Why Ashubi Khan’s Pioneering Run Ends Today

Ashubi Khan, 51, is distraught. A decade of trailblazing work done by this tall, soft-spoken sarpanch (village chief) and her team of seven illiterate women–and three literate men–ends today.

Over the decade, despite male resistance, which once led them to resign en masse in protest, the chief of Haryana’s first all-women panchayat in 2005, Khan, and her then nine women panchs (ward members) in southeastern Haryana’s Neemkheda gram panchayat (village council) racked up an impressive list of achievements.

The 10 women carried out a successful campaign against female foeticide. In a district with severe water shortages, they had 20 pumps installed and Neemkheda connected to a canal. They had 50 houses built for poor households. Their greatest achievement, according to locals: Upgrading the primary school to secondary level.

In 2008, the Haryana government declared Neemkhada and its illiterate, female gram panchayat a ‘model village’.

After building new roads and anganwadis (creches), Khan’s next-term plans were to get a much-needed public health centre to her village in Punhana block.

But tomorrow, as Mewat goes to the polls, Khan and her seven women panchs can no longer stand for elections, thanks to a much-criticised amendment to the Haryana Panchayat Raj Act, 1994. Thousands of women, dalits (backward caste) and general candidates across this northwestern state are now debarred from the panchayat elections, which began on January 10.

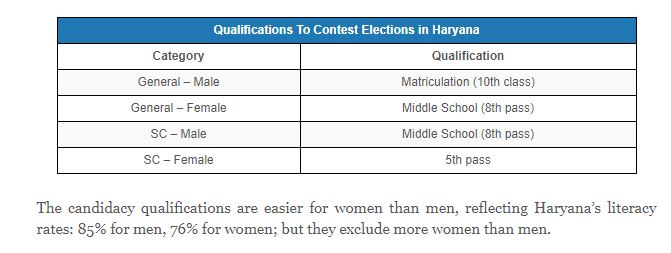

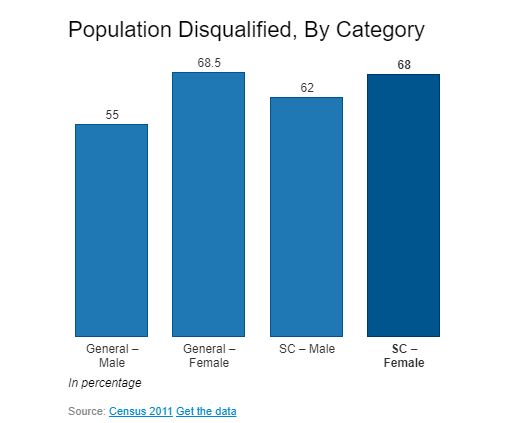

The new law–legislated by the Haryana Government and upheld by the Supreme Court of India–among other things, prescribes minimum educational qualifications for candidates, thus excluding more than half the rural population from candidacy.

The new panchayat law, and the citizens it excludes

A toilet at home. No pending loans to agricultural cooperatives. No unpaid electricity bills. Minimum educational qualifications.

These are some of the pre-conditions the Haryana government now imposes on electoral candidates, after amending the Haryana Panchayat Raj Act, 1994, on September 7, 2015.

On December 10, a two-member bench of the Supreme Court, hearing this writ petition, upheld the law, declaring the restrictions “reasonable”.

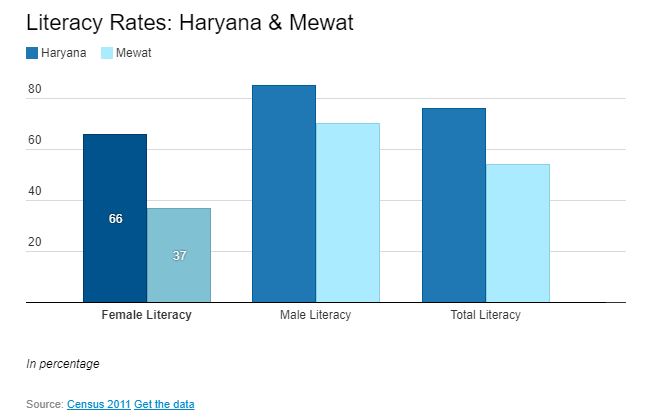

Mewat, with 54% literacy, is worst hit

Nowhere is Haryana’s electoral exclusion starker than in the Muslim-majority district of Mewat, about 100 km south of India’s capital, Delhi.

In 2008, the Centre classified Mewat–where 79% are Muslim– as one of 90 Minority Concentrated Districts that required special help.

The average literacy rate in Mewat, according to the 2011 census, was 22 percentage points lower than Haryana. The female literacy rate, at 37%, is amongst India’s worst for a district.

