Why Women In Maharashtra Are Agitated About Ration-To-Cash Switch

Ration cardholders in various parts of Maharashtra are complaining that they are being denied food grains even before cash transfers have been made to their bank accounts

- Priyanka Tupe

Maharashtra’s pilot project for replacing subsidised rations with cash transfers has drawn the ire of beneficiaries, food rights activists and social organisations for patchy implementation and lack of transparency in how the transition is being managed, shows a Behanbox investigation.

In 2018, Maharashtra launched a limited pilot project to launch direct benefit transfers (DBT) in the state’s public distribution system (PDS) in two areas of Mumbai and one in Thane. Even while this move was being opposed by beneficiaries and food security advocates, a Februrary 2023 government notification declared that a DBT of Rs 150 would replace rations for families of farmers who died by suicide in 14 districts of the Marathwada and Vidarbha region.

The scheme is being implemented chaotically, without providing any prior information to beneficiaries, and this is leading to anxiety and resentment, show our interviews. Women complained that their family’s rations have been abruptly stopped, without any notice, and that ration shopkeepers have told them to wait for rations being distributed when it will start by the higher authorities in the PDS.

We spoke to 11 families that are survivors of farm suicides in Beed and Parbhani districts – few knew of the scheme and no one is receiving any cash transfer. Vidya Mhaske of Palwan village in Beed said she has heard of the scheme but is yet to get the money in her bank.

“The sarpanch, who oversees welfare schemes implementation, asked me to submit my saatbara (documentation for agriculture landholding) to receive Rs 150 in a bank account. But how can I submit my saatbara just like that? My ration has been stopped for a year and the rationwala said submit your documents like Aadhaar card, PAN card and so on online. I did that but got neither ration grains nor money,” said Mhaske.

Jyoti Shelke, 36, was widowed six years ago when her husband, a farmer, Ganesh Shelke, died by suicide. She has an acre of farmland entirely reliant on monsoon, and when drought hits, she works on daily wage work at neighbouring farms for Rs 200 a day. She also gets Rs 1000 a month under the Sanjay Gandhi Niradhar Yojana, collaborative state-Centre scheme for single women, and some financial support from her father.

For some time now Shelke has not been able to avail of her PDS allocation and it has become a struggle to feed her two children. “At the village ration shop they tell me: “Tumcha ration varunch band zalay, tumhi Aadhaar card, utpannacha dakhla aanun dya, suru hoil (your ration has been stopped by higher authorities. Submit your Aadhaar card, income certificate and it will be restarted). I did that and still I don’t get ration or cash transfer. Now they say it will take two-three months more,” said Shelke, who also lives in Palwan.

Two years ago, Shelke participated in a protest march in 2021 along with Ekal Mahila Sanghathana (single women’s collective) Beed, for not getting subsidised food grains at PDS shops, but she cannot afford to skip daily wage work often so she stopped going for the agitation. Shelke is not aware that she is entitled to the Maharashtra scheme for families of farmers who died by suicide.

