The Triumph Of Sharmila Devi And Tamil Nadu’s Women Leaders

Sharmila Devi (39), the youngest dalit sarpanch of Thirumanvayal panchayat in southern Tamil Nadu’s Sivagangai district, has pulled off what none of her upper-caste, male predecessors could in 50 years–bringing drinking water to the village.

“Thirumanvayal had uppu thanni (salt water). The villagers had to go to the nearby villages to get their daily supply,” she said. “I have seen this since my childhood. I always wondered why we could never solve this problem.”

The water crisis is also the reason why Sharmila, who had studied upto grade X, chose to contest for the panchayat president’s post in 2011 when it was reserved for women from the scheduled castes. Till then, the president’s post had been monopolised by Kallars, the dominant landed community in the region.

Thirumanvayal’s muddy soil does not allow retention of groundwater. The only solution was to request the neighbouring panchayat of Sarukani for water.

Sarukani’s panchayat members were first irritated with the request. “They were already sharing water with a few other panchayats, so naturally they were upset,” Sharmila recalled with a bright smile. “But, all that mattered to me was to persuade them to somehow share water with us.”

Sharmila also got Sivagangai member of legislative assembly (MLA) S Gunasekaran to intervene. It took her more than a month of negotiations to get every influential office in the district involved and get Sarukani’s panchayat to agree. “This is the last time we are giving water to anybody,” the village head had declared.

Soon after, a new borewell was dug at Sarukani and a pipeline laid to transport water to Thirumanvayal. Sharmila got a 2,000-litre water tank set up in the main village and created a network of mini power pumps and tanks across the 18 hamlets of the panchayat. “I don’t know why it took so many years to solve a simple problem,” she said.

Sharmila Devi is one of 40 panchayat heads, past and current between 2011-2016, IndiaSpendspoke to in six Tamil Nadu districts to understand how women’s leadership has changed local governance. These included Sivagangai and Tirunelveli in the south, Dindigul in the centre, Nagapattinam in the east, and Krishnagiri and Dharmapuri in the northwest of the state.

In a four-part series published in March 2017, IndiaSpend profiled women panchayat heads who broke caste and gender barriers to carve strong careers as local leaders. Contrary to the popular belief that women panchayat heads only served as proxies for their power-hungry male relatives, we found that 60% of them functioned independently. They also had in-depth knowledge of panchayat accounts, central and state funding schemes and the local bureaucratic structure.

In this series spread over five stories, we look at how women’s leadership in Tamil Nadu’s villages has evolved over two decades, how they are succeeding despite limited finances, caste oppression and violence and why it is tough for them to move upwards in the political hierarchy.

Reservation for women leaders in panchayat, introduced in 1996, has changed the face of rural governance in Tamil Nadu. In the last series, we saw that women leaders invest 48% more money than their male counterparts in building roads and improving access, and tend to concentrate on not just improving the supply of water in dry districts but also its quality.

Why is grassroots leadership important for women? We found that it empowered women in many ways. It has given them a voice and agency and prestige within the community. It gave them the access to the highest levels of bureaucracy like the district collector, the commissioner of rural development and higher elected representatives like MLAs and members of parliament (MPs). Women are executing large budgets and lobbying for extra funds.

More importantly, it has changed their self-perception as leaders and created role models for other young girls and women.

Lakshmi, the soft-spoken, diminutive president of Jakkeri panchayat in Krishnagiri district, recalls her meeting with Anbumani Ramadoss, the former union minister for health.

“I had gone to meet him with other panchayat presidents. Suddenly, he asked me to come to the stage and share my experiences,” Lakshmi said. “I was shy but I walked up because he called. I was scared but then I spoke for an entire hour. I did not know I could speak.”

“When I grow up I want to be like her,” Jyothi, her 15-year-old niece, standing next to her said with a smile.

Female leadership has also increased the access other women and marginalised groups had to the panchayat chiefs. Women could now walk up to them without any hesitation and demand services, a freedom that most male leaders did not allow.

