Placing Work, Mapping Places — Stories of Raghubir Nagar’s women informal workers

In India’s cheapest second-hand clothes market, women have to reclaim public spaces to assert their right to livelihood constantly

Most markets have sellers, customers and a permanent place or a platform to buy and sell. However, Ghode Waali Mandi in west Delhi’s Raghubir Nagar is no ordinary marketplace. It houses the most extensive and cheapest daily second-hand cloth market in India, comprising close to 1500 Gujarati women as sellers, no fixed customer base, and a negotiated place, which is only available from 4 am until 11 am, barring Sundays. In the remaining hours of the day, it becomes a gated public space with tin roofs, iron columns, a cemented plinth, and zero activity. In this unique haat (flea market), the morning-to-night contrast is distinct, and its constant dissolution and reoccurrence make it an integral place for economic sustenance.

On entering the mandi, you are greeted by rows of blue jeans hanging on fences along the road; sarees and dupattas flowing from terraces and balconies, and piles of clothes packed and displayed at the edges of streets. You will see tent walas and band walas – all servicing the wedding halls of neighbouring Rajouri Garden – near the famous Ghode Waala Mandir, and lines of utensil stores that are integral to a unique trading ecosystem practised here.

In this street vendors’ community, and all across the neighbourhood, people live and vend old clothes and other items that they source from different parts of the city. Here, community dictates work, and work dictates the neighbourhood, i.e. work-community-housing is inextricably integrated.

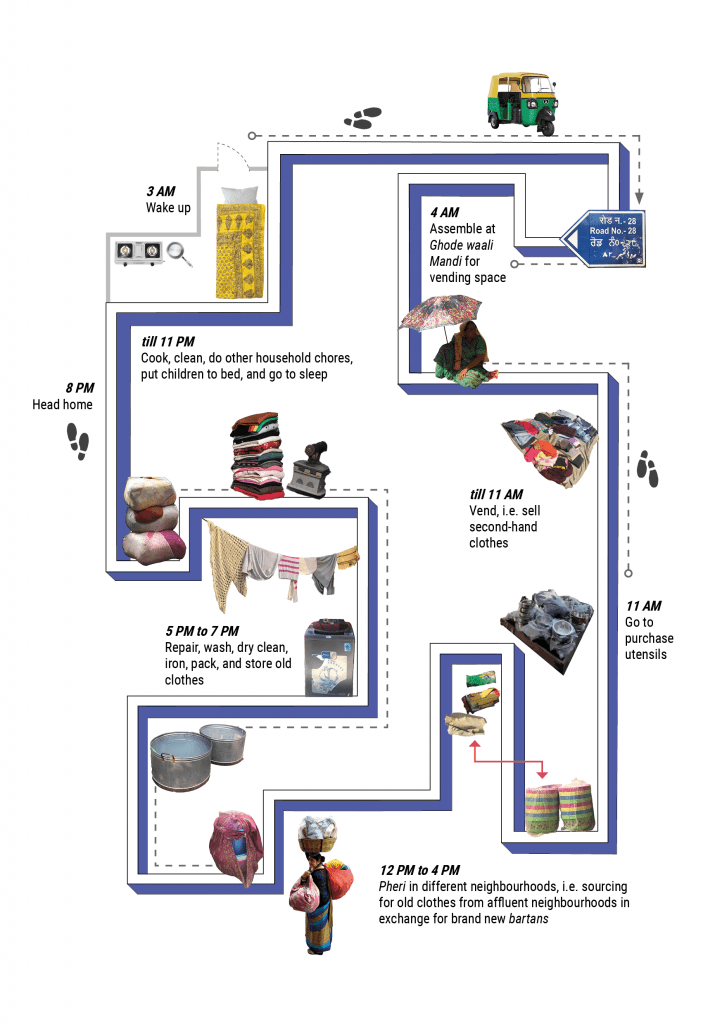

A walk through its tiny gullies will show you that the texture of the cloth trade is strewn across public spaces, hens and rabbits scrabble past, and men sit around in corners playing cards or talking in circles. Amidst this, women walk hastily through the crowds with no time to lose and sometimes shouting at the top of their voices — these are the pheriwaalis of Raghubir Nagar who spend an average of 15 hours in the public realm sourcing, vending, travelling, and doing household chores, with little to no time for leisure.

