Hijab Ban And The Politics Of Clothing In Contemporary India

Indian history is replete with biographical and regional details regarding spatial and sartorial separation of women from men

I probably belong to a tiny minority of Indians who studied in a school that didn’t have a uniform. This made us feel special; it also made life simpler as one could jump into whatever was at hand and run to school. For the most part we were an ill dressed and shabby lot, but that was perhaps par for the course for those who grew up in the 1960s and 70s. Yet, I have spent a large part of my life being told by friends that having a quite absurd, as it is patently clear that poor Indian children going to government schools wear uniforms made of very poor material whereas their wealthier counterparts going to private schools wear clothes that look stylish and almost designer made. Within schools itself, especially where the middle and upper middle classes send their children, students are marked by any number of differences. From bags, lunch boxes to other accessories like pencil cases, watches and now smart phones, the difference despite the attempt at sartorial uniformity is the reality. And such differences are just the tip of the iceberg. Interestingly enough, the Principal of our school during my years there, a Miss Sengupta, was once asked why we didn’t have a uniform. Her reply, which every ex-student can recite by heart was, ‘I want my students to be butterflies not soldiers.’ In today’s India she would have been termed an anti-national and chucked into jail for sedition.

Yet, what she said then goes to the heart of the hijab vs uniform controversy that rocked the southern Indian state of Karnataka during the months of March and April 2022. As was evident to anyone with a modicum of political intelligence, this was a row engineered by the Hindutva, or the Hindu right wing, in the Bharatiya Janta Party [henceforth, BJP] ruled state. With this, a non-issue becomes one that threatens the education of hijab-clad Muslim students in the affected educational institutions in Udupi (and in time, elsewhere). Any numbers of logical rebuttals are of no value here as this was cleverly turned into a question of upholding dress codes in schools. Additionally, with the hijab-clad students turning to the courts for legal redress, the question became not merely one of adhering to school dress code, but one of determining the very status of the hijab within Islam. The adherence to the principle of the school uniform, which until now didn’t seem to have been all that inflexible—after all the same hijab-clad students had been attending school/ pre- university college until now—has now acquired the status of an inviolable law. Likewise, the hijab, with its many meanings has, in this instance, been reduced to being an ambivalent marker, which can variously be interpreted as denoting Islam’s intransigence while at the same time not being “essentially Islamic” enough for it to merit protection under Indian law. The immediate provocation for such an outcome was the Muslim women students going to court, and arguing for the right to wear the hijab as the ‘right to freedom of conscience’ protected by Article 25 of the Indian Constitution. The court’s verdict, with its stress on determining “essential” Islam, is also symptomatic of a tendency within Indian judicial history where the courts interpret what is in essence a Constitutional question—in this case the right of Muslim women students to profess their religion—through a supposed analysis of the religious premises of the petitioners’ demand. In denying the students the right to wear the hijab to school, or pre-university, the court’s judgement did not restrict itself to the petition that asserted the students’ right to religion as enshrined under Article 25 but instead chose to deliberate on whether their idea of the hijab as part of an interpretation of religious practice was permissible under the law. Based on a hair-splitting distinction between ‘freedom of conscience’ and ‘religious expression,’ the court maintained that the hijab was merely an outward expression, and not an ‘essential religious practice’ in Islam. Furthermore, the judges decreed that the uniform promoted the ‘principles of secularism,’ but also went on to argue that as ‘discipline and decorum’ were prerequisites of public spaces such as schools, ‘reasonable restrictions’ could be applied to all other freedoms, such as what one chose to wear. In such a reading, the hijab is both non-secular as it is indisciplined and indecorous!

This becomes particularly relevant when historically there is the entire domain of “purdah nasheen” or veiled Hindu women across caste from north India, to Nambudiri Brahmin women in Kerala, whose strict veiling was enforced in order to maintain bodily purity. Such forms of sartorial, or other kinds, of veiling were symbolic of their modesty and decorousness. Consequently, the seclusion that they were expected to follow was designed to achieve such a goal. For large numbers of Hindu communities in north and eastern India that practice purdah (which can range from women covering just their heads with the end of their sari or dupatta, to covering their faces) the practice is both a marker of marital kinship, as well as one that represents gendered spatial differentiation. Brides and married women are the ones who usually observe purdah in the presence of their marital male kin, or when leaving their homes— signifying their containment within protected “private” spaces even while venturing out into the public. In the instances where urban Hindu families may have abandoned an older practice of purdah, girls and women who wear salwar kameez, the long tunic and trouser, continue to drape the dupatta over their chest as a mark of their modesty. This is true of the sari too, worn by women all over India, which is wrapped around the entire body and barring the head, face or feet covers every other part of the woman’s body.

