Why Women Stringers Are Missing From Telugu Media In Small Towns

The job is too ‘dangerous’, ‘dirty’ for women, say male-dominated newsrooms

I reached the venue of the annual meeting of the Andhra Pradesh Union of Working Journalists (APUWJ) at Kanchikacharla village in Krishna district at 8.40 am on May 27, 2012. It was a wedding hall in the open fields on the arterial Vijayawada-Hyderabad highway. The meeting was attended by hundreds of working journalists from nearby districts along with journalists from the Vijayawada/Krishna district. There was a tea break for half-an-hour at around 11 am and everyone rushed to the washroom, which was full. I walked out of the hall and strolled towards the office room of the function hall to check if there were any other washrooms on the premises. The manager was watching Satyamev Jayate, a popular TV programme on a Telugu news channel and took a while to notice my presence. Without uttering a word, he raised his eyebrows. I told him in Telugu that I was looking for a washroom as the one inside the function hall was full. He replied: “Best thing. . .go outside.”.

I walked across the highway only to notice that scores of attendees at the meeting had dashed in different directions to find a bush or a tree to relieve themselves. This en masse urinating session blocked the traffic on the highway. An AP Road Transport Corporation bus too had stopped and male passengers had got down to ease themselves, while their womenfolk stayed on board. It was when I saw the stranded women passengers that I realised that there were no women in the APUWJ meeting. They were not only absent from the dais but also the audience.

Moreover, the women had to watch scores of men all around urinating in the open. The scene was an evocative metaphor for the gendered world of Indian-language newspaper stringers. That it was utterly quotidian, a given, taken for granted, only underscores the embedded forms of patriarchy within and outside the journalistic field that the stringer inhabits and which is exclusively male. There are no women stringers. Yet women haunt this space and shape the masculinity of the men in the public sphere in many ways.

Stringers are local news contributors, not on the payroll of the organisation for which they work. Most function as part-time journalists and are paid on the basis of the length of their contributions. They are recruited in an informal manner and have little job security. The term ‘stringer’ can be traced to a time when part-time news reporters were paid by the column inch. Instead of receiving a fixed compensation for each story written, a stringer would use a piece of string to measure the amount of newspaper space occupied by his/her writing.

Stringers are present in every mandal (a block of villages) in a district. While they are in urban areas too, the focus here is primarily on mofussil areas. Apart from contributing news to the organisations for which they work, stringers are also responsible for generating revenue by procuring local advertisements, boosting circulation, along with handling any informal work assigned to them by the heads of reporting/editorial bureaus and managements.

Importantly, apart from the lack of regular salaries, stringers do not have any specific work timings, medical and life/accident insurance, holidays, weekly offs and other perks to which formal workers usually are entitled. In the newspaper organisational hierarchy, stringers are at the bottom of the ladder. While most of the editorial and reporting staffers belong to upper-caste and salaried class (middle-income group), most stringers in the Telugu-speaking states belong to the lower strata of the Hindu society in terms of caste – Other Backward Classes and Scheduled Castes, often referred to as Dalits.

