‘Gender, Region, Orientalist Bias Marginalised Hyderabad’s Women Urdu Writers’

Hyderabad has had a 150-year-long history of women writing prose in Urdu, a longer one of poetry and other oral and creative expressions. But we know very little of these writers and the flourishing literary scene where they carved a prominent space despite varied challenges (read more about this here and here). Urdu writing emerged more prolifically in the second half of the 19th century with social reform, greater push for girls’ education and later on, the growth of the Progressive Writers Movement in 1936. Women writers such as Tayyaba Bilgrami, Sughra Humayun Mirza, Wajida Tabassum, Jahanbano Naqvi, Zeenath Sajida, Rafia Sultana, Azeezunnisa Habibi, Brij Rani, Jamalunnisa Baji, Oudh Rani Bawa among others were writers, poets, journalists, travellers and founders of literary magazines.

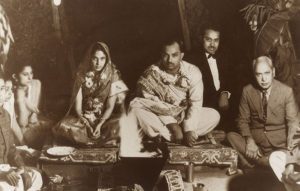

Bibi’s Room: Hyderabadi Women and Twentieth-Century Urdu Prose documents a literary tradition that has not got the recognition it richly deserves. The book profiles three prolific writers from Hyderabad. Zeenat Sajida (1924-2009) whose fascinating essays in the tanz-o-mizah (humour and satire) genre and khaake (pen-portraits) depicted gendered perspectives on the society and a glimpse into the everyday lives of women in Hyderabad; Najma Nikhat who wrote about feudalism, class struggle and patriarchy; and Jeelani Bano who, during the Jadeediyat (modernism) phase in Urdu literature in 1960s, wrote on contemporary themes of state and society. In an interview with Behanbox, its author Nazia Akhtar, Assistant Professor (Human Sciences Research Group) at the International Institute of Information Technology (IIIT), tells us why we need to not only recognise but also delve deeper into the Urdu writings of Hyderabad’s women writers.

Given how rich this literature is, why do most of us know so little about Hyderabad’s women writers and their work in Urdu?

There is triple marginalisation at work here which I also talk about in the book. The first is gender. The second is region: Urdu isn’t associated with the Deccan, which is ironic, because it was patronised and nourished here between the 15th and 17th centuries before it moved to the north, as a full-fledged literary language in its own right to be taken seriously by northern poets and audiences. There is a north Indian bias in Urdu literature as well as its translation.

There is a third problem. There is very little research on the princely states in India. This stems from the Orientalist scholarship, a major issue in the scholarship on South Asia in general, which wanted to project an image of British India as a progressive place. It was in the interests of the British to promote the idea that women fared better in British India, as opposed to the princely states, and where society and culture thrived. The princely states were presented as this Orientalist fantasy, a timeless and changeless world, a perception that was accepted at face value.

But scholars who are working on different princely states have pointed out that they were not immune to social and political events taking place elsewhere. It is only now after Siobhan Lambert Hurley’s writing on Bhopal or Razak Khan on Rampur, Kavita S Datla on Hyderabad, Janaki Nair on Mysore or Tarana Hussain Khan on Rampur that we have begun to think differently about society and culture in the princely states.

On translation, we know about North Indian writers but there again, we only know of north Indian women writers in Urdu, such as Ismat Chughtai, Rasheed Jahan, and Qurratulain Hyder, who have been translated into English. Now Khadija Mastur has joined these three or four names because she has been translated by Daisy Rockwell. People will also know about the most radical poets from north India and Pakistan like Fahmida Riaz and Kishwar Naheed. But apart from them, we don’t really know anyone else. I think there are different invisibilities and marginalisations.

We shouldn’t underestimate the role of English language translations in all this given the hegemony of the language. This is also something that is bitter-sweet, for it is the hegemony of English that is pushing our literary traditions and languages into the margins. And yet, for the women writers I document, I want to harness that power of English, in order to give them the same kind of visibility and new readership, who will appreciate their contributions and perspectives.

Why did you pick these particular writers for the book?