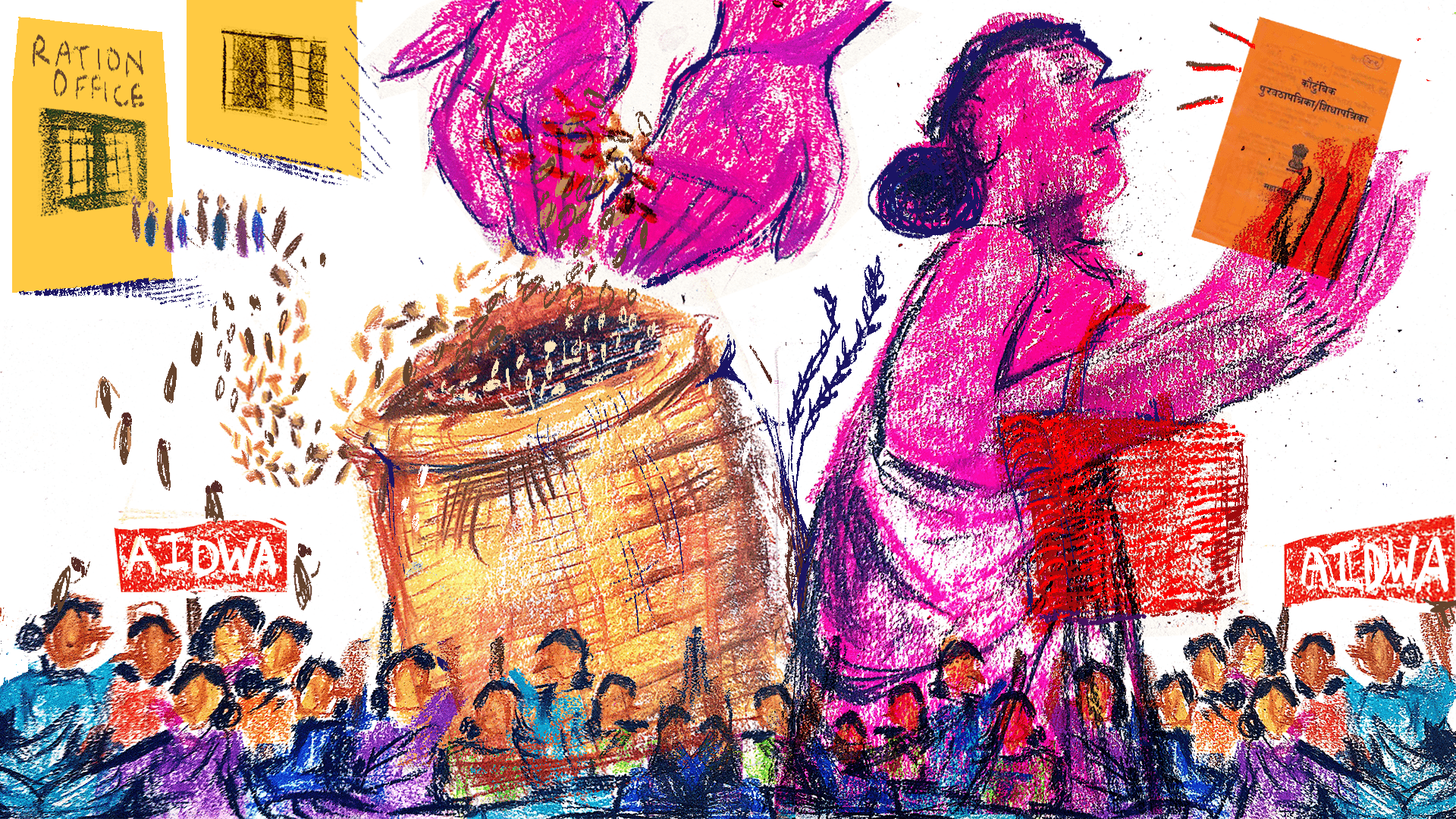

There have been protests across Maharashtra in Mumbai, Thane, Parbhani, Aurangabad led by multiple organisations. Beneficiaries alleged that DBT switch is being implemented in a stealthy manner – several women from eastern Mumbai’s Maharashtra Nagar and Samata Nagar complained that “private agents” are collecting their bank and identity details with clearly explaining why this is being done. They fear that this is a step towards total transition to DBT without seeking their consent.

Behanbox reached out to the secretary of the food and civil supplies department, Sumant Bhange, to find his response to these issues but he declined and directed us to the state’s Directorate General of Information and Public Relations.

The much-debated cash transfer system was first introduced in India in 2013 with a view to plugging the many leaks in the delivery of subsidies. It now covers some of the most critical schemes across ministries, among them the LPG and fertiliser subsidies, Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), National Social Assistance Programme (NSAP), Scholarship Scheme, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana – Gramin.

In 2015, the government notified “the cash for food subsidies” rule to cut down the huge physical movement of foodgrains across the country, give consumers autonomy and reduce leakages. States were left free to introduce the switch by initially starting limited pilot projects. Pilot projects began in union territories such as Chandigarh and Puducherry and Dadra Nagar Haveli and then spread to states. Today there are pilot projects being run in Maharashtra, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Jharkhand. There have been multiple complaints on glitches in the system (here, here and here) and Puducherry has sought a return to the ration system.

Economists and activists who support the DBT in other fields have been sceptical (here and here) about its effectiveness in replacing subsidised foodgrains. Jean Dreze, a welfare economist who has co-written Hunger and Public Action with Amartya Sen, is among them and he emphasised to Behanbox the importance of transparency and consultations in the transition.

“The problems that have arisen in Maharashtra sound like a replay of similar problems with earlier attempts to switch from the PDS to DBT in Rajasthan, Jharkhand, Puducherry and Chandigarh,” said the economist. “The switch is abruptly imposed, with little transparency and little attention to people’s hardships. All kinds of so-called teething problems emerge, often lasting for months if not years. No wonder the transition is unpopular.”

