Tangled In Red Tape, The Disability ID Card Process Is Steeped With Gender Barriers

Khushi, 18, was elated to get admission to her dream Delhi University college to study English literature. Then, the teen, who was diagnosed with a visual impairment at birth, ran into a tough hurdle – the college asked for an up-to-date disability ID card within the next 15 days. Khushi herself had been waiting for two years to get one.

The central government introduced a definitive disability ID in 2016 replacing all the old ones – the Unique Disability Identity Card (UDID), which aims to become the only document needed by disabled persons to access social benefits. But a BehanBox investigation found that a host of issues affect its implementation. These problems multiply for women and transgender persons with disabilities.

Bureaucratic blocks, the digital divide and a baffling verification process that puts power in the hands of healthcare professionals are issues that make the process of securing a UDID a nightmare. Let us take the case of Khushi, who chooses to go by her first name, to understand some of these issues.

Khushi was diagnosed with retinopathy of prematurity–a vision impairment caused by abnormal development of blood vessels in the eyes of premature babies–soon after she was born in 2004. When she turned 5, her family secured her a certificate stating that her disability was permanent. All through her school life, Khushi used this document.

Before her Class 10 board exams, the family decided to update her disability certificate. After registration began an unending wait for Khushi to be summoned to a government hospital for medical verification. Whenever she was asked to furnish a disability document in this period, Khushi would show a copy of her UDID application and her old disability certificate.

When she contacted Eyeway, a help-desk for the blind, in 2021, it was suggested that she visit the nearest district hospital to verify her application. Over three visits, she managed to get her application verified. But the UDID card remained stuck in the process pipeline.

So when the DU college demanded a new disability certificate with her updated photo or the UDID card within 15 days, she was worried. There was no way she could get this done in a fortnight. Frustrated, she wrote a series of tweets on October 5: “I’m frustrated, anxious and disgusted”, “I’m disliking being disabled at the moment. thanks to having to prove my disability just to get into higher education”.

I'm frustrated, anxious and disgusted.

— Khushi 👩🏼🦯 (@BlindGrlMusings) October 5, 2021

probably not the right person to talk to right now because I'm disliking being disabled at the moment.

thanks to having to prove my disability just to get into higher education.

Her tweet was noticed by the Disability Rights Alliance (DRA) India, a coalition of advocacy organisations, which with the help of the National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People, a non profit organisation, managed to get her application expedited. She finally got her UDID card within 24 hours, nearly four years after she put in an application for it. “If my tweet hadn’t been noticed, my admission would have been cancelled,” said Khushi.

Khushi’s story is not a rare one as our investigation shows.

Less than 25% disabled have essential documents

In 1995, the Indian government passed the Persons With Disabilities Act (PWD Act), with the aim of providing social security benefits for the disabled and promoting reservation in education and employment for them. The rules of the act stated that a medical board, constituted by the central or state governments, would be empowered to issue disability certificates, mandatory for availing government benefits.

But 27 years have passed since the act came into effect and 71.2% of disabled Indians do not have a disability certificate, as per a 2018 National Sample Survey report. One of the main purposes of the UDID card is to bridge this gap, but it has not succeeded in doing this in the five years of existence.

In March 2021, a parliamentary standing committee said that the “process of issuing UDID cards is slow as a large numbers (sic) of disabled persons have not been able to get the disability certificates. Such delay in the attainment of the objective of UDID…is unjustified”.

As of December 15, 2021, 6.5 million UDID cards have been issued. But this is just 40% of the number of disability certificates (16 million) that have been issued and covers less than a quarter of the 26.8 million disabled persons enumerated in the last census a decade ago.

Since the 2011 census, the Rights to Persons With Disabilities Act (RPWD Act) has been passed, replacing the 1995 act and expanding social security benefits to include 21 types of disabilities as against the earlier 7. This likely led to an increase in the official count for persons with disabilities.