This means 89% of women and 80% of men (in the age-group 20 years and above) cannot contest elections in Mewat. Among scheduled castes, 64% men and 63% women are similarly debarred.

Not enough schools, but people without required education debarred

“Ab hum anpadh hain, toh isme hamri ke galti hai? Humre jamane mein toh sakool hi na tho, (Am I at fault if I am illiterate? In my time, there wasn’t a single school in my village),” an angry Ram Pyari, a dalit, and the most vocal member of the Neemkheda panchayat, told IndiaSpend.

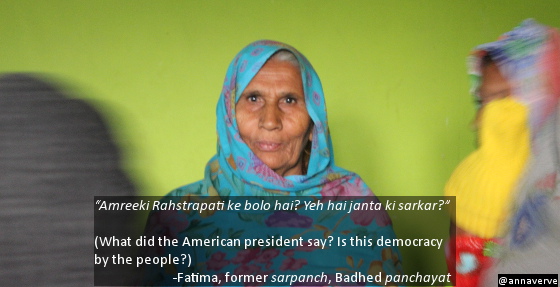

“Hamari majboori hai, hum kya karein? (We are helpless. What are we supposed to do?),” said Fatima, a sentiment echoed by 50 other women of Badhed panchayat who gathered to express their anguish and concern at the new law.

“There was only one school earlier, which was beyond that hill,” said Fatima. “Only boys could go. Girls could not go that far to study. So we remained illiterate.”

Mewat does not have enough schools, particularly middle and secondary. While the number of middle schools doubled from 129 (2001) to 272 (2011), not all villages have middle schools, according to a recent NITI Aayog report.

There are fewer secondary schools in Mewat, 84, serving 3.2% villages, according to the 2001 census.

In 2014-15, that figure was 86–an increase of two schools in more than a decade—according to the District Information System of Education (DISE), a national school- statistics database.

Between 2001 and 2011, the number of senior secondary schools rose from 65 to 70: an addition of five.

Since there aren’t enough schools and religion plays a big role in educational decisions, girls in Mewat are mostly sent to madrasaas, which means they are not counted as literate. Mewat has 77 madrasaas, according to a 2009 study by the Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR).

Poor and marginalised adversely hit by candidacy bans

Educational qualifications apart, the Haryana panchayat law disincetivises the poor and marginalised from contesting elections in myriad other ways.

Candidates contesting elections have to–in their election affidavit–attach a picture of a functional toilet, clearances from three agricultural co-operative banks, clearances of electricity dues, and a clearance from any criminal charges from their local police stations.

In a district where only 17.8% of rural households have access to a functioning toilet, this immediately excludes about eight of 10 otherwise eligible people from contesting.

To get loan-clearance certificates is also difficult. Candidates must pay Rs 200 for each clearance–from three banks at varying locations–and Rs 28 for a ‘no-dues’ certificate from the electricity board.

Locals said they spend between Rs 4,000 and Rs 6,000 for these clearances, which take time away from regular jobs and domestic responsibilities. Panchayat ward members get a stipend to help discharge public duties: Rs 400 a month.

Unintended consequences: A rise in polygamy

In village after village in Mewat, IndiaSpend found it was nearly impossible to find candidates with the educational qualifications to contest elections. In many gram panchayats, the electoral process is over before it started. Candidates are elected unopposed or seats are vacant.

In Punhana block, data from the State Election Commission reveal, five of 66 sarpanch posts went unopposed. Of 788 ward-member posts, 508, or 64%, were elected unopposed. In 2010no sarpanch position was won unopposed. Only 271 ward members were elected unopposed.

As many as 61 of 788 wards, or 7.75%–most reserved for women–have no candidates. Elections will be held only for 61 sarpanch posts and 158 ward posts.

In panchayats where single candidates filed nominations, they came from elsewhere to contest elections, with no stake in village governance.

In Neemkheda, with the outgoing sarpanch Ashubi Khan now unfit to contest, her nephew Wasim, from a village in Ferozepur Zirkha Block, 30 km away, has been persuaded to interrupt his medical education and contest.

At the ward level, a lone woman candidate from outside the village has filed her nomination–from all the four wards in Neemkheda, three of which she must eventually vacate.

In neighbouring Badhed, the ward posts will stay vacant. The former sarpanch, Fatima (50), explains how her first term as sarpanch in 2005 transformed her. She learnt to navigate the power structures within the village and built some agriculture infrastructure. Fatima (she uses only one name) is illiterate, so she cannot–as she hoped, continue her work and deliver much-needed drinking water and public-health services to her panchayat.

In Jamalgarh, one of the bigger gram panchayats, with 20 wards, nine candidates were elected unopposed. Nine seats will lie vacant, and two seats will see a contest.

In Bandholi gram panchayat of Punhana block, of the seven wards, three have no contestants and will stay vacant.

