Bulli Bai: How State Inaction Has Emboldened Cyber Harassment Of Muslim Women

[Trigger Warning: This article contains some disturbing accounts of harassment and violence against women,which might trigger unwelcome and distressing memories or thoughts. We advise readers to use their discretion before reading.]

“I expected this would happen again. It had to; the police hadn’t taken any action,” said Fatima Zohra, 26, a lawyer, who has been “auctioned” over virulent digital platforms twice over the last six months.

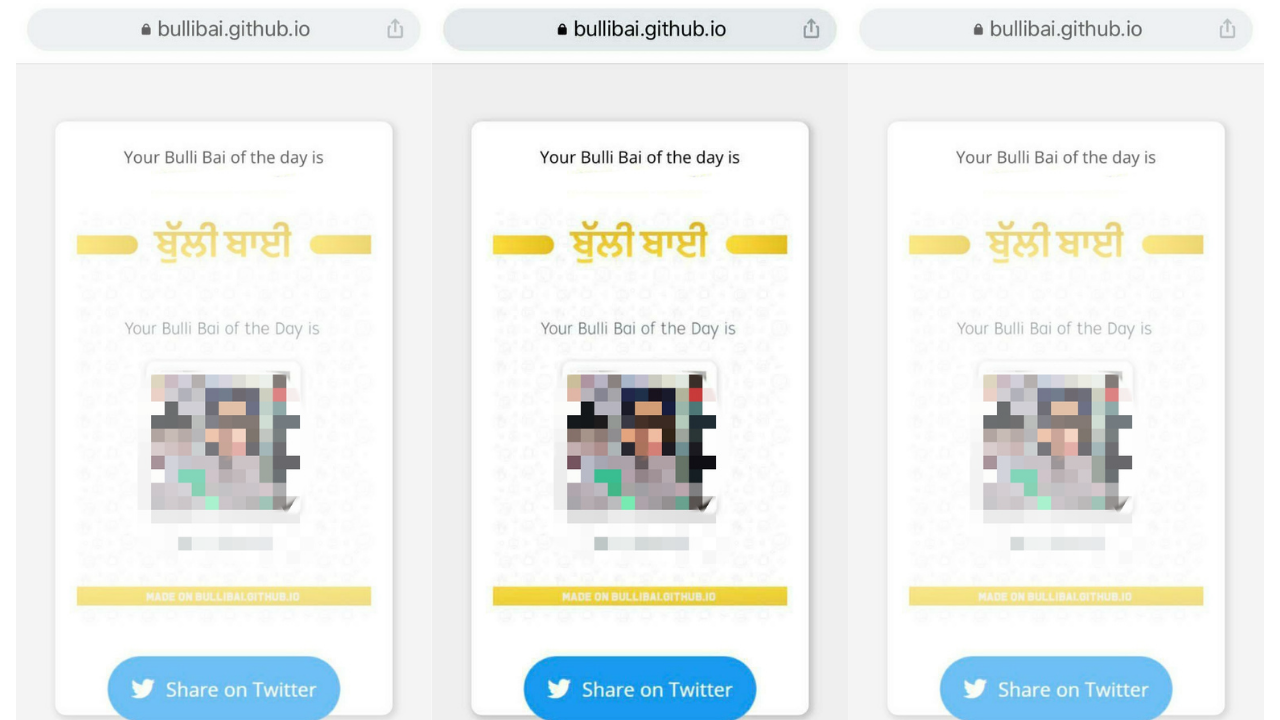

Zohra is among the 100 Muslim women whose names featured on the Bulli Bai app that surfaced on 1 January, 2022. The app, hosted on GitHub, an open source code hosting platform, used images and Twitter handles of Muslim women without their permission and put them on “sale” as the “Bulli Bai” of the day. (The word bulli is used as a pejorative for Muslim women in Punjabi and bai is a form used to address women.)

The Twitter handle of the corresponding name described it as a ‘community-driven open-source app by Khalsa Sikh Force’.

Among the 100 Muslim women whose names appeared on the app are Nobel laureate Malala Yousufzai, veteran activist Khalida Parveen, Fatima Nafees, mother of the missing JNU student Najeeb Ahmed, journalists, activists, a radio jockey, a prominent actor, historians and so on.

The same day, Ashwini Vaishnaw, the Union Minister of Electronics and Information Technology, tweeted to confirm that the creator of the Bulli Bai app had been blocked by GitHub.

GitHub confirmed blocking the user this morning itself.

— Ashwini Vaishnaw (@AshwiniVaishnaw) January 1, 2022

CERT and Police authorities are coordinating further action. https://t.co/6yLIZTO5Ce

This app is strikingly similar to the Sulli Deals app, hosted on GitHub in July 2021 and used to “auction” over 80 prominent and vocal Muslim women. Multiple FIRs had been registered by the women whose names and photos were put on the app but six months on but there has been no progress.

