaces. But we found that only a handful of the women in Raghubir Nagar know about the act and how it benefits their quality of work and legitimises their place in the city.

According to the Parliamentary Standing Committee’s findings in 2021, not even a third of India’s 4,372 towns have street vending plans.

Street vending act provisions

The Street Vendor Act (SVA, 2014) prohibits evictions and relocations without compliance with proper processes. The most fundamental and primary of these is the vendor certificate, a vendor’s biggest weapon against forced eviction. A vendor with this certificate has to be given 30 days of notice before being removed from a vending spot. In case an eviction is carried out, an alternative spot has to be provided for relocation of the vendor’s business. If there is no functional Town Vending Committee (the TVC acts like a street government because all matters relating to it the street, from maintenance to redevelopment, is handled by it), eviction cannot occur without a survey being conducted of the vendors and provision of vending certificates to all surveyed.

Reclaiming of confiscated goods is possible using video and photo documentation of the material taken away during eviction. There should be a demand for written documentation of the total goods getting seized, and it’s important to enquire about the law on the spot when the eviction is being carried out. The authorities must return the goods on the same day if they are perishable and within two days if they are not. It is important to keep proof of identification if the vendor does not have a vending certificate.

These provisions have yet to be fully effective in protecting street vendors. The pandemic led to implementation delays and the vending community, often called “encroachers”, is being threatened with eviction as the Capital is being beautified for the G20 summit 2023.

The TVCs are responsible for issuing vending certificates and town vending plans. However, according to Raghubir Nagar vendors, the surveys conducted to issue vending certificates paused during the lockdown, and the process regained momentum only last year. They are waiting to hear back from the TVCs on the certificates. With a broken thread of information, vendor groups do not feel unhopeful about any positive change.

When informal work is not recognised as legitimate, workers’ contributions are often undervalued and excluded from “formal” spheres of planning and policy. Let’s further look at Raghubir Nagar’s example, where place-making was observed and documented by the women we engaged with during Aao, Jagah Banaye!

Raghubir Nagar’s Case

With the law currently ineffective, how can vending spaces be made more productive and attractive? Through a process of placemaking, we found in our interactions with Raghubir Nagars’ vendors.

Placemaking can be as simple as replacing an overflowing garbage dump with a flagpole. A derelict space transforms into a clean, walkable and safe space through a unanimity of opinions. We suggest below an example of a low-resource, quick and disruptive approach to reclaiming space by changing people’s attitudes toward littering.

There is no placemaking without people and their applied ingenuity. In the case of Ghode Waali Mandi–Raghubir Nagar’s daily market for second-hand clothes, without people and their daily activities of vending, gathering and earning a livelihood, the mandi becomes a non-space between 11 am and 3 am. It can instead be a permanent, vibrant and thriving hub for the local informal economy that is special to Raghubir Nagar, the women suggested.

A place’s transformation must deploy people’s perceptions and imaginations and vice versa. Here is an example of a City Sabha project inspired by a grassroots movement that began in San Francisco to make private parking spaces more social, accessible places. We worked on a pop-up intervention in a marketplace in south Delhi’s Chittaranjan Park to help local vendors find more space to service crowds during the pop-up.

The following is an illustrative grassroots example of place-making by the women of Raghubir Nagar, whose priority needs include: improved places of work, more efficient laws, less violence (from men and the state), and increased safety.

