Why Trump’s Tariffs Are A Feminist Issue

Women make up for a significant portion of the workforce in India’s four key US export sectors. From long-term wage cuts to increased debt burden, they will be most affected by the 50% tariffs

- Shreya Raman

A new tariff regime–ranging from 25% to 50% duties– imposed on Indian exports by the United States will have a devastating impact on key export driven, labour-intensive industries that employ a high volume of women workers.

The tariffs that came into effect from the midnight of August 27, while seeing a sharp 43% decline in exports– from the current USD 86.5 billion to USD 49.6 billion in 2026 — will impact the competitiveness and employment in the related sectors, as per a detailed sector wide analysis by the Global Trade research Initiative. These include textile, gems, auto parts, leather, agricultural products and marine exports, particularly shrimp.

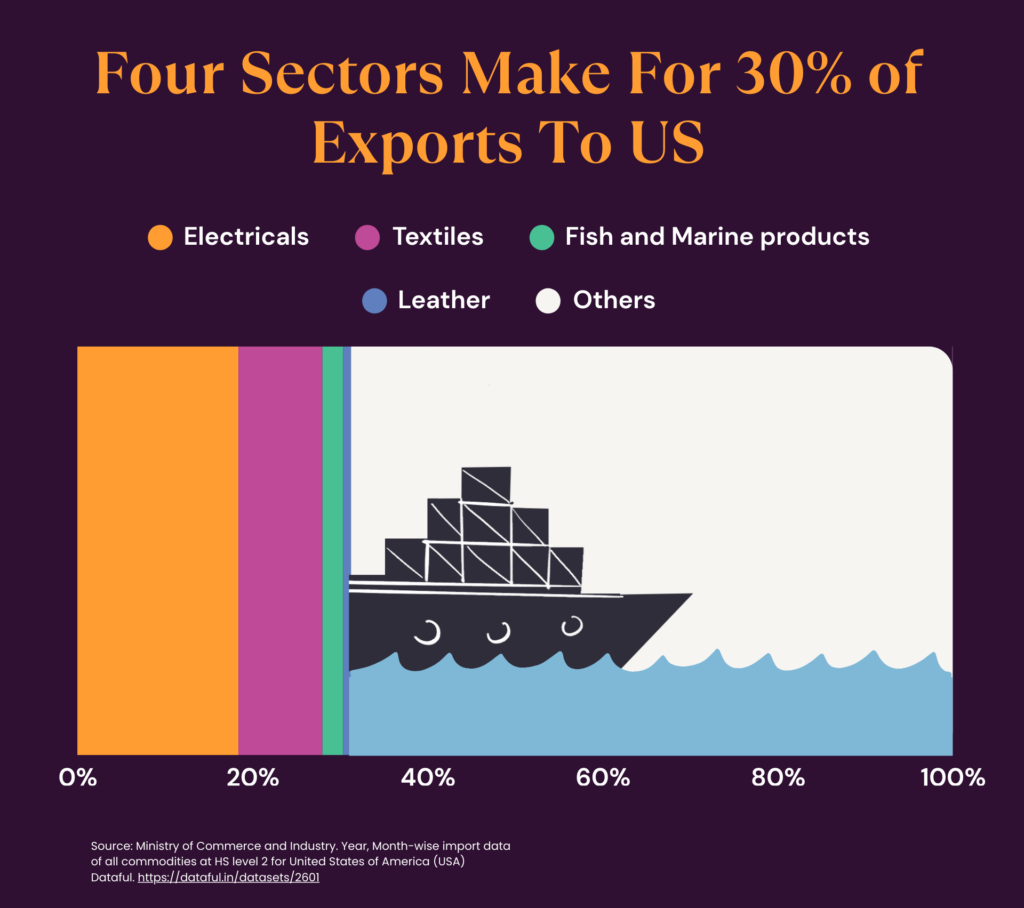

At least 30% of India’s exports to the United States are in industries that rely heavily on women’s labour, often in low-paying and at the bottom of the supply chain, our analysis of export data revealed. In 2024 alone, India exported electrical, textile, leather and fish and marine products worth USD 23 billion (Rs 675 lakh crore) to the US, all of which will have significant proportions of women workers.

On July 31, US President Donald Trump announced a 25% “reciprocal” tariff on Indian goods exported to the US. On August 6, he passed another executive order, announcing an additional 25% “penalty” tariff tied to India’s continued purchase of Russian oil, bringing the total duty to 50%, one of the steepest levies, alongside Brazil, imposed on any trading partner.

India has called these tariffs “unfair, unjustified and unreasonable” and maintained that it will not “bow down” and asserted its right to protect national interests. Prime Minister Modi urged citizens to purchase only Indian products and has announced GST slab reforms as a measure aimed at bolstering domestic consumption. There are also plans to develop other international trading markets.

