Tired of Roaming About At Home And In The World

The country is partitioned. India is independent. Crowds of people are pouring in from East Pakistan—from Jessore, Khulna, Barisal, Faridpur, via Kushtia and the border at Darshana. Some go towards Bongaon. After they cross the border, they see Gede railway station. They are immigrants, ‘refugees’, in formal English terminology. They’re a motley, chaotic lot. The children, the elderly, the young are heavily loaded with jute bags balanced on their heads and waists. Many are seated in the train. The comparatively affluent ones have some tin trunks along with their jute bags. Some have brought their pet cats with them. Others are carrying arum saplings. After an hour’s journey they get down from the steam-engine train. Coo-jhik-jhik. The driver has been throwing spadesful of coal non-stop into the flaming fire. If the engine is in need of water, they take it from the long and fat pipe at large stations. The pipe is a very interesting thing. It has a circular wheel-like thing at one end. Climbing up to the top of the engine, the driver pulls the pipe close to himself. Then he unscrews the circular wheel over the netted opening of the engine and releases the water it needs. And at short intervals he throws spadesful of coal into the flames. When the guard sahib blows the whistle from the back of the train, the black queen again starts running with the coo-jhik- jhik noise. Now the black beauty has departed.

Seated on the bug-populated bench of the train, with her legs tucked under her, Bengi pisi stretches out her hand and says, ‘Nakkir ma, give me a pinch of gurho powder.’

The gurho is prepared by putting charred tobacco leaves and bits of burnt hay in an earthen sora and then ‘pasting’ it with an iron norha, a pestle. Lakshmi’s mother, Bengi pisi, Makhan’s mother and his junior grandmothers together prepare this gurho. As soon as their destination arrives, they all get down with the help of those who came here a month ago for a reconnaissance. They see a vast field full of reeds and thickets of grass.

Some people who have never been on a train before lean against each other as they get down at the station. Then, as instructed by the leaders, they start walking towards the reed- populated land beside the bil.

The bil is a favourite of theirs. The fish, nal, shaluk, ghechu from the bil, all are their food. Then, there is the jagli paddy, the traditional kind. Chingrhebhushi, the traditional paddy, makes very good quality hoorhoom. And chirhey, parched rice is prepared from gourkajal, another kind of traditional paddy.

When they were in their native land, these people spent most of the year on the island-like mounds surrounded by water. To go to another house, one could not do without a boat or donga. Over there, their work included fishing, sowing paddy, harvesting jute plants by diving repeatedly into the water and rowing tabure, the small water taxis.

‘O pisi, why do you weep?’ Samir asks Bengi pisi.

‘My heart is burning. Where have we come?’ Bengi pisi pushes her hand into her thick grey hair and scratches. She has a lot of lice in her hair. Samir knows it.

Until they build their separate houses, all the villagers cook and eat together in a common kitchen and eating area. This large ‘joint family’ gradually divides itself into smaller families beside the bil. The only consolation is that there is a bil at the stretch of a hand for everyone. Chhola, chickpea dal, cooks well if boiled in the water of this bil. Kanule’s mother, Dinabandhu’s mother and Shangale’s sister, his didi, collect water in brass pitchers. They prepare the watery fenabhat with reddish home-husked rice in earthen vessels in the clay oven. At breakfast time the mouth-watering aroma of the reddish fenabhat with boiled potato and brinjal stirs up one’s hunger. Fenabhat, from two measures of rice, is prepared in no time. As it cools it forms a thin skin on the surface. The separate lumps of rice automatically reach the mouth. As if they have been cut into pieces with a spoon.

Soteka is the seniormost person in the parha, the locality. The whole day he smokes his hookah and talks about bygone days, his native land and households there.

‘We used to eat so much fish and how tasty it was! Isn’t that right, Permotho?’

‘No matter what you say, there is a difference of heaven and hell between that country and this one. Can the water of the Madhumati and that of Andhar Bil be the same? Look at what the haat of Naldi was and what the one at Duttabiley is! It’s all luck. Now tell me, shall we go back if we are not rehabilitated? What’s your opinion, taoi?

Soteka replies, ‘Is it possible? What we’ve left is left forever.’

Soteka is a bachelor. He lives with his elder brother’s family. He has a long friendship with his boudi, his sister- in-law, Subhadra. Subhadra was married to Tarini khurho, his brother. At the time of the wedding, Subhadra was a girl of nine or ten. She could not walk properly if clad in a sari. One day she thought she couldn’t stay on in this family. She was in a dejected mood and missing her mother. So she packed up her clothes and ran away. There was a river in front of her and she plunged into the water and swam across. When she got to the other side, she met an old man. She covered her head and impersonated a certain Moti Miah and in this way she reached her parents’ house. This is her own version.

Subhadra has so many other stories. These are all chatam, the kind of bragging the old men are skilled at.

