The 19th Century Woman Who Challenged the Image of Indian Coupledom

Historian Uma Chakravarti on Pandita Ramabai's radical photographs of conjugality and its discontents.

[This article was originally published on The Third Eye and can be viewed here.]

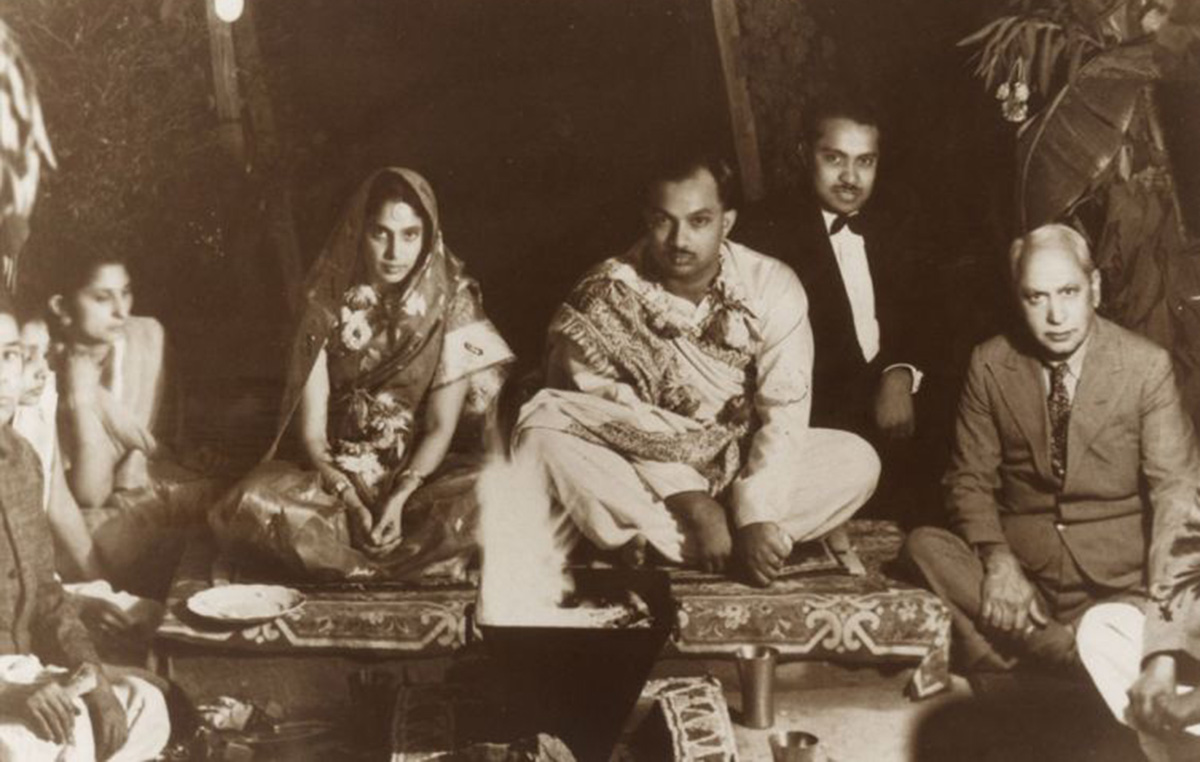

The period between 1870 and 1920 may be regarded as the high moment for pushing the conjugality/new conjugality project Nae Dampatiya Rishtey (Ek Vivahit Jode Ki Ek Nai Kalpana) across India and this is well reflected in Maharashtra too. Women’s autobiographies published during this period never fail to hold up the ideology of new conjugality in the form of the husband-wife duo, reproducing the new reformed household through their joint effort. In the extreme case, a wife might write about the husband rather than herself as we see in Ramabai Ranade’s ‘autobiography’. Novels too privilege the love that sprouts between two young people suited to each other through similar caste and class locations and ends in the creation of a husband-wife duo, perfectly matched to each other through temperament, training and culture, creating the perfect reformed Hindu household for a new moment in history.

Other husbands also went on to encourage their wives to write their autobiographies, enjoying this public celebration of having led their wives from darkness to light, especially gratified by the wife’s defence of the new patriarchy.

