Homes Razed, Tughlaqabad’s Women Agitate For Rehabilitation Rights

The bulldozers arrived with no notice, women allege, leaving them stranded without shelter or belongings

Subhawati Devi was fast asleep when just past midnight, a team from the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) arrived in her locality, in the Chhuriya Mohalla of Tughlaqabad Village, near the historic Tughlaqabad Fort on April 30, 2023. The team announced that all residents must vacate their homes and belongings and relocate elsewhere. Most of the residents of the neighbourhood are migrant workers from Bihar and West Bengal working in Delhi as daily wage earners and domestic workers.

Unaware of the warning, she went about her chores the next morning. But at around 9 am, as rain hit Delhi, she saw a swarm of bulldozers, fire brigades and ambulances arrive in her neighbourhood. Soon houses were being razed to the ground.

“I could not understand what was happening, but the first thing I did was grab all my important documents and run in the middle of rain,” says Subhawati Devi.

Mala (38), another resident of the village, claims that on the night of April 29, police officers in civil clothes arrived to survey the area. But they did not warn residents about an impending demolition. So the backhoe extractor aiming at her colony the next morning came as a shock. “I tried to get as many valuable materials as possible. But I lost my passbook, my medical reports and all of my savings. I have a thyroid condition, but without the medical reports, I cannot go visit the doctor anymore,” she says.

Situated in the capital’s South Delhi district, Tughlaqabad fort is one of Delhi’s mediaeval monuments. Built in the 14th century, by Sultan Ghiyassudin Tughlaq, the fort is a protected monument under the ASI. Approximately 2.5 lakh people live in the fort area.

Between April 30 and May 1, thousands of families living near the Tughlaqabad Fort were rendered homeless by the ASI’s demolition drive. Acting on a 2016 Supreme Court order that declared Tughlaqabad fort a ‘protected’ monument, ASI undertook the removal of illegal encroachments in the area. However, there is no clarity on the extent of this encroached land, says Kawalpreet Kaur, a lawyer with Human Rights Law Network (HRLN), and one of the lawyers who appeared for Mazdoor Awaas Sangharsh Samiti, an organisation working for workers’ rights and the key petitioner in the ongoing case in the Delhi HC demanding the rehabilitation of Tughlaqabad’s residents.

According to Section 20 of the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act, 1958, any new structure built within 100 metres of the protected monument – in this case the Tughlaqabad fort – is prohibited. However, residents claim that most of the houses that were demolished are 750 metres away from the fort. Curiously, many houses, including BJP MP Ramesh Bhiduri’s residence which falls under the 100 metre radius, were not demolished, claims one resident.

On April 24, the HC directed the ASI to remove encroachments in and around the Tughlaqabad fort within the next four weeks. This process was to be followed by a survey of the area, along with the establishment of proper rehabilitation plans, says Kaur. “Instead the authorities arrived with no proper notice that would allow the residents to gather their belongings, and proceeded to demolish their houses in the most immoral and unethical manner”, mentions Kaur.

The demolitions have aggravated the precarities faced by women in the area who already bear a disproportionate political and socio-economic vulnerability. As highlighted by Kalyani Menon in her study, demolitions cause women’s household reproductive labour to intensify causing significant losses to their independent incomes. Behanbox has been reporting on the gendered impact of demolition drives ( see here and here). Several women in Tughlaqabad’s Chhuraiya Mohalla who work as domestic workers, have lost their jobs. Amidst managing the stress of homelessness, and taking care of the family, women cannot go to work.

