Women Leaders Help In Securing Women’s Land Rights in Gujarat

- Vaishnavi Rathore

Geeta Ben Gamit, 42, is a busy woman. The Sarpanch ( village council head) of Bhatpur in Tapi district in South Gujarat was finishing signing papers for the construction of a new meeting hall in her Panchayat ( the lowest tier of governance), when we met her on a hot March afternoon in her office in this tribal district.

Gamit stood for the Panchayat elections in 2016 with one clear agenda: she “wanted to do something for the women in her village”. Her time in office is now filled with hearing requests of women about their widow pensions, payments under MGNREGA (a rural job guarantee program), and women’s land ownership. In her tenure, Gamit has seen an increase in the number of women who want to get their names added on to family land records under the Hindu Succession Act. Under its 2005 amendment, the Act entitles both sons and daughters to equal rights of inheritance to ancestral property.

While studies now suggest that women’s ownership of farmlands in India has increased between 2001 to 2011, only 13.9% of India’s agricultural land holdings are controlled by women, according to the 2015-16 agricultural census.In Gujarat only 16% of agriculture land is actually operated by women.

The sarpanch and the Panchayat office, along with the patwari (revenue official) play a crucial role in women’s access to land rights. The office is responsible for registering the death of the male member, who in most cases is the primary owner of land, preparing a family tree document (Varsai), and updating the land records with the name of the woman — all essential starting points for women’s land rights.

The entire process of registering women’s names in the land records can take anywhere between three to six months. An application stating the death of their husband or father along with copies of the land’s survey number needs to be submitted at the Panchayat office, which is followed by the preparation of Varsai by the Talati’s (village-level revenue officer) office. The Varsai is registered with the Mamlatdaar, district-level revenue official. A notice is issued to all the people listed in the Varsai, who have to agree in writing to the addition of the woman’s name into the document. It is only after this that the woman’s name is reflected in the land records.

This process is not an easy one for women. If they are able to resist their own family’s denial of land rights, the administrative process is a tedious one. Women have to travel long distances to the block and district level offices to find out the survey number of their land, an unfamiliar and daunting task. The Talatis demand anywhere between ₹200-₹ 700 to complete their paperwork as a bribe, several women told us.

Many women called this entire process “magajmaari (brain racking task).”

“I work closely with the Patwari to help fill forms of all the women who come to me for adding their names to the land records,” Gamit says.

“Mahilaye khule dil se baat karti hai mujhse, bhaaiyon ke saath thoda sandeh hota hai unhe (Women talk to me openly, with men they have some reservations)”.

In our in-depth conversations with twenty people, ranging from male and female sarpanches, women land owners, self-help group members, paralegal workers and activists, across six Adivasi districts in South Gujarat, almost everyone believed that the process of acquiring land rights for women would be easier if women occupied positions of power or through women led networks. The phrase we commonly came across was: “ek mahila hi mahila ka dard samajh sakti hai (Only a woman can understand a woman’s pain).”

How does having a woman political head or networks make this process easier?

Misogyny in Panchayats

About 100 kilometers from Gamit’s office, Usha Ben Gajjar, 42, is waging a battle for her land rights.She has recently relocated to Sagbada in Tapi district from Surat to lay claim to her legal right.

26 years ago, Gajjar’s father was murdered by his sisters’ husbands in a bid to take over 4.5 acres of farming land.

“They struck an axe into my father’s neck,” she recounts. The extended family still controls the “encroached land”, says Gajjar.“This land is not theirs. As a daughter I have a right to my father’s land under the law. They [the father’s sisters] cannot be rightful owners of this land since it is not ancestral.”

Under the amended HSA, a daughter of a coparcener by birth becomes a coparcener in her own right. Since ‘coparcenary’ includes the lineal descendants of a common ancestor,only Gajjar [or her siblings] and their lineage can be legal owners of the land.

Gajjar and her mother moved to Surat to start their lives afresh after relatives refused to relinquish the land after her father’s death. “But the thought kept gnawing at me from inside that it is my father’s land, which we [mother and I] have a right to. So I came back,” she says.

