Krishnaveni’s Story And The Era Of Women Panchayat Presidents

- Bhanupriya Rao

P Krishnaveni remembers the night of 13 June, 2011, clear as day. Barely 200 m from her home of 15 years, in front of a local temple, she lay in a pool of her blood.

It was 10 pm, when her husband and two teenage daughters found her and screamed for help. No one came. When they finally lifted her into an auto-rickshaw, two fingers–one each hacked from her left and right hands–dropped to the floor. Her right ear was also severed.

The trauma of that day lives with Krishnaveni, but it made her more determined than ever.

“I don’t know how I am alive after that attack,” Krishnaveni, 42, told IndiaSpend. “It is a miracle. Maybe because I am a very adamant and courageous person.”

Thin and ramrod-erect, Krishnaveni, a Dalit, is known for her steeliness and confidence in her home village here at India’s southern end.

As president of Thalaiyuthiu panchayat between 2006 and 2011, Krishnaveni–once called “troublesome”–challenged and overcame caste prejudice, and fought a culture of patriarchy and a cement company that wanted village land. She confiscated commons that had been encroached by higher castes and tried to build toilets for village women on that land; she sat on the president’s chair in the panchayat office when her colleagues expected her–as a Dalit–not to; and to protest the discrimination she faced, unfurled a black flag instead of the tricolour on Independence Day, 2007.

Krishnaveni’s story is particularly striking, but there are many women who have emerged from the shadow of men and are carving a singular path as local leaders.

60% of women panchayat leaders now work independently, our study reveals

Krishnaveni is one of 40 past and current women panchayat, or village council, leaders who are the focus of an ongoing IndiaSpend study in six Tamil Nadu districts–Sivagangai and Tirunelveli in the south, Dindigul in the centre, Nagapattinam in the east, and Krishnagiri and Dharmapuri in the northwest of the state–analysing how the decisions made by female village leaders might be different from men.

After personal interviews over 1.5 months, and an analysis of the accounts of 43 panchayats of Devakottai block on Sivagangai district, this is what we found:

- Nearly 60% of women panchayat leaders (19 of 32) functioned independently, without male interference or support. These women had at their fingertips knowledge of panchayat accounts and government programmes executed through panchayats. Two were not allowed to function independently, but they were familiar with the accounts and programmes.

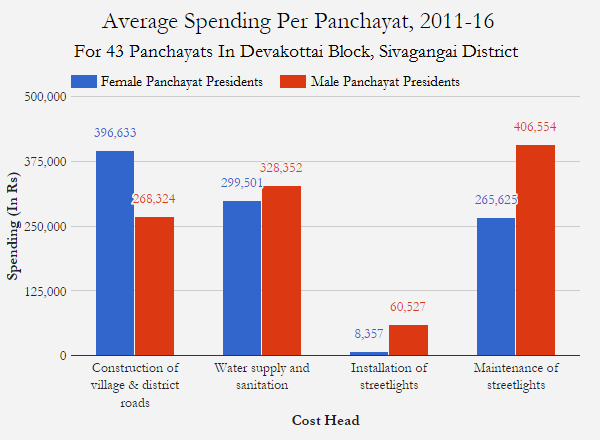

- Women panchayat leaders in Tamil Nadu invest 48% more money than male counterparts in building roads and improving access.

- In water-scarce Sivagangai, although male and female leaders spend equal amounts on water infrastructure, such as borewells and pipelines, women leaders invested more money in sophisticated water systems to ensure pure water for their constituents.

- While women tend to spend more on improving infrastructure, men tend to invest more (1.5 times) in regular maintenance, such as repair of water and street lights (men spent up to six times more on installing lights).

Tamil Nadu now has India’s lowest fertility rate–lower than Australia, Finland and Belgium–second best infant mortality and maternal mortality rate, and records among the lowest crime rates against women and children, as IndiaSpend reported in December 2016, but caste discrimination is entrenched and women in rural public office still face resistance from men. But the rise of women panchayat leaders indicates the benefits that reservation for women bring.