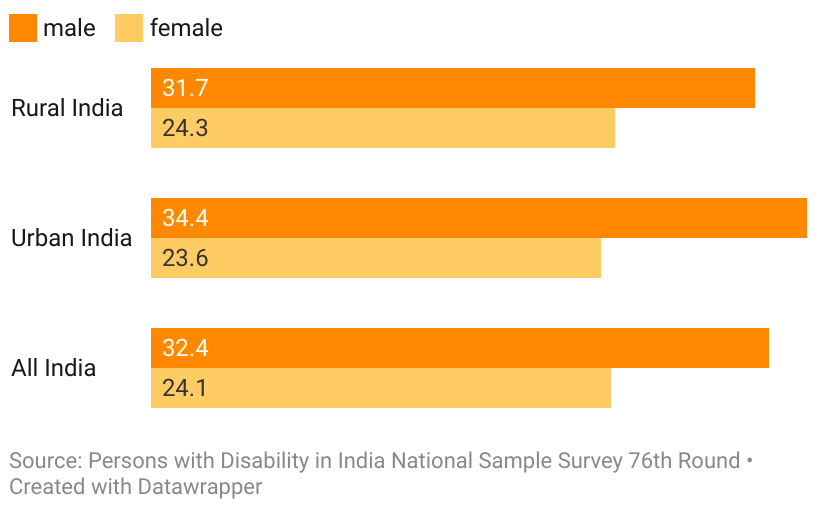

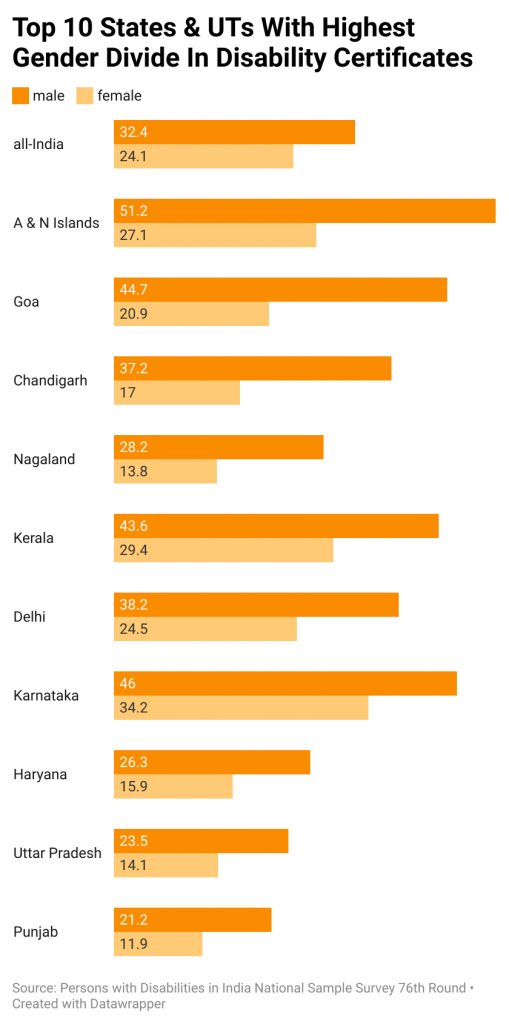

The 2018 NSS report is based on these 21 types of disabilities and highlights the significant gap in access to disability certificates. The report also highlights how this gap is gendered. Less than a quarter (24%) of women with disabilities have disability certificates against 32.4% men. The gap is widest among urban males and females—23.6% of women in urban India have disability certificates and 34.4% men do. In rural India, 24.3% of women and 31.7% of men with disabilities have the certificates.

Gender Gap In Disability Certificates in india

Across genders, the lack of a disability certificate also creates barriers in seeking justice. An April 2018 report by Human Rights Watch highlighted how after a 15-year-old girl was raped in Delhi, the police refused to report her disability because she did not have a disability document.