The daily reclamation of public spaces as workspaces is seen predominantly as “encroachments” and rarely as the making of a productive place or placemaking). The thing about patterns of informality is that the persistence of everyday activity at the same spot makes it a permanent fixture in the city. However, with no support or legitimacy, these groups become vulnerable stakeholders of the city, subject to harassment by the local authorities and facing regular violence by the state and men.

With a significant proportion of the female labour force on the decline, women vendors constitute about 30% of the total street vendors working in the informal sector and are key contributors to Delhi’s urban local economy, yet largely invisible from dialogue and action in top-down planning.

We tend to view informality as a source of chaos and disorder, a result not just of our mindset but of over 70 years of design and planning practices that refuse to imagine different possibilities. To make a difference, we need to look at the informal economy as a driver of development and inclusion.

Through the four-part series, Placing Work, Mapping Places, we aim to take you through the lives and livelihoods of pheriwaalis and informal workers. This group comes from varied histories and dares to dream of and seek re-imagined and dignified workplaces. The series will cover work-community patterns, the Street Vendor Act (2014), the politics of placemaking, the correlation of leisure and faith, and on sleep and night-time economies.

Locating Work in Public Spaces

When we travel through cities, we come across tall buildings, vibrant streets, and orderly junctions with traffic signals. However, what marks a city apart is never its larger-than-life infrastructure — the dense road networks or 24×7 bus stops or plush pavements – but how different groups of people interact with it.

Let us deep-dive into the public realm of New Delhi.

Public spaces of Delhi are unique because of their diversity — no two streets or neighbourhoods mirror each other – a product of numerous planning paradigms and a long migration story. For example, the vibrant food lanes of Chandi Chowk look and feel vividly different from the circular colonial corridors of Connaught Place. The complexity lies in including diverse people and groups classified according to gender, class, caste, age, disability, sexuality and work patterns. They are equivalent users of the public realm and have always been marginalised in our cities’ design, development, and dialogue.

Public spaces, transit systems, and pedestrian infrastructure in cities across the globe are known to be predominantly designed for the full-grown, able-bodied, upper-caste male subject. This urban landscape foregrounds the livelihood patterns of women who have a long-standing relationship with public spaces. Beneath this lie invisible systems and networks of urban supply chains.

Urban areas provide a variety of housing, social infrastructure, public spaces, open spaces and green spaces as forms of built infrastructure, which influences the nature and pattern of physical activity of an individual and a community. Work is one such physical activity intrinsic to a better quality of life. However, not all work gets support from existing provisions of urban infrastructure which was evident during March 2020 when the pandemic and the imposed battery of lockdowns forced millions of informal workers to return to their rural hometowns from cities on foot.

In conversations with the women of Raghubir Nagar, what would have been a qualitative research study on the devastating impacts of SARS-CoV-2 on urban, informal livelihood patterns resulted in a 15-month-long iterative practice – of storytelling, mapping and archiving the past, present and future re-imaginations of work and mobility patterns of female self-employed, informal workers based within the community and prevalent across Delhi.

What sparked our curiosity at first glance was the unravelling of century-old, informal trade networks and supply chains, which still occupy the public realm and significantly reduce garment waste reaching the landfills in our city.