A quarter century of reservations, and women start making a difference

In 1992, India enacted the 73rd and 74th Amendments to its Constitution, reserving a third of seats for women in rural and urban local bodies to ensure greater representation for women in general and other excluded groups in particular, such as scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. Some states, such as Bihar, Himachal Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and–from this year on–Tamil Nadu and Gujarat, have extended the reservation of seats for women to 50%.

A quarter century after these constitutional amendments, women panchayat leaders, as we found, have made big leaps in transforming governance and making it more gender responsive, while negotiating patriarchy and caste. In doing so, they are becoming politically conscious and gaining identities distinct from men in their families.

Despite male resistance, women panchayat members had racked up a list of achievements in Haryana, IndiaSpend reported in January 2016, including building houses for the poor, installing water pumps and campaigning against female foeticide.

We found women in Tamil Nadu focussed on issues of immediate concern. In Kalaiyarkovil block of Sivagangai district, where the water is salty, five of seven panchayats running reverse osmosis (RO) purification systems were headed by women, according to data we obtained from the block development office (BDO).

In the forested, hilly panchayats of Krishnagiri and Dharmapuri districts, where child marriage is widespread, in six of seven panchayats we surveyed, women panchayat leaders were running campaigns against child marriage. Four of seven women panchayat leaders here were investing money in upgrading schools to higher secondary to curb dropout rates of girls, one of the main causes for early marriage.

Outcomes such as these are becoming more evident, but that does not diminish the struggles that women panchayat leaders undergo, as Krishnaveni did.

‘They would call me Ei Sakkilichi! Never by my name’

In 2006, Krishnaveni was 33 when she was elected the first Dalit–from a group called the Sakkiliars–woman president of Thalaiyuthu Panchayat. As president, one of the first things she did was to confiscate illegally occupied poromboke (commons) land and file cases against those who refused to vacate. They included Pallars, Muslims, Nadars, Thevars and Konars, all higher up the caste hierarchy.

Casteist slurs were regularly thrown at her by both Thevars and Pallars, themselves scheduled castes. “Pallars would call me, ‘Ei sakkilichi’ (you Sakkiliar woman),’ never by my name,” said Krishnaveni. “They used to threaten to thrash me. They are scheduled castes themselves, but feel superior to us Sakkiliars.”

Caste fault-lines run deep in Tirunelveli district. In 2015 alone, local activists alleged there were about 100 caste-driven murders in Tirunelveli and the neighbouring district, the Indian Express reported in April 2015. Many do not appear to make it to national records. There were no more than 52 caste-driven murders statewide, according to 2015 data from the National Crime Records Bureau.

While taking on male elites in the 10 villages under her jurisdiction, Krishnaveni, in 2006, opened another front against an equally if not more powerful force: India Cements, a cement company. She issued four pollution notices to the company, which has been running its flagship cement factory in Sankarnagar, Thalaiyuthu, since 1949.

But it was her campaign against a proposed captive thermal power plant by India Cements that brought her in direct confrontation with the company. As per Section 160 of the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Act, 1996, the permission of the gram panchayat is required before any industry is cleared within its jurisdiction. Krishnaveni refused permission for the power plant fearing further pollution.

The construction began anyway in 2011. “Through an RTI (right-to-information) request, I came to know that they had bypassed the panchayat and got permission from the district collector,” she said.

In early 2011, she filed a case against India Cements in the Madras High Court.

It was at this time Krishnaveni was zeroing on land for a community toilet. Toilets were a major demand made of the panchayat. Young and pregnant women defecated in open quarries at night, a time when local men would illuminate them with motorcycle lights.

Appeals to the district and state administration got her no money, so, as final recourse, she appealed to India Cements for money under their corporate social responsibility. The company agreed, if Krishnaveni’s panchayat would drop all cases.

