‘We Rarely Connect The Social Worlds Of Migrant Women Workers’

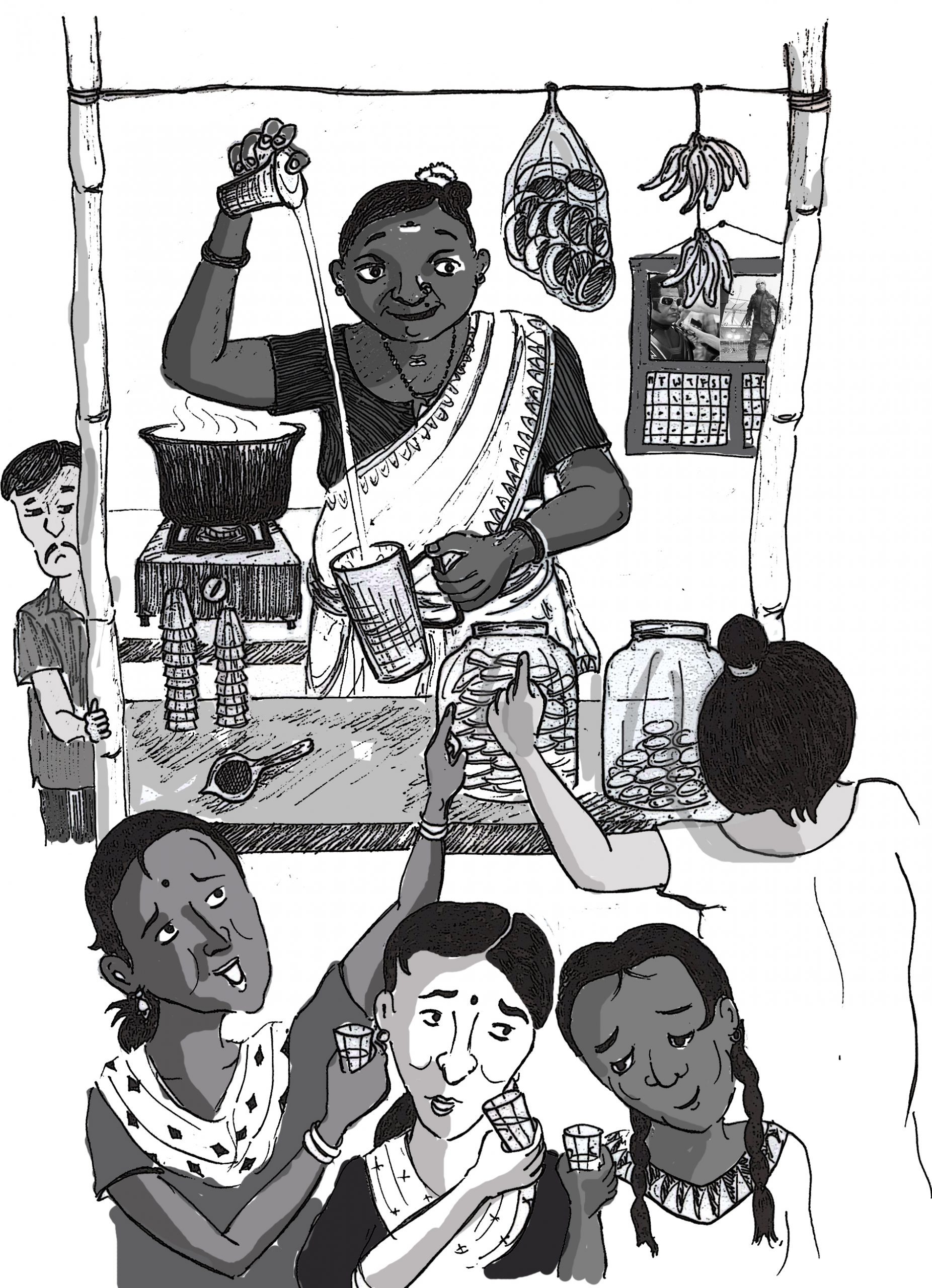

‘Mobile Girls Koottam: Working Women Speak’, released in 2021, documents the real-life conversations between gender and labour rights scholar Madhumita Dutta, radio podcaster Samyuktha PC and five Tamil migrant women workers employed at a mobile phone assembly factory in Kanchipuram, 74 km south of Chennai. Scripted like a play located in ‘Muthu’s Room’, the book’s dramatis personae are vibrant young women who have left their homes in rural Tamil Nadu – and oppressively patriarchal rules of behaviour – for cities to explore livelihood opportunities and the possibility of freedom. Evocatively illustrated by Madhushree, and published by Zubaan, the conversations – originally recorded for a radio podcast – are light, warm and rich with observations about society, gender discrimination and labour rights. We speak to Dutta, currently assistant professor of geography at the Ohio State University , about her experiences recording this unique work and where the story stands today.