Once published, these autobiographies were disseminated among the reforming elite and worked to consolidate companionate marriage under the undisputed leadership of the husband. This stage of social history has been has plotted for us in the last two decades by feminist scholars with great skill. What has been less well explored is the underside of this process: the valorisation of the reformed and modernised Hindu household, the subject of women’s autobiographies, had its discontents . This was evident primarily through the figure of the widow who disrupted the neatness of the reforming Pygmalion and the child-wife wherein the husband led his pliant wife to occupy her due place as the mistress of his heart and the queen of his household. Not surprisingly the voices of the widows were submerged in the rhetoric of conjugality as were the voices of others who critiqued the shallowness of modern husbands who had no real investment in the recasting women project, content to have acquired the accoutrements of modernity without its substance. which Tarabai Shinde did so forcefully, but was attacked so viciously that she never wrote anything else ever again.

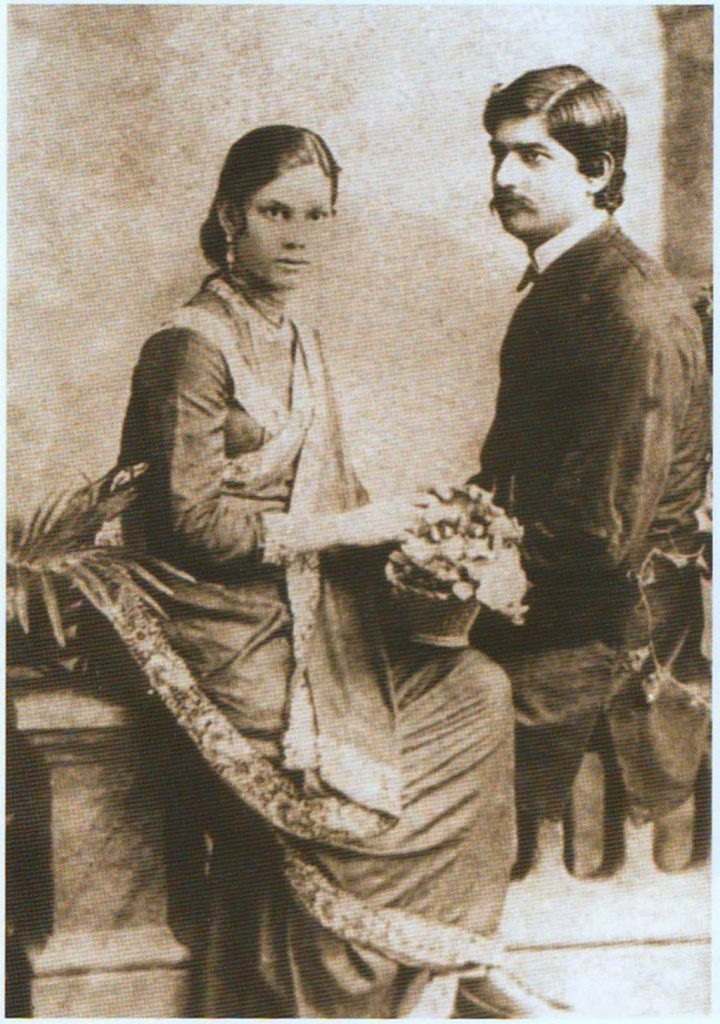

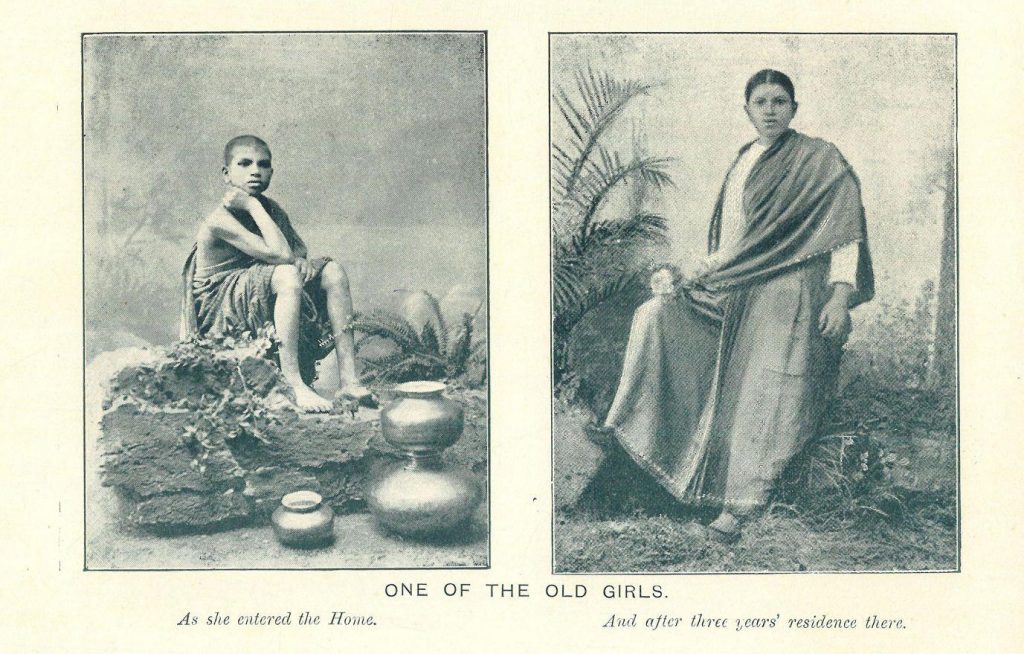

I want to shift the focus in this paper from women’s writing, even as I continue to draw upon it, to focus on Pandita Ramabai and her use of the photograph to document women’s non-conjugal existence, the redefining—even the subversion—of the family that happens through the photograph. Moving away from the husband-wife photograph which ultimately became the visible symbol of new conjugality in the 19th century (and continues to dot our drawing rooms to this day, proudly displayed by families as necessary symbols of the modern household) Ramabai rewrote even the ‘happy family’ photograph, as she used the camera to capture the battered conditions under which child wives/widows arrived at her doorstep. Sometimes she coupled them with pictures taken years later, showing the transformations in the persona of the girls who had spent a few years in the Sharada Sadan, her home for widows.

