Women Yet To Cross Gender Barriers In India’s Agricultural Markets

- Meenakshi Kapoor

Lassu Ben, 38, is an outspoken and resolute woman but even she sometimes hesitates to trade with the men at the local farm market. ‘Bahas mat karo (don’t argue)’ is a snub commonly thrown at this farmer from the Rabari community, from Nayatvada village of Radhanpur block in Gujarat’s Patan district.

“If I were a man, it would have been easier,” says Lassu Ben. Before they were married, her husband Sunda Bhai Rabari was a farm worker. Then Lassu got some land from her parents and bought some more. Today, the couple together own 6 bighas of land (1 bigha = 0.16 hectares). Lassu also tills 23 bigha on bhag (sharecropping) basis.

“The landowners here vie for a share-cropping arrangement with Lassu. She gets good income for the owners,” says Sejal Ben Rabari, a mahila kisan sakhi (friend of women farmers) who works with the Working Group for Women and Land Ownership (WGWLO), a Gujarat-based network focussed on women’s land rights.

But Lassu is a rare case of a woman who participates in all aspects of decision-making in agriculture, from production to marketing, in Gujarat or any other part of India. Few women farmers access the mandis (markets) run by the Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMC).

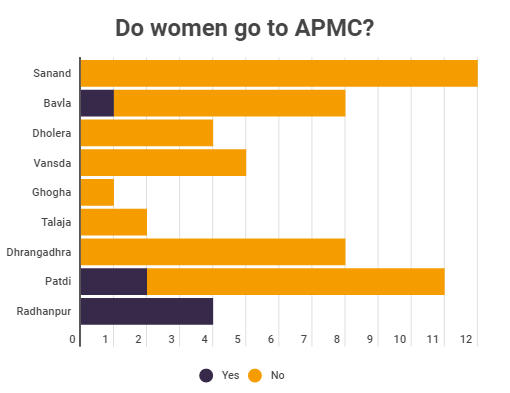

In March 2021, BehanBox undertook a survey across 18 villages, seven blocks and five districts of Gujarat to study women’s participation in agricultural marketing. We found that gender prejudices and current agricultural policies have kept women out of the markets.

Of the 55 women we interviewed, only seven (13%) had access to the state’s mandis. And even those who go to the market to trade either take male family members along or schedule their visits during lean hours when fewer men are around. Not only that, the men in their family are often taunted for their presence in the market.

Women’s involvement in agriculture has increased, their ownership of land is also seeing an uptick. However, this may not improve their bargaining power and the exercise of free choice in the sale of their produce, if market policies are not amended.

Gender discrimination in the market, however, began to be debated only after the government passed, in September 2020, three farm laws that could change the face of Indian agriculture. One of these was the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020. The Gujarat government passed an ordinance amending the Gujarat Agricultural Produce Market Act in May 2020, followed by the passage of an amendment in the assembly in September 2020.

The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 bypasses the state-controlled APMC regime. In doing so, it not only denies states the right to levy fees on the purchase or sale of produce outside the APMC-run mandis but also does away with the state oversight of agricultural trade. This could put an end to a transparent price discovery system and affect the interests of women farmers, most of whom do small and marginal agriculture and tend to sell their produce outside the mandi.

“We started talking to women about the issue to understand how this new law would affect them,” said Shilpa Vasavada, a member of the Mahila Kisan Adhikar Manch (MAKAAM), a nationwide informal forum for women farmers’ rights, and the WGWLO network.

Women have more agency in tribal pockets

Of the 55 women interviewed across five districts, four were from Patan (Radhanpur block), 19 from Surendranagar (Patdi and Dhrangadhra blocks), three from Bhavnagar (Talaja and Gogha blocks), 24 from Ahmedabad (Dholera, Bavla and Sanand blocks) and five from Navsari (Vansda block, which is a tribal pocket).

Of the seven women who said they visited mandis, four were from Patan, two from Surendranagar and one from Ahmedabad.

“I expected an even lower number,” said Dr Itishree Pattnaik, Assistant Professor at the Gujarat Institute of Development Research, Ahmedabad, reacting to the findings of the survey. Vasavada too agreed that social norms in the state discourage women from trading in the markets.

“While women not accessing the market is observed across the tribal and non-tribal areas of Gujarat, the trend is rooted in the societal norms of the non-tribal belt, which comprises North Gujarat, Kutch and Saurashtra region,” says Vasavada. The survey established this too. The responses from women in the non-tribal districts showed strong links between their lack of control over the produce and regressive social customs.