I chose these three writers because, first, I liked them. I could have written about Rafia Manzurul Ameen, who’s also a great novelist and she’s written for television and has a profile similar to that of Jeelani Bano. Between them, they have enough similarities to merit being put together. And at the same time, there is enough diversity and divergence between them to showcase a range of writings, concerns, themes, manipulation of genres. For instance, motherhood runs as a strong, continuous thread through all three women’s writings. But unlike Nikhat or Bano, Zeenath Sajida does not respond as enthusiastically to motherhood as the others. At heart she is a committed but somewhat troubled mother, mulling over the unfairness of motherwork and the status of mothers in the world in a manner that is more radical than that of the others. These similarities and differences offer a good first glimpse into a range of Hyderabadi women’s writings around the mid-20th century.

How did you develop an interest to research into the history of women’s writing and creative expressions of Hyderabad?

I had over a number of years accumulated texts written by these women writers. I’m not from Hyderabad, but I’ve been coming here since I was a child. Over the years Hyderabadis – knowing my interest in the literature and the history of this region – have been giving me books. Someone would call up and say, ‘Oh, I’ve heard that this scholar is releasing a book on Hyderabadi women’s writings.’ Or, ‘Have you met that writer who used to write pen-portraits and essays in the 1950s and 1960s?’ So I just began to collect books, stories and context. And over a period of time, I realised that there is a whole tradition of prose here that we don’t know anything about, which goes back 150 years, except for those whose works have been translated into English.This includes two novels by Jeelani Bano, Baarish-e-Sang and Aiwan-e-Ghazal. The translation of the first is not very readable but her first novel, Aiwan-e-Ghazal, was translated brilliantly by Urdu writer Zakia Mashhadi and yet, we don’t know about it because it wasn’t promoted very well by the publisher. The same goes for Mashhadi’s translations of Jeelani Bano’s short stories, which languish unsung. Wajida Tabassum, an intrepid writer who wrote on caste patriarchy, sexual violence in feudal homes had only two short stories translated until Reema Abbasi’s book of translations which came out in 2022.

How little is translated into English, and how little most of us today – irrespective of language or location – know about these women! There were women who were journalists and travellers, who journeyed through Asia and Europe, who worked energetically on social reform and questions of national and political unity, who developed the discourse of education for girls and women, and so on and so forth. I was just blown away by the fact that we knew so little about it all.

What were some of the surprising and interesting insights from your research into the rich landscape of women’s writing in Hyderabad?

I was struck by the sheer depth of some of the texts, which I wasn’t expecting. For instance, in 1946 essay Agar Allah Miyan Aurat Hote (If Allah Miyan were a woman) Zeenath Sajida asks fundamental questions about God, Prophet and the believer in a way that, I think, represents generations and centuries of voices of Muslim women. She expands on this theme in her other work as well. In another essay Hum Hain Toh Abhi Raah Mein Hai Sang-e-Giraan Aur, she takes Virginia Woolf’s idea from A Room of One’s Own and extends it. Why is it that you cannot have a woman Prophet? Why cannot women have full writing careers along with everything else that they have to do? These are such fundamental questions.

The other interesting insight is the range of themes that these writers dealt with despite having little formal education. Jeelani Bano and Najma Nikhat were schooled entirely at home, only Zeenat Sajida had formal education. Bano’s education was very eclectic and she was criticised by a few male progressive writers who, when she began writing about the labourers and tillers of Telangana, said ‘What does this girl who has lived in semi-pardah know about the realities of the working class?’ But women in the domestic space interact with the working class, with people from different classes, they work with them. Her novel Barish-e-Sang, I think, is the finest novel written on the lives of Telangana’s tillers and agricultural labourers, which displays her depth of understanding of class and patriarchy in a way that very few texts I’ve read in any language have.It’s not as if someone who has not studied Marx or, indeed in a classroom, doesn’t know how class works.

A lot of this material comes from the lived experiences of the women. They explore all sorts of worlds in their work, including their own personal lives, the institution of marriage, what is called mother work, the running of the household, their professional and social lives, their relationships etc.

You talk about the family magazines run by these writers as teens and young adults. Tell us more about what prompted them to start their own magazines?

They were very enthusiastic about books and learning and frequently had parents who were supportive of their efforts. But they could either not afford to or were not allowed to go to the new women’s associations and their meetings. So these young girls and sometimes even their brothers and male cousins would get together and say, ‘Okay, so we can’t get a subscription to this magazine, or this newspaper, because they’re too expensive, or they’re simply not there. So, let’s make our own magazines.’ And so they produced these painstakingly handwritten monthly magazines, which would be circulated within their families.