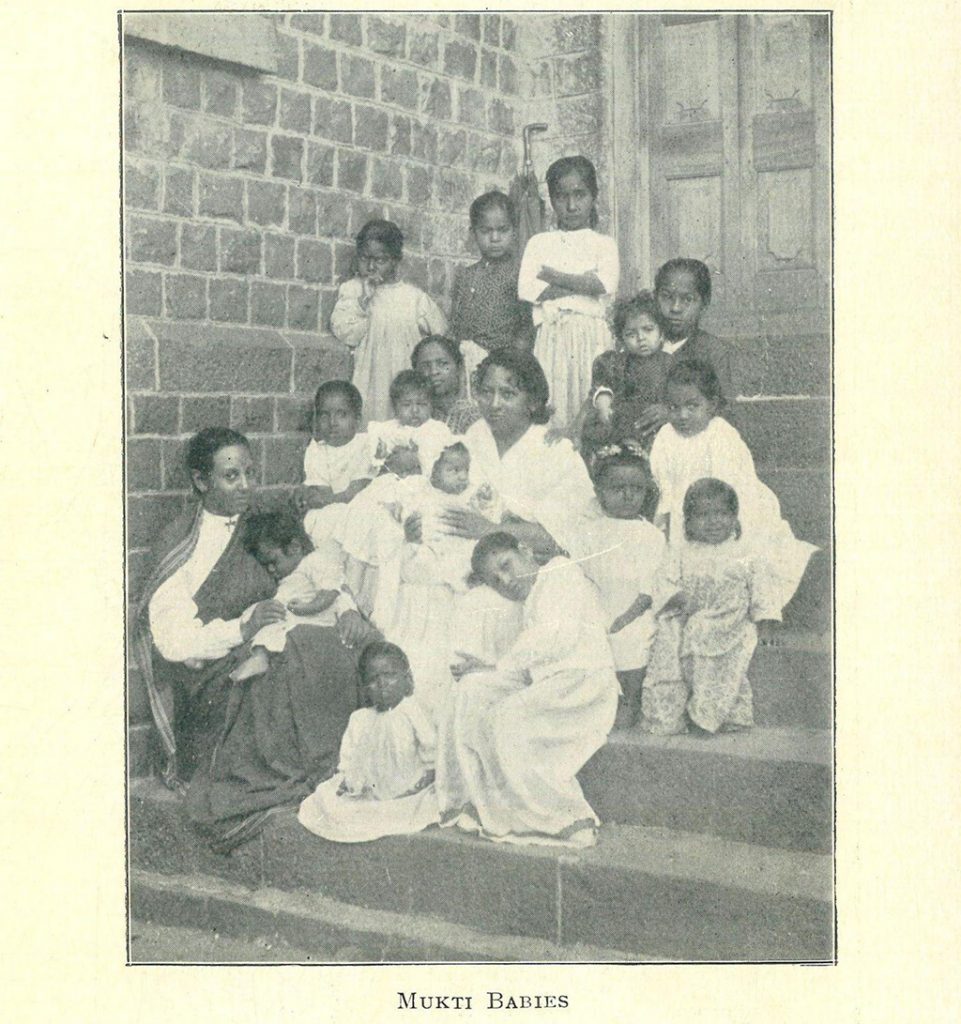

At other times, she turns the tropes of the family photograph to capture the new family that she creates: the family of waifs and strays gathered from many sites and from different distressed conditions.

In one beautiful picture, Ramabai and her daughter Manoramabai, whom we can see earlier in a few studio photographs of the widow mother/child duo, are the centre of the new family of affiliation that they have created, surrounded now by a number of little girls of assorted ages. At the centre of the photograph, Ramabai holds a baby in her arms, while another little girl movingly rests her head on her lap. Close by, Manoramabai sits with another baby on her lap, while mother and daughter are surrounded by other little girls. We know from a little account published in a book in the early 1900s of how Ramabai worked out ways of making a large group of famine-relief children feel at home within a strange space. All the older little girls and young child widows were requested to take one of the newer ones, in a sort of adoption, so that they could feel loved and cared for even in the midst of great distress and abandonment.

Among the most striking pictures are various photographs of her post-famine extended family—hundreds of widows in one picture and hundreds of little children in another. These amazing photographs, captured by using some technique to piece together segments of the group to make a whole at a time when the wide angle lens was not available, stunningly show us how dramatically Ramabai pressed against the boundaries of conventional thinking in her own life and work, never failing to document that process with all its dramatic intensity.

Other photographs suggest that in Ramabai’s world new family affiliations are not always about large groups but also of small, intimate relationships: we have many portraits such as that of a mother and her two daughters.

The caption tells us that the mother was a Hindu, while the elder daughter had converted to Christianity; nothing is stated of the younger daughter: either way the information seems to be irrelevant in reading the picture. All three women nestle comfortably against each other with the mother at the centre seated on a chair; the older daughter, who may have been a child widow at Sharada Sadan and been among the girls who converted to Christianity in the move that led to a furore in Poona, stands behind her with an affectionate hand over her mother’s shoulder while the younger daughter sits on the floor, also with an elbow resting on the mother’s lap.