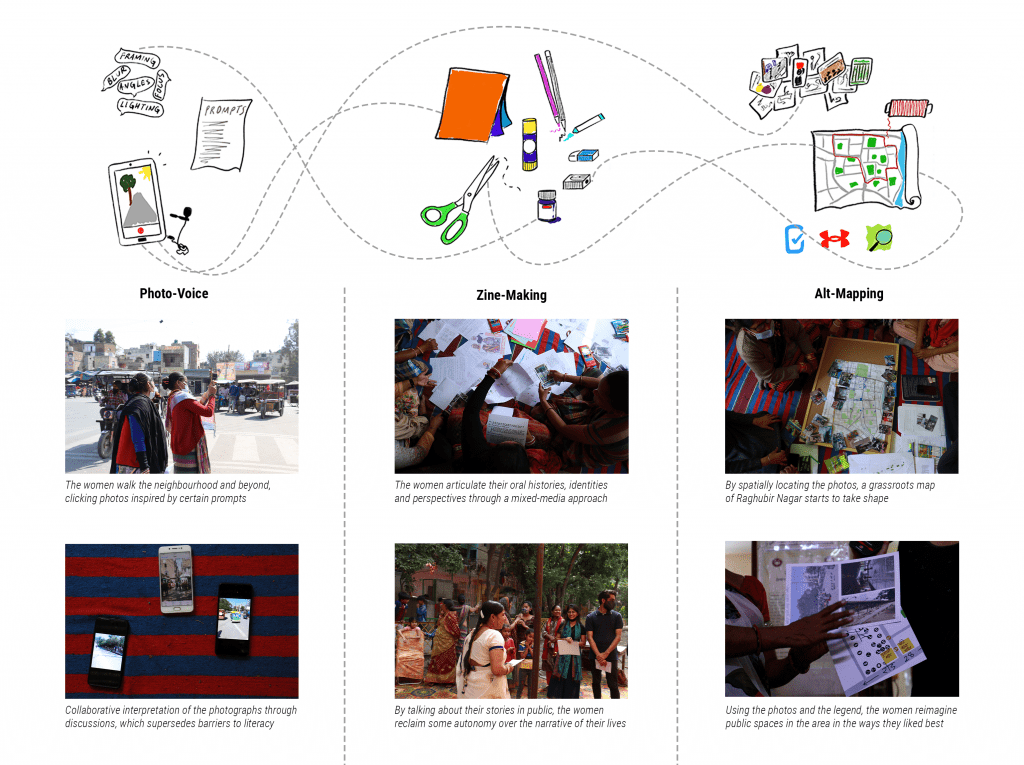

Through an iterative and experimental process, we co-created a methodology to unearth the multiple layers of their lives and livelihoods, using tools that resonated the most: photographs, alternative mapping and zine making.

We asked the women to plot their work and mobility patterns on a large-sized paper map of the neighbourhood. But it was a challenging task for most: they needed help visualising their surroundings on paper and making sense of directions. But a transformation occurred when we introduced the participatory tool of Photo-Voice, an app which combines two basic smartphone features, clicking a photo and recording an audio. The women became free, expressive, and eager to participate in the mapping process. Adding voice to the mix bridged the barriers to literacy and added another dimension to the photos.

Armed with their phones and a new-found agency, the women walked the neighbourhood and beyond, clicking photos of people, places, and nooks. They captured their daily lives, struggles and joys in these images. Instead of relying on outsiders to document the community, residents could take control of the narrative and share their own stories.

The photos fuelled conversations about spaces in the community, and the women perceived these spaces. They articulated personal stories about travelling to different neighbourhoods for work, navigating public spaces and transport options in the city, and cases of violence by men and the State (the police, MCD, and gatekeepers of privately-owned public places). Using the photos, they also voiced their issues with the existing spaces and demands for improvement.

A few months later, we collected a rich repository of photographs reflecting the women’s lives and the places they inhabit. Pinning the photos accruing to their locations, a grassroots map of Raghubir Nagar started to take shape.

Simultaneously, a legend was developed: it started with the women drawing their own symbols and giving them names. The symbols were digitised and re-designed over multiple rounds of feedback. The legend is hyper-local and captures the diversity of activities unique to the community. The women used it to articulate their present needs and future reimaginations of places in Raghubir Nagar.

The community-generated map of Raghubir Nagar captures the various ways public spaces are used. The parks in Raghubir Nagar function as places for leisure activities. They are also used to store cloth gathris, do domestic chores, and for local competitions. Similarly, streets are used for informal vending and temporary vegetable markets.

This map helps identify activities under the ambit of planning, such as vending, vegetable mandis, and informal spaces and modify the layouts to allocate slots for them.

Using the photos and the legend, the women reimagined public spaces in the neighbourhood in the ways they liked best. It is a powerful tool for community engagement and a symbol of the collective power of people to create change in their neighbourhood.

We also used Grapevine, a technology that delivers sound pieces via a WhatsApp chatbot, to disseminate information and help bridge the gap in disseminating local news and community stories. We aim to use this effective communication tool and break-down legal jargon via a Street Vendor parcha (handbill) to inform a larger population of street vendors about their rights and responsibilities until SVA (2014) application remains ambiguous on-ground.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.