Twenty years of grassroots women’s leadership in Tamil Nadu

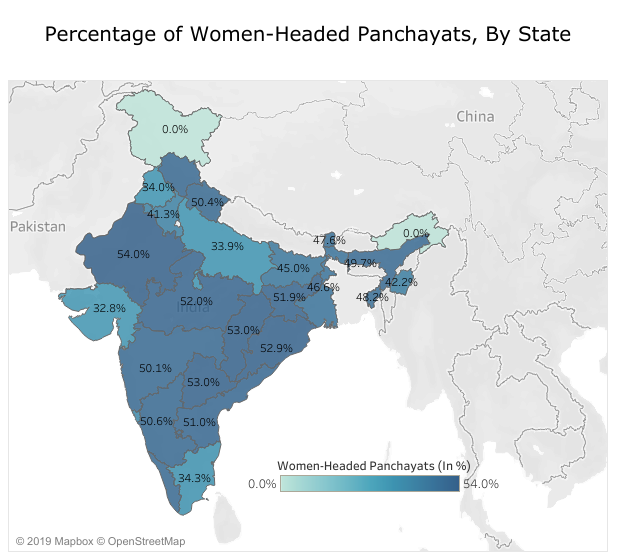

Women in Tamil Nadu were elected to gram panchayats–the lowest tier of rural governance–for the first time in 1996, after a third of seats (33.3%) were reserved for them under the new Tamil Nadu Panchayats Act, enacted after the 73rd and 74th Amendments to the Indian Constitution.

For the first time in 1996, women were called thalaivi, the feminine for “leader” in Tamil. Till then, panchayat leadership was the preserve of men from dominant castes. This change ensured greater representation for women in general and other excluded groups, particularly scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Many states, such as Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, have since then extended the reservation of seats for women to 50%.

In 2016, Tamil Nadu announced that 50% of seats in local bodies would be reserved for women for the local elections that year.

As mentioned earlier, our interviews showed that most women leaders charted their own path with little interference from men. The degree of autonomy from male relatives varied: We noticed, for instance, that dominant castes were more controlling of women leaders.

In Devakottai block of Sivagangai district, for example, we found that four women–two each from SC and general categories–of the seven heading panchayats functioned independently. In the Kalaiyarkovil block, all the nine women interviewed–six dalits and three from the dominant Thevar community–invested massively on roads, water, toilets and so on with men playing no role in their work. And in Thally and Kelamangalam blocks of Krishnagiri district, areas that are hilly and with reserved forests, five of the nine women we interviewed were independent leaders. Of them, three were from the general category, and one each from scheduled castes and tribes.

But, none of the four women panchayat heads from the dominant Vanniyar caste we interviewed in the Uthangarai block of Krishnagiri were allowed to function independently by their male relatives.

In one of the panchayats we visited (name withheld for the safety of the woman leader), the brother-in-law landed up as soon as he heard that she had visitors. He stood outside, next to a window, his gaze fixed as the woman panchayat leader spoke in a nervous and barely audible voice.

But in most cases, women panchayat leaders exhibited a growing political consciousness. Even though the panchayat president is a non-party position, 43% women in the study belonged to a political party, mainly the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam.

As many as 30% of the women we interviewed said they would stand for re-election in the upcoming panchayat elections, even if they did not represent a seat reserved for women.

Beyond this, women leaders in Tamil Nadu have also been influencing policy decisions at the state level. Early in 1997, they organised themselves into the Tamil Nadu Women Panchayat Presidents Federation, the first-ever in the country, to lobby for important policy-level changes.

In 2001, they lobbied with J Jayalalithaa, who was then in the opposition, to fix the panchayat president’s term for 10 years. Tamil Nadu was the first state in the country to do so.

Kalpana Satish, who was closely associated with the formation of the federation and who has trained women panchayat leaders, has an interesting anecdote to share about that meeting with Jayalalithaa.

“When they made the demand for reserving seats for 10 years, Jayalalitha looked at them and said mischievously: ‘So you want to get elected again’.

The women replied: ‘It will take us five years to just understand the system. We need another five to make a change’.”

The last term of the state’s panchayats and other rural bodies ran between 2011 and 2016. But the Madras High Court declared the election notification for 2016 null and void due to non-compliance with Rule 24 of the Tamil Nadu Panchayat (Elections) Rules, 1995. Opposition party Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam filed an affidavit to the effect that the reservation to scheduled tribe population was not proportionate to their population.

Women leaders went beyond assigned duties

As mentioned earlier, women panchayat heads tend to spend more than their male counterparts in large capital outlays, especially on road infrastructure. If we were to look at the capital outlay per household, women were spending Rs 15,515 on improving access and men Rs 13,488. Men spent significantly more on rural electrification (Rs 3,229.65) than women (Rs 343.42). On water supply, men spent slightly more (Rs 12,869) than women (Rs 11,537).

These are significant investments because they show women going beyond the assigned powers and duties of gram panchayat presidents. Gram panchayats, according to the Tamil Nadu Panchayats Act, are mandated to only provide basic services like water, sanitation, drainage, streetlights, burial grounds and road repairs. The funds they receive are often inadequate to provide even basic services. This means the women leaders lobbied hard for additional capital outlays.

