Women Waste Pickers Jeopardise Their Lives For As Little As Rs 100 A Day

In July, a woman rag picker died as her foot caught in a waste truck during a desperate scramble to find valuable scrap. Her story reveals the highly hazardous conditions in which waste pickers work for a pittance

- Priyanka Tupe

“My sister meant everything to me. She was my best friend; we would chat, go shopping together. We had planned to go to Ajmer Sharif this Muharram, but that was not meant to happen,” says Sameena Khan, eyes numb with pain. She points to her niece, Khushboo, sitting with her at their home in Rafiq Nagar, in eastern Mumbai’s Govandi area. “Is bachhi ke sar ke upar se maa ka saya hata, ek toh baap bhi nahi hai (This child’s father had gone missing and now she is motherless too.)”

Khushboo, 13, dressed in a purple salwar suit, sits quietly, staring into nothingness. Her khaala (maternal aunt) is her only family now. Her mother, Shahnaz alias Haseena Khan, 30, died early last month in an accident at the Deonar dumping ground in eastern Mumbai.

Shahnaz was a waste picker, and the 120-acre Deonar landfill, nearly 2 km from her home, was her workplace. Every day she would be there at 8.30 am when the waste trucks of the Mumbai municipal corporation started arriving to unload the city’s waste. She, like many other waste pickers, would rush to the trucks for valuable pickings like plastic, glass bottles and metal goods that could fetch them a decent price from scrap dealers.

At around 10 am, when Shahnaz ran towards an incoming truck, her gumboots got caught in a wheel. Though she struggled to free herself, the driver, who could not see her, drove straight into her. Severely injured, Shahnaz was rushed to the state-run Rajawadi Hospital in Ghatkopar but did not survive. (Behanbox could not access the post-mortem report and confirm the exact cause of death but her family spoke of excessive blood loss.) An FIR was lodged at Shivajinagar Police station in Mumbai on July 7 against the driver, Faizan Mansoor Shaikh, 24, under Sections 279, 304-A (causing death by negligence, not amounting to culpable homicide) of the IPC and Motor Vehicle Act 134A, 134B. (BehanBox has access to the FIR.)

The Khan family is still in mourning and struggling to deal with the loss of its sole breadwinner. Khushboo is a Class 8 student and she needs Rs 12 a day for her school commute to Ghatkopar. Her grandparents are aged and her aunt has four children to care for with the Rs 15,000 that her husband brings home as a truck driver. Khusbhoo’s hopes of a school education are now pinned on an NGO that works with waste pickers in the area, the Stree Mukti Sanghatana.

Shahnaz Khan’s tragedy is not an isolated one. In the absence of official data, various sources estimate the number of waste pickers in India at anywhere between 4 million to 5 million. Nearly 80% of them are women except in some north Indian states, estimates Jyoti Mhapasekar of Stree Mukti Sanghatana in her book Kachra Navhe Sampatti (waste is wealth). They all belong to Dalit and Muslim communities and work under extremely hazardous and unhygienic conditions to earn just Rs 50-300 a day. And if they work at dumping grounds like Deonar, the dangers multiply – pollution, toxic gases and frequent fires. But there are no official records of the injuries or deaths caused by these.

“It is hard to get data on accidents and deaths at dumping grounds. The Deonar grounds are a prohibited zone and the waste pickers presence is considered illegal although waste pickers have been working there for more than 100 years. Since the 2016 fires, the waste pickers entry here is prohibited and they are beaten up and chased out. There is no safety in their work although they help the city in waste management,” says Saumya Roy, journalist and author of The Mountain Tales: Love and Loss in the Municipality of Castaway Belongings.

We interviewed several waste pickers in Mumbai, Pune, Aurangabad and Kolhapur, who reported that dumping grounds, community bins and waste collections areas are highly unsafe workspaces. These are, in fact, not considered workspaces at all, and certainly not for women. Women who take on these work do so in inhuman conditions – with no access to toilets, drinking water, shelter or rest area and the constant threat of abuse and violence in the isolated and unlit corners of cities.

Waste pickers are not categorically recognised as informal sector workers in India’s 2016 National Policy for women. It only includes construction workers, domestic workers (referred to as domestic ‘servants’ in the official policy document), and brick kiln workers in this category. Maharashtra’s latest 2022 policy draft for women also does not recognise waste pickers as informal workers so that their interests can be safeguarded. (Domestic workers, construction workers, brick kiln workers, mining workers, small traders, street vendors, hawkers, folk artisans, transgender sexworkers, bar dancers are recognised in the ‘Gender and Informal Labour’ section of the draft.) There are no policies in India, we found that exclusively deal with waste pickers and specifically women waste pickers.