Gendered gaps in disability aids; cost barriers too

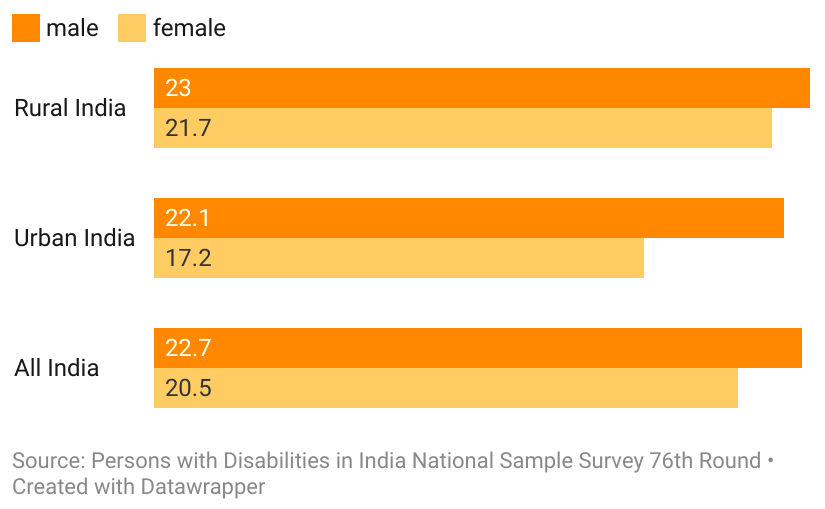

There are also gendered gaps in the distribution of government aid. One in five women with disabilities received aid from the government, as per the NSS report, 2.7 percentage points lower than men. In urban India, 17.2% women received aid against 22.1% men and in rural India, the figures were 21.7% and 23% respectively.

Gender Gap Among Persons With Disabilities who Received Aid From Government

The government has not yet released sex-disaggregated data on UDID cards. But other than the online nature of filing the UDID application, the verification process for both the forms of certification is similar. For a disability certificate, a medical board constituted by the central or state government conducts an examination and issues the certificate with disability percentage and permanence of the disability. For the UDID, a medical authority has been given this task.

Given the similarity between the processes, many of the existing gendered gaps remain. Women with disabilities, generally, have to depend on their family for transport, which adds to more costs, making it a significant barrier, said Meenakshi Balasubramanian, co- founder of Equals Centre for Promotion of Social Justice, an organisation focusing on knowledge and capacity building for disabled persons and advocacy.

“We have heard instances of families not choosing to spend so much money to access the certificate because they are not clear on the benefits and also because they feel that the benefits are not worth it considering the cost,” said Balasubramaniam. Since the application process requires multiple trips, families have to deal with income loss and also seek out and spend more on accessible modes of transport. This issue affects women with disabilities more, said Balasubramanian.

Digital divide

In 2016-17—the financial year the UDID was introduced—only five state governments were generating these cards. Since then, more state governments started issuing UDIDs and in 2019-20, nearly 2.9 million cards were issued across all states and union territories except Ladakh. Over these years, state governments adopted a hybrid online and offline model for the applications.

This changed in June 2021 after the central government issued a notification making it mandatory for state governments to grant these certificates only through the online mode. The digital divide creates yet another barrier for women with disabilities: only 15% of women in India use the internet against 25% of men. This divide becomes more prominent among persons with disabilities.

A 2019 survey of 2,000 Indians found that India has a 37% gender and disability gap in mobile ownership—81% of men without disabilities have a mobile phone compared to 51% women with disabilities. Among persons with disabilities too, there was a significant gender gap. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of men with disabilities have a mobile phone, 13 percentage points more than women. The gap grows sharper for mobile internet usage. Only 19% of the women with disabilities interviewed in India have access to mobile internet compared to 36% of men.

With most women with disabilities not having access to mobile devices and internet, they would have to travel to district disability rehabilitation centres (DDRCs) where such facilities are offered, said Balasubramanian of the Equals Centre, adding to existing barriers of travelling and added spending.

‘Treated like I was incompetent, brainless’

On November 18, 2021, Shivangi Agarwal was at a government hospital to undergo the verification process for her UDID application when she went live on her Instagram account. Crying, she spoke of the violence and discrimination she faced at the hospital. This was her third visit to the hospital since she filed her online application on November 6.

On her first visit to the hospital, Agarwal was asked to come the next day as the one doctor who verified disability applications was not available. The next visit she spent five hours refilling the application she had filed online and getting X-ray scans and physical evaluation. She was then asked to go home and wait for a call.

On November 17, she was asked to visit the hospital the next day. There, Agarwal says she was screamed at, touched and prodded without consent. “One of the men [claiming to be a physical therapist] followed by a woman took me to a curtained private area of the same room and the man started touching and examining the movement of my upper limbs,” said Shivangi in a statement she issued after the incident.

As the staff continued the physical evaluation, Agarwal demanded to know why she had to have another physical evaluation. The response, she told BehanBox, was “extremely rude and condescending”. He then started deleting details from the earlier physical evaluation report. “He started cutting off bits based on what he saw, instead of actually doing the proper examination,” she said.