These examples aside, Indian history is replete with biographical and regional details regarding spatial and sartorial separation of women from men. The seclusion of Nambudiri Brahmin women until well into the post independence period was the outcome of both strict rules regarding caste and sexual purity, and formulated specifically in order to regulate their chastity. The terms used to refer to Nambudiri Brahmin women were antarjanam or akatamma, both of which meant people meant to stay “inside” or in the inner sphere. In fact, these women were never permitted outside on their own, and should they have done so, they were meant to cover their faces with an umbrella [marakuda] and were at all times to be accompanied by a woman servant or companion. In other words, large numbers of Hindu communities have also continually identified sartorial modesty for women as essential for the sustenance of their “culture.” The court’s assessment that the hijab violated the principle of “decorum” and “discipline” in schools then, is surprising given that Indians across communities define culture and decorum in similar ways.

Striking in the ongoing controversy are the voices of young Muslim women, with or without the hijab, who have been protesting on streets, giving interviews and writing in the press. For the most part I have found, in interviews with the affected students, or statements they have made, that they are clear headed, articulate, and angry about not being allowed to attend class on grounds of a trumped-up excuse. They understand both the politics behind this move as much as they wish to return to their classes. What is striking is that they aren’t obsessed, as are their Hindutva detractors on the streets or online, about the hijab. It is a part of them, and gives them a sense of self. And that is all there is to it. Listening to the passionate young Muslim women students who have been protesting for their right to wear the hijab has been both moving and enlightening, and I was reminded of Afsaneh Najmabadi’s brilliant essay on veiling, where she reads early 20th century male reformist writing in Iran against late 19th century women’s critique of patriarchy.5 In brief, she reads Iran’s cultural shifts to argue that while male reformers unveiled women with the objective of rendering them “modern,” such “modernized” women could never match the razor sharp, raunchy, rebellious and biting, feminist tongue of their burqa clad forbears.

In other words, the modern Iranian women though unveiled and schooled in new ways were condemned to carry the civilizational burden of a “veiled,” as in polite and ultimately docile, tongue. Cutting to the 21st century, it is evident that while there may be some convergence between Islamist ideas of pious subjectivity and those espoused by a generation of younger believers, it is also evident that their sense of self assurance comes not only from Islamist, or are even da’wah inspired, notions of devotion but also from strong strands of criticality (like ijtihad) that are intrinsic to Islamic philosophy. That aside, the ongoing oppositional movements in India, with their repeated references to the Constitution have provided these young women with a language to articulate their rights. Far from being a silent and oppressed lot, they are bright, eloquent and perfectly aware of what they want. Their self confidence and clarity are ample proof of the fact that the hijab has been no hindrance to their education until now.

The history of the veil has shown that both unveiling and veiling are complex signifiers that have changing meanings. In India, we have instances of both unveiling and veiling that have been initiated by Indian Muslim women. The early 20th century saw many Muslim women joining the national movement, giving up veiling, feeling this was the only way for them to change their own, and the country’s, future. More recently, and in an atmosphere of heightened Islamophobia in India and the world (especially post the demolition of the Babri masjid, followed by 9/11, and the Gujarat carnage), Muslim women in India, like their counterparts across the world, have donned the hijab, naqab and in many instances the burqa. The reasons are varied but at the heart of this is a coming together of a desire for community identity, cultural and political visibility and assertion, and a need to be safe within their own community in bigoted and Islamophobic contexts. In other words, in many instances, the young women wearing the hijab have chosen to do so on their own volition. Having said that, Muslim women’s assertion doesn’t come only through donning the hijab. As with women of every caste and community there is obviously immense internal difference, be it of political affiliation, forms of articulation, or about ideas of self assertion. Under normal circumstances there would have been no need to state this rather obvious fact. However, in today’s India, this needs to be emphasized. The reason for doing so is that while the coming together of Islamophobic and liberal feminist discourses in the West produced the idea (and image) of the oppressed and servile Muslim woman who needs saving (a point Leila Abu- Lughod’s superb book Do Muslim Women Need Saving makes very effectively), in Hindutva-ized India, the impulses differ.

While the ‘saving Muslim women’ [from Muslim patriarchy] impulse can be seen in action in instances like the present government leaping to outlaw the almost dysfunctional practice of “triple talaq,” in India this savior complex is twinned with a far more powerful urge to marginalize Muslims, and subdue them into submission through the use of different forms of violence. In other words, the demand to unveil hijab-clad students in the language of conforming to specific institutional dress codes is designed mainly to humiliate them into submitting to the will of the majority. The “uniform” rather than the hijab is what we must focus our attention on—both as a repressive dress code, and the far more dangerous potential that “uniformity” has for eroding personal laws, and cultural and religious differences within the country.

This is the manner in which the idea of “uniformity” is invoked in the ongoing discussions by the present government on the Uniform Civil Code [henceforth UCC]. As is known to many, the UCC came out of the women’s movements’ desire, via Ambedkar, to create a non-denominational set of laws that could have the potential for creating greater gender justice, especially in matters considered “personal,” i.e. pertaining to marriage, family and inheritance practices. In India at present these matters are governed by religion specific “personal laws.” However, by the late 1980s, seeing the potential for its grave misuse in the wake of growing communal violence, women’s groups and organizations abandoned the campaign for a UCC that they had pressed

for earlier. Instead, they drafted a variety of options that could be pursued, including the creation of an egalitarian civil code that could be opted for by anyone who wished to do so, irrespective of their birth religion.