Those behind the Bulli app, say women, were clearly emboldened by this inaction against the flagrant harassment of women on communal lines over digital platforms. “Many of us wouldn’t have had to go through this trauma again had the authorities taken action in the first instance. They (perpetrators) enjoy complete impunity,” said Zohra.

When her name had figured in the Sulli Deals, Zohra had filed a complaint at the Powai Police Station as well as the cyber cell under Mumbai Police. But no FIR had been registered in the case. The Mumbai Police had sent notices to GitHub, GoDaddy and Twitter demanding details of the app’s creators, their website and accounts. The platforms refused to provide these details and demanded a subpoena instead.

This time, however, the wave of public outrage and revulsion has nudged state governments and police into action. On January 6, the Delhi Police arrested Neeraj Bishnoi, 21, from Assam. A second-year B.Tech student at the Vellore Institute of Technology, Bhopal, he is believed to be the creator of the Bulli Bai app. The police have also taken possession of the device believed to have been used to create the app.

Investigations across states

At least three First Information Reports (FIRs) have been filed in the Bulli Bai case, including those in New Delhi, Mumbai and Hyderabad.

On January 1, Ismat Ara, a journalist at The Wire, whose name and photo had featured on the app, filed a complaint with the cyber cell of the Delhi Police under Indian Penal Code (IPC) sections 153(A) (promoting enmity or hatred between communities on the grounds of religion), 153(B) (imputations, assertions prejudicial to national integration), 354(A) (Assault or criminal force to woman with intent to outrage her modesty), 506 (punishment for criminal intimidation) and 509 (word, gesture or act intended to insult the modesty of a woman). The complaint also referred to sections 66 (dishonest and fraudulent acts under computer related offences) and 67 (publishing or transmitting obscene material in electronic form) of the Information Technology (IT) Act.

UPDATE: A complaint has been filed by me with the Cyber Cell of Delhi Police for immediate registration of FIR and consequent action against people behind the auctioning of Muslim women on social media. #sullideals #BulliDeals @DelhiPolice pic.twitter.com/oX3ROLEgv1

— Ismat Ara (@IsmatAraa) January 1, 2022

A day after her complaint, the Delhi Police registered an FIR at the cyber police station of Southeast Delhi under IPC sections 153A, 153B, 354A, and 509. There was no mention of the IT Act in the FIR.

The Mumbai Police filed an FIR against unknown persons at the cyber police station of western region after receiving a complaint from Sidrah, another woman listed on the app. The FIR was registered under IPC sections 153(A), 153(B), 295(A), 354(D), 509, 500 along with section 67 of the IT Act.

Four persons have been arrested so far for their involvement in the creation of the Bulli Bai app by the Mumbai police. This includes engineering student Vishal Kumar Jha, 21, and a Delhi University student Mayank Rawat, 21, hailing from Uttarakhand. The police also arrested Shweta Singh, 18, allegedly the “mastermind” behind the crime. The Mumbai Police claimed that she was operating three accounts related to the ‘Bulli Bai’ app.

In a press note dated January 5, the Mumbai Police stated that Jha, her co-accused, had opened an account in the name of “Khalsa supremacist”. He is also believed to have used fake Sikh names in the accounts operated by the others. This could have led to communal tension between two groups, the police release stated.

The main accused woman was handling three accounts related to 'Bulli Bai' app. Co-accused Vishal Kumar opened an account by the name Khalsa supremacist. On Dec 31, he changed the names of other accounts to resemble Sikh names. Fake Khalsa account holders were shown: Mumbai Police

— ANI (@ANI) January 4, 2022

On January 3, the Hyderabad Police too filed an FIR at the cyber crime police station against unknown persons under section 67 of the IT Act, and IPC sections 354D and 509 based on the complaint they received from human rights activist Khalida Parveen.

While Parveen, like many other women whose names were listed on the app, had been insisting that trafficking charges be included in the FIR against those involved, the Hyderabad police refused to include those charges. “There is no actual trafficking. It’s mentioned that they are for sale, but all of this happened over an app virtually,” KVM Prasad, Cyber Crime Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP) told The News Minute.

Anas Tanwir, an advocate at the Supreme Court and founder of the Indian Civil Liberties Union, believes that Indian laws on trafficking are inadequate. “Our laws envisage trafficking only as involving a physical sale and transfer of an individual. The absence of a physical sale makes trafficking laws inapplicable. However, these online auctions outrightly promote trafficking and should come under the purview of the law,” he said.

‘It was traumatising’

This is not the first time that Muslim women have had to encounter police and legal systems, which have left them exhausted.

In July, 2021, when the Sulli Deals app surfaced, multiple FIRs were registered following complaints by the women whose names and pictures had appeared on the app. Seven months on, no progress has been made in the investigation of the case by the police.