The last IndiaSpend series showed that women panchayat presidents in Tamil Nadu, apart from investing in basic services, have also been building schools and public health centers though they have limited powers in the field of education and health. Apart from this, they are also actively campaigning against social problems such as child marriage.

Women have also taken on powerful lobbies in the state–the sand mining, land mafia, for instance. They are also fighting illegal encroachments and industrial pollution, as the following stories show.

Women’s rural leadership has gone beyond issues that are of immediate concern. Take for example the political campaign demanding reimposition of a ban on liquor in the state after the government lifted it in 2001. There was also a campaign that went beyond the state boundary–the protest against the two-child norm which barred candidates with more children from contesting panchayat elections in Haryana and Rajasthan.

We discuss here some of the strong initiatives undertaken by women leaders in Tamil Nadu’s panchayats:

Not just investing in drinking water, also making sure it is clean

When she became the head of the Nachangulam panchayat in Devakottai block, Rajanikandham, a dalit, was dismayed at how little her predecessors had done to deal with water scarcity. “I contested mainly to bring water to everyone in our panchayat,” she said. “In my time, I created three large borewells, 15 mini borewells and three overhead tanks. Now everyone in the seven hamlets of Nachangulam gets water.”

Women presidents in Devakottai block were spending around 10%-20% of their revenue on water, like their male counterparts in other panchayats. But in three of the 12 panchayats headed by women, they were spending between 30%-40% of their total revenues on capital outlays–digging borewells, laying pipelines, providing for large and mini water tanks in all the hamlets. This is significant because pipelines till then catered mostly to dominant caste areas bypassing entire dalit settlements.

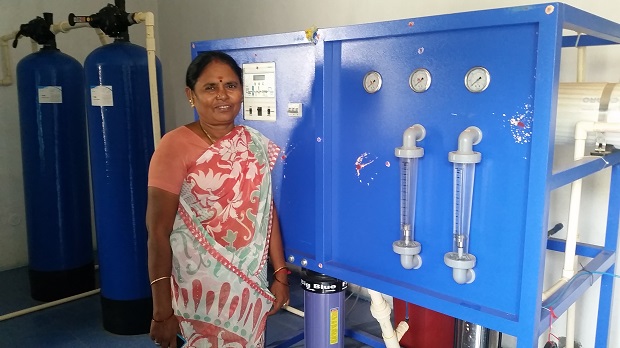

Women were also investing in sophisticated water systems to ensure pure drinking water, as mentioned earlier. In Kalaiyarkovil, where the water is brackish, five of the seven panchayats running reverse osmosis (RO) purification systems were headed by women, according to data obtained from the block development officer.

Mazharkodi Dhanasekar of Melamarungoor, K Kaleswari of Maruvamangalam and Rajeswari of Kuruthangudi panchayats in the block lobbied for extra funds with their local MLA for these RO systems that cost upwards of Rs 600,000, or 60% of the annual panchayat budget for a population of 2,000 in remote regions.

Till then, in all these panchayats, residents had been buying water from neighbouring villages at Rs 30 a pot from private operators. They now need pay only Rs 5 to the panchayat that operates the RO system.

“Water in these parts in a valuable commodity and people should know its value. That is why we charge a small amount,” said Mazharkodi Dhanasekar.

Meagre funds mean having to lobby hard for extra resources

Kalpana Ravindran is the dalit president of Vadagapatti panchayat in Dharmapuri district’s Harur block. When she had gone campaigning for votes, her prospective constituents had only one demand: If she could get the village roads laid, they would ask nothing more of her.

“I met a young girl who told me her cycle gets punctured on the kacha (rough) road. She cycles to the school. She told me, ‘When you become the president, you should lay roads’,” she recalled. “I can never forget the girl’s demand. So when I became president, that was one of the first things I did, using the Rs 30 lakh under the Tamil Nadu Village Habitations Improvement Scheme.”

Women in Devakottai block were spending between 15%-25% on capital expenditure on roads, much more than men (1%-10%). Rajanikandham of Nachangulam spent 47% of her panchayat’s revenue on building roads.

It is worth remembering that regular panchayat revenues do not allow for large capital expenditure on road building. This means that the women leaders are lobbying hard to extract extra funds. The State Finance Commission (SFC) grants every panchayat Rs 5 lakh (further reduced to Rs 3 lakh after the enhanced grants from the 14th Finance Commission) and an additional sum based on the village population. Nachangulam, for instance, gets SFC grants ranging from Rs 530,000 to Rs 700,000.