Back in her ancestral village,Gajjar met Usha Ben Vasava, a resident of the same village. Vasava was a paralegal with the Working Group on Women and Land Ownership (WGWLO), a Gujarat-based network of over 40 NGOs and community-based organisations that focuses on women’s land and forest rights and sustainable agriculture by women farmers. Paralegals trained by WGWLO are the first point of contact for land-related issues in the block, who help women in securing their land rights through legal education and administrative assistance

After a quick crash course on the HSA law, Gajjar and Vasava put all important land-related documents together. At the Panchayat office where she went to file her paperwork, however, she was met with resistance and misogyny from the members.

“They asked me why I had returned”, she recalls. “They made lewd comments, like asking me what time I would go to their home at night.”

26 years ago, when she went to claim her land rights after her father’s death, men would not allow her to speak. Even today, little has changed. One of the members even slapped her.

“A Mahila sarpanch would not have treated us this way. Even today, if a woman gets elected, it will be the best for our case, she will know the troubles we go through, the kind of treatment that a woman faces in the panchayat office,” Gajjar says.

Her extended family intimidated her with violence, burning her son’s food truck, a source of his livelihood.

“On one occasion when I demanded my land back, they chased us with big bamboo sticks. Kaali chased them back all the way out of the fields!” Gajjar laughs stroking Kaali, her adopted mongrel.

After working with Vasava closely, Gajjar was able to compile all documents needed, from her father’s death certificate, to the family’s varsai. Gajjar’s mother’s name was added successfully in the Varsaai, a partial victory for Ushaben. She will consider it a total victory when the relatives are removed from and her own name is added on the land records.

Sumitra Ben Gavit, a widow from Vansda in Navsari district, shares the experience of widows who approach male Sarpanches to claim their rights.

“When we go to male leaders for more information about schemes or the law, people in the village gossip about our character– widows who go to a man’s house”

Gavit, who successfully added her name to her husband’s land in 2018 after his death with support from WGWLO, now helps other women to access their land rights.

“I know this pain that women face when they do not have information and knowledge. This information is important, otherwise, so many will lose the agricultural land they work on and will have to do labor on other people’s farms”, she told Behanbox.

Land is an important economic resource that can assure financial stability for the women, especially in the event of the death of their husbands. Land ownership also helps in access to government schemes and entitlements.

Bhanu Ben Vasava, a farmer from Narmada district was able to buy a pumpset which costs Rs 28000 for Rs17000 rupees under a subsidy from a project under Agriculture technology management agency (ATMA). ATMA allows for sustainable agriculture by coordinating research, day to day management of agriculture at district level amongst other functions. Gavit was able to benefit from the subsidy due to her name appearing on the 7/12 form, a document that shows land ownership and cultivator status. Almost all women who had added their names on the forms were also availing of Rs 2000 each season under the PM-KISAN Yojna. In 2020, 87% of the state’s over 62 lakh cultivators had been successfully paid for 3 agricultural seasons [Rs 6000/year] under this scheme.

“Because our name [her daughter’s and hers] is recorded as cultivators, each of us gets this cash benefit,” Bhanu Ben adds. Her daughter, Premila Ben gently mocking her mother adds, “Before father died, my mother could not even step out of the house, let alone go to an office. Now she has become a bit more confident to even speak up to officials.”

Comfort of Women led spaces

The comfort that women share with their female Panchayat leaders allows them the space to demand accountability.

“Whether it’s about the land records, or other works like MGNREGA, women directly come to me to talk about their problems. More importantly, if I lack in my duties, wo mazak-mazak mei hi sahi, lekin mujhe bata deti hai (they tell me off even if it is in a tone of jest)”, says Lalita Ben Gavit, a Sarpanch of Shamghan, a village in Dang district on the Gujarat-Maharashtra border.

Laws such as the 73rd and 74th Amendments to the Indian constitution mandate at least one-third of the seats in local level governance institutions are reserved for women. In a patriarchal society women’s role as political agents as well as citizens is an evolving one.

Lalita Ben’s mother sporting traditional Dangi silver armlets, explains this reality and the importance of women leaders.

“Mahilayen yahan aadmiyon se sharmati hai (women here are shy of men). In a large meeting of men, or in front of elders, women do not speak. When I was younger, we would cover our heads with our dupattas, and if a man came to our house, we would ask their identity from afar.”

Even in instances where the husband of the woman Sarpanch exercises everyday control of the office, the presence of the woman leader still creates the space for women to articulate their needs and demands.

