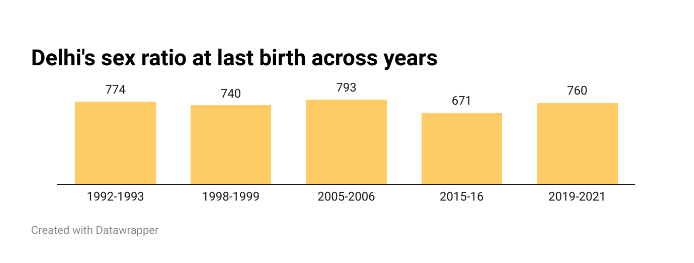

The sex ratio of the National Capital Territory of Delhi has been consistently skewed over three decades, shows a BehanBox analysis. The reason for this lies in the Capital’s location, right in the middle of a “cultural and geographical continuum” where gender preferential practices are rampant, say demographic experts.

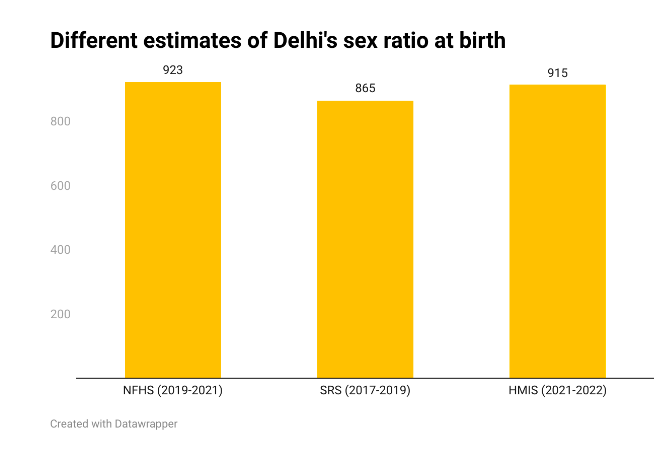

Delhi’s sex ratio is 913 women per 1,000 men, as per the latest and fifth round of National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) conducted between 2019 and 2021. Its sex ratio at birth – a different figure because it is an estimate of all births during the last five complete calendar years – is 923 girls born per 1,000 boys.

The states and UTs with worse sex ratios currently are Chandigarh (917), Haryana (926), Punjab (938), and Jammu and Kashmir (948).

Delhi’s numbers are lower than the national average for both, the sex ratio (1,020:1,000) as well as the sex ratio at birth (929:1,000). And this is despite an almost 10% improvement over the NFHS-3 number, 2005-2006, when the sex ratio was 814:1,000 and the sex ratio at birth 840:1,000.

Globally, the natural sex ratio across populations is approximately 952:1,000, the World Health Organization estimates. Numbers that fall below this are considered indicative of gender bias, and the reverse is true too – progressive and gender-just regions tend to report more equitable sex ratios.

Delhi features among the bottom five states and union territories on sex ratio at birth according to every major data source we analysed – the Census, NFHS, the Sample Registration System (SRS), an annual, national and sub-national demographic survey on health indicators, and the Health Management Information System (HMIS), a government-run, web-based monitor.