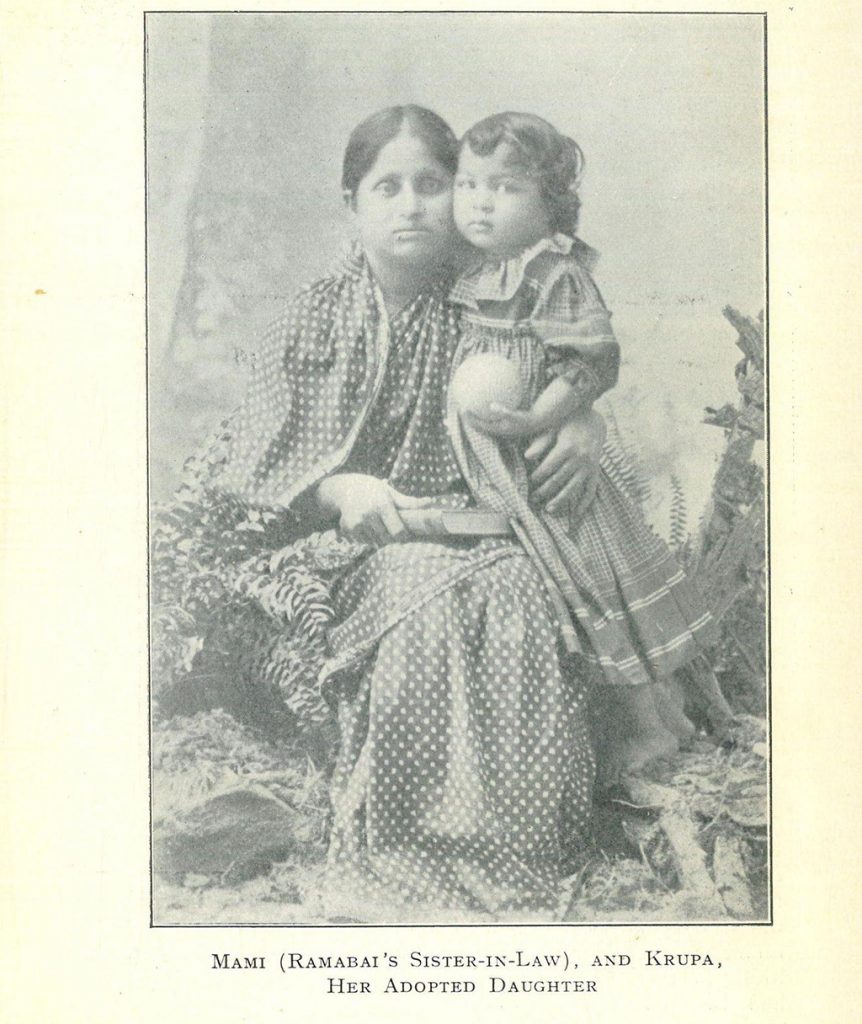

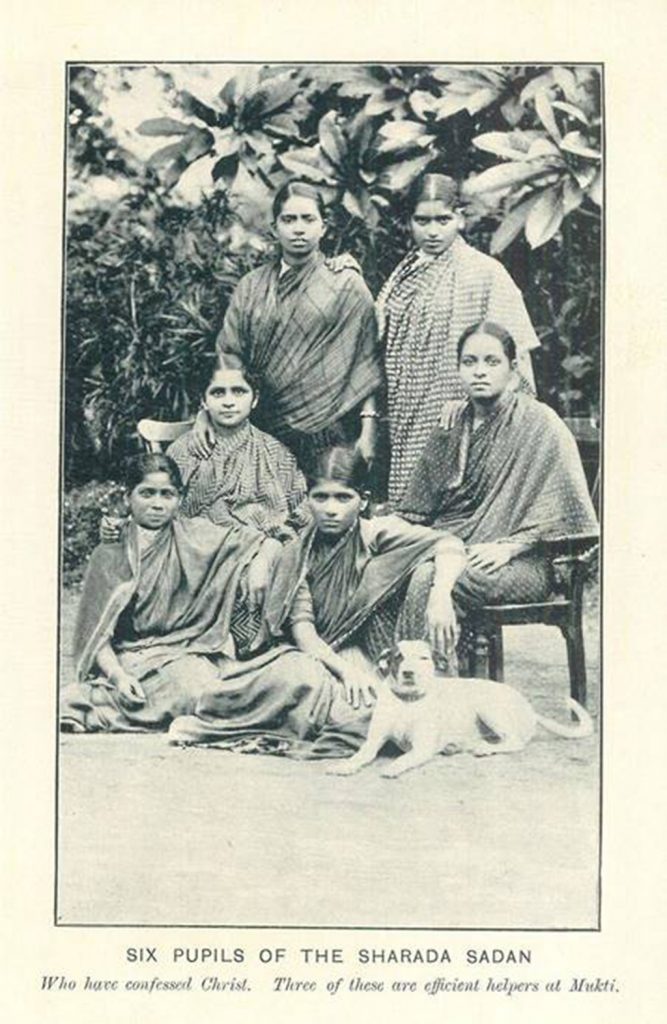

Another one shows Mami, Ramabai’s widowed step sister-in-law who was childless and unwanted in her marital home at her new home in the Sharada Sadan with Ramabai. Mami adopted little Krupa, meaning grace, who was found abandoned on the road as a little baby. Krupa nestles by Mami’s side holding a ball, her cheek against the mother’s face, the mother’s arm around her, holding Krupa close. Mami had been the second wife of Ramabai’s step-brother, much resented for that and so Ramabai had brought her back to Poona, giving her an honoured place and a new life in the institution she set up for the ‘social pariahs and domestic drudges’ of her time. Many of these intimate portraits were clearly taken in a studio but others are taken outdoors. In one, such six young widows who are studying at the Sharada Sadan sit together in another picture taken in the Sadan grounds as a dog too sits comfortably in the picture, perfectly at home in its everyday surroundings.

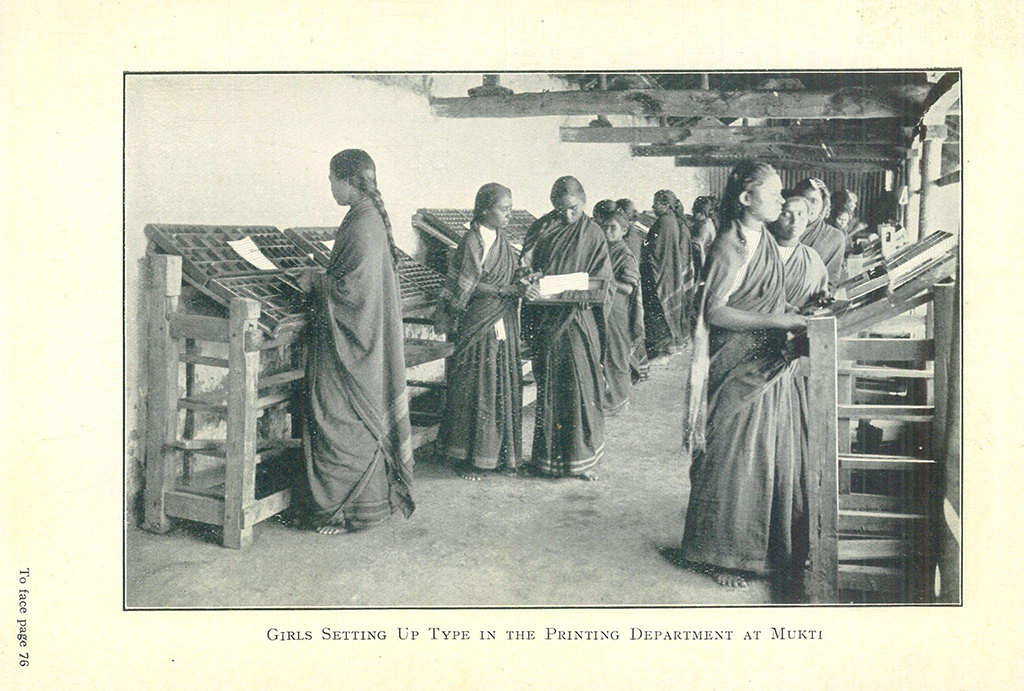

The Sharada Sadan, literally a home dedicated to learning, was unable to continue in Poona, after Ramabai brought hundreds of children, mainly girls, back from the famine-stricken areas of the central provinces in 1897, because the middle-class community in the city were horrified at the very sight of the rural children she had given a home to. Ever resilient, when the cantonment board gave her an ultimatum to forthwith remove the children because they were dirtying up the city, she simply relocated all the famine children to Kedgaon, some 50 miles from Poona where she had bought a 100-acre piece of land hoping to generate an income by planting fruit trees there. But this meant raising resources to feed the new extended family. And that was not going to be so easy since the Ramabai America Association had withdrawn funding after the conversion controversy and the resignation of the old board. These constraints may have been the context for what Ramabai finally did with Mukti Sadan, the new institution she built in Kedgaon: she turned it into a place of study and a site of work, placing Mukti Sadan on the road to self-sustenance. I read this move on her part as a new way to think about reproducing the family in a situation where there were few conventional resources at her disposal. As the younger branch of the Dongre family, one that was peripatetic and had no resources such as land or wealth, and in any case none that she would have been entitled to as a woman, and having made an inter-caste marriage solemnised under the civil marriage act which disinherited men under Hindu law, she inherited nothing from her husband on his death, paying off his debts instead. In a mistress-stroke of entrepreneurship, Ramabai seems to have turned the land at Kedgaon into a resource that would produce food and other goods for the inmates of Mukti Sadan.

