In TN’s Garment Factories, Heat Stress Is Leaving Women Workers Sick, Fatigued

The delivery deadlines of fashion brands and suppliers make no allowance for women who are forced to work in peak summer with poor access to water, sanitation and healthcare

With temperatures reaching 43ºC by mid-April this year, 5.2 degrees above normal, the textile workers of Erode district, a major textile production hub in Tamil Nadu, have been reporting frequent fainting spells, heat rash, yeast infection, and urinary tract infection.

“This year we are seeing an increased number of cases of workers with heat-related stress and dehydration,” said Thivyarakini, state president of the Tamil Nadu Textile and Common Labour Union (TTCU). “In the first week of May, 13 women garment workers reported to me that they were having rashes and increased white discharge. Underreporting of heat illness in the workplace is very common, resulting in the underestimation of the impact of heat exposure.”

Heat stress – a condition where the body is subjected to higher levels of heat than it can tolerate without physiological impairment – has a multitude of consequences. Fatigue is often the first sign but extreme heat also drains fluids from the body.

Maintaining a core body temperature of around 37°C is essential for continued normal body function, according to data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlighted by the International Labour Organization (ILO). Above this, physical and cognitive functions are impaired; and if the temperature breaches 40.6°C (heatstroke), it sharply raises the risk of organ damage, loss of consciousness, and death.

The effort to meet production targets in this heat puts many women at risk. Bhagyalakshmi*, a tailor in a garment factory in Dindigul, said the workers were expected to produce 1,000 units of garments per day, a high target given their uncomfortable work conditions.

Some of the other risk factors for heat stress in workers, as documented by the US Department of Labor, include high humidity, indoor radiant heat sources, limited ventilation, PPE and clothing, physical exertion and health problems.

The indifference of supplier companies and fashion brands to the plight of the workers means that workers are often labouring over long hours to meet tight delivery schedules in uncomfortable safety gear with poor access to water, sanitation and health facilities, we found in conversations with workers and labour rights activists.

Ganga*, a spinning mill worker in Dindigul, complained that her employers asked workers to get their own ORS packets to deal with dehydration. “After paying us hardly Rs 10,000 per month and making us work for more than 9 hours at 38-40ºC temperatures, six days a week, they want us to even bring our own ORS,” she said.

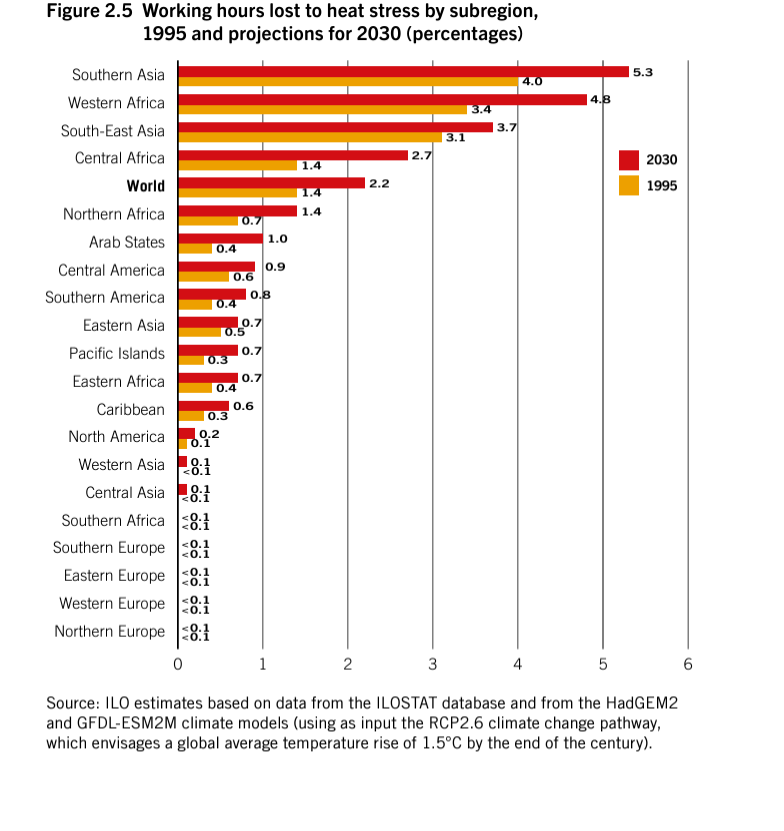

The extreme weather being experienced with increased frequency is a direct result of climate change and its impact will affect lower-income countries the most – those in southern Asia and western Africa are predicted to be the worst-affected. Heat stress has been found to be more prevalent in countries with deficits in decent work standards, like lack of social security and high rates of informal work. Tamil Nadu’s textile industry falls squarely in this hot spot.

No Cooling, No Ventilation

The textile industry in India has an estimated 45 million employees, and of them around 70% are women, making it the largest employer of women in the country after agriculture.

The conditions at many factories are horrific, say workers. We heard many complaints about the absence of cooling systems and water.