Contextualising the Trade

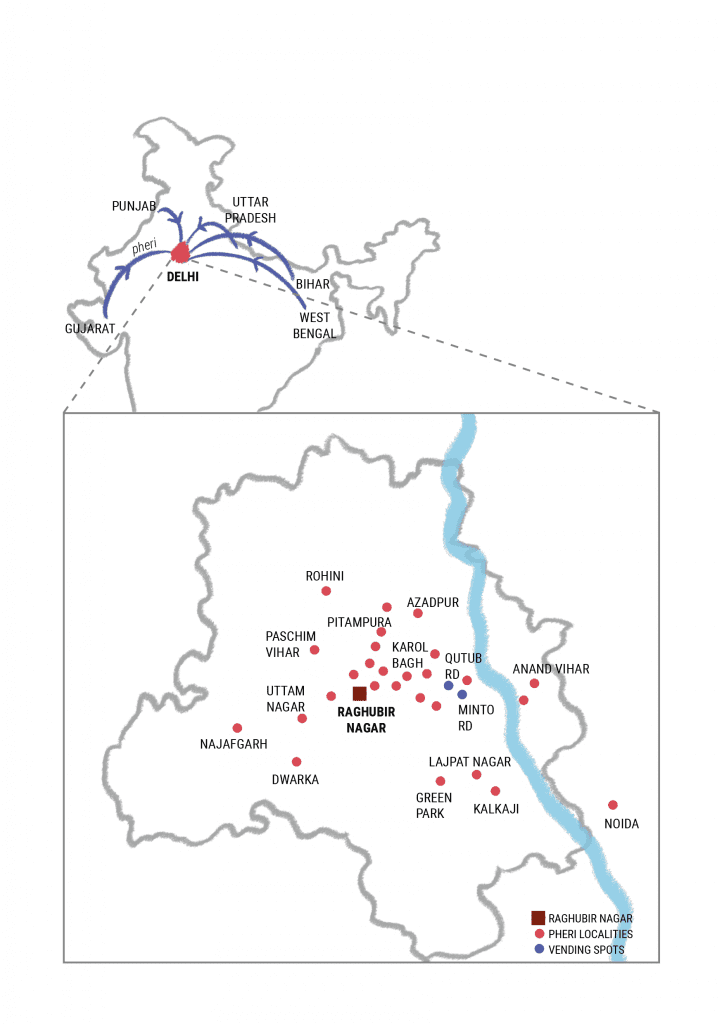

Colloquially, the term pheri refers to an age-old tradition of Gujarati women vendors doing the rounds to source second-hand clothes in exchange for utensils from relatively well-off neighbourhoods in the city and the outskirts.

The trade is a chain reaction set in motion by a phone call from a “madam” who puts in a request for bartans (typically utensils of steel, glass or plastic) to the pheriwaali. She purchases the utensils in the exact quantity demanded from a formal shop in Raghubir Nagar. Then, she goes on pheri, where the bartans are handed over to the “madam” in exchange for a gathri (a bundle) of second-hand clothes. It is barter-based, solely on a bargain informed by their expertise in utensils and fabrics, which adds to the size of their gathris and replenishes the stock of clothes for the coming weeks.

As women, pheriwaali find it easy to access these houses and enter them, which would be difficult for male vendors. The women have a long-standing rapport with the “madams”, so much so that they now receive orders for dinner sets and bone china, which are then exchanged for second-hand clothes, says Sona ben, a street vendor from Raghubir Nagar. The woman vendor may even choose to make an unscheduled visit based on negotiations made at the entry point with the security guards of the neighbourhood.

These sourced second-hand clothes make their way back to Raghubir Nagar and are sorted, rafu-ed (repaired), washed, embellished with sequins or lace, packaged out in the gullies and dried on park railings, and then finally sold at the adjacent Ghode Waali Mandi before dawn daily and the Mahila Bazaar on Minto Road in central Delhi on Sundays.

In a city like Delhi, change is a constant. And the pheriwaalis, who have long been a staple of the city’s vibrant street markets, are no strangers to adaptation.

Usha ben, a resident and street vendor previously, used to go on weekly pheri trips to find old clothes from “madams” living in upscale neighbourhoods. She remembers visiting the neighbourhoods in South Delhi once, but this has become impossible now because colonies are now gated and guarded. So, her routes had to change.

Her only access now is to the lower-middle-class and working-class neighbourhoods in some parts of West and North Delhi, where the income bracket is around Rs 20,000–30,000 per month and is easier to access.

In her work, ‘Circles of Value: A Study of Working Lives of Informal Sector Traders in Delhi’, postdoctoral researcher Raphael (2022) alludes to the ever-evolving pattern of this trade owing to Delhi’s changing social and spatial geographies. For decades the pheriwaali would vend on Road Number 28, the main artery passing through Raghubir Nagar. But as the city grew and traffic increased, the vendors faced a new challenge: finding a new home for their market.

In 1975, the local authorities allocated them an enclaved area next to the Ghode Waala Mandir, a move aimed at addressing the challenges posed by the growing traffic on the streets. This space came to be known as the Ghode Waali Mandi and would go on to become the largest second-hand market in the city. However, this shift was challenging. Many vendors had spent their entire working life on the streets and had to adapt to a new way of doing business. The mandi brought with it its own set of issues, including the imposition of a Rs 10 “fee” per bundle of clothes to be paid to the mandi gatekeeper every morning before being let in.