Based on the new evaluation, she was assigned a disability percentage of 86%, significantly higher than the 70-80% bracket that the first physical therapist had estimated. As someone who had just learned to drive, a lower disability percentage would have made it easier for her to secure a driving license and health insurance, she said.

When Agarwal argued, she said she was “treated like I was incompetent and brainless for daring to suggest that I could know my own body”. As she continued to appeal, the doctor in charge increased the percentage to 88% and then again to 89%.

The hospital in its response to the Quint said that the behaviour of the staff was cordial and that the disability percentage was calculated based on a government notification. (Released in January 2018 this is a detailed guideline on calculating the disability percentage for individuals but not all doctors follow these processes, say activists.)

Random assessment practices

“Most doctors just look at the person and think that this looks like 53% or 75%,” said Kiran Nayak, a disability rights activist. “They don’t follow the policy or the government order.” He also alleged that some doctors demand a bribe to report a higher disability percentage – only those with over 40% disability are eligible for most social security benefits. They ask you to pay Rs 5,000 or Rs 10,000 for 75%, he claimed.

The medical guidelines look at disability only from the medical perspective and do not consider the complex nature of discrimination faced by persons with disabilities, pointed out disability activists. “It [disability percentage] not only reduces a person to mere abstract numbers, but also does not take into account the various other factors which work in tandem with disability to make the experience of marginality and disadvantage particularly complex and multi-layered,” said Ishan Chakraborty, an assistant professor in the department of English and a person with deafblindness.

The process also puts more power in the hands of healthcare professionals, which could lead to increased discrimination, particularly against trans persons with disabilities. Trans persons face extensive stigma and discrimination from healthcare providers, found a 2019 review of 67 research papers. The various forms of harassment and discrimination that transpersons reported in these studies include verbal and physical harassment by hospital staff and co-patients; insensitive and rough physical examinations by staff and healthcare providers’ refusal to touch them.

Other fears for transgender persons

For many trans persons reaching the verification stage of the UDID process is even more complicated. Shivraj Chhatria, a transman with disability, says he has not found the time to change his original name or the sex assigned at birth. He still uses the disability certificate issued in 2012 with his dead name. This is true of all his other ID documents as well. He faces a lot of problems because of this, he says, and he has been meaning to change his documents but he has had no time. “I just go to work and come back and sleep,” Chhatria told BehanBox.

While Chhatria can apply for a UDID card in his dead name, there is no clarity on how his name and gender can be corrected later. This is not a rare case, many transpersons do not have identity cards in their preferred name and gender. The training manual for the UDID does not specify detailed steps on changing of name, gender or other details but mentions that “only super administrator of Web applications will be able to edit data after upload”.

BehanBox tried contacting D.K. Panda, the undersecretary in the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities at the Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, on the issue of changing details in the UDID. The story will be updated when we receive a response.

For transgender persons with disabilities, adopting their preferred gender identity could also mean violence and alienation from disability benefits. “Two trans persons with disabilities from Telangana said they were hiding their gender identity because if they mention it, they will be deprived of basic facilities given by the government,” Shampa Sengupta, an activist working for disability and gender rights, wrote in November 2020. “Both of them stay in a government hostel for adult, disabled, unemployed youth which is free–there are separate such hostels for men and women, and none for the transgender persons. One of them also mentioned that once, some local police officials saw them participating in a pride march and threatened them that they will “reveal” their identities, which could cut them off all the disability benefits they were so far getting from the state.”

Beyond all this, the UDID process in its design is discriminatory, say critics, becaue it assumes that everyone is trying to game the system. “The assumption is that the applications are fake and the applicants are not disabled candidates,” said Vaishnavi Jayakumar of the Disability Rights Alliance, who noticed Khushi’s tweets and helped her out. Moreover, limiting the authority of verification to only a few government doctors has meant long delays and backlogs. “So if somebody doesn’t have a compelling enough story, and if they don’t have a contact in the state, then it is tough, and that is so pathetic,” she added.

[This report is part of the Spotlight Media fellowship. You can read the previous stories in the series here, here and here]

[The fellowship is a collaboration between Rising Flame and BehanBox to report on the violence and exclusion faced by women and trans persons with disabilities in India.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.