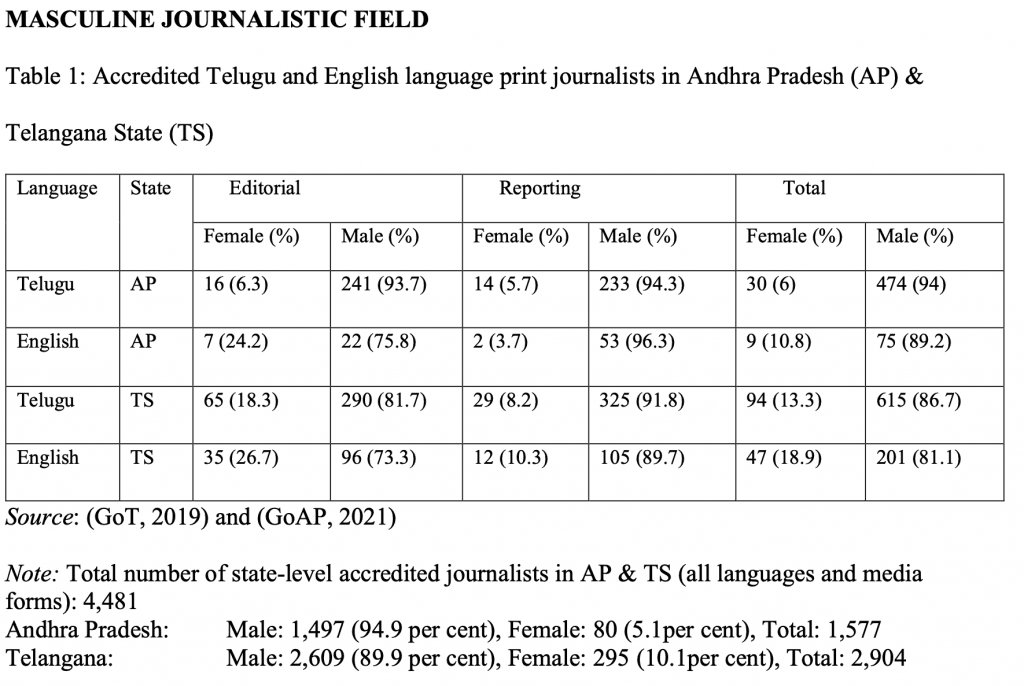

In this chapter, I examine the space that the absence of women stringers in Telugu journalism leaves and the nature of the Telugu masculinity that inhabits that space in small-town Andhra Pradesh (AP) and Telangana (TS). The ethnographic fieldwork was carried out between April 2012 and October 2014. The updated secondary data on sexual diversity in Indian and English-language media was culled out from various government sources as recently as December 2021. The small towns – Gannavaram and Sangareddy – were chosen as they have a blend of both rural and urban character along with their proximity to capitals of AP and TS, Amaravati (Vijayawada) and Hyderabad respectively.

What are the anxieties, desires and embodiments of masculinity in the stringer and the field he inhabits? How do women feature in the imagination of the stringer? What are the languages of the precarious and slippery masculinities that the disenfranchised and culturally deprived stringer speaks in relation to the upper caste women they encounter? These are some of the questions I explore by presenting ethnographic observations, documenting everyday utterances and practices in the life-world of small-town stringers in India.

Masculine field

During fieldwork, I gathered responses from the editorial and reporting heads of Telugu dailies about the absence of women at the local level, which ranged from sympathetic to sexist. Some even sounded dismissive saying that “there are more ‘serious’ issues to study about journalists” or patronising, sermonising about ideal world situations. In fact, the language is such that reference to a stringer was always a default ‘he’ or ‘him’ in Telugu language. This was the case even while referring to an abstract situation involving a non-existent stringer.

The editorial in-charge of a leading Telugu newspaper based in Krishna district said that they tried “experimenting” by recruiting a woman as a stringer and it “failed” because she could not cope with the “work pressure” and quit the profession in a very short time . The response of the editorial heads of other news dailies, including the progressive and left-leaning ones, to the same question was similar in both the Telugu-speaking states.

In a similar manner, VRK, a bureau in-charge of the Medak district edition at Sangareddy, said that in his experience (of more than 24 years), he had not seen any woman from Sangareddy willing to work as a reporter or a stringer in the mandals. “Those who were educated and passionate about journalism look for opportunities in Hyderabad instead. No intelligent/sensible woman (telivaina āḍapilla) would want to work as stringer,” he said. Echoing the tone of a majority of salaried staffers, NS, the rural in-charge of Sakshi daily in Krishna district, said: “We always recruited people on the basis of their abilities. If a woman was ready to work as a stringer, we never stopped her. But it would be very tough for women to travel alone or along with male stringers in villages to file stories or cover issues. This is the main reason for the absence [of women stringers and reporters.”

When asked why more women were recruited for desk jobs, a Telugu adage was repeated by many stringers, staffers, and editorial at multiple locations: Tirigi āḍadi tiragaka magādu cheḍatāru (A woman turns ‘bad’ by wandering and a man by not wandering). More shockingly, a handbook for journalists (Reddy, 2016, p. 286) written in Telugu, rephrased the above adage while describing the essential characteristics of reporter or stringer: Journalisṭu tiragaka cheḍatāḍu (A journalist turns useless by not venturing out). Notably, the gender of the journalist in the description was masculine.