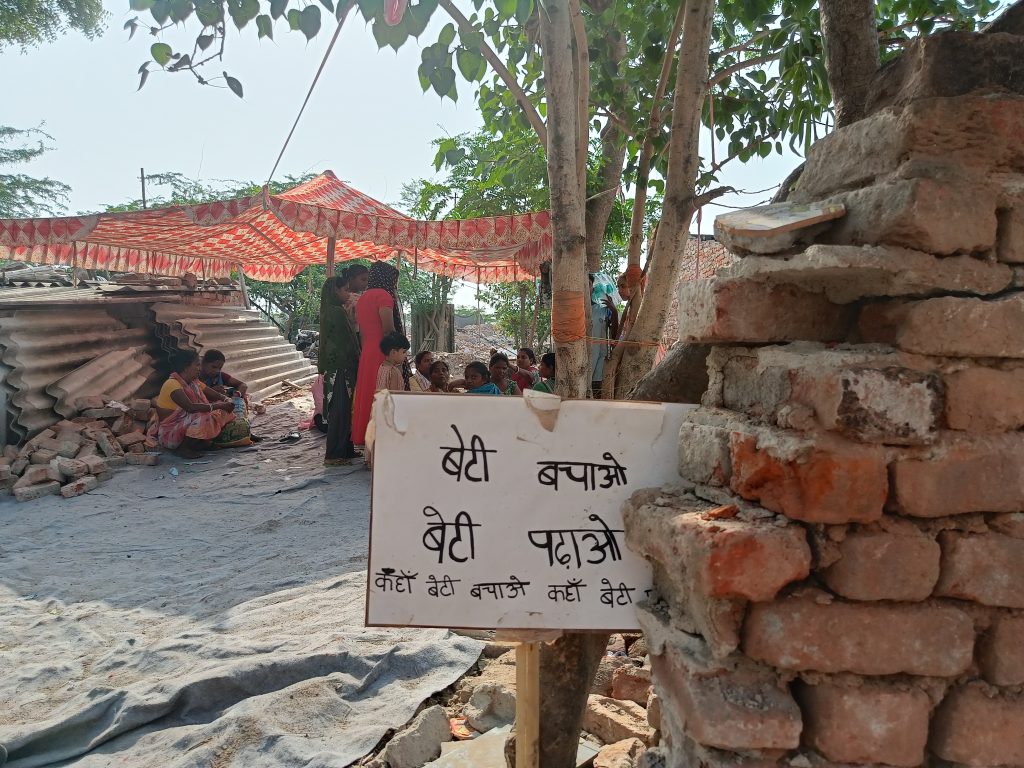

Women Protest

Right where the demolitions took place, a bunch of 10-15 women sit around a makeshift tent in scorching Delhi heat, demanding that they be rehabilitated. “Ghar ke badle ghar (a home in exchange of a home),” says Reena Sharma (40), weakened by an eight-day long hunger strike. Her condition is severe and she had to be hospitalised recently. A domestic worker by profession, Sharma decided to go on a hunger strike after witnessing institutional and state apathy around their homelessness.

The day after the demolition, bulldozers arrived to clear out the debris from the demolition. Sharma along with a bunch of women frantically reached for whatever remained of their houses; mostly bricks and other valuable materials, that they could use in the future to rebuild their houses. When they tried to stop the bulldozers from destroying the remaining pieces of their houses, they claim they were picked up by the police and beaten up in the police station.

“I could not bear the harassment, and the apathy any longer. So I stopped eating as a mark of my protest hoping that some justice would prevail. It has been more than a week and there has been no sign of hope. No one cares if we live or die,” says a dejected Sharma. She and her husband Jatinder claim that ever since she has been on hunger strike, police personnel have been arriving at the site to threaten them. “They have been asking us to leave, saying if we don’t then they have ways to make us disappear,” says Sharma.

In the last one week, women have had to move three times as the police continue to harass them, sometimes in the middle of the night. Just a few metres ahead, lies the residence of BJP MP Ramesh Bhiduri. Residents claim that Bhiduri has not once arrived at the site of demolition to check on them. “However, BJP goons arrive almost every night to intimidate us to leave from here,” alleges a resident.

To amplify their protests further, the women headed to Jantar Mantar this Monday to register their demands along with the on-going wrestlers’ protest. The residents have decided to continue their hunger strike and plan further protests at Jantar Mantar in the coming days.

