[Readmelater]

Displaced, Jai Bhim Nagar’s Women Are Reclaiming Urban Spaces In Mumbai

Thrown out of their homes eight months ago in a demolition drive, the women of Jai Bhim Nagar are fighting for their right to housing. They are also reclaiming spaces to keep their cultural identity alive

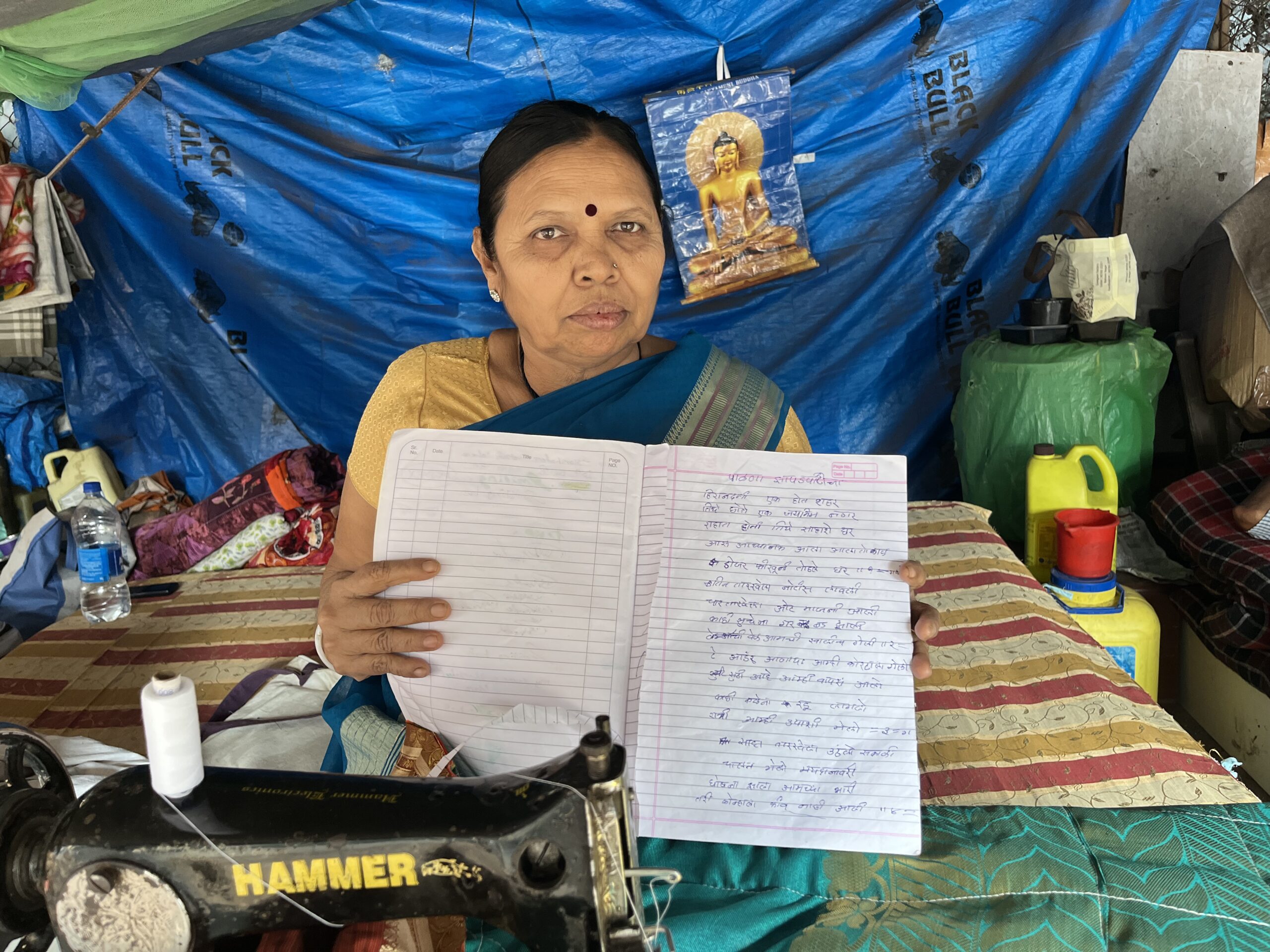

Sushila Khandare’s song ‘Palana Zopadpatticha’ documents the trauma of displacement of the residents of Jai Bhim nagar/ Priyanka Tupe

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.