‘Only men go’

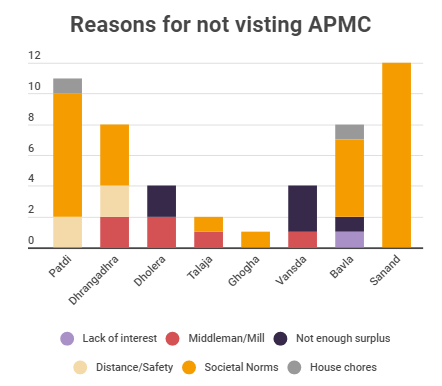

Why do women refrain from visiting APMC mandis? Societal norms, the presence of middlemen and lack of enough surplus to sell were some reasons stated by the women farmers. Of the total 50 responses (some women provided multiple reasons), 32 were along the lines of “Only men go to mandis” or “Women don’t go there”.

Geeta Ben Rabari, the vice-chairperson of Bechraji APMC in Mehsana district, provides another insight into how patriarchal communities discourage women from participating in agricultural trade: They shame the male relatives of women who visit mandis. “Mahila mandi aati hai, toh sab us ghar ke purush ko taane marte hain (If women come to the APMC mandi, the men of their household are jeered at),” says Rabari.3

The 32 responses clubbed as ‘societal norm’ in the chart above were from non-tribal areas. Two women cited ‘house chores’ as the reason why they avoided going to mandis but Vasavada reads these as an extension of entrenched social norms.

“They (women) may rationalise it (not going to the APMC) with statements like ‘Ghar pe kaam hai (I have work at home)’ or ‘if I go to the mandi, who will take care of the chores.’ But the norm is so deeply internalised that women don’t realise that going to the APMC or being involved in marketing is a possibility,” says Vasavada.

During a group discussion in Dhrangadhra, women farmers chuckled and shrugged off the idea of going to the market with “Hamara wahan kya kaam? (what work do we have there)”.

Many factors at play

Though women in tribal communities have more agency in their homes, this was circumscribed by other factors that affect agricultural trade, say both Vasavada and Pattanaik. The amount of land owned, crops raised, the surplus generated, the degree of control tribal communities have over resources, and the place of farm earnings in household incomes — all these come into play in this context.

The results of the survey confirmed this. Three of the five women from tribal communities we interviewed in Vansda said that they do not have any surplus to sell in mandis. They do sustenance farming on small land parcels of 1-2 bighas.

In all, eight women farmers said that they do sustenance farming with little to take to the mandi. Most of the produce is saved for the household and the little surplus that they can spare, is either sold to those they know, middleman or handed to other farmers to sell in APMC mandis. The active involvement of farmers and their families in the sale of produce is rare when the surplus is inadequate. This was observed in Dholera, Dhrangadhra and Vansda blocks.

Intimidating distances

In Dhrangadhra block of Surendranagar, reliance on middlemen was also linked to the distance to the mandi. Women from Isadra village in Dhrangadhra would have to travel 40 km to reach the Halvad APMC. So, they choose not to.

“Dhrangadhra mein yard banega toh jayenge (Once the market yard in Dhrangadhra is functional, we will go),” several women told us. In fact, even the men here do not visit the Halvad mandi.

It is the same story in Patdi block of Surendranagar. It has a mandi but farmers prefer to go to the Unjha mandi, in Mehsana district, 116 km away, to sell cash crops such as cumin.Unjha mandi is bigger and fetches better rates for cash crops.

In the absence of surplus produce to sell, issues like distance to the mandi and travel safety tended to become more important for farmers. Farmers, men and women alike, are less inclined to go to the mandi if the expenses of hiring a vehicle, the pain of long-distance travel, risk of theft and the cost of missing a day’s work in selling the produce outweigh the earnings.

Digitisation of market deepens divide

Digitisation of the APMC mandis has put women at an even bigger disadvantage.

When in 2015, Gujarat started providing mandis with an e-market platform, 122 of a total of 210 signed up. But this may have further alienated women in the agriculture sector because many of them do not have access to personal mobile phones and the internet. A 2018 report said digitisation of markets has affected women’s ability to trade given their limited digital capabilities, social and household-level surveillance of their movement and interactions and the absence of policy support for women’s digital presence.

The APMC mandis at Bavla and Sanand went online last year at the start of the Covid pandemic. “Since then, farmers have been facing difficulty in not just registering but also selling once they are registered,” says Jagruti Ben, who was working as Mahila Kisan Sakhi with WGWLO at Sanand till the end of April.