Kalpesh Bhai Gamit [40] is one such “Sarpanch Pati” — a term used to denote a husband who carries out the duties of the panchayat on behalf of his wife– who works closely with his wife, Sunita Ben Gamit who was elected the Sarpanch of Vyara Panchayat in Tapi district in 2016.

“If women feel uncomfortable talking about any issue to me in the office, they come home. They discuss it with my wife, who communicates their problems to me. When later I go to meet the same women, I ask my wife to accompany me, to put them at ease”, he told Behanbox.

The positive influence of women as leaders is most visible in instances of the social practice where women are labelled as witches or “Daakan”.

Fifteen years ago, Ratniben Bhabor of Limkheda village in Dahod district was labelled as a Daakan after a family feud where her husband and his brother fought over their ancestral land as an excuse to deny them their share. She filed a police complaint against her husband’s brother which forced him to stop calling her so publicly. But the stigma carries on, even to this day.

“After my husband passed away in 2017, my son threw me out of the house. I have been staying with my brother for the last 6 months,” she says.This is despite the fact that her name was added on her late husband’s land, including the house that her son has forced her to leave.

Bhabor is not alone. Single women who can potentially claim land ownership in Dahod are often labelled as daakan, reported independent journalist Monica Jha. The practice is common in Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Bihar.

Bhabor’s only hope of reclaiming her land and home is the Panchayat.

“Filing another police case is a long drawn process. I will have to spend hours and money, and who knows if the case will benefit me or not? I will go back to my home only when the Panchayat members discuss my case and rule in my favour,” she says as she breaks into tears.

When a woman raises a complaint against being labelled as a daakan, panchayat members often conduct the first round of negotiations to resolve local conflicts. But, the nature of interventions in cases of witch hunting is not always uniform: sometimes, local panchayat members have been found to aid perpetrators in a number of cases. Bhabor said that her male relatives had bribed a Panchayat to rule against her.

A 2016 study by Partners for Law in Development (PLD) in Jharkhand, Bihar, and Chhattisgarh had found that women’s groups, especially Mahila Samakya Sangathana, a woman’s group initiated by the government, played an effective role in restoring the dignity of the ostracised women.

Saarthi, a grassroots organisation based in Mahisagar district’s Santrampur, introduced a novel concept, ‘Mahila Support Groups’ (MSG) for helping women sarpanches. MSGs connect a woman Sarpanch with various Self-Help Groups or Mahila Mandals of their villages. The group accompanied women sarpanches to Panchayat or zilla Parishad (district council) meetings.

“With this support system, the mahila sarpanch did not feel lonely and timid anymore,” says Ravindra Bhai Sisodia from Saarthi.

“Earlier, the elected woman sarpanchs would not even come to the office.Their husbands would be handling everything. While ‘sarpanch patis’ have not vanished from the scene completely, elected women now at least work alongside with their husbands, if not completely independently.”

Geeta Ben Gamit, sarpanch of Bhatpur in Tapi district, who proactively aids women with processes of land ownership was able to win the panchayat elections through the support of such networks

Women Led Networks Aiding Land Rights

Gamit may have assumed elected office in 2016. But, her work with women’s groups stretches far back in time. As the former leader of the Sakhi Mandal, a Self Help Group (SHGs) that encouraged micro-savings in her village, she already had the trust of the women in her village.

“The SHG members encouraged me to stand for the mahila seat, they felt that if I came to power, a lot of women’s issues would get addressed because I would be able to understand it better.”

These SHGs have become a space for women to hold open discussions, transform into a support group in need and create larger impact.

We meet Usha Ben Valve, a member of an SHG in Narmada district who lives in a picturesque village on a hilltop, near the temple of the goddess Devmogra, a highly revered deity in the area.

“Next to this temple, government constructed a small shopping complex last year where those who rent a shop can sell prasad, food, or gift items. Our SHG group had also written to the Panchayat members asking for a space where we could put up a tea-stall and earn some extra savings for the group, but we were not given this space. We are continuing to lobby for it though”, says Valve.

“Earlier we could not even imagine going out of the house, let alone putting forth our opinions to the panchayat office,” she says. “But with training conducted by Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) in our village about women’s land ownership, we gained more confidence about our rights and are now even extending support to single and widowed women through our SHG itself”, says Kantaben Valve, another member of the same SHG.