Tariffs: A Feminist Issue

In his second term, Trump has introduced a sweeping global programme of tariffs to reduce the country’s trade deficit–the gap between the value of exports and imports. These include 15% tariffs on exports from Japan and South Korea to a high 50% tariffs on Indian and Brazilian exports.

Tariffs and taxation in general are a feminist issue, argue feminist economists and those advocating for tax justice. ‘National and international taxation are gender blind and tend to see taxation only from a functional revenue-raising potential rather than from a redistributive perspective,’ argues this brief from the Global Alliance for Tax Justice, a south-led global coalition for tax justice.

On the supply side, countries facing the highest reciprocal tariffs are major exporters of labour-intensive industries such as apparel and textiles to the US, where 80% of the workforce in the industry are women in low-paying jobs. The high tariffs are already forcing factories to shut down their US driven production lines, as we reported from Tiruppur and Dindigul in Tamil Nadu, disproportionately affecting women workers with reduced shifts and halved salaries, forcing them into debt and poverty.

From a consumer perspective, tariffs impact incomes of poorer households, as they tend to spend a larger proportion of their income on imported goods than those with higher incomes. Tariffs are considered regressive taxes, when applied uniformly, regardless of the price of goods or incomes of consumers. The Yale Budget Lab estimates that the present tariffs could lead to a 2% spike in inflation and cost American households between $3,400 and $4,200 per year. Since women make up 80% of all consumer purchases, are 35% more likely to live in poverty and represent two out of three of workers earning at or below minimum wage, and head 81% of single income households, any price increase will hit them harder, says this brief from the Feminist Majority Foundation. This is on top of an already existing “pink tax” where women’s versions of consumer products like razors, shampoos, clothes etc are priced higher than men’s items.

The Cato institute has dubbed this as the Trump administration’s most ‘anti-women’ economic policy that penalises goods and appliances like dishwashers that have freed women’s time.

Tariffs And India’s Women Workers

India’s exports have seen a consistent increase– from USD 18 billion in 2007 to USD 80 billion in 2024, with a 65% increase in the post-pandemic years. (full dataset on Dataful here).

This increase has been largely driven by electronics and ready-made garments, which constituted 15% and 10% of the exports in 2024 respectively. While leather (0.9%) and fish products exports (2.4%) are comparatively lower by proportion, the US is a significant market for the export-driven industries. Over 80% of leather products in India are exported, close to 22% of which are sent to the US. Frozen shrimp accounts for 66% of India’s seafood exports with 34% of the revenue coming from the US market.

Women, often from the most marginalised communities, make up for a significant proportion of the workforce in these industries. The leather industry is one of India’s biggest non-farm employers with 4.5 million workers, 40% of whom are women.

In the frozen shrimp industry, women constitute over 70% of the 8 million workforce, and they perform low-end processing jobs such as deheading, peeling and sorting shrimp in cold processing plants. In apparel and textiles, they make up almost 70% of the 45 million workers, while the electronics industry is known to largely hire young women because electronics manufacturing needs “small and soft hands for small pieces”.

In these export-driven sectors that are part of a global supply chain and where labour conditions are often dire and exploitative, economic shocks like high tariffs will cascade into unforeseen short and long-term impact, say researchers and labour economists. This will push them into debt, lower their employment opportunities and reduce wages in the long run.

“Across global supply chains, the US tariffs will make women workers vulnerable. Women are concentrated in labour-intensive, low paying, precarious jobs, whether it is processing or assembly line and men dominate more capital-intensive, technical and leadership roles in these spaces,” said Ashmita Sharma, executive director at Society for Labour and Development, a labour rights and support organisation with a focus on global supply chains, labour migration and gender justice.

In these industries, women are paid on a per-piece basis or low monthly salaries with tight deadlines in conditions that have adverse health impact, as we have reported. In the leather industry, women are mostly home-based workers earning Rs 8-10 per pair of shoes. Typically, they earn Rs 1500- Rs 3000 a month after stitching around 8-10 shoes a day. Few work in factories and earn between Rs 7000-9,000.

In the shrimp processing industry, a March 2024 report by the Corporate Accountability Lab unmasked the exploitative working conditions where most low paid women workers, often paid per kilogram of shrimp peeled or cleaned, are “ghost workers” with no contract, health insurance or social security.

Reduced demand from the US market due to high tariffs will lead to immediate cutback of vulnerable workers, particularly women, as men are engaged in capital-intensive roles like transport, machine operations and maintenance and handling of exports, said Ashmita.

Women in textile and electronics industries earn around Rs 10,000 and Rs 15,000 respectively while those processing shrimps are paid a monthly wage of around Rs 10,000 or daily wage rates of around Rs 300, depending on the location and the factory.

Impact of the Tariffs

While the full impact of tariff increases will be felt in the coming days, early reports show a developing slowdown in export driven industries and employment of workers, especially women.