A senior journalist explained that instead of heavy-duty reporting, many newspapers encouraged women to contribute or work in the family, women, and Sunday supplement sections of Telugu newspapers. Explaining the overtly masculine nature of the peer group and the field, PSR, a stringer with many years of experience in Sangareddy, said: “How can women maintain a working relationship with these ī baṭṭebāzgāḷḷu (uncouth fellows)? Women’s lives will be spoiled, as this is not an easy job to do.” The stringer implied that women may suffer material as well as symbolic losses when employed as local journalists. PSR also pointed out that sharing of information related to local news or dealings with government officials, businessmen, and politicians was not possible with women in the journalism field at this level.

Whether it was in Sangareddy at the labour aḍḍa (pick-up point) on the highway centre or in the industrial estate (cottage industries) located near Surampalle village in Gannavaram and in the farmlands, women outnumbered men in heavy-duty work agricultural and construction-related works. Also, women were seen doing ‘soft’ jobs such as running small shops, roadside eateries and working in balwādis (rural preschools) and anganwādis (rural childcare).

However, the situation in journalism is different from other professions or jobs: many stringers often said that journalistic work was masculine (mogōḷḷadi) and it was “too hard for women to work in on a daily basis”.

On many occasions, I accompanied stringers while they were interacting with women from different sections, officials, schoolteachers, nurses, wardens, and local entrepreneurs among others. Passing an uncalled-for or lewd remark right after their work got done was common, especially in the case of relatively younger stringers.

In one instance, PR, who referred to a lady official as ‘Madam’, started body-shaming and slandering her while talking to another stringer. He would use coarse Telugu expressions such as “dāniki balisindi” (temerity) and “kottallo intē unṭundi” (she resists because she’s new). Balisindi literally translates as ‘fattening of body parts’ (in this context) while kotta translates as ‘new’ or ‘fresh’, but the way it was intonated alluded to a woman’s virginity. Referred to as ‘double-meaning dialogues’, women dealt with such insults often in both urban and rural areas. The way stringers address women in their absence or behind their back often changed from the ‘miru’ (plural, formal and respectful ‘you’) to ‘nuvvu’ (singular, casual, and disrespectful ‘you’).

While reading the biographies of veteran Telugu journalists for my doctoral research, only one senior editor Potturi Venkateswararao (2015) mentioned recruiting women in a mainstream newspaper (Eenadu). He was one of the founding members of Eenadu editorial team, which was established in 1974. While recalling the recruitment and training process he oversaw in the newspaper, he wrote:

For the first time in the history of Telugu newspapers, we have recruited five women as sub-editors. I took great care regarding the safety of women journalists. I was almost like the head of the family. Even now when I see them (decades later), that feeling of being a proud father comes to the fore (p. 119).

Even as it sounds patronising and invokes familial claustrophobia, this was the sentiment that most progressive men seemed to hold in newsrooms. Political scientist Robin Jeffrey in his book India’s Newspaper Revolution noted a similar response about a woman journalist working in an Urdu daily based in Hyderabad, where she “seemed to perform her tasks to the satisfaction of her editor and colleagues, who treated her presence as special – like having a daughter or sister working with them” (2010, p. 173).

After sending reports to the district edition centre by 5 pm, the then Gannavaram stringer for Eenadu daily ANR, agreed to give me an interview. Among many other things, he stressed that the reason why he entered this profession and continued was for “gouravam” and “maryāda” (respect and honour). What struck me was his ‘statement’ about the status of women in the profession, which he made while sucking on a peppermint candy: Gurram chēsē pani gurram cēyāli, gāḍida cēsē pani gādida cēyāli [A horse should do the job it was meant for and a donkey should do its].