With limited powers, they still do a lot for education, health

Sidhamallamma belongs to the Irula tribe, traditional snake catchers. When she was elected Padiganalam’s panchayat president in Thally block in 2011, she made women’s health a priority in this remote area. Situated among the craters of granite mines, women here have to often deal with early marriage, frequent pregnancies, anaemia and malnutrition.

In Krishnagiri district, 47.4% of rural women between the ages of 15 and 49 were anaemic, 2.2% were severely anaemic, data from the National Family Health Survey, 2015-16, revealed.

To bring better health services to her panchayat, Sidhamallamma got herself trained as a health worker in 2014.

“Two years into my tenure, the sub-collector had a special programme to train health workers from the community,” she said. “Because I was interested in women’s health, I decided to join. Even though I was illiterate, I made mental notes of everything.”

Unlike Kerala or Rajasthan, where the devolution index allows panchayats control over local education and health, schools in Tamil Nadu are controlled by the state education department, as are health institutions by the health department. But despite limited powers, women panchayat leaders have achieved quite a bit in the state.

In Nachangulam, Rajanikandham struggled in her tenure to lobby for an upgrade for the primary school to a middle school. She worked hard, making numerous trips to the district collectorate and education department to make her case.

Yet, in the Devakottai block office, it is not Rajanikandham who gets the credit. “Yes, she could get it done. But it was mainly because of the Brahmin panchayat secretary. You see, Brahmins are very intelligent,” said an official.

Campaigning against early marriage for girls

Shanti (40), who heads the Anchetty panchayat in Thally block, will herself stop an underage marriage if she has to. In 2016, her last year as president, she stopped four such illegal marriages. In one of those, she walked in just as the ceremony was to start.

“The girl’s family prepared at night for a quiet wedding but I got to hear about it. I went the next morning and forced them to stop,” she said.

Early marriage is quite common in the remote regions of Krishnagiri and Dharmapuri districts. In rural Krishnagiri, 25.3% of women in the 20-24 age age group were married before the legal age of 18. Dharmapuri reported the highest number of child marriages between January and November, 2017, data released by the social welfare department in Tamil Nadu showed.

In the forested, hilly panchayats of Krishnagiri and Dharmapuri districts, women panchayat leaders were campaigning against child marriage in six of the seven panchayats we surveyed, as we reported in the last series. Four of them were investing money in upgrading schools to higher secondary to curb dropout rates among girls–one reason why they were married off early.

“I have done many awareness programmes in the last five years,” Shanti said, reminiscing that she herself had to stop studying when she got married at 15. “I tell families that things have changed. There will be many health problems. Get your girls educated first.”

Fighting sand/land mafia despite threats to life

Rani Muniyakanu, the former president of Vaduvanchery panchayat in Vedarnyam block of Nagapattinam district, dared to take on the illegal beach sand mafia. Vaduvanchery, close to the coast, is rich with minerals like monazite, valuable for nuclear fuel and exported to countries like Singapore. No male panchayat leader had taken on this mafia before.

Rani had been watching the sand trucks pass through her panchayat for a long time and was aware that mining had messed up the village groundwater.

“The sand miners were digging up to 15 feet so the water level had decreased,” Rani said. “In these areas, you dig anything below 18 feet and all you get is salt water.”

As president, she unearthed information on the permits given for sand mining in her panchayat. “Sriram Industries and Ezhil Industries were the main sand miners here. We found out that they were operating beyond their license permits, mining in areas that they had no permits,” she said.

She mobilised her own panchayat and neighbouring ones and held massive protests at the offices of these industries. Though the protesters were arrested, they managed to get the attention of the media and the MPs and MLAs of the region. She then filed a case in the Madras High Court with available documentary evidence.

The High Court ruled in her favour, after which Ezhil Industries shut down completely. Sriram Industries, which, she alleged, offered her Rs 100,000 to pull out of the case, reduced their activities in her panchayat and shifted to another. It was a massive win for her. But she had to spend her own time and money fighting this case.

P Krishnaveni, as the 2017 series in IndiaSpend reported, is a feisty dalit panchayat leader, who was attacked close to her home in Thalaiyuthu Panchayat in Tirunelveli district for opposing land encroachers and corporate groups such as India Cements.

Jothimani Sennamalai, the former councillor of Gudalur west panchayat had similarly mobilised the entire community against illegal sand mining in Amaravati river in Karur district. For this, she fought a five-year long legal battle at the Madurai bench of the Madras High Court. It ultimately ruled in her favour.

This story was first published on Indiaspend on March 08, 2018.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.