Posters of candidates in gram panchayats in Palwal district now mention shikshit (educated) as one of the achievements of the candidates.

Mewat is also witnessing a rise in polygamy among the largely Muslim Meo community, with men taking second wives–with the educational qualifications needed to contest elections.

In Jamalgarh, two men–one of them middle-aged–married again. In Singaara gram panchayat, the outgoing sarpanch, Hanif, married Sajida, 14 years younger and eligible to contest the elections.

Deen Mohammad (47) of Aklimpur-Nuh married Sajida (23), an eighth-class pass.

“Agar jeet gayi toh theek hai. Agar haar gayi toh kya hoga? Kahan jayengi? Unka toh talaaq ho jayega. Yeh, auraton ke saath bohot zyatti hai. Is kanoon se is cheez ko badhawa mil raha hai (It is alright if she wins. What will happen if she loses? She will be divorced and abandoned by the man. This law is very unjust to women),” said a worried Subhan Khan, outgoing sarpanch of Badhed.

Haryana electoral exclusion mirrors Rajasthan‘s. That state enacted similar laws in March 2015. In elections held soon after, the number of sarpanchs elected unopposed increased from 35 in 2010 to 260 in 2015; that’s 2.6% of sarpanch posts, data from the State Election Commission reveal.

As many as 43% panchayat ward members were elected unopposed and 542 seats (0.5%) remained vacant in Rajasthan.

How the law reverses the aims of panchayati raj

The Supreme Court, while upholding the Haryana Amendment Act, noted that it is not “irrational or illegal or unconnected” to impose minimum educational qualifications as “this would enable the candidates to effectively discharge duties of the panchayat”.

The 73rd Amendment of the Constitution aimed at empowering grassroots democracythrough local government, or panchayati raj institutions.

Ashubi Khan and other women panchayat members vehemently disagree with the Supreme Court.

“We have run panchayat much more effectively over the last 10 years despite being illiterate. We have done what even an educated man could never to,” said Ashubi Khan.

It is ironical that panchayat leaders who have been at the forefront of improving school infrastructure should be debarred from contesting elections for lack of education.

Locals in Neemkheda and Badhed panchayats are aware of the beneficial effects of education, but as one said: “This should not be a barrier to contesting elections.”

MPs/MLAs can be illiterate, criminal but not village representatives

A sarpanch in village India is more than just an elected representative. Those occupying these positions are, often, bearers of local common and cultural knowledge and experience and are closely connected with their constituents.

The Supreme Court, in its judgment, said that it agreed with Attorney-General Mukul Rohatgi’s submissions during the hearings that the law was meant to elect “model representatives for local self government for better administrative efficiency”.

“How is education relevant to understand what the community needs–where a road needs to be built to solve drinking water needs?” asked Subhan Khan, the outgoing sarpanch of Badhed panchayat. “Those debating and making economic and foreign policy at the national level are not demanded of this, why for us?”

While pronouncing the judgment, the Supreme Court admitted this was creating “two classes of voters,” that is, “those who are qualified by virtue of their educational accomplishment to contest the elections to the panchayats and those who are not”.

The judgement also creates two classes of elected public representatives with different rules and privileges: Members of Parliament (MP) and Members of Legislative assemblies (MLAs); and members of local village councils and urban bodies.

Here are some disparities:

* MPs and MLAs need not have minimum educational qualifications but panchayat members do.

* MPs and MLAs can declare liabilities (loans) in their election affidavits but panchayatmembers need to attach loan-clearance certificates as part of their affidavits. The top 10 MLAs, according to 2014 election affidavits, have reported liabilities ranging from Rs 43 crore to Rs 3 crore in the Haryana Assembly.

* MPs and MLAs can default on payment to public utilities like telecom company Mahanagar Telephone Nigam (MTNL), but panchayat leaders need to attach clearance certificates of electricity dues.

* MPs and MLAs can contest elections despite criminal charges–they only need to declare them in their affidavits–but panchayat leaders need to append certificates from their local police stations clearing them of criminal charges.

“What is the education of Chief Minister ML Khattar?,” asked Ram Payari of Neemkheda.

Chief Minister Khattar is a graduate, but some of those who legislated this exclusionary law do not have the same qualifications they now demand of their panchayat colleagues. Of 90 MLAs in the Haryana assembly, as many as four MLAs are eight-standard pass, and one is an illiterate.

In Mewat, Lincoln is quoted: ‘This democracy is not by the people

“What did the American president say? Is this democracy by the people?,” said Fatima, referring to Abraham Lincoln’s famous words about democracy.

Another member added: ‘Janta ki shaasan khatam ho gaya hai. Ab Sarkaar ka shaasan hai(The rule of the people is over. This is a rule by the government).”

This story was first published on Indiaspend on January 16, 2016.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.