This attempt at the social reproduction of what was intrinsically a shifting community of girls and women, who went in and out of Mukti Sadan, led to growing vegetables, running a dairy, spinning and weaving, and book printing among a host of other activities providing them with working skills that they could use later in life. This too she documented through a series of photographs which are quite unique for the 19th century, as these were activities that women performed outside the conventional household, which was the seat of normal reproduction: children, and its concomitant, property, to pass on for them, without which the normative family would simply die out.

How different all this was from the ideologies dominating the 19th century is well borne out by a comparison between Anandibai Joshi and Ramabai. As is well known, Anandi defended child marriage in America, wrote her husband letters referring to the violence she was subjected to by him but proceeded to express wifely sentiments, even wondering how she should greet him on his arrival in America as her American family would expect them to kiss.

She combined these new rituals to express proper conjugal sentiments with opinions she held firmly to from her early Brahmanical socialisation: caste and class boundaries that must be maintained at all times. Not surprisingly, her thesis titled ‘Obstetrics Among the Aryan Hindoos’ was on childbirth, as she hoped to practise gynaecology on her return to India and wrote her medical thesis on childbirth. Among her observations on feeding the infant if the mother is unable to do so herself, are instructions on using the services of a wet nurse. She wrote:

“The wet nurse should be of the same caste and class as the child. She should have a perfect body, good complexion and a loving nature. She should be of medium height, middle age, and in good health, devoid of chronic diseases and non-covetous [in nature]…Her milk should be of good quality and flow easily. She should present a good family history…She should not nurse more than one child…Feeding on her milk the child will naturally inherit good or bad quality…to say nothing of the influence she exerts over the baby both moral and intellectual…”

I am not surprised that there is an attempt to create a couple-type photo of Anandibai and her husband Gopalrao in a new book approximating to an archive on Anandibai. Her death soon after her return to India, educated but still unconverted, led to a paroxysm of emotion, almost a hysterical funeral, since she had died as a ‘sumangali’, and was photographed before the final rites. She had to be remembered as the archetypal Hindu wife. There are also a number of earlier photographs taken when Anandibai was studying to be a doctor at Philadelphia: a lovely photograph of her with two other oriental women, also studying to be doctors, and many of Anandibai wearing the sari in the Gujarati style but called the Hindustani style in contrast to the nine-yard Maharashtrian version which was cumbersome to wear in a cold climate. One of these photographs sent to Gopalrao was the subject of criticism by the husband located many thousands of miles away but still able to assert his husbandly powers of surveillance over her. Anandibai had to defend herself by evoking the argument that no harm had been done in her wearing the sari in the Hindustani style as that too was a dress of her own people!

I am certainly not surprised that there is no couple photograph of Rakmabai and her husband Dadaji given that he took his young wife, with whom his marriage had not been consummated, to court on a restitution of conjugal rights case to gain control of the considerable wealth she had inherited by a will from her father. This case came to be infamous in India since in refusing the plaint, Rakmabai challenged the validity of the marriage itself on the ground that it had been entered into when she was a minor and was in that sense non-consensual, generating mass hysteria because Rakmabai had not lived to ideal notions of Hindu conjugality. After the threat of her going to prison for failure to comply with the restitution of conjugality law had been averted through Rakmabai literally buying her freedom from Dadaji, she went on to England to become a doctor, a stage of her life for which we do have a single but beautiful photographic record. What remains intriguing is that while there is a stunning photograph of Ramabai as a young woman before she was widowed—photographed with a set of books c.1880—and there are innumerable photographs of her after she became a widow, and we also know she did use the photograph so powerfully: strategically using the widow’s garb closely wrapping herself on one occasion in America in white from head to toe, appearing almost as if she were a nun—something she never did in India, creating an image so different from the Indian prince look photograph of Vivekananda. The irony in this is not lost on us as Vivekananda launched a tirade on the materialist west which was in desperate need of eastern spirituality [we not only have a photograph of Vivekananda in this ‘garb’ but also a description of how he used velvet and gold braid to create that image!].