‘We Prefer Grains Over Cash’

The pilot project for families hit by farm suicides is currently operational in Aurangabad-(Chhatrapati Sambhaji Nagar), Jalna, Nanded, Beed, Osmanabad, Parbhani, Latur, Hingoli, Amravati, Washim, Akola, Buldhana, Yawatmal, and Wardha. But, as we pointed out earlier, beneficiaries in some pockets of Mumbai believe that the DBT experiment will soon be forced on everyone in the state.

Devi Subhash Jadhav, a resident of Maharashtra Nagar, Mumbai, explained why she prefers grains over cash. “With rising costs, we heavily rely on subsidised food grains. You should see the long queues for cheap rice and wheat at ration shops though it is poor quality. We need to pay Rs 160 to 200 for 1 kg of dal, Rs 150 for a 1 litre of cooking oil, and the price of a gas cylinder has increased beyond imagination and we have cut milk consumption. The government should not stop our ration at least. The Rs 150 transfer will get us a litre of oil only and then what do we eat?” she asks.

A 2019 Anna Adhikar Abbhiyan survey that included over 150 families who were part of the pilot DBT project of DBT in Mumbai showed that 72 % families feel that fair price ration shops are more easily accessible for them than banks and ATMs. Only 20% of women chose to switch to cash in place of foodgrains. However, 87.5% women said they cannot purchase 1 kg of foodgrain from the market with the Rs 22.5 given to them under DBT (in Mumbai under the pilot project in Mahalaxmi and Colaba area).

The women Behanbox interviewed said they are intimidated by the banking system while they find it easy to deal with the local ration shop. One of the most common critiques of the DBT was that it is mostly men who hold bank accounts and their normal spending habit does not prioritise the family’s most basic needs. Even where women hold accounts, they are actually operated by the men of the family.

“The men will withdraw the money and there is no guarantee that they will bring groceries for our children. Men’s priorities are different, they spend money on alcohol, drugs,” said Malini Rajbhar, a resident of Maharashtra Nagar, Mankhurd.

Vidhya Mhaske said there is no ATM in her village, she has to go to the Beed for withdrawing money which costs her total two hours of commute and Rs 50 for a shared auto rickshaw, as frequency of state transport buses is also very low at her village.

Devibai Chavhan, a domestic worker from Mankhurd in eastern Mumbai, is heavily reliant on PDS and cynical about the implementation of DBT. In Mankhurd’s Maharashtra Nagar and Samta Nagar most women are domestic workers and often denied ration because they cannot match the mandatory biometric thumb impression because their chores like cleaning dishes and washing clothes everyday change the thumb impact, she said.

“Ration dukandar doesn’t give us ration in such cases, and then we have to send our children for their thumb impression. If the current distribution system has these difficulties, why would we opt for DBT? Most women in our area don’t even have bank accounts,” she said.

Even in places where DBT has been introduced on an experimental basis, the implementation has been ad hoc, said Ulka Mahajan, an activist with Sarvahara Jan aandolan and convener of the Anna Adhikar Abhiyan. “In some parts of Vidarabha and Marathwada people get DBT, elsewhere people don’t get DBT but just foodgrains and in some areas they get neither DBT nor foodgrains,” she said.

There is another reason why farming collectives have opposed cash for grains. “Under it, the government doesn’t have to procure food grains and this means farmers will not get a minimum support price. Even today the central government has stopped the FCI (Food corporation of India) from buying (procurement) of food grains from the states like Punjab, Haryana which are highly agro productive,” said Rajan Kshirsagar, general secretary of Maharashtra Rajya Kisan Sabha, that organised protests in drought-hit Parbhani.

‘Why Are They Collecting Our Bank Details?’

Aruna Jagganth Gawade, 43 has complained several times to her ration shopkeeper in Maharashtra Nagar area in eastern Mumbai’s Mankhurd, about not getting provisions. He told her to visit a rationing office.

“After visiting our regional rationing office in Shivaji Nagar, I gave in all the documents – Aadhaar card, LPG passbook, bank account details – but I still didn’t get any ration. The rationing office has no answers to my questions. Why ask for my bank passbook details? Are they going to start cash transfers and when? What am I supposed to eat till then?” asks Gawande. “DBT is not going to help me because of rising prices. I will not get rice and wheat for Rs 2-3 a kg in the market as I do under PDS.”