Jeelani Bano came from an intellectually rich but financially poor family that had a lot of talented and creative children. The family couldn’t afford a lot of paper, and whatever paper was available was used for the boys’ school work. So she and her siblings used discarded office files and old papers that had one side filled and the other side plain for their magazine.

You write about institutions that encouraged humour writing among women. That seems to be a very unique situation. Tell us more about how they fostered this unique genre of writing.

Yes, these institutions include publications such as Shagoofa, Siasat, Munsif, Rehnuma-e-Dakkan, and Andhra Pradesh. There were also initiatives by organisations such as Zinda Dilaan-e-Hyderabad, which was formed in 1973 with the specific intention of promoting humour and satire, and the Mehfil-e-Khawateen, which is a monthly literary gathering of, by, and for women. The Mehfil-e-Khawateen was founded in 1971 and has been a fertile ground for women to get together and discuss their work and for new women writers to emerge. The women’s department of the Idara-e-Adabiyat-e-Urdu also played an important role in promoting women’s humour.

Progressive writing also provided a platform [for humour writing] because laughter is a great way to expose the hypocrisy of society and also to speak truth to power. But the Progressive Writers’ Association also became hegemonic and exerted restrictions on member and non-member writers on what and how to write. Manto was almost shunned by them after he wrote stories probing the issue of masculinity and violence. Similarly, Hyderabadis were very uncomfortable with Wajida Tabassum because she talks about female sexuality and caste, which is not something that the card-carrying faction of the progressive writers was very familiar with. At the same time, writers such as Zeenath Sajida, for instance, and many other women found a great platform in progressive writing.

What you see in women’s writing is also a very clever use of the humour genre. So, Zeenath Sajida in her irrepressibly cheeky way, uses the genre of the inshaiya, or “light sketch,” to say all kinds of things which have serious implications and which are radical and subversive and completely destructive of old norms. She also uses the pen portrait (khaake), a very popular form in Hyderabad. Another proponent of this particular genre is Fatima Alam Ali, who writes intimate and vulnerable portraits of all of the great male progressive writers, and we see them in a way that we’ve never seen in any of their biographies, where they are eulogised by their followers.

The final network that’s important to remember is that of students and teachers because so many of the women writers of Hyderabad have been teachers and professors. And they have trained and nurtured each other. Zeenath Sajida, for instance, had for a teacher Jahanbano Naqvi, who was a writer herself and encouraged Sajida and her other students to write. There was a bonding and a sisterhood between them which outlived courses and degrees.

There’s an anthology of humour writing by Habib Zia where so many of the women humorists represented in it are her friends, students, teachers or colleagues.

You maintain that in the context of contemporary feminist discourse the writings of these women may seem outdated, but they still deserve to be recognised and researched.

This writing merits investigation from the perspective of a history we have to restore. Of course, it’s going to be different from the kind of writing that you have today because it belongs to another period. I frequently come across this problem with my students: when they read [19th century feminist activist] Tarabai Shinde’s essay ‘Stree Purush Tulana’, for example, they say, why is she saying that though marriage is unfair to women, it is still important for women to remain married? Why isn’t she speaking out against marriage? But it was too early in the day for that kind of radical intent to happen. Tarabai may have thought about it, but it was not the time to articulate the total rejection of marriage. Similarly, you cannot expect someone like Najma Nikhat to make an argument such as ‘Why is raising a daughter a bigger deal than raising a son? Why isn’t a father held responsible for raising a child, daughter or son?’ Najma Nikhat lived in a different world. We frequently forget that we have been able to reach this stage where our politics is so much more radical — and we can articulate positions that are so much more empowering — on the shoulders of these women. We can actually talk about how marriage and motherhood no longer define a woman.

Let’s take Jeelani Bano as another case in point. Bano is very critical of women working outside the home; they are always portrayed as somehow morally compromised in her writing. But you also have to remember that this is a home-schooled woman, who faced the snobbery of the intellectuals and those who were formally educated. It’s easy to understand why she would think of people in workspaces as somehow hostile to her and her world.

Najma Nikhat’s The Last Haveli is an incredibly evocative story of the place of working women in feudal establishments or deodis.