“Many factories do not have working fans or coolers to combat the heat and there is no proper ventilation. The temperature inside garment factories is a few degrees higher because many use tin sheets for roofing. During summer, bathrooms often do not have water in the flush or tap, creating an unhygienic environment,” said Thivyarakini.

She also pointed to the discomfort of working in summer months in the outfits mandated by factories. “Women workers feel suffocated in the multiple layers of clothing, including compulsory uniforms in certain factories and overcoats on top of salwars and sarees, masks, and caps,” she said.

To avoid using the bathroom, and also because the water is of poor quality, women workers often avoid drinking water and risk dehydration. Bathroom breaks are also severely curtailed and monitored by factory management. Ambika*, an ironer in a garment factory in Erode, said she fears she will faint from the extreme heat on the factory floor. “I know the risk of this is very high as I don’t drink much water during the day. We are not allowed to use the bathroom more than twice,” she said.

Many of them also skip meals. “The lunch we bring gets spoiled in this heat. The management knows this but we still have to work long hours and deliver,” said Lakshmi, a spinning mill worker in Dindigul. The lack of water and food saps the energy levels of the women whose work is anyway physically demanding.

Particularly Hellish For Women

There are women workers, such as Hema*, a tailor in a garment factory in Dindigul, who delay their periods with medication to avoid having to use toilets without a steady water supply. “The factory during the summer months feels like a pressure cooker,” said Hema. “ I know I can’t handle this extreme heat and my period pain together. If I take leave for my periods, I feel I will lose my job.”

Basic first aid for heat sickness is often unavailable in many factories, say workers. “The nurses in the factory are hardly equipped to handle workers fainting from heat stress and dehydration. There are not even sufficient ORS packets available in the nurse’s room, and now the management is asking us to bring our own ORS packets,” said Ganga, the textile worker from Dindigul.

For women, the heat is particularly hellish because it brings on rashes, urinary and vaginal infections that, in many cases, go untreated because workers’ have neither the time nor the wages to address them.

“I have been having severe vaginal irritation and also increased white discharge since the summer started. I also have had red rashes all over my body since April. The nurse in the factory told me that wearing cotton clothes would reduce the rashes and itching, but how can I afford cotton clothes with my wages? I can hardly pay for food and rent with the Rs 8,500 I earn,” said Chellamal*, a checker in a garment factory in Erode.

Summer is the peak season for yeast infections with the heat combined with sweat and moisture providing conditions for bacteria to thrive. Light cotton underwear and outerwear is usually recommended to deal with this. Adequate hydration and food are also vital to combat yeast infections. But the workers said they can afford none of this.

Delayed Impact

Heat-related fatigue can impact workplace safety and increase the likelihood of injuries. A 2021 paper titled “Temperature, Workplace Safety, and Labor Market Inequality” that looked at nearly 20 years of data on workplace injuries in the US found that a higher temperature significantly increased the likelihood of injury at work.

The study found that days when maximum temperatures were between 29.4ºC and 32.2ºC led to a 5%-7% increase in same-day injury risk, compared to days when temperatures were in the 15-20ºC range. Days when the temperature was above 37.8ºC, the risk of injury increased by 10%-15%.

The study also looked at risk of injury related to heat in different industries. In manufacturing, the researchers found that on a day when maximum temperature goes beyond 32.2ºC, the risk of injury went up by 7% compared to temperatures closer to 15ºC.

The impact of heat does not necessarily manifest immediately and on the factory floor and this means that it remains unreported, said Rajalakshmi Ramprakash, a public health expert. “Heat exhaustion is slow and insidious – its impact can be both in the short-term and in the long-term. Unlike common occupational accidents and injuries, the physical results of heat exhaustion like dizziness, nausea, and fainting, might happen after a worker reaches home,” she said.

Research on occupational heat stress in India is limited because of challenges like the lack of data, non-cooperation of industries, resistance to change among employers, and so on.

An HR manager at a garment factory said on condition of anonymity that though the maximum permitted temperature in a garment factory is around 30ºC, mid-March onwards this goes up to 36ºC and beyond. “In the afternoons, it goes up to even 40ºC. I know that it is very difficult to work in these conditions, but we have orders which we have to deliver on time – or else we will run into a loss, and won’t be able to pay the workers,” said the official.

Falling Productivity

Heat stress also has a significant impact on labour productivity., At 33-34°C, a worker operating at moderate intensity loses 50% of their work capacity, according to the ILO. And for workers whose wages are based on delivery of targets, this can have serious implications.

Based on 1.5°C global warming by the end of the century, 2.2% of total working hours globally are expected to be lost to high temperatures in 2030 – the productivity loss equivalent to 80 million full-time jobs. Working hours in southern Asia and western Africa, the worst heat-affected regions, could fall by 5.3% and 4.8% in 2030, respectively. This corresponds to around 43 million and 9 million full-time jobs in these respective regions.

