[Readmelater]

Why A Workers’ Rights Activist Has Jumped Into The Electoral Fray

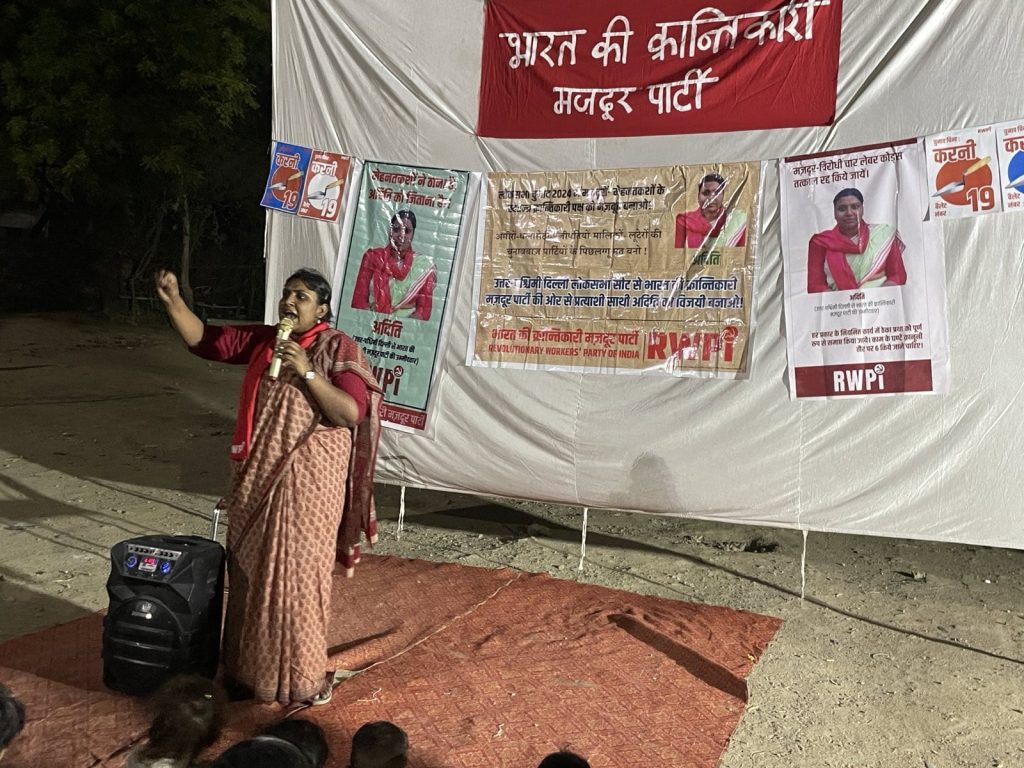

Aditi, a member of the Revolutionary Workers’ Party of India, has contested elections multiple times at both local and national levels but has never won. She says that winning was never the point

Aditi, a member of the Revolutionary Workers’ Party of India, is contesting elections from Delhi’s North West constituency/Ankita Dhar

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.