This utterance encodes a crude sexist and casteist idea of division of labour in Telugu society: men perform ‘honourable’ and ‘competitive’ functions in public (like horses) while women perform ‘menial’ and ‘domestic’ tasks (like the donkeys that assist local washermen [cākalivāru or dhobis belong to OBC community in AP and TS]).

In Sangareddy, on the eve of Bathukamma – the major festival in the state – a stringer-cum-photographer PR was visibly overenthusiastic on getting ‘colourful’ photographs of women carrying Bonam (offering). “There should be some colour in our life too, which otherwise is filled with filing reports on financial frauds and farmers’ suicides,” he said. The front page of tabloid edition and the centrespread had women wearing gaudy and colourful sarees offering Bonam to Goddess Durga. During the entire coverage of the festival, voices of women taking part in the festivities were absent but they were present only in images.

Often, the idea of women working as stringers and reporters was considered ridiculous. When asked how it would be if women worked as stringers, the response was: “It will be nice, Sir. Women will bring a daily dose of entertainment in our everyday lives.”

Even the everyday language of various agents was sexist and would make women uncomfortable if they were to work in the field. Stringers and journalists, like most locals, often make fun of their peers by using expressions, which are ableist and sexist at the same time, such as “Stop behaving like a woman”, “Speak up; don’t be a dumb c@#t”, “Don’t make a cry-face like a woman”.

Also, it appeared that men themselves would feel uncomfortable in certain situations if they had to work alongside women in the field. For instance, stringers as part of their everyday work while interacting with local politicians, businessmen, police, and small-time bureaucrats gossip about the extra-marital affairs of locals, discuss strategies to outsmart their competitors/peers in government offices, nefarious businesses, and private and public information about persons in opposing political camps. These are conversations in which pertinent oppositions such as acceptable/unacceptable, pride/shame, public/private, legal/illegal, domestic/public, permissible/impermissible, and inner/outer are suspended. This stems from deeper insecurities of men especially about their work and the need to maintain varying degrees of dominance over women in the social space.

The field also revealed the absence of infrastructural and structural support for women. The non-applicability of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, India too is a corollary of stringership because they are not on the payrolls of media organisations. Further, there is no workplace as such for stringers and sometimes even daily newspaper reporters since they are in the field most of the time, a condition which holds good for reporters based in urban areas, state capitals, and the national capital too.

Addressing this, journalist and media analyst Geeta Seshu observed:

The sexual harassment women journalists face isn’t just at the workplace, inside newsrooms, with colleagues or bosses. It happens even when journalists, especially reporters and correspondents, go out to work – in the field, during interviews or meetings with sources who hold out the promise of an exclusive tidbit. […] Even as they report on sexual harassment elsewhere, they are as vulnerable to it at the workplace. They experience a low-level sexual abuse that they often ignore, not wishing to jeopardise a good assignment or be treated differently from their male colleagues (Para 1 & 2).

Most stringers were out at various locations in the mandals and villages during the day and filed their stories sitting under trees or in shutter shops at many makeshift media points. There were no facilities such as public toilets in small towns and villages at the time of my fieldwork. Even in most government offices, schools, and hospitals, the sanitary conditions were not congenial for women. Most stringers, all men, did not hesitate to attend to nature’s call in the corners of streets or on farmlands.

During fieldwork, I observed that stringers and sometimes even reporters would be courteous and cordial towards women if they happened to be victims of some situation or in a helpless position – the non-payment of a monthly pension or the untimely or accidental death of a husband, for instance. Girl students who were achievers or women playing during Bathukamma (mostly upper-caste) also commanded the respect of stringers. If the vulnerability of women as victims made for a potential ‘human interest’ story for stringers, publicising the achievements of women from influential or political families during festive occasions in villages helped maintain the caste hierarchy.

[This is an edited extract from Bhargav Nimmagadda’s book ‘Stringers and the Journalistic Field: Marginalities and Precarious News Labour in Small-Town India’. The author gratefully acknowledges the inputs he received from the University of Hyderabad faculty members senior professor, Vinod Pavarala (UNESCO Chair on Community Media), and professors Kanchan Malik (Communication), and Sheela Prasad (Regional Studies) at various stages of the research. Usual disclaimers apply.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.