“Most single women are small and marginal farmers. Besides, lacking the know-how of the online platform, lack of transparency and uncertainty too affects them. Farmers don’t know when they can sell. They find it difficult to wait for weeks to sell and receive money.”

Lucrative opportunities are cornered by men

Women are kept out of agricultural trade when the quantity of trade and returns is high, we observed in our interactions with the farmers. But men did not directly say so.

“They are often not educated. They may find it difficult to hire a vehicle, calculate the payment or raise an invoice,” were the possible reasons that Jitendrasinh Gohil, the Secretary of the Bavla APMC, gave for women’s absence from mandis.

The women of Radhanpur block do not fit the gender cliches implied in Gohil’s response. The Rabari women we interviewed said that only women from Rabari, the traditional pastoral community and Thakor, the traditional cultivator or small land owner community, visited the Radhanpur mandi. “Woh Thakor mahilayein mandi aati hain jinke pati sharab peete hain, aur Rabari mahilayein toh aati hi hain. Baaki samaaaj ki mahilayein mandi nahi jaati (Thakor women whose husbands drink visit the mandi; Rabari women anyway visit mandis. Women from other communities don’t),” said Lila Ben from Arajansar, Radhanpur.

Rabari women, the traditional pastoral community from India’s western states, are less constrained by gendered roles than women from other communities. However, the Rabari women of Patdi block did not go to mandis. This had to do with low quantum of produce from the small rain-fed parcels of land in Radhanpur that most Rabari women take on bhag (share cropping) in the region, says Sejal Rabari from Radhanpur.

“They (Rabari women in Radhanpur) don’t produce much. Therefore, they take care of the sale of their produce too. In other areas, large land holdings mean big produce that women are not trusted with. And a common refrain is that they ‘don’t know how to calculate’,” says Sejal.

Vasavada points out that social mobility, instead of empowering women to enter the market, holds them back. “In well-off households women are not sent out,” she says.

In her paper titled ‘The feminization of agriculture or the feminization of agrarian distress? Tracking the trajectory of women in agriculture in India’, Pattanaik says that women take on those economic activities that are left by men. When it is lucrative, the marketing of produce is generally handled by the men of the house. But when it is not, either women step in or no one does.

Take the example of Saira Bibi from Bavla. She appeared fully involved in the work of growing 40 mann (1 mann=40kg) of wheat, giving BehanBox a detailed breakup of her expenses on seeds, fertiliser, labour and renting the water pump and tractor. But she had no interest in going to the mandi because she makes very little on sales. “The rates of petrol and oil are increasing every day but the rates of wheat don’t increase,” she says with an air of disappointment.

Land ownership and access to APMC

In India, close to 75% of rural women are engaged in agriculture but only 13.96% women own land, according to the agriculture census 2015-16. In Gujarat, 16.4% women have operational holding according to the data.

Of the women who said they visited the APMC, all own land either individually or jointly with their husbands, except two Rabari women from Radhanpur who do bhag kheti (crop sharing) on land owned by others.

A 2012 study said that the lack of asset ownership compromises women’s bargaining power. However, the correlation between land ownership and access to APMC is tenuous — land ownership alone cannot ensure empowerment, women’s status within the household, customary practices, their own interpretation of their rights and the complex systems of statutory law, all have a role to play.

Of the 55 women we interviewed, twelve own land singly or jointly with husbands but only five of these go to mandis. Pattanaik’s reading of the result throws more nuanced light on the impact of land ownership as a means to increase agency and control. “Land ownership is essential, but it is only the first stage of empowerment. This realisation that the right to own land is a need beyond the level of household, that it extends to an individual, is quite recent. We are yet to see the clear linkage between land ownership and intra-house decision making.”

Passive role in the market

Two of the 29 registered traders at the Bechraji mandi are women. Geeta Ben Rabari is one of them, who goes to the mandi with her husband. The other woman trader does not participate. “Her husband is taking her place,” says Geeta Ben. This is a common scenario. Women traders, even when registered, are represented by their male relatives in mandis. Uncomfortable experiences such as Lassu’s, and the overwhelming presence of men discourage women from participating in the mandi’s businesses. The experience of a woman-led cooperative society in procuring onion in the Lasalgaon mandi in Nashik, Maharashtra is the latest example of how women are pushed out of trading.