A PDS official, who spoke to us on conditions of anonymity, said the DBT drive has been on since 2018 in Mumbai. “The rationing department selected two shops in each area. We were asked by higher officials to get information about 25 random RCMS numbers (provided to each ration card holder). We would then contact ration shops and ask them to stop providing foodgrains to the people whose numbers are given to us and give us the data on these beneficiaries – details of their Aadhaar cards, LPG passbook, bank passbook and so on. We have no idea how these [RMCS] numbers are selected.”

The officer said that the Maharashtra government had hired a private agency to collect the banking details of PDS beneficiaries for the switch to DBT. The agency’s personnel then started visiting the homes of beneficiaries and ration shopkeepers without the knowledge or approval of the rationing department, he alleged.

“We were also not informed about this by the higher authorities. It is when people refused to cooperate with the private agency personnel that authorities asked us to ensure cooperation. A meeting was called with this agency at the Office of the Controller of Rationing & Director of Civil Supplies at Churchgate. All the rationing officers in Mumbai were invited and told to cooperate with the agency staff, help them gain the trust of the people, and get their bank details,” he said.

Behanbox could not independently verify this information and reached out to the state’ food and civil supplies minister, Chhagan Bhujbal last month. He denied the hiring of a private firm by the government to facilitate the transition to the DBT mode.

“We will look into the issues if there are specific complaints of DBT not received in accounts. Also the government will think about increasing the amount given per person as DBT,” Bhujbal said. The minister also said that there were no public consultations held prior to the enactment of DBT in 14 districts of the Maharashtra for the families hit by farm suicides.

Last month Sona Gyanprakash Shrama, 24 a young domestic worker from Maharashtra Nagar, tried to open an account at the local State Bank of India but was told that even for a zero balance account, she was asked to pay/deposit Rs 1000 in the bank. Only then would she get an ATM card and a bank passbook. “Without Rs 1000 I can open a free account but I won’t get an ATM card. Which means I need to go to the bank every time to withdraw money for any welfare scheme. Visiting a bank costs me Rs 50 per trip and 2-3 hours of the day in travel and in a bank queue. What is the use then of a cash benefit transfer scheme? Instead of this whole exhausting DBT exercise, it is very easy to get foodgrains from the ration shop right next to my galli,” said Sharma.

At least 73% women in Maharashtra have bank accounts, as per National Family Health Survey – 5 but there is no data on the number of women actually accessing banks and ATMs.

Food Security And Women

Food security activists like Ulka Mahajan pointed out that women ensure the food security of families and DBT could undo this because a significant number of women don’t have access to bank accounts. “Dalit, Muslim, tribal and landless farm labourers will be exposed to more vulnerabilities because they don’t own enough agricultural lands to ensure their basic food security,” said Mahajan. “Women from marginalised communities will have an extra burden of caregiving in DBT, migrating women don’t have easy access to markets. This will impact women’s health and contribute to malnutrition in children as well. The recent hunger index shows, India is ranked 111, worse than its position in the last hunger index.”

The NFHS -5 shows that 35% children under 5 years of age in Maharashtra are stunted, 26% wasted, 1 % severely so and 36% are underweight. There is a direct connection between multidimensional poverty, nutrition and malnutrition, Savita Kulkarni, professor of Gokhale Institute of Economic and Political Science, who spoke to Behanbox on how bad access to food and nutrition was a big factor in the infant and maternal deaths for its story reported last month from Maharashtra.

Women deprived of nutrition suffer from various health issues, for instance NFHS-5 shows 20.8% of women have a body mass index below normal in Maharashtra and 54.2% of women are anaemic from the age 15 to 49. Upto 57.2% of women are anaemic from the age between 15 to 19 years and food activists have also expressed concern about the possibility that the number of anaemic women would rise if they are exposed to food scarcity, which is also compounded by rising unemployment during deadliest pandemic like covid, rising inflation and drought.

Activists also said they worried that the DBT push would dilute the National Food Security Act -2013 and destroy the legal entitlement of people to food security. The NFSA legally entitled up to 75% of rural and 50 % of Indian population for food security. Around 800 million people have access to highly subsidised food grains.

Rekha Deshpande of AIDWA, which has protested against DBT at Mumbai’s Azad Maidan in September drawing 5000 people from Mumbai, Thane, Raigad, Palghar, said women will lose the most from the transition. “Once the foodgrain distribution system goes totally out of the government’s hand, there will be no control over prices in the free market. The gas subsidy has proved this. Ultimately women will suffer and those in the margins,” she said.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.