Subhadra’s son has an immoral character. One day she told us this story. Just before her son was born, she came out of her bath one day and saw her lascivious bhasur, her brother-in- law, and this is why her son has become as lascivious as him. Soteka has spent his whole life for Subhadra. He did not get married. When Tarini khurho discovered his wife’s extra marital affair with his brother, he vanished and never came back.

Soteka often talks to Permotho. They compare different foods, clothes, the weave of fabric and the air of the two countries. Things of the country left behind always win the best position. This nostalgia also haunts Bengi pisi, Laxmi’s mother, Subhadra and Makhan’s mother, as it does Soteka and Permotho. The women, with their ghomta, sari pallus pulled down to their noses, spend their days consuming gurho and talking of the past. Some stitch kantha quilts, others take a dhama, a basket, full of paddy and set off to husk it. They stitch the kantha at night, by gata, a shared system of work, working deep into the small hours. Their needles travel the path of Nakshikantha Maath and recount the art of the epic of Jasimuddin. Late at night they go back to their respective houses or sleep in the same bed till dawn.

Kanule’s mother, the bhagni of Sardar Moshai, is married to Sukhamoy. No one any longer knows the real name of this niece of Sardar Moshai. She was surely nobody’s mother at the time of her birth. Yet ‘mother’ is her identity. The people of the parha calls her Kanule’s ma and so does Sukhamoy. All the parha women are Mina’s ma, Sabi’s ma, Ashoke’s ma, Pagol’s ma— as if the mothers are ma right from their birth. The boys of the parha have names like Kanule, Shangale, Joongule, etc. No one knows their meanings.

Sukhamoy is a very energetic man. He is five feet tall. His body structure is very good. He has almost no relatives of his own. He stays with his brother’s widow. He is a man, an energetic and active groom who should not be missed. Kanule’s grandfather does not delay a bit. He marries his daughter off to him immediately.

The wedding gift includes only a brass pitcher on which the names of Sukhamoy and his wife are engraved. No one calls her by that name now, even her own mother addresses her as Kanule’s ma.

Offspring identify the mother. A tree is identified by its fruit. Sukhamoy has been suffering from a mild fever and cough for quite a long time. The fever does not leave him. Some suggest ‘Go to the gosain’s place.’ Others say, ‘Go to the hospital.’ Just before Kanule’s birth he goes to the gosain’s place and recovers. He is given some herbs that no one can remember now. But Kanule’s mother remembers: she was asked to grind durba grass into a paste and feed it to him with milk.

Desirous of her son-in-law’s recovery Sukhamoy’s mother-in-law arranges a puja, in honour of the goddess Subachani. The narrator is Subhadra. She is the person who tells the stories in all the Subachani pujas of the parha. Arrangements have been made by planting a kool, a jujube branch and placing before it a brass tumbler painted with oil and vermilion, with a tender, leafy twig from a mango tree on it. Beside it there lies a banana under a cane dhama. Persons who are not male are forbidden to eat this banana. Subhadra starts the story.

A certain woman who had no children lived in a forest near a village. One day there came the Old Shiva in disguise and he urinated there and left the place. A leafy data plant grew where he peed. The woman ate a curry prepared with that plant and thereafter she gave birth to a baby boy. Later, when he was grown, the boy was sentenced to imprisonment for killing a duck from the flock belonging to the king. The woman sat down and invoked the goddess Subachani. The goddess was pleased and blessed her with a boon. The boon brought the dead duck to life again. The banana that lies under the dhama basket symbolizes that duck. When it comes back to life it is to be thrown away. The boys pick it up and eat it. Then, when the duck re-joined its flock, the king married his daughter to the convicted man and built them a palace in the forest.

Such is the story of Subhadra. The puja ends with ululation and the women sprinkle drops of mustard oil on everyone’s head. All women whose husbands are alive are given vermilion, and the sacred food, prasad, is distributed all round. Vigorously chewing on betel leaves and nuts, people go back to their homes. The puja will restart early in the morning, before sunrise. After weddings or after recovering from an illness, all families perform this puja.

Permotho is puffing on his hookah. He comes to visit Sote khurho. Conversation starts, and sometimes there is chatam.

— Taoi, Sarkar Moshai is going to Dinajpur with some families. I don’t know if land is cheaper there.

— Perhaps.

Soteka draws a puff from the hookah.

— The eldest bhagney of Sardar Moshai is also going to Dandakaranya. Land will be distributed there, I’ve come to know. He’ll go to the Mana Camp. What will he live on there? The only thing that grows there is corn, nothing else. You’ve left one country and come to another, and again to leave this place! Excessive greed is never good. They’ll come back soon, I bet. See, if they don’t, then you can tell me I’m talking rubbish.