On July 6, An FIR was filed after UP police received a complaint from Hana Mohsin Khan, a pilot, under sections 66 and 67 of the IT Act and section 509 of IPC.

Filed an FIR.

— Hana Mohsin Khan | هناء (@girlpilot_) July 7, 2021

I’m resolute and firm in getting these cowards to pay for what they have done.

These repeat offences will not be taken sitting down.

Do your worse. I will do mine.

I am a non-political account targeted because of my religion and gender.#sullideals pic.twitter.com/mvt20VWPqp

On July 8, the Delhi Police had filed an FIR based on a complaint received on the National Cyber Crime Reporting portal under section 354A of the IPC. Following this, the Delhi Police had sent notices to GitHub asking the platform to share relevant details.

In Kolkata Noor Mahvish, a law student, whose name and picture had appeared on Sulli Deals, had to go through a “harrowing” experience to get an FIR registered.“I had gone to file a complaint around 8 July. Despite having provided them with screenshots and all the necessary details, I had to explain everything over and over again,” she said. It took Kolkata Police almost a month to register the FIR, Mahvish told Behanbox.

Mahvish kept following up on her complaint over the telephone. Each time she was told that the police have not found anything substantial and that she would be informed if there were updates. Mahvish had also visited the police station multiple times to get the FIR registered. “I was told at least twice that the officer in charge was on leave and asked me to come another day.”

When the officer finally spoke to Mahvish, he suggested that she reset her profile as private. “He asked me that if someone did this to Shahrukh Khan’s photographs, could they have done anything about it?”, she recalled. The app got her unwanted attention, she said, and she would get messages about being spotted in public places by random Instagram accounts.

“It was so traumatic and exhausting. It has been six months since then and I have received no updates from them,” she said.

Zohra does not believe that the women will get any justice. “Justice is a far-fetched dream for Muslims in India. The system is apathetic towards our sufferings. We have been auctioned and treated like sub-human individuals. Yet suo moto cognizance of the case was not taken and the onus to act was put on the women,” she said.

Quratulain Rehbar, a Kashmiri journalist, who was featured on the app, does not plan on filing a complaint. “ There is a total lack of trust in the system. I do not know what to do because I am not sure how the system will deal with women’s issues. It’s a tiresome process and I do not want to put myself under any pressure,” she said. Following the abrogation of Article 370 and the revocation of Kashmir’s special constitutional status, the government disbanded the Women’s Commission in Srinagar. This has created a gap between those who are seeking gender justice and the justice system.

The apex court has the power to take suo moto cognizance on such cases, Tanwir told Behanbox. “There are no precedents of suo moto cognizance by courts in such cases because these are unprecedented cases and are unheard of in civilised societies. However, the courts have the power to do that,” he said.

On the question of the onus being on the affected women to take action, Tanwir said, “all women need not file complaints individually. The police have the power to take suo moto cognizance and act once they receive information on a cognisable offence.”

Growing online toxicity

Women have reiterated often on various platforms that the auctions must not be seen as isolated incidents but as part of a larger ploy to “dehumanize, sexualize and intimidate” influential and vocal Muslim women. Behanbox had earlier reported on the vicious pattern of cyber sexual violence faced by Muslim women.

On December 29, 2020, journalist Sania Ahmad found herself tagged in a poll that asked Twitter users to choose one woman for their “harem”. To her horror, the options included her name and that of Sania Syed, a screenplay writer. The poll, created by Twitter user @mithilasher, had received about 100 responses by that time.

Despite having repeatedly reported the poll, it stayed on Twitter for one entire day, Ahmad told Behanbox. “During these 24 hours, I saw graphic comments left by multiple users including those about chopping our heads off and using them to decorate their walls.”

While the poll was taken down, the abuse and harassment continued. Ahmad recalls being added to a group titled ‘Sania’s E-Milk’ on Twitter where her and Syed’s pictures were morphed onto pornographic images and shared. “I filed a complaint with the cyber police in Delhi but nothing happened. No action was taken,” she said.

In May 2021, a YouTube channel called Liberal Doge, live-streamed an online auction of Muslim women from India and Pakistan. Ritesh Jha, the creator of the channel with more than 85,000 users, egged users to “rate” and “auction” women whose Eid photographs were picked from their social media accounts without their consent.

In the same month, a Twitter handle named @Sullideals had uploaded a morphed picture of Ahmad as its header image. She had been tagged in it. Ahmad reported it to Twitter several times but no action was taken.

Ahmad continued to face abuse and harassment from social media users who identified themselves as “TRADs (or traditionalists)”. Most of them were aged between 18 and 24, with some being as young as 15, she said. “These teenagers and youngsters are extremely proud of belonging to upper castes and believe that the Indian right-wing is not engaging in enough anti-Muslim activities. They would send me rape threats and sexually graphic messages about mutilating the bodies of Muslim women,” she said.