The impact is visible in the most adverse ways in the textile industry. Tamil Nadu’s textile hubs, where the effective tariff for certain kinds of knitwear has reached 64%, our report showed how the costs to the producers are being pushed down the supply chain. Saraswati, a 35-year-old garment worker in Dindigul, and other workers in her factory were put on rotational shifts, i.e. three days a week, instead of the usual six days. Her wages were halved–from 12,000 a month to Rs 6,000. Companies are also delaying monthly wages, pushing women workers further into debt.

This came after months of women working overtime to complete the orders as the tariffs were initially announced on April 2, and then paused for a 90-day period. “Since there was so much uncertainty, a lot of the brands were asking the factories to fulfill their orders quickly,” said Deepika Rao, executive director of Cividep, a social impact organisation working in the labour space.

The shrimp processing industry – for which the US is the largest market – saw a 20% price drop in Andhra Pradesh, which accounts for a bulk of shrimp farming, after the 25% tariffs came into effect. Farm-gate prices in West Godavari and Ongole have plunged by Rs 40–60/kg for small-count shrimp. Processing plants in Visakhapatnam and West Godavari are cutting overtime and preparing for shift reductions as exporters report paused or cancelled orders, said the Global Trade Research Initiative report. In addition to the 50% tariff, shrimp from India also attracts a 2.49% anti-dumping duty and 5.77% countervailing duty, making effective tariff on the product over 58%.

“Our importers from the US have asked us to hold on to our shipments even for existing orders,” said Alex K Ninan, vice president of the Seafood Exporters Association of India.

Importers are shifting to countries like Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia whose exports are taxed at 19-20%, said Alex. “Other markets have also now realised that we are sitting on a huge inventory. So, in anticipation of [lower] prices, they have also asked us to hold our shipments,” he added.

In Agra, a leather footwear manufacturing hub, orders placed by American buyers for autumn and winters are in the final stages of production or ready for shipment. But buyers are telling the companies to hold shipments or share the losses. Many companies that had increased their capacity hoping to target US markets are effectively unsure of the future.

The impacts of these tariffs will depend on various factors, Deepika said, such as the product in question and the tariff imposed on it in competing countries. “They can differ from region to region and even factory to factory,” she said.

Alex said that seafood exporting companies have not yet taken any measures to layoff workers as they are waiting for relief measures from the government. No such measure has been announced yet.

Most export-oriented businesses maintain a small segment of permanent workers while outsourcing the rest of the work, said Neetha N, professor at the Centre for Women’s Development Studies (CWDS), an autonomous research institute. “So, when the demand for products reduces, companies will retrench these workers,” she pointed out.

The COVID-19 pandemic showed us how these shocks impact the most vulnerable workers. In Karnataka, textile factories illegally forced women workers to resign after a fall in orders, bypassing legal requirements to pay compensation or seek permission for retrenchment. For two months, 1,300 workers led sustained protests and submitted letters to the labour department and succeeded in receiving their dues of nearly Rs 45 lakh.

Weak Bargaining Power

Such collective bargaining, however, is rare and not without its challenges.

Since 2019, Ashmita’s organisation has been facilitating the formation of a women-led collective in the seafood processing industry of Gujarat’s Veraval. Alongside some resistance from employers, a key challenge lay in the limited space available for collective empowerment of women workers, as factories operated under stringent working conditions driven by international production requirements.

“Nearly 15-20% of the women workers are migrant workers who live in employer-provided accommodations and entry into these spaces is difficult,” said Ashmita. So, they started working with women workers who lived in villages around the processing unit and formed village-level committees, which fostered new ways of supporting worker voice and agency, rooted in principles of leadership, empathy and care. Despite caste dynamics between Koli, Kharva, Dalit and Muslim workers creating tensions, they have been able to create a shared space that brings different social groups together.

For home-based workers, such as those in the leather industry, the very nature of their work, which as we reported is not considered as work, reduces their collective bargaining power. “The smaller workshops and home-based units isolate women from freedom of association and collective bargaining. So then women workers become even more invisible, informalised and excluded from the more formal rest of the workforce,” said Ashmita

During economic shocks like the likely fallout of high tariffs, good social security coverage is essential, said Neetha, which will help workers tide through the impact, especially if the shock is short term and the industry is able to find its way back. Workers’ access to these social security systems are dependent on the level of formality and the specifics of the working conditions. While home-based workers do not get any of these benefits, formal workers in textile factories have more access.

With limited support systems, workers are compelled to choose more precarious and exploitative work or seek debt. “Women often have no financial cushion. They absorb the shock personally–by stretching food, taking up more informal jobs. That also pushes women into debt,” said Ashmita.

There are long-term repercussions too. “Fewer jobs leads to increased competition and will, in the long run, impact wage rates,” said Neetha.

As tariffs will impact 0.5% or 1% of India’s GDP, by some estimates, the impact will be disproportionately felt by women, said Mitali Nikore, economist and founder of Nikore Associates. In the longer term, unless there is a considerable expansion of the manufacturing sector, women will not find new avenues of employment, she added.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.