— It’s also necessary to wander and see what there is, to know what is available where. Does staying at one place provide one with a job? What will you eat if you don’t work? How will you feed your children? Lo, how feeble they’ve all become!

— The parha is going to be lonely, taoi. Only vacant houses will be left there. I don’t have a good feeling about it.

Permotho wipes his eyes.

— The houses of Chatak, Shangale and Gagan are all vacant. There are houses but no human beings. We came together here. Now if everybody leaves separately, won’t we become weak?

— We won’t have to fight against the Mocholmans, that needs strength. And that violence with sticks, lathikhela, has also stopped.

— O taoi, I forgot to tell you, there will be a rowing competition between the people of Gournagar and ours. Everyone is sharpening their choppers, the ramdas, for the battle. Pellad’s mother has rubbed the brass pitcher clean. It’s sparkling. Who knows who’ll win?

Soteka coughs loudly, a hacking cough, and hangs his hookah on the jute-stick wall.

Hurried preparations begin early in the morning the next day. Everyone is busy going back and forth from the shore of the bil. Food preparations are quickly done. Today is a festive day. A frisson of excitement runs through their hearts. They arrive, large vermilion marks on their foreheads, the beat of the kansi and the sound of ululation marking their steps, and they start the boats. Some move the ramda. A shining brass pitcher is tied over the boat. On the banks of the bil are raucous crowds of people from several villages around. Harindanga, Koikhali, Punditpur, Bhabanipur and

Garhapota, they surround the Andhar Bil and the Laxmi Bil. A canal connects the two. The war will begin soon. The red-eyed heroes with oars in their hands now show their muscle power. They row vigorously, as if in a frenzy. The oars splash and slap against the water, the men move to a silent, intense rhythm, accompanied by the beating of the kansi, the spectators shout and scream and urge them on. The boat makes it to the finish! The western parha suddenly falls silent, the eastern parha has won! What joy breaks out in the winning parha then! All of them happily receive their prize and go home.

A fight, kajiya, takes place between two groups. It’s against the people of Bhabanipur and their claim to Sukhamoy’s father-in-law’s land. They won’t let him occupy the land. They’ll reap the paddy by force. Two troops have gone to the front, with choppers and spears. Sukhamoy is his father- in-law’s only support. He wins the battle and returns home to find that Kanule’s mother has given birth to a baby girl. The womenfolk are ululating together. The husking room has been used as a labour room.

Surjyamani is the midwife. She brings some burnt paddy skins in a terracotta pot, a bata. She cuts the umbilical cord with a bamboo blade. The new mother stays in the husking room for six days. Sukhamoy’s father-in-law suggests Ranangini as a name for the baby girl. It is not accepted. Eventually she is named Sonali. She is very fair and Sukhamoy calls her Sonar Buchi, the golden blunt-nosed child. With the three-month baby in his lap the father roams about the entire parha, just as mendicant monks wander abegging with the idol of goddess Shitala in a small wooden box.

Even before Sonar Buchi grows up, a baby boy is born, and then he is followed by another girl. No, no more. But what can mere words do? Once again, a black bocha, a baby girl, is born, an extra burden to add to the existing one. Sukhamoy says, ‘No Shashti puja is necessary. We ’ll manage without it.’ So, without the puja, Mrinmoyee, the mother of Kanule moves from the labour room to the larger room. She searches far and wide for a proper name. As the baby is black, she is first named Kulthe. But at last, after much calculation, she becomes Kamalini. When calling out aloud to the baby the mother shouts, ‘O Kamal, Kamalini’. If the child does not respond, she says, ‘O Kulthe, will you answer or shall I come?’

A daughter of the earth, Kamal grows up. She stays in the lap of the eldest one or crawls around on the ground. Mrinmoyee does not even realize when she grows up and learns to wander through the jungles. The gardens nearby and far-off, the open fields, the bil, she misses nothing. When it is evening, she comes back after surveying the overgrown bushes behind the houses. She has neither the discipline of bathing nor of eating. There is an old woman called Subhadra. She has no sense of time, of appropriate or inappropriate times. She wanders with the girl in the northern and southern fields. The girl likes her. She follows her always. A bamboo basket with her, she follows the old woman to gather cowdung.

Subhadra is poor. She collects a few branches from someone’s garden, and some leaves from elsewhere and somehow manages to save on fuel. Kamalini is very attached to Subhadra, she grew up in her lap, so she follows her into the fields. Once they are done, they travel through Laxmi Bil and the eastern field and return home in the evening. How large the lumps of cowdung manure! The cattle drop the dung after eating grass. Sometimes they find dung that has been dropped by bullocks at the time of tilling the land, often in dry form. Two or three lumps dropped by bullocks fill the basket. Kamalini cannot carry the full basket, after a short distance she puts it down. Subhadra also picks up cowdung and fills her basket. The two friends of unequal ages talk so much. When they get home it is already evening. Sometimes when they go to the southern field, Kamalini says, ‘If it becomes evening today by the time we return home my ma will scold me.’