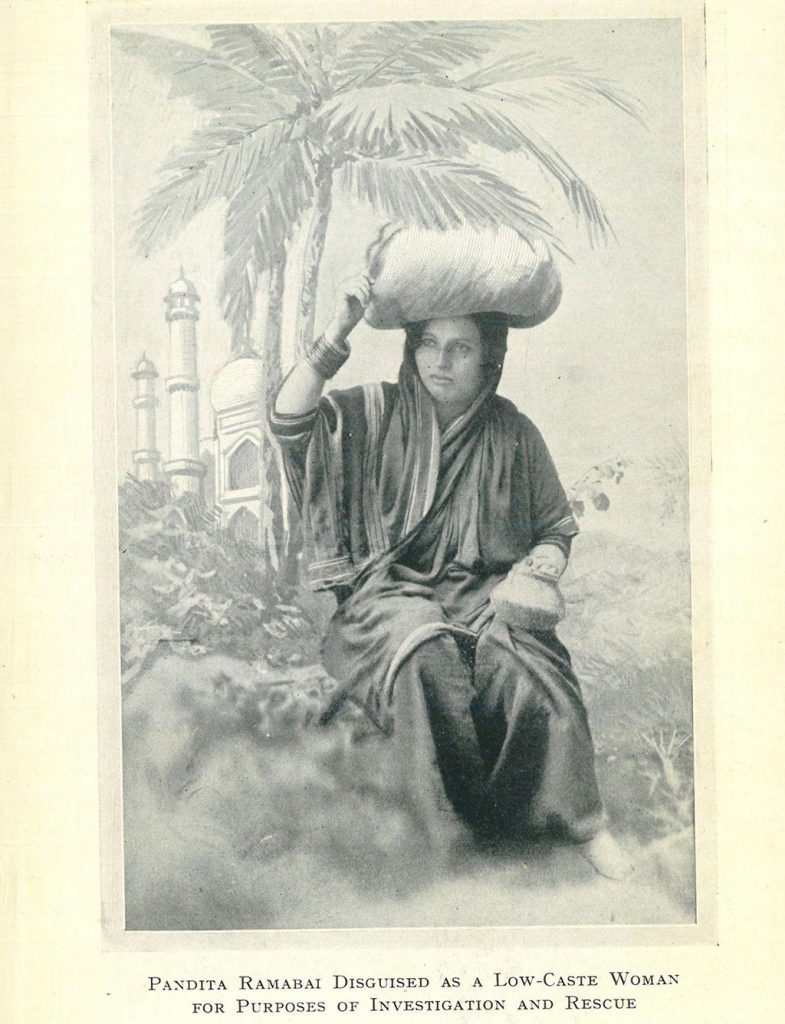

Another amazing photograph shows Ramabai in disguise as a Mahar woman so that she could travel incognito to rescue widows from Brindavan. This photograph is somewhat ironical: both Ramabai and her husband were out-casted by their communities for making a hypogamous pratiloma inter-caste marriage. So there is some humour here in the particular garb that Ramabai chooses to take on—that of a low-caste woman—for her disguise. Even more interesting is that in another picture where Ramabai is dressed as a Mahar woman, the picture is picked up and published in a book on the ‘Wrongs of Indian Womanhood’ but appearing there simply as a picture of a low-caste woman!

And yet there is no photograph of Ramabai with her husband. We are left wondering: was there one that she did not preserve in her documents, or was its absence indicative of its irrelevance in her life? We will never know. The ‘archive’ of the moment, i.e., the one that exists at the moment, is silent on the existence of such a photograph. And so we must perforce leave it at that—the archive can never answer all our questions: some must remain in the realm of our imaginations. In sum, there are other histories to be told even for the age of a near-frenzied investment in the new conjugality project of the 19th century.

Our Newsletter

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.