Legality and Illegality

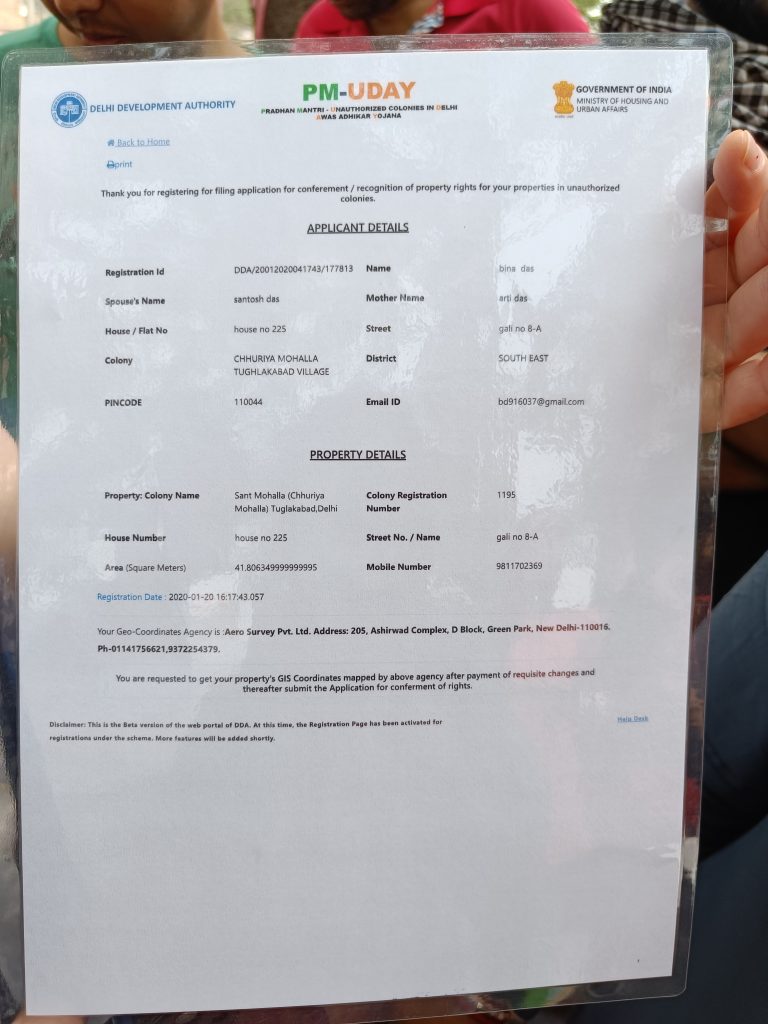

Suman Das (37), a care worker, has been living in Chhuriya Mohalla’s Bengali Colony for seven years. A year ago, she filed an application to register her land under the Pradhan Mantri – Unauthorised Colonies in Delhi Awas Yojana (PM-UDAY). The scheme launched by the Narendra Modi government before the 2019 elections, aims to regularise unauthorised areas in the capital and grant ownership rights to the residents.

Almost all the women BehanBox interviewed showed similar registration certificates, recognising property rights over houses in the unauthorised colony.

We spoke to Mukta Joshi, a lawyer with Land Conflict Watch, an independent network of researchers studying land conflicts, climate change and natural resource governance in India, to understand the legality of these documents. According to her, residents with a PM-Uday certificate clearly stating their claim to their property “should have been given the opportunity to present that claim. There should also have been some structure in place that would facilitate them to actually be able to come forward and approach the justice system with these claims…If they had been given this opportunity, things would have turned out differently.”

However, the 2016 SC judgement categorically listed the area around the Tughlaqabad fort as “encroached land”. Despite this, residents have been granted PM-UDAY certificates as recently as 2020. Joshi says there is a machinery of “tacit approval” by the government that allows residences to be built around areas which are deemed “unauthorised” or “illegal”.