Subhadra scolds her, ‘Tut, you wench. Have I brought the evening out of my pocket? As soon as the basket be full, we’ll start walking.’

After the jute plants have been harvested and the land tilled, the roots of the plants come up. These gojas and the cowdung cakes are very good as firewood. When collecting these, Kamalini and Subhadra also pick up other things, the leaves of the creepers, Chhechisak, Kalmisak and Malanchasak, if they can find them. The ghonto, the vegetable curry, prepared with Chhechisak and the tiny prawns from the bil tastes so delicious that it seems to play a heavenly tune.

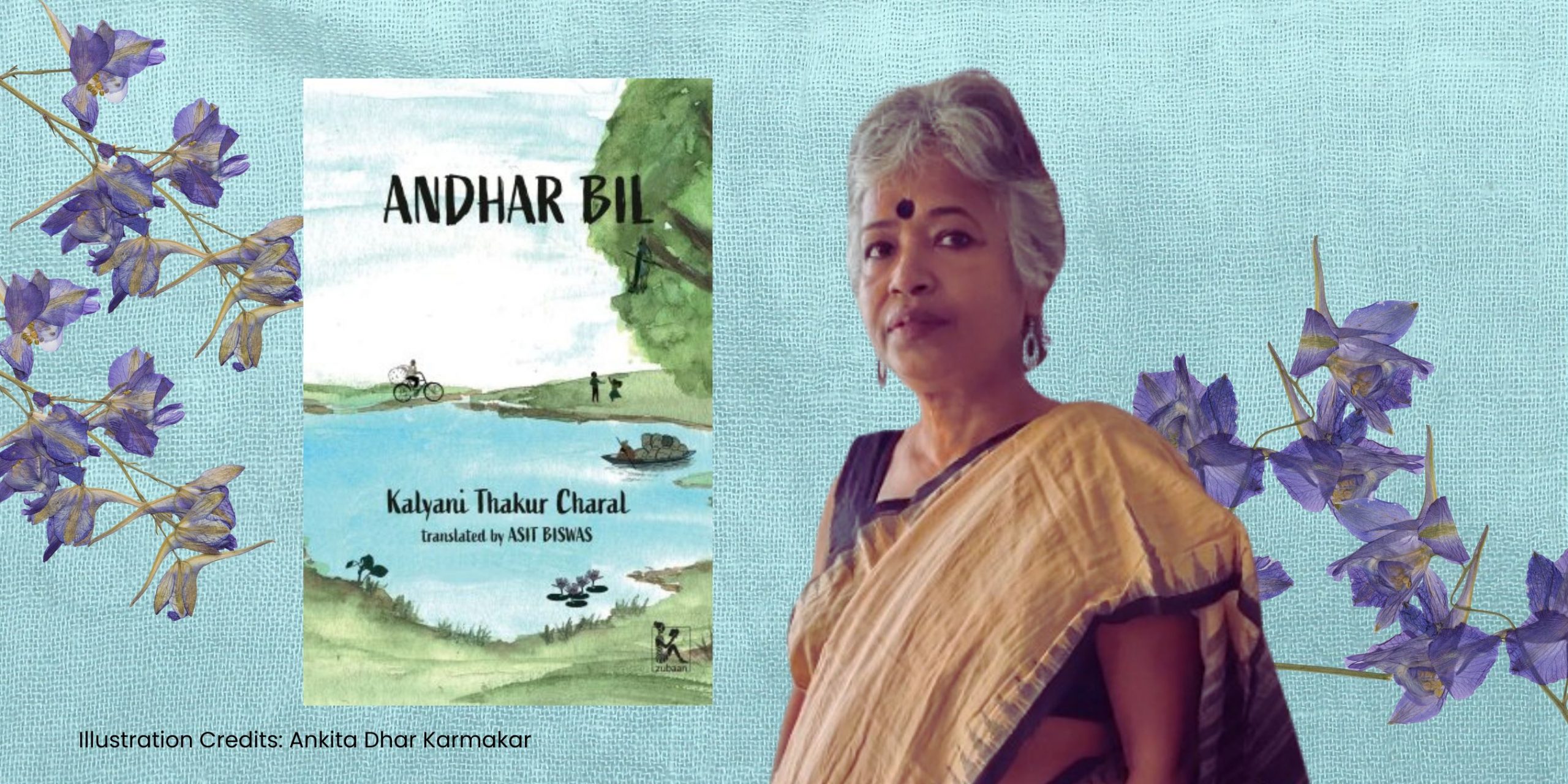

[ This is an excerpt from the book Andhar Bil and Some People by Kalyani Thakur Charal, translated by Asit Biswas and published by Zubaan Books.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.