Bengaluru Urban district, a prominent hub for readymade apparel in India, is host to over 750 garment factories. Together, they employ 2.8 lakh workers, 72 percent of whom are women.

Any disruption to the work, almost always disproportionately affects the women workers who are overworked, under-paid and are situated on the powerless end of the global supply chain.

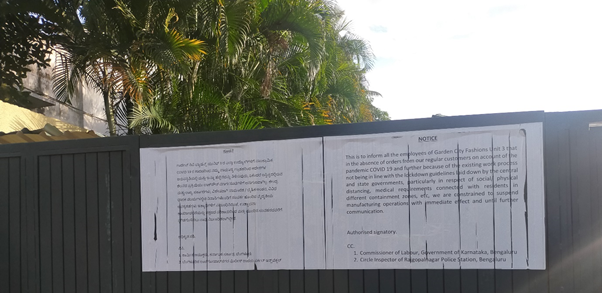

The economic crisis generated by the pandemic and the nation-wide lockdown exacerbated the precarity of the workers from June 2020, factory managements began downsizing and even closing operations entirely, citing losses due to a fall in orders from transnational apparel companies. Thousands of women garment workers in Bengaluru were suddenly left unemployed.

Factory managements were well within the ambit of their constitutional right under Article 19(1)(g) to reduce their workforce or close down their units. However, various judgements from Indian courts give workers the right to challenge closures and retrenchment and for state governments to scrutinise such moves. Moreover, workers are entitled to closure or retrenchment compensation, according to the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947.

Forced resignations have been an unfair labour practice in garment factories for a long time. When workers are forced to resign, factories can bypass the legal requirement to pay compensation or seek permission for retrenchment and closure. A recent study tilted ‘Forced Resignations, Stealthy Closures: A Study of the losses faced by garment workers during the COVID-19 pandemic’ by the Garment and Textile Workers’ Union (GATWU) and the Alternative Law Forum found that 69% of the women workers across 25 factories in Bengaluru were forced to resign.

Many women workers reported that they were presented with two options when their factory announced the closure–to resign and claim their dues or to stay and delay/lose out on their dues. This fear pushed a majority of workers to resign without challenge.

Workers were asked to resign immediately or at very short notice, which did not allow them any discussion amongst themselves and with family members or even finding other means of alternate employment.

Factory managements also created a multitude of scenarios to compel workers to resign. These range from discontinuing transport services which are crucial for women workers to reach the factories to simply asking them to stop coming to work. In some instances, factory managements told the workers that there would not be a human resources department to process their dues, if they resigned after the factory closure.

Managements promised workers, in some cases, that they would be re-employed when factories resume operations. This acted as both fear and incentive for the workers. They feared that they would not be re-employed if they challenged the demand to resign. Many workers thought that they would be re- employed later if they quietly resigned. Such promises also meant that workers would not protest or contest sudden closures.

These strategies of forcing workers to resign are not new and have been deployed even before the pandemic. However, the scale of forced resignation expanded during the pandemic. Coming soon after the nation-wide lockdown which left working class households with no income and savings and mounting debt, forced resignations multiplied the precarity of garment women workers.