Your book offers some rare and intimate insights into the world of migrant women workers and how the whole migrant experience liberates them from oppressive social rules but also leaves them vulnerable in other ways. What drew you to the idea?

This book is part of a larger story. In 2005, when the government of India passed the Special Economic Zones act, there was this whole movement around the country on issues of land and labour. Tamil Nadu was very much a part of this and there was serious concern about land dispossession, labour rights, new work sites and so on. Several states, such as Maharashtra, had very interesting histories of political mobilisations around caste, industrialisation and land relations.

This book has to be seen in the context of the political economy of Tamil Nadu and the rest of India. In Tamil Nadu, gender and caste and labour relations play out in a very particular way. I was a part of the movement in Tamil Nadu as a social activist, not an academic at that point of time. I was also observing how people were being impacted in different ways and the acceptance of and resistance to a national economic policy.

When the special economic zones (SEZs) were established, this particular mobile phone assembly complex came up in Kanchipuram, which had several supplier factories. And there was a particular gender dimension to how these factories were set up, requiring a particular kind of labour. This is not uncommon because this is something that has happened in Latin America, especially around the Mexico border, and Southeast Asia in the electronics sector. In a sense, these women are local but also part of a very global workforce.

You said that there is a certain global specificity to the background from which these women come. What are the common threads?

Of course there is the class factor but also links in terms of land. Many of these women and their families were part of the agriculture-based land economy. The shift produces a certain kind of work and labour relations. For instance, in this case, the women who came to work in the Nokia factory were not all first-time workers. They had been working all their lives, at home, in the farm, mills, or a part of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme ( MGNREGS). But here they came into what is seen as the modern workplace. And this is not casual work. This is true of similar setups in other parts of the world.

So it was interesting for me to see what was happening in the context of India. Who are these people populating these zones? What does this work mean for these women, in terms of their own personal circumstances, of labour in the larger sense, and especially women’s labour? What about the politics, being in this sort of a work site, where they encounter global capitalism? What does it mean in terms of living together not just as workers, but as young women with all sorts of dreams and aspirations?

I was drawn by the conflicting politics. There are the conversations in the book – which were also part of a radio podcast – but there were other conversations as well. But the podcast really captures the heart of these exchanges between me and the women – ordinary conversation with extraordinary insights.

Though most of the conversation is in the form of light banter they deal with hard social and political truths. A large part of the discussions revolved around the question of all-male spaces like tea shops where women cannot idle or unwind like men. The women are so agitated about this they want to set up all-women tea shops. Were you surprised by the response?

Not really. It was about individual experiences, but the idea was collective. The whole conversation started with Muthu saying ‘I’m so tired, I’m coming back from work, but I can’t stop at the tea stop and drink chai’ and the others said, ‘Yeah, we have the same experience.’

And then they started talking about the tea shop. What is interesting is that some of them said it’s slightly easier to go to a tea shop in their villages than in urban spaces. So what is it about these spaces? The cities give us some sort of freedom, but on the other hand, they really restrict our movement.

There’s a dichotomy there and in that moment, one of us said, ‘Hey, what about our own tea shop?’ And that really sparked [the idea], yes, why not? And then, look if we have a tea shop, then how is it going to be different, how do we change things?

So this feminist tea shop – the women don’t call it that, urban people like you and me do – would it be a space for women, but will men be allowed? We want to be equals too so it is not about the exclusion of men. More like getting into a bus and there are seats for men and women.

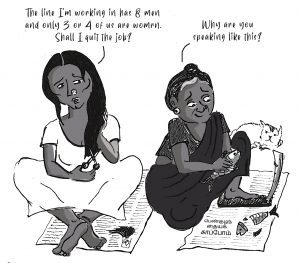

One of them suggests that maybe we could have a tea shop divided into two halls , one for men and another women, but men may cross over on invitation. They are thinking in terms of a comfortable camaraderie. Was there camaraderie between men and women on assembly lines, where the sex ratio you say is 8:3?