Millions Exposed To High Levels Of Hazards

Shahnaz’s family recalls her as a loving, sprightly, helpful woman who was close to her community. “Meri bahan sabki madad karti thi, kisi ko bhi jarurat padne pe paise deti thi. Bahut khush rahti thi vo, usko sajna sawarna acha lagta tha, maas macchi banana acha lagta tha. Gosht vagehra lati thi vo kabhi kabhi, to vo saf karke deti, mai banati thi (My sister helped everyone. She was always cheerful, loved to dress up, and loved to cook meat and fish. If she bought mutton, she would clean it and I would cook it),” says Sameena.

Shahnaz’s friends Shashikala and Ameena, also waste pickers, worked with her till the day she died. Don’t they now worry for their own safety? “Kay karta? Potasathi karavach lagata, navara tar kay kam karat nahi (What to do? We have no option, my husband earns nothing),” says Sashikala.

The hazards increase several times over for those who sort through waste at night, in pitch dark, in dumps full of filth, reptiles, rodents and sharp objects. “Sometimes we work late at night because there is no guarantee of finding saleable waste material during the day. Many of us work barefoot or use broken, discarded footwear. There is constant fear of snakes, scorpions, rats, dogs while we work,” says Savitri Bagul, a waste picker from Aurangabad. Another waste picker spoke of fears of physical abuse and sexual harassment by “charsi, gardullas (men who consume drugs)” who sit around in badly lit corners of dumping grounds.

Medical waste increases the risks of infections and injuries. There are needles and syringes that hurt them, used condoms, used sanitary napkins and diapers that raise the risk of infections. Also, those living around landfills often use the grounds for defecation that makes for highly unhygienic work conditions.

Aasha Doke, a waste picker from Aurangabad and a union leader of Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat, says the work is marked by acute desperation. “We don’t get much solid waste nowadays because the Aurangabad municipality now provides ghantagadis, waste collection trucks that collect from community bins. The municipality gives collection contracts to its own people and they in turn appoint drivers and waste collectors for these trucks. These people don’t allow us to collect waste. We have been demanding jobs at these positions for our people.”

The economic conditions of waste pickers vary from city to city. “Those in urban areas get the more saleable items from solid waste because there is a lot more waste generation in cities than in rural areas,” Nikita Patil of The Alliance of Indian Waste Pickers told Behanbox. Activists of Stree Mukti Sanghatana also observe that the urban upper middle class generates more waste than any other section of the society.

State Negligence, Apathy

Cities in Maharashtra have different strategies for solid waste disposal and this decides the lives of its waste picking community. Mumbai and Pune, for instance, have landfills. But Pune has a different mechanism as its municipal corporation has partnered with a waste pickers collective, ‘SWACH’, that collects segregated dry and wet waste from every home.

The state’s annual report on solid waste management rules, the latest of which was published in 2016, says that on average 80-90 % of waste is segregated and 60-70 % is processed in Maharashtra. However, that is an inflated figure, Behanbox has learnt from activists.

The Bombay High court ordered the closure of the Deonar dumping yard a few years ago but the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation or BMC sought extensions time and again. There are similar conditions at the Mulund and Kanjurmarg dumping yards. The BMC has yet to start a waste-to-energy project which was proposed and the Bombay high court frequently seeks a status report on it. Who will work on these projects? What will they mean for waste pickers? These questions remained unanswered.

There is no government effort to protect the lives or livelihoods of waste pickers. A 1995 report of the Bajaj Committee on urban solid waste management in India has recommended that ragpickers be included in solid waste management, at both collection and segregation levels. In Maharashtra, only Pune city has implemented this strategy successfully.

As we said earlier, the Pune Municipal Corporation has entered an official partnership with the Kagad Kach Patra Kashtakari Panchayat’s (KKPKP) collective of waste pickers, SWACH, in 2008 and this continues till date. Women pickers far outnumber men in KKPKP and under the system, segregated waste is collected directly from households. Non-recyclable solid waste is further segregated for sale, while the organic and non-recyclable waste is dropped off at PMC’s ‘feeder points,’ from where it is sent to landfills. This model has created better work conditions for women waste pickers in terms of work and pay, safety measures and unionised support. Waste pickers who are members of the KKPKP and work with the Pune Municipal Corporation now get Rs 75 monthly from each household. So a waste picker who works for 200 households earns Rs 15,000 a month. Those who collect recyclable waste and sell it in a personal capacity do not get a fixed or a minimum wage.

But this is not the case in other districts in Maharashtra.