Situating Raghubir Nagar, its Origins, and its Evolution

In West Delhi, Raghubir Nagar is flanked by the affluent neighbourhoods of Tagore Garden and Rajouri Garden on one end and the Najafgarh drain running through on the other.

Most pheriwaali belong to the Waghri caste and have roots in Gujarat. Originally a nomadic tribe, the Waghris were deemed criminals under colonial administration. It has been more than 70 years since Independence and the subsequent revocation of the Criminal Tribes Act, yet they continue to be marginalised.

One of the primary sources of livelihood for the Waghris has been the pheri trade. The community has practised it for generations across Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra. Over a century ago, this women-dominated trading group made its way to Delhi.

In 1962, the Waghris were given a piece of land in Raghubir Nagar to establish their community. They set about building shanties, shops, and places of worship, and by 1977, they were allotted plots of land. Soon, the small colony grew into a thriving community. In this hub, much of the rural culture of the migrants remains with the Gujarati Samaaj heading and overseeing the vending market.

Most vendors in Raghubir Nagar are members of SEWA (Self-Employed Women’s Association), an organisation having roots in Gujarat, which has a massive on-ground presence in the area. Members also include migrants from Bihar, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh, but the women of these communities are predominantly home-based workers and do not engage in the cloth trade.

You can compare the whole Raghubir Nagar area to an open factory with spaces designated for different steps in the chain. Clothes are washed, dried, and sorted in the neighbourhood’s open spaces. Women sit together in parks, repairing and embroidering these clothes. Most alleyways and park railings are allocated to drying. Houses in the area have designated spots or rent space in godowns where these materials are then stored in gathris (bundles). The relationship that people practising the trade share with the neighbourhood is unique and an embodiment of the city’s symbiotic linkage between work and home.

However, public space only becomes safe for some despite being abuzz with people and work activities. Raghubir Nagar continues to be riddled with crime, and women hardly go out for reasons other than work. Men drinking and gambling in these spots in the late evening hours and night is an alarming cause for concern, so women are rarely seen relaxing in public spaces other than a few parks.

To counter the multiple threats to the continuity of the vending trade, such as Covid-19, the women started doing other work, such as selling anything they could find. The Rapid Assessment Survey of women street vendors in Delhi, carried out by the Institute of Social Studies Trust (ISST) in April-May 2020, found that 97% of women vendors had completely lost their livelihoods, and more than half had taken a loan to survive during the lockdown.

Other threats to the trade include police brutality. Sangeeta ben, a resident of Raghubir Nagar, says that earlier, the city’s people were much more empathetic to each other, but that is no longer the case. The police have ordered a crackdown on street vendors despite having the requisite documents. The police and other officials continuously harass the women vendors, and most of their earnings go into paying bribes so they can continue vending at their spots, they allege.

The rise of fast fashion in recent decades has also affected the clothes trade. With trends changing every season, the number of clothes people discard is higher now; however, these materials’ quality has declined. The pheriwaali’s profits depend on the quality of these clothes, which have little value.

In this respect, these women can also be seen as silent environmentalists who increase the life cycle of fast fashion clothes by recirculating them and preventing them from landing in the dump yard. But climate change has also been a significant factor in affecting the pheriwaali’s lives. Intense heat levels during the Delhi summers have had adverse effects on the women, and going for pheri now comes at the cost of their health.

On the one hand, paani ke pyau (safe drinking water stands), tripaal (tarpaulin sheets for shade) and women-only public toilets were basic demands of the group of pheriwaalis. Reality dictates that they control the levels of water they drink so they do not need to use a toilet too often.

Although the current generation of street vendors wants their children to avoid adopting this profession from them, improving the trade could create work opportunities for the younger generations of the community. There needs to be a significant shift in this business to keep the practice of street vending alive. It can be re-defined using a combination of digital and physical interventions to transform public spaces into dignified and productive places of work. This could possibly help revive the idea of a pheriwaali who now stands erased from Delhi’s imagination.

(The authors are part of City Sabha, an interdisciplinary platform that imagines empathy in city-making through deliberation and reclaiming of Delhi’s public spaces. All essays in the series originate from a 15-month-long socially engaged practice, Aao, Jagah Banaye!, with informally working women of Raghubir Nagar.)

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.