There was quite a bit of camaraderie between men and women and because they were of similar age, this was also sometimes sexual. But there were also friendships and support and solidarity, though not always. And one should not paper over caste and other divisions.

What I was quite interested in was the everydayness of these friendships, the emotional bonds, the kind of care that developed between the workers. So, they’re working and they have a certain consciousness of that work and the labour process. And through that labour process and consciousness, what kind of relationships are they building? Not just between capital and labour, but also between people.

There were also their social relations outside the shop floor. I have remained friends with all of them even till today and we are still doing a lot of work together. There are some who are not on the podcast like Beula who worked in the factory and was going through some personal crisis. She’s a single mom. The workers in her factory came together, found her a house. So you can’t quite separate this sort of a workspace from others.

Oftentimes we go to a work site and just look at that exploitation or whatever else is going on there without really connecting the social worlds.

The workers come from families that impose orthodox rules for social behaviour for women – on mobility, ritual purity, interaction with men. One of them is actually locked up when the family goes out and another is chaperoned by her brother every time she leaves home. But these families must be aware that the women are not controlled by these rules when they work and live in cities. Are they okay with this disconnect?

They are aware of that contradiction. Muthu, for instance, spoke about this: I am working night shifts, working with men, coming late, going to the market but when I go home, these are the restrictions. She comes from this place known for caste violence and herself belongs to a powerful caste where there are restrictions on women, this sort of sexual tension. She is of an age when women have to be married, have to be protected. But then there is also economic need and then the family decides that, okay, she needs to go and work in this space.

These issues are also temporal and spatial – Muthu says her mother says ‘When you are in a city and outside our protection, there are these leniencies but when you are here, this is how it will work. You do what you want when you are not home.’ So Muthu laughs and says okay, in that case maybe I should quit because I have all these men standing next to me. And the mother says: ‘No, no, no, I trust you. I trust you, but don’t do it here.’

There is another fascinating subject the women bring up – the very discriminatory, pan-Indian rules about women’s right to leisure, at home and at work. They talk about not being allowed to sleep late at home unlike their brothers, lounge around even on a holiday, leave their hair uncombed.

It is not just pan-Indian, it’s international. One is reminded of what Audrey Lorde, the Black radical poet-feminist, said about women’s need for self-care and leisure: “caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare”. Therefore, the desire for rest, time for leisure among the women in Muthu’s room was a radical act.

In the world of labour, for women there is so little time for self-care and self-preservation, to relax and just to take care of oneself without feeling guilty. This was important to the women in Muthu’s room, they worked standing for eight hours on assembly lines everyday. And even though the factory was air-conditioned, which some would argue is better than working in the fields under a hot sun, the work intensity on the assembly required continuous motion of hands, standing for eight hours with very few breaks. And of course the stress of work, the targets to be met as all this is connected to the just-in-time global production chain. Most of these electronics factories globally have a preference for women of a certain age group whom they want to hire, it’s very gendered.

When they wanted to get a break, there was no place for the women to sit and relax. There was a rest area, but it was meant only for pregnant women. So the workers, both women and men, used toilets to get a quick break. They would go sit in the restrooms for a bit.

As for women’s homes, even the desire to sleep an extra hour would raise a lot of questions like: what will people say, what about when you get married? etc And one sees that the unequal gender relations at home get reproduced in other places including workplaces.

They also seem to be monitored very closely for efficiency. But these women are not casual workers, they are employees and have certain benefits. They are also unionised, aren’t they? Could they not assert their rights?

Initially there was something called a workers committee. And, they kind of managed to get concessions or some sort of relief on some smaller things – wages, work conditions etc. At some point, they managed to form a shop floor union with the help of CITU and interestingly, the leadership of the union was all-men though the factory was mostly women.

I had once asked the men leaders why they didn’t have women in the leadership team. They said, ‘Oh, women don’t have time and they can’t come for these kinds of meetings – because we are talking to the management and it could be anytime, anywhere’. And then, finally they said, ‘Well, women gossip’. And I said, ‘Maybe gossip is how you organise and who says men don’t gossip?’.