Maharashtra’s policy for women 2013 underlined the need for effective distribution of ration cards to all informal women workers. But after a decade, in 2023, waste pickers are still struggling for ration cards.

“We have been demanding ration cards constantly, and we marched to the collector’s office at Aurangabad with our demand charter recently. The collector told us to get some identity proofs from our villages. We are migrants, hardly earning Rs 200 a day. Where do we go and which money should we spend for this?” asks Aasha Doke.

Behanbox contacted Aditi Tatkare, the minister of women and child development, to understand the steps being taken to protect the lives and livelihoods of women who work at dumping centres. Despite several attempts of calls, messages and a questionnaire sent, we have yet to receive a reply. This copy will be updated when we receive a response. Behanbox also contacted Rupali Chakankar, chair of the Maharashtra State’s Women commission, to raise similar questions. We will update this story when we get a response from her.

Lowest In The Waste Business Hierarchy

Waste management in India is reportedly a $ 14-billion business. But none of this wealth is visible in the lives of those who occupy the industry’s lowest rung.

Cities produce 131,000 tonnes of waste everyday, of which 60 % is picked up daily, according to the Central Pollution Control Board’s report published in 2013. Up to 40% of this waste remains unpicked and unprocessed needing lakhs of square kilometres that turn into mountainous landfills – the Deonar dumping yard for instance has reached the height of an 18-storey tower.

Waste pickers play a crucial role in recycling material, reducing the extent of ocean and landfill waste. But for all this, they earn anywhere between Rs 100 and Rs 300 a day, as we said earlier. In smaller cities, such as Kolhapur and Aurangabad, they earn between Rs 50 and 200 a day. There are also days when they earn nothing. The average monthly income of women waste pickers is less than Rs 10,000, we found.

Consider the supply chain in waste management – the waste pickers are at the absolute bottom of it. Kaatewalas (retail scrap dealers), all of them men, earn much more. We tried interviewing some but they refused to divulge any details of their earnings. But an activist who did not wish to be named said that wholesale scrap dealers, recycling companies, and waste management companies earn way more than the waste pickers who are the most critical part of the process. Those who stand at the top of this hierarchy also belong to dominant castes and classes.

Dalmia Polypro is a waste management company with plastic recycling plants at Vapi and Silvassa in Gujarat, and it mostly recycles plastic waste collected from Mumbai. Its earnings exceed Rs 50 crore annually, as per a senior company official who did not wish to be named. The company pays women workers at its segregation centres in Mumbai Rs 400 a day as wages. Men get Rs 500-600 for this and the additional tasks they perform like loading and unloading vehicles. “Women can’t do the heavy tasks, so they are getting paid less than men,” said an official.

Debartho Banerjee, a director and co-founder of Sampurna Earth, a waste management company, pointed out that such enterprises do not train women for better opportunities. “We try to include a maximum number of women in the workforce and we are thinking of diversifying their roles. We also provide them better work conditions – work at segregation centres and not dumping yards and safety kits. We ensure they get the documents needed to avail government social security schemes,” he says.

Gated housing societies are also becoming increasingly intolerant of waste pickers, alleging that they are criminal elements. “People don’t socialise with us, don’t talk to us because they think we stink all the time. They abuse us and shut colony gates on our face. Leave aside sorting through their waste we cannot even enter their colonies,” says Mangal Khadake, a waste picker from Aurangabad’s Indira Nagar. Police often stop women waste pickers from roaming around and collecting solid waste, thinking they are the ‘potential’ thieves, we were told. Waste pickers are also being blamed for fires breaking out at dumping yards, activists working in the sector tell us.

‘If I Rest, Who Will Feed My Children?

At age 38, Sashikala Aarakh, a Mumbai waste picker is already a grandmother. She was married off at age 13 and soon after became a mother of two. She migrated to Mumbai from Aurangabad in search of work. Her husband is an alcoholic who does not work and she has been the sole breadwinner for the family. She has dealt with several kinds of violence in her life, she says.

Savitri Bagul lives in Aurangabad’s Indira Nagar slums and her life has been equally challenging. Her parents migrated from the Selu-Manwat area in Parbhani to Aurangabad in search of a living. Her family has 3-4 acres of non-irrigated land but it yields little. She was married off when at age 14 and then abandoned by her husband after she had two sons.

Bagul works over 8-10 hours everyday but barely makes Rs 150-200 a day. She is up at 5 am usually and out to collect waste between 5.30 am and 6 am without any breakfast. She walks nearly 10 km everyday to the community bins around Indira Nagar and the waste she carries for sale often weighs 40-50 kg. After she sorts through the waste, she goes home for lunch around 12.30 PM, a meal of mostly rice with watery dal or curry. Vegetables and roti are a luxury reserved for festivals. She then segregates her waste collection, a task that can take up to two hours, and takes it to a retail scrap dealer in the neighbourhood.