“It’s not overnight that a basti (slum) or an apartment springs up. Structures have been here for many years – people pay electricity and water bills, and even make regular payments to government officials. But in the end, it’s always the ‘occupiers’ who are made to suffer” says Joshi.

Eviction, without rehabilitation

The Delhi High Court in 2010 held that denial of rehabilitation amounted to a “gross violation” of the fundamental right to shelter. For this purpose, the State must conduct surveys to identify persons eligible for rehabilitation, and carry out meaningful rehabilitation of each person, it added. This verdict was also later upheld by the SC in 2017, and reiterated by the Delhi HC in 2019, making rehabilitation surveys an essential part of eviction exercises throughout India. The UN guidelines also lay down how eviction guidelines require authorities to show that an eviction is unavoidable, and should not make people homeless.

But, it appears that the ASI has only acted on one judgement – the one on demolition. “It is always rehabilitation first and demolition later. But since there is such a rush to do the demolitions, the concerns of the people only come out at a much later stage”, notes Joshi. Kaur also expresses similar sentiments, “It is the responsibility of the ASI in conjunction with DDA authorities to first work out a rehabilitation plan and then undertake demolitions. But we are stuck in a sea of legal technicalities, where one HC judgement calls for immediate demolition, and another for ‘working towards’ a rehabilitation plan. Meanwhile, the residents have nowhere to go.” Behanbox has written to the ASI asking if proper rehabilitation processes were followed. The copy will be updated when we receive a response.

It is important to note here that the ASI presented the residents of Tughlakabad with an eviction and demolition notice on January 11. Soon the residents, with the help of Mazdoor Awaz Sangharsh Samiti, moved the Delhi High Court seeking proper rehabilitation of those who will be displaced by the evictions. The recent court order dated April 18 has observed that the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) can provide the appropriate shelter home that can house the displaced residents of Tughlaqabad. However, the final decision will only take place at the next hearing that is scheduled for August 2, 2023. As of now, the residents of Tughlakabad have neither been provided shelter nor rehabilitation.

High Rents, Safety, Education

Renu (47) has been a resident of Tughlakabad for the past 10 years but with her home demolished she has no option but to seek rented accommodation in the area. “The rents have skyrocketed. For a one-room flat, we are paying Rs 8000,” she says.

Women like Suman, and Pinki too, who are employed as domestic workers in CR Park’s affluent pockets, are paying rents that are no less than Rs 9000-10000 for a room. Electricity rates are equally exorbitant, with landlords charging women Rs 8-9 per unit for electricity. “I cannot even afford it,” says a despondent Pinki. “I barely make 10,000, all my life’s savings were put into building the house. How can I survive now?” Even the prices of general utilities have risen. Bottled water, otherwise priced at Rs. 10, is now Rs. 20 in Tughlaqabad’s Churaiyya Mohalla.

Some of those who have lost their homes have built makeshift tents or jhuggis and jhopdis. However, women remain apprehensive about their own safety as well as that of their daughters. “There have been incidences of sexual harassment of young girls in the vicinity. I too have a daughter. I cannot afford to live on rent but I have to get a flat. The whole area here is a jungle. What if someone comes and makes us unconscious? What if something happens to my daughter? There is no light, water, nothing here,” says Renu.

Residents tell us that families with more than three children are being denied rented accommodation. Landlords say that “more kids mean more ruckus”. Ranju Devi (35), who has four daughters and two disabled sons, has nowhere to go. “How will I stay in this jhuggi jungle with four young girls? We came here because there is a school and a dispensary here. But everything is over now,” she says.

The demolitions have also affected several school-going girls in the area. Muskan (13) says all her books are under the rubble. “I haven’t been to school for the past two weeks,” she says. Anu, a Common University Entrance Test (CUET) aspirant, will not be able to take the exam this year as all her books are under the rubble.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.