In Bavla, Gohil tries hard to recall if any woman ever traded at the Bavla APMC but gave up. “Hongi bhi toh quiet partner hongi, unki jagah purush aate honge (if there were any woman traders, they must be passive. The men in their family must be representing them),” he says.

So, why do women register as traders then? Gohil thinks it could be linked to the availability of easy loans offered to women. Banks often run special loan schemes at affordable rates, without guarantee, for women entrepreneurs.

Geeta Ben, the only active woman trader at the Bechraji mandi, ensures that trade happens smoothly while resolving complaints from the farmers. “Main khedut hun, toh main aksar khedut ki hi side leti hun. Main pakka karti hun ki khedut khaaskar ekal mahilaon ko achha bhav mile (I am a farmer. So I support farmers. I ensure that farmers, especially single women get a good rate),” she says.

According to Vasavada, even in tribal areas (Surat, Valsad, Panchmahal, Bharuch, Vadodara, Sabarkantha, Dangs, Narmada, Navsari), in the eastern belt of South Gujarat, women access the market, not essentially the APMC mandi though, but their role is passive.

We asked a few young women in the tribal belt about what they do in the market. “Hum bas dekhte hain (we only watch)”, they said.

Lila Ben’s daughter from Godiavad village in Patdi narrates a similar experience on her trip to the mandi.

“I went to Patdi mandi with my brother once; 4-5 traders came, checked our grain and offered us a rate. We agreed. I was watching. Then the traders only made the bill,” she says.

Mostly single women visit mandis

“At some places, traders don’t even allow women to come inside the market,” added Vasavada. BehanBox asked the women who visited APMC mandi about their experiences.

Lassu’ experience, recounted at the start of this story, is telling of the difficulties women face in exercising their agency. About 10% of the farmers who visit the Bechraji mandi are women but they are mostly single women, according to Geeta Ben.

Of the 55 women we interviewed, eight were single women. Of these, only one visited the mandi. A young woman said her mother-in-law (a single woman) would go to the mandi but only to purchase seeds, not sell produce. Even those who come to the APMC mandi strategise their visits — they either come with their husbands or male relatives and if they are single, choose a quiet time of the day.

“Ekal mahilayein dopahar ke baad aati hain jab purush kam hote hain (Single women come after lunch when there are fewer men in the market),” says Mukta Ben, a Mahila Kisan Sakhi with WGWLO.

None of the women who came to the Bavla APMC mandi on the day BehanBox visited, had come to sell their produce. One woman was accompanying her husband to buy groceries, an elderly woman had just come to buy groceries and another had come with her husband and two children to get an Aadhar card made.

Facilities for women at the mandi were either absent or poorly maintained.

“There is no toilet for women in Patdi APMC,” says Lila. Basanti Ben from Patdi and Lassu Ben from Radhanpur too pointed this out about their local mandi. At the Patdi Mandi, the junior engineer told us that the mandi did have a toilet for women but it was broken.

Gauri Ben from Hassananagar village is not sure if Bavla mandi had a toilet exclusively for women. “What if there is a man inside?” she asks. Gohil, the mandi’s secretary, says that the mandi had a toilet for women but it was much smaller than the one for men.“Mahilaon ke liye toilet hain, purushon ke liye washroom hai (There is a toilet for women and a washroom for men),” he clarifies.

Women farmers set to lose more with changes in APMC regime

Despite the social barriers to accessing the mandi, almost all women we met knew the ‘teka bhav’ or the Minimum Support Price (MSP) for their produce. But the bargaining power that women have with the price signals through the APMC system will be compromised with the changed laws.

The premise that all farmers have equal access to internet and transport facilities and are ‘free’ to choose where and who to sell is flawed, we found. Women farmers, especially, have limited mobility and would have benefited from proximal markets with an oversight to protect them, highlighted MAKAAM in its statement on the new farm laws.

The example of Geeta Ben Rabari suggests that having more active women traders could also help. Exposure, familiarity and ease of use play a big role in furthering women’s agency. But with the new farm laws, bigger players not known to the farmers will come into the agricultural trade, discouraging women.

There is a long way to go when it comes to women’s active, meaningful, and effective participation in agriculture, showed the survey and the discussions with women, academics and activists. Customary practices are restrictive, as we said. And agricultural policies are not doing enough to encourage women to visit APMC mandis.

This reportage is part of the WGWLO and BehanBox fellowship on ‘Women’s land, forest and farming rights in Gujarat’

This story is edited by Malini Nair

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.