It is usually 4-5 pm when she returns home, having spent half her earnings on groceries. Her small savings go towards paying the monthly rent of Rs 3000. She lost most of her savings recently when she had to have a hysterectomy. “I sold whatever gold I had and spent Rs 16,000. I used to be sick frequently because of the fibroid tumours but if I sat at home who would’ve fed my children,” she says.

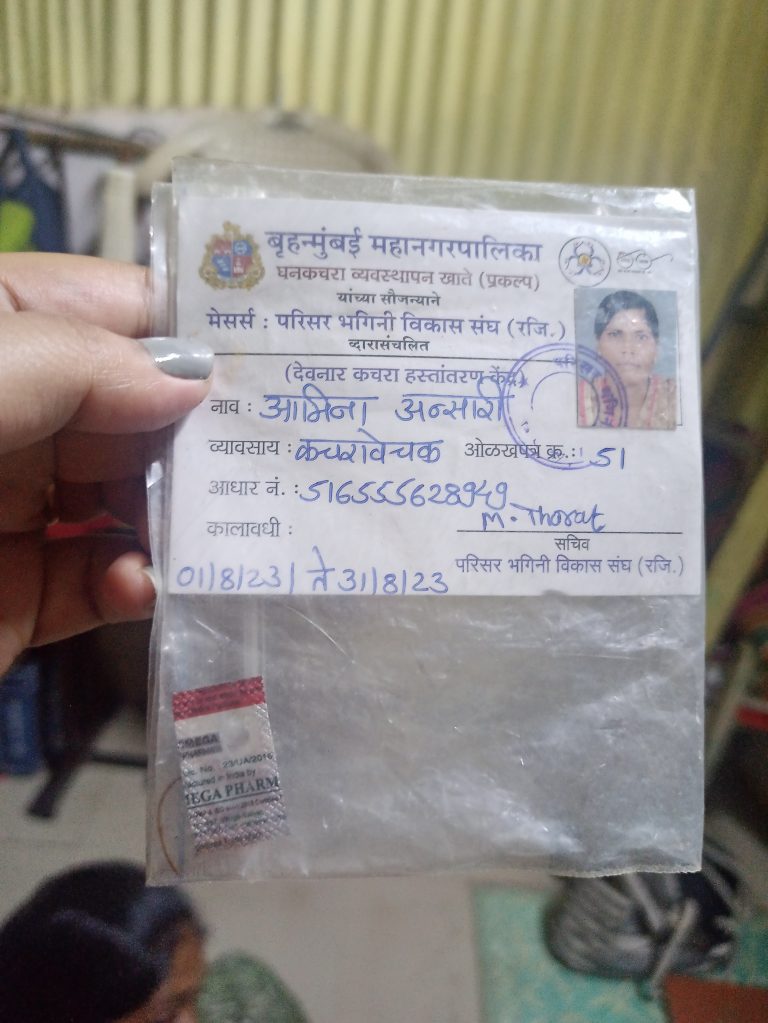

Ameena Ansari, who works at Deonar dumping ground, carries a Diclogem, a painkiller, tucked into her waste picker ID card, issued by the Stree Mukti Sanghatana. “I suffer from frequent headaches so I always keep one tablet with me. I also share it with other women in need. We can’t afford to rest when we are ill. Who will feed our children?” she asks.

Mangal Khadake migrated to Aurngabad from Jalna district in the drought prone Marathwada region. She left her abusive husband five years ago. She was unable to conceive and the stress that this caused was worsened by her husband’s alcoholism and ensuing violent behaviour. “He consumed alcohol everyday, I couldn’t bear it and finally left him,” she says.

Many women waste pickers narrated stories of early marriage, teen motherhood, spousal violence or adultery. Poverty was a constant factor in many of these stories and most women complained of husbands blowing up their earnings on alcohol and drugs.

“The poverty is acute. I saw women in these communities go to great lengths to support their children. Some had tried to be surrogate mothers while others had been subjects for medical trials to earn a living.” says author Saumya Roy.

Patil of the Alliance of Indian Waste Pickers recently organised a gender training programme in Kolhapur with a partner organisation, Avanti. “Female waste pickers are mostly uneducated or barely literate and vulnerable. Many of them fast two-three days a week as a religious practice though it takes a toll on their health. It was important to create awareness among them. They said the programme offered them a different outlook – for the first time in their lives,” says Patil.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.