What drew me to The Last Haveli is that it’s a brilliant, jewel of a story. From it you get a great sense of Najma Nikhat’s considerable power as a writer and what she could have done if she had an easier life. It is difficult in a short story to have well developed characters, and yet she manages to do that with great beauty and depth. But what drew me to it is that it conveys what life was like in the feudal deodis for women of all classes, whether they were upper-class begums and ranis or their handmaidens and slaves. And while she depicts the problems that women of all classes face, Najma Nikhat’s sympathy is always with the working-class women. It’s through their eyes that we look at life in the deodi — the realities they face, the work they have to do, the sexual services that they have to provide, the beatings they take as slaves with no place else to go, while also not being allowed the right to express the fact that they exist or have feelings and thoughts. There’s another story in which Nikhat points out that the best attribute in a woman or a wife is “tonguelessness,” which is a searing reminder of how patriarchy demands that women must be seen to be working silently and are never heard.

Could you tell us something about Begumati Zubaan, the Urdu dialect spoken in the zanana, that is used profusely in Nikhat’s story?

This language that women spoke amongst themselves in the zananas was unique to them and reflected their circumstances, such as their lack of formal education. It was not the “polished” diction of the men in the family, who would have far more interactions with the outdoors and would have had more education than the women in their families. Begumati language developed in the zanana amongst women of different classes, because even the upper-class women probably had more interactions than the men in their families did with working class people, such as their domestic help as well as vendors, hawkers and traders, who went door to door selling their wares and exchanging news and views. So it developed during interactions between people of different classes, reflecting the influence of different languages and dialects and a unique, gendered worldview. A lot of the expressions of Begumati zubaan will seem sharp and very dramatic to us. This includes those that talk about women’s bodies, for example. There’s an expression that the narrator uses in The Last Haveli, which I’ve translated as “cast[ing] stones at her barren womb”. This is a direct translation from Begumati Zubaan: apni baanjh kokh par patthar marna. Begumati zubaan was replete with rich expressions that were not considered “polite” in their time, such as those that contained sexual innuendo or different kinds of euphemisms. And the fact that men were not a party to this language also contributed significantly to its development.

Gail Minault has done some work on this aspect of women’s language. There are Urdu books written in the early 1920s, and 30s, all by men, who were linguists interested in documenting this language. But even before that there were social reformers who documented it because they disapproved of it and wanted to do away with it. They said that this language of women was a sign of women’s ignorance and backwardness. Ironically, it is through these reformers who wanted Begumati Zubaan to vanish that we know a little bit about it.

Your book is largely about women who wrote in Urdu while Dakhni is believed to be the prevailing language in Hyderabad. So, do we see any influence of Dakhni in their work?

There are at least three languages here at play: one is Dakhini, the other is Hyderabadi, which is slightly different, and then there is Urdu. The historical context for these languages and the politics between them has to do with the Mughal subjugation of the Deccan in the 1680s. Over the course of the 18th century, Mughal governors and the Muslim and Hindu ethnic groups and communities that migrate with them bring standard Urdu, and this replaces the language of the defeated, Dakhini which begins to be seen as inferior. As a result, most prose, written in Urdu by Hyderabadis today, is standard Urdu. Dakhni was close to what is known as aam zubaan, the common tongue, and it was what the Dakhni poets, kings, courtiers, and Sufis used to connect with the people. The medieval Deccan was also a very cosmopolitan and diverse world, so Dakhni absorbs all kinds of words and structures — it derives a lot from Marathi, for example, because the Sufi saints had very close associations with the Bhakti saints of Maharashtra. It takes a lot from Telugu because there was a very strong Telugu presence at the courts of the Deccan.

But this idea that Dakhni is aam (common) zubaan and different from adabi (cultural) zubaan takes root slowly over the 18th and 19th centuries and Dakhni is ushered out. Zeenath Sajida, who was one of the most passionate proponents of Dakhni, never wrote in the language, because it had simply no status as a literary language anymore. Similarly, in the case of Jeelani Bano, who is also a passionate advocate of Dakhni, you will find that Dakhni is used by characters who are either less educated, which is frequently women, or by those who are naïve and not worldly wise. Such usage sends a message about the status of Urdu and demonstrates and embodies the historical marginalisation of Dakhni in the place of its flowering.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.