“When we started doing training on land rights for women, we realised it is a complex issue to take up as it could create tensions in the society, especially from the male members,” says Usha Ben, a land paralegal worker with WGWLO network in Narmada district. “But since we had initiated SHGs years ago [through work by AKRSP], women and families already had a sense of trust with us. We were able to build up on this and introduce the concept of land rights.”

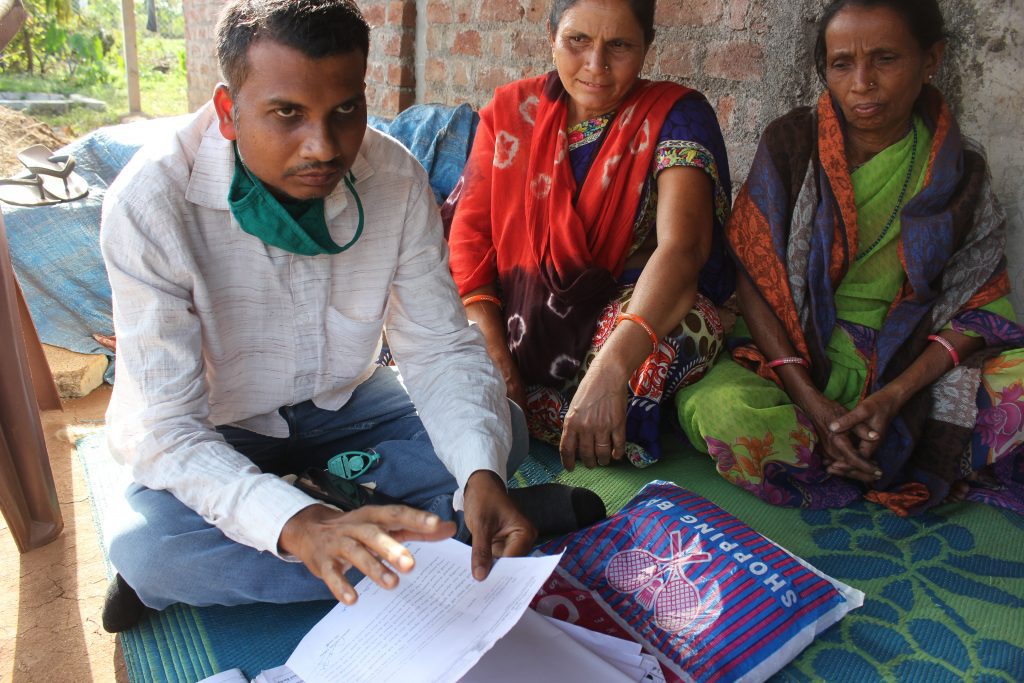

For Geetaben Gamit, it was the Swa Bhoomi Kendras (SBK) that helped her in her work as a woman Sarpanch in helping women to access their land rights. SBKs were formed by the Working Group on Women and Land Ownership (WGWLO) as spaces where trained paralegal workers help community members with understanding the law, organise the necessary documents and accompany women to various officials, if necessary.

Paralegal workers handle the cases of women from the beginning till their name is officially registered in the land records. Between 2017 and 2019, WGWLO has aided 842 beneficiaries to secure land ownership in the eastern and southern Adivasi belts of Gujarat.

Other forms of women’s leadership has helped women in gaining “atma vishwas” (self confidence).

For Mogra Ben Vasava, it came from having been the president of her village’s Forest Rights Committee in Dediyapada, Narmada district since 2007. Frequent trips to the block office, filing forest rights claims, understanding the law, and training about the procedures of land ownership for women, all helped her evolve as a leader.

It is not always easy, however.

“Male leaders don’t let many women flourish as leaders, especially if women are excellent at understanding issues, or confidently speak in front of them. Maybe they see them as a threat”, says Vasava.

She is planning to contest in the Zilla Panchayat elections next term while continuing to support other women in the village for securing their land rights.

While the Hindu Succession Act allows women rights enshrined in law, the road to securing them in reality is paved with many roadblocks. Women navigate these roadblocks with the support and shared camaraderie of many women — political leaders, community leaders and organisers, self-help groups among others.

This reportage is part of the WGWLO and Behanbox fellowship on women’s land, forest and farming rights in Gujarat

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.