“What could I do?” she said. “I received a lot of requests from little girls to build toilets. They specially came to the panchayat office to make this request. So I really wanted to do something for them. If as a woman I couldn’t understand this need, then who would? It was a difficult choice.”

In the end, she acquiesced, the deal being that she would drop the cases only midway through toilet construction.

The land identified for the toilets had been encroached by a ward member, who–along with another man whose land she had taken back–organised the attack on Krishnaveni, as she took an auto back home from the Collectorate, after discussing the toilet construction.

Suddenly, there were 15 men, armed with cricket bats and sickles.

“I thought they were going to attack the auto driver,” she said. “Next thing I know, they were hitting and hacking at me all over–on my head, my stomach, on my hands. And fearing I would run away, they hit me hard with the bat on my knees.”

They left her to die in front of the Karuppaswamy temple, near the library she had built for the village.

Dalit women, the power of the collector and the powerlessness of panchayats

Dalit women presidents face particular difficulties. One of the tools for harassment is Section 205 of the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Act, which allows the district collector to dismiss elected panchayat presidents.

Women appear to be disproportionately affected. In the five years to 2016, 42.5% of panchayat presidents dismissed were women, according to data we obtained from the directorate of panchayat and rural development; 30% of these were Dalit women.

There are other problems: Limited powers and money given to panchayats.

Tamil Nadu devolves 10% of state revenue as State Finance Commission Grants to panchayats.

But there are no devolved powers governing village-level institutions, such as health centres and schools, which are controlled by the respective state-government departments.

Most state grants are enough for only routine maintenance. An RO water system, for instance, costs upwards of Rs 600,000, or 60% of the annual budget for a panchayat with a population of 2,000 in remote, interior regions. Panchayats raise money through professional and house taxes, which are a fraction of those paid to urban local bodies.

To get schools and health centres upgraded, panchayat presidents must rely on persistent lobbying and political access to the Panchayat Union and District Union (additional tiers of local governance) or on members of legislative assembly or members of parliament. These are entrenched political networks that women, especially first-timers, find hard to access.

Many women leaders mentioned hours of lobbying with the district collectorate, sometimes over five years, without success.

The biggest disadvantage for a woman panchayat leader is the absence of a regular salary. Panchayat presidents only get a travel allowance of Rs 1,500 a month, most of which is used to reach regular meetings at the block and district level. Many spend their own money, but this is particularly difficult for women, since they do not, usually, control family finances.

Yet, the women do not back off.

A growing political consciousness: 30% will stand for re-election in 2017

Women panchayat leaders in Tamil Nadu, over the last 25 years, exhibit a growing political consciousness.

Even though the panchayat president is a non-party position, 43% women in the study belonged to a political party, mainly the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK). In 1996, Tamil Nadu was the first state to reserve a panchayat seat for women for 10 years instead of five, as other states do.

As many as 30% of the women we interviewed said they would stand for re-election in the upcoming panchayat elections in April 2017, even if they did not represent a seat reserved for women.

Back in Thalaiyuthu, Krishnaveni appeared to have gained acceptance across castes and communities.

When she lay in the hospital in Tirunelveli, Konar youth donated blood. The village folk said they appreciated her work and the acknowledged the harassment she faced. Her greatest support comes from women ward members.

“Earlier, I used to give her a tough time too, after listening to the Muslim men,” confessed Mohammeda, a Muslim ward member. “But when I realised that she was being harassed unnecessarily by the men, I started to support her.”

It’s been six years since her attack, many of her wounds have physically healed, although there are deep scars on her neck and hands. Her hair has grown back. But she still finds it difficult to sit for long periods with her legs folded.

Today, Krishnaveni lives among her very attackers, a couple of houses away. “I feel enraged everytime I see them,” she said. “Sometimes, I just want to go out and kill them all. I have gone through so much because of them.”

Krishnaveni stood for re-election in 2011 and lost. What, we asked her, really hinders women in politics?

“Anatthikam,” she said. Patriarchy.

This story was first published on Indiaspend on March 08, 2017.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.