TW: You want to understand the scale of the Trad filth we have had to suffer? Here are some examples of what we have been made to go through.

— Sania Ahmad (@SaniaAhmad1111) January 4, 2022

Thread: (1/4) https://t.co/Lh1IPT5t5U pic.twitter.com/ANSbiM5FcX

About 45 days later, in July, Ahmad found her name and photograph on the Sulli Deals app. “The Twitter handle had remained functional all this while. We kept reporting it. It didn’t matter if my morphed picture was on the profile; the profile was suspended only after there was uproar on social media against the app,” she said.

Disillusioned with the police and their lackadaisical response in her previous complaint, Ahmad decided to send a legal notice to Twitter demanding that the accounts involved in the Sulli Deals be permanently suspended. Seven months on, Ahmad has yet to get a response.

On November 27, 2021, a group of men were “auctioning” body parts of women in a room on Clubhouse, a voice-based social networking app. This was revealed when a Twitter user shared a video of the discussion.

“We have been talking about it since 2020. But nobody listened. Now it has blown with over 100 women becoming targets of this abuse. And this will keep happening until the whole ecosystem is shut down,” said Ahmad who continues to be harassed on Twitter.

@DelhiPolice This Giyu, when I called him out for bidding on Hasiba, changed his handle name and picture to that of a Muslim and posted this. He was sending me warnings last night for a 'Bulli Bai 2.0' also. https://t.co/7nF7pWIELe pic.twitter.com/6Rhq7aCUeZ

— Sania Ahmad (@SaniaAhmad1111) January 6, 2022

Khushboo Khan, a Delhi-based journalist whose name appeared on the app, believes that this toxicity will multiply in the coming months. “Today they are auctioning us using our pictures; if they are not stopped they can do anything tomorrow to silence us. They can morph our pictures and circulate them to the public. Bulli Bai happened because no action had been taken previously,” she said.

Hate content and its ecosystem

Hyderabad activist Khalida Parveen is of the view that the real culprits behind these toxic campaigns are those spreading communal hate elsewhere. Her name, she pointed out, featured in the “auction” list only a day after she had run a successful online campaign demanding the arrest of Narsinhanand Saraswati, the priest who led an assembly in Haridwar calling for genocide against Muslims.

“Our campaign had gained a lot of traction. It had even caught the attention of international media. And it is against this backdrop that the Bulli Bai issue must be seen. It was an attempt by the Hindutva forces to divert attention while simultaneously threatening Muslims who raised their voice against them,” Parveen told Behanbox.

Exactly a day after the Bulli Bai app caught public attention, a video of Narsinhanand started doing the rounds of the social media, where he is seen making derogatory remarks about Islam and Muslim women.

"For lobbying they send they Musalmanis (slur for Muslim women) to sl€ep with influential journalists and politicians."

— Mohammed Zubair (@zoo_bear) January 3, 2022

This is a day after the Bulli Bai scandal. The fact that he can openly give gen'ocidal & misogynist speech is alarming.pic.twitter.com/xxNxqX3zmG

The hate campaign against Muslim women in recent times goes back as far as the women-led protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and National Register of Citizens (NRC) in 2019, according to Zohra.

“When they (the Hindu right-wing) saw Muslim women leading one of the largest resistance movements in recent times single-handedly, they realised our power. Following that they started abusing and defaming us in an attempt to scare us into silence,” she said. “It has been pointed out on multiple occasions that the Prime Minister follows abusive handles that give rape threats and use derogatory language. These handles see it as an endorsement. Secondly, religious leaders and political leaders use the same demeaning language for Muslim women and get away without any consequences. This has led to normalisation of such hateful speech.”

Khan traces the normalisation of violence against Muslim women back to the Gujarat pogrom of 2002. “It has become a norm that Muslim women are attacked whenever the majority wants to silence and suppress the voices of the Muslim community. If you see the Gujarat pogrom or the Muzaffarnagar riots, this is what they have done.”

Tanwir believes that the fact that these individuals are inspired by hate assemblies cannot be ignored. “The TRADs and Hindutva ecosystem enjoy impunity. These 18 and 21-year-olds cannot be taken lightly. The police must look into and investigate the conspiracy angle.”

‘It is not our shame’

“I want to tell the perpetrators that the shame is not ours, it is their own. It is disgusting that they would resort to ‘auctioning’ a senior citizen like me. Today, the entire country is spitting on them. We will fight this politics of hate constitutionally,” said Parveen.

Despite having been subjected to repeated harassment, Ahmad refuses to be cowed down. “These are means of silencing us and sending a message to the entire community that if you raise your voice this is what we can do to your women and this is what we can reduce you to without any consequences. But I refuse to be intimidated by this lot.”

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.