Predictably, under the pretext of ‘saving Muslim women’ the BJP appropriated the demand for a UCC, and this remains the party’s purported reason for their now popularized ‘one nation, one code’ demand. While their desire to “save” Muslim women from polygamy is the argument that is heard most often, it is evident that uniformity, as in homogenizing a country with immense cultural and religious diversity, is what underwrites the Hindutva agenda. The BJP’s campaign, based on extreme generalizations, absence of historical detail and context, and immense contradictions between the proclaimed aim and the history of practice is advantageous to them because now the UCC can be presented as a law for the common good that is being opposed by woolly-headed liberals and secularists. A few details about the history of the UCC, its jettisoning, and subsequent retrieval are worth mentioning here.

To begin with, the attempts by BR Ambedkar, Law Minister and one of the chief architects of the Indian Constitution, to render operational both a uniform civil code, and reforms within Hindu law were both jeopardized because of the opposition from both members of the Hindu

Mahasabha and Congress in the 1940s and ‘50s. The reason was that the patriarchs of the Hindu Right did not wish for any reform of family laws or equal inheritance by daughters and sons to the family property. Though different aspects of Hindu law have now been reformed, the goal of perfect gender equality is still incomplete. Similarly, while the charge against Islam is that it permits polygamy— something that is not statistically supported—the fact that the practice exists amongst Hindus, Buddhists and tribal communities is never addressed. More recently, legal scholar and expert, Professor Faizan Mustafa, demonstrated how the much-admired Goan law permitted Hindu men to marry a second time if their first wives did not give birth to a son by the time they were 30 years of age. In fact, legal scholars like him, Flavia Agnes, and others have argued conclusively that while gender justice, and an equality of rights, is essential, this will not be achieved by legalizing a uniform code. As they suggest, the way forward would be for reform within specific religious personal laws, rather than imposing a UCC that will neither resolve the issues that are at stake, nor translate into everyday practice, as is clear from the many social laws, like dowry prohibition or child marriage abolition, that haven’t managed to radically transform existing social practices.

Unless a draft bill is made available for public discussion, it is unclear what is envisaged at present by the BJP when it speaks of the UCC; in its absence it merely adds to the fear amongst minorities, lawyers and women’s groups arguing for gender justice that this is simply a ploy to deprive religious minorities of their right to religious freedom. While the BJP ministers and supporters frequently mention Article 44 of the Indian Constitution, it is worth remembering that this is a part of the Directive Principles of the Constitution; in other words, these are guidelines for future action that, as in the case of the UCC, would require consent of communities before it can be promulgated as a law. In this regard, an argument made frequently by social justice activists and feminists that uniformity is not equality, and equality does not mean justice, needs to be reiterated. In a country with a long history of inequality and injustice, not to mention a deeply skewed and asymmetric access to constitutional and other legal provisions, the use of the term “uniform” can mean nothing other than an attempt to homogenize the population. Given that the focus of this reform drive has been on minority populations, especially Muslims, it may not be incorrect to assume that the direction of the homogenization drive, via the proposed UCC, will be to make Sharia law and its administrative reach redundant.

It is clear that the BJP has suddenly woken up to the repressive potential of the school uniform, and has decided to transform this opportunity to their advantage. In other words, it is not possible to interpret the saffron party’s support for the school uniform, and the attack on the hijab, as isolated or delinked from the larger workings of the Sangh’s political agenda. On the contrary, this is in keeping with many recent attempts at erasing the history of Islam from the country—from deleting sections and chapters from school text books to changing names of streets, railway stations and towns with Muslim associations—in many parts of the country. The hijab ban is part of this kind of “cleansing”—in this instance of removing any visual reference to the presence of Islam in the country. That aside, such a move also pushes Muslim students and teachers into a corner, where the options before them become to either comply with the ban by submitting to sartorial homogenization, or to opt out of the mainstream education system. This is particularly dangerous at a time when attacks on the madrasa system are on the increase. We have a Constitution that guarantees Indian citizens a wide variety of rights, including the rights to religion and education. Disallowing hijab-clad students from attending classes, or sitting examinations, is a direct contravention of these rights. Not resisting now will be the triumph of majoritarian bigotry, and its attempts at creating pliant, and infinitely replicable, subjects in a “uniform” nation.

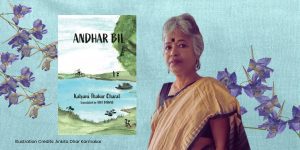

(Extracted from the book, The Hijab: Islam, Women and the Politics of Clothing by

G Arunima and PK Yasser Arafath. The author is the director of the Kerala Council for Historical Research)

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.