In 2013 when the union was set up, it was a huge struggle. But they actually had a good negotiation on wages etc. But pretty soon after that, the factory shut down.

The factory had these ridiculous Five Sigma rules about sanitary pad vending machines: a woman worker who needs a pad unexpectedly has to sign a form before an assigned supervisory team to get a coin. And if she stocks pads in her locker and needs to access it in the middle of a workday, she has to be accompanied by a security guard.

The irony, sheer irony of it. There is this whole management thing, this Five Sigma, and then there are the women’s bodies.

The work was intense, it affected their mind and body and some said they would have liked to leave. But in 2014 when the factory was actually shutting down and they asked people to take voluntary retirement (VRS) , the women actually said they didn’t want to go back to their villages. They didn’t want their old life back in the villages. There was a little bit of money they had and if they didn’t get the VRS, the battle could have gone on. But they didn’t know if they would get that money so they took it.

However, they were clear that they didn’t want to go back. So for months, especially in Muthu’s room, the women did not go back. They stayed on, paid from their savings for the rent and food. And they went around factories looking for work. Some found it, some did not, others found contractual work they did not like or paid less.

At no point of time did they not understand the hardship and the brutality of this kind of work. But there were these complex relations that they had to deal with at home. So they were trying to make a decision. And I think that ability to do that also came from living independently and making decisions for themselves, say on how to spend money the way they wanted. Of course, the bulk of the money went back home to take care of families. And they were always connected.

They just wanted to be themselves as young women of a certain age and do certain small things, nothing big. They were also saving money, not necessarily for dowry or marriage because that is what everybody thinks. Just for themselves, to have a certain economic autonomy. They were also buying chit funds or running chit funds within the factory. The management was really upset but who could stop them. They would do stuff, even in the locker room – sell something, run some sort of enterprise.

Kalpana is one of the strongest characters in the book, from a different league altogether. She talks about relationships with men, premarital sex, contraception with confidence and conviction. Did her voice stand out for you?

Oh yes, Kalpana is really my closest friend and even now we are on WhatsApp every day. She is quite extraordinary in the way she thinks about the world. She comes from a large Adi Dravidar (Dalit) family where the father abandoned them, nine children, when Kalpana was still very young and in school. So she took charge of her mother who was at that time pregnant and took care of her siblings. She is somebody who has sort of seen what life is all about in the harshest possible way, but also in a very political way.

She is like ‘I’m oppressed and all this bad stuff is happening to me but I can also change things’. When she was young, she came in contact with certain social organisations which were teaching Ambedkar’s writings and she was very influenced by them, and also the feminist and labour movements. She became very politically conscious of caste, gender and labour relations. She started connecting her experience to this larger political, ideological context. She’s what Gramsci would call an “organic intellectual”.

At any of those big gatherings if you give her a mic she will just take off. She’s quite something – with the VRS money that she got she set up a shop, bought a camera, she set up a studio in her village where everytime you need a passport size photo for some government work you have to go to town.

You said you were planning something interesting with the women. Can you share some details with us?

I must mention Samyukta here, who likes to be called Sam. This radio podcast couldn’t have been possible without her. She’s an extremely creative person, an artist and it was towards the end of my fieldwork that I started working with Sam.

So Sam came as my field interpreter but she was more than that. And it was really her idea. I wanted the women to converse with each other, rather than me asking a question and them responding. I was wondering how we would get all of us talking. And, Sam at that time was doing a different radio podcast with her sister and friends, Radio Potti. She said, why don’t we do that and see what the women think. And then we had all these conversations in the room and it’s in the book.

And now Sam is actually pulling together a play based on this, working with a few professional Tamil actors. And this was something that we had talked about when we used to hang out in this room, that apart from doing a radio podcast, how do we take this to the villages and homes? Because the women were keen that what they were saying be heard by their family and friends. We had thought, okay, we will do a play. And a script was written.

The play never happened because the factory shut down. And I was still a PhD student. But now after six years, we have all come back together. And since last November, we have been meeting over WhatsApp, talking about the play. Some of the women from the earlier time are part of the conversation in the making of the play with Sam and the actors.

The play will happen, likely by the end of July. The first couple of shows, we are going to do it in Chennai, in the fishing villages where we had been working. It’ll be in Tamil, actually Tamil English or ‘Tanglish’ as we say.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.