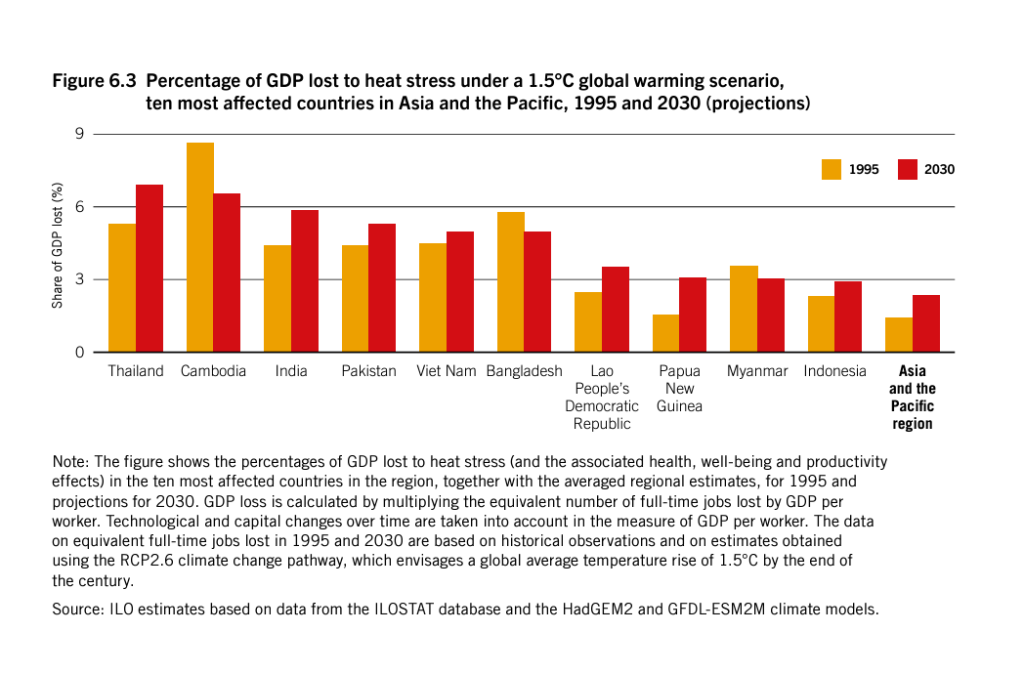

In southern Asia, India will be worst hit – it is projected to lose 5.8% of working hours in 2030. This is the equivalent of 34 million full-time jobs in 2030 as a result of heat stress.

‘Can’t Afford Compassion’

A production manager said that the excessive heat impacts productivity in summer months but he cannot afford to be compassionate – by offering more breaks or allowing fewer work hours – because of delivery deadlines. “If brands are going to penalise us for delays, how can I create a better workplace for my workers?” the manager said.

The economic losses caused by heat stress at work were estimated at US$280 billion in 1995. In 2030, this figure is projected to reach US$2,400 billion, with the impact being the highest in lower-middle-income and low-income countries.

Global textile supply chains are largely unregulated by national and international laws. Fashion brands take advantage of this by exploiting a poor and flexible workforce, made up of mostly women, while evading legal liability for labour and human rights violations. These abuses were widespread during the COVID-19 pandemic, when brands used the force majeure clause to abandon all responsibility towards workers and supplier factories.

They set high targets, tight deadlines, penalised delays even in the most dire of circumstances, and refused to pay textile suppliers. In turn, suppliers forced women workers to work at unsustainably low wages in poor conditions, thus putting their health and lives at risk. This crisis is likely to worsen as heat conditions worsen.

A production manager at a garment factory in Tamil Nadu said it is time suppliers and buyers factored the impact of climate change into their costs.

“As climate change worsens, I expect there will be longer and harsher summers in Tamil Nadu. We will have to re-think our factory’s overall design to support workers and maintain productivity levels during these months. Already, water is scarce and we have to purchase expensive drinking water. All this will increase the cost of production and garment suppliers who have low profit margins cannot bear the entire cost of it, without the contribution of fashion brands,” the manager said.

The ILO Hygiene (Commerce and Offices) Recommendation, 1964 (No. 120), stipulates that “[w]hen work is carried out in a very low or a very high temperature, workers should be given a shortened working day or breaks included in the working hours, or other relevant measures taken”.

Current purchasing practices need to be changed to ensure that this kind of exploitation is not possible. Lavinia Muth, the civil society representative to the steering committee of the German Partnership for Sustainable Textiles, said that brands now need to acknowledge the reality of climate change.

“Brands must acknowledge their complicity when garment workers collapse from heat stress. Purchasing contracts with sanction clauses when delivery dates are not met exacerbate this exploitation. I’ve seen it first-hand during audits and discussions with suppliers,” said Muth. “The result is repression and stress on the factory floor.”

The names of all factory employees have been changed to protect their identity.

All views expressed are of the authors and do not represent the organisations they work for.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.