Women May Own Land In Gujarat But Men Control It

- Aarefa Johari

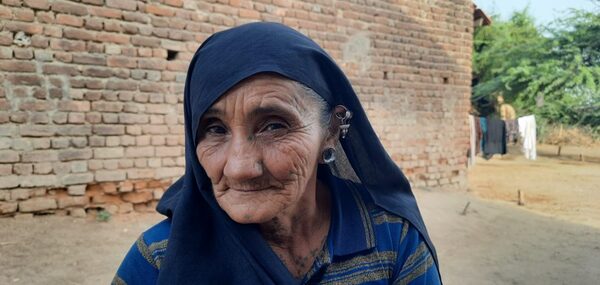

Shankuben Rabari insists she is 40 years old.

She has grey hair, a deeply wrinkled face and arms dotted with the green tattoos distinctive to elderly women in her community. Shankuben snaps at anyone who suggests she must be at least 60.

“I look older only because my teeth fell out,” she said, as younger women from the neighbourhood suppressed their laughter. “And because I work hard on the farm all day.”

Shankuben may be mistaken about her age, but she is not wrong about her workload.

Shankuben’s family comprises her, her husband Ramabhai, his aged parents and her two sons. They own six cows and cultivate five bighas – roughly two acres – of land in Vadnagar, a village in Gujarat’s Patan district. It is a portion of the ancestral land that her husband’s grandfather used to own.

In the Maldhari or pastoral community to which they belong, the man takes the family’s cattle out for grazing. The woman does almost everything else.

“My husband is out with the cows all day. My sons have milk delivery jobs. And I do all the housework and farm work,” she said.

In recent years, Shankuben has become keenly aware of how disproportionate this division of responsibilities is. “I milk the cows and manage the sales to the dairy. I manage our budget. I go to buy seeds and fertilisers. The men help, but I do the sowing and the watering and harvesting. So it makes sense that our khetar [farm] should belong to me, doesn’t it?”

Now, Shankuben is on the verge of becoming one of the first Maldhari women in Vadnagar to get equal and joint ownership over her marital property while her husband is still alive, instead of merely inheriting it as a widow.

This phenomenon is so unusual in Gujarat, it has a name of its own: hayaati ma haq, or rights during [the husband’s] lifetime.

Shankuben’s journey towards asserting her rights and getting hayaati ma haq began in 2017, when her husband, Ramabhai Rabari, discovered that the inheritance of his land was just oral and informal. His grandfather’s death in the 1980s had never been officially reported to the state’s land revenue department. In government records, therefore, Ramabhai’s land was still in his grandfather’s name, undivided from the land he thought had been bequeathed to his brother and cousins.

The family did not know how to correct the land records, and the lawyers they approached were unaffordable.

In 2019, Shankuben happened to mention her family’s land dilemma at a village-level women’s meeting organised by MARAG, or the Maldhari Rural Action Group, a non-profit organisation that works for pastoral communities in Gujarat.

The social workers from MARAG did more than just help the Rabaris apply for a change in land title records. They also made Shankuben aware of the value of her labour, and her moral rights over the land she tills. Over the next few months, they convinced Ramabhai to add her name as the joint title-holder in his application to the land revenue department.

The Rabaris’ application has been pending for the past 20 months, and Shankuben cannot wait for it to be approved.

“Women work more than men, so we should get rights over land too,” she said. “My husband also understands this and supports me.”

When Ramabhai returned from the day’s grazing, however, he voiced a different view. “The social workers had explained that we can get some government benefits if a wife’s name is added to the land,” he said. “If there were no benefits, I would not have put her name in the application.”

This contradiction is revealing of the broader tensions over the idea of women’s land ownership in Gujarat. For most rural women, land ownership is linked to ideas of empowerment, identity and personal security. For most men in their families, allowing women land ownership is culturally alien, and is considered seriously only when there are benefits to be gained in cash or kind.

This has meant that even when women do get ownership over land, it is often meant to serve the needs of men, who retain control over it.

India does not collect any gender-disaggregated data on land ownership, but the agricultural census comes close: it provides gender-wise data on operational land holdings, a term that reflects who manages and makes decisions about operating agricultural land, irrespective of legal ownership.

The last census, of 2015-’16, found that women operate just 13.9% of India’s operational land holdings – a marginal increase from the 12.8% recorded in the 2010-’11 agricultural census.

Gujarat fared slightly better than the national average. Even though the population census of 2011 found that 78.6% of rural women in Gujarat were engaged in agricultural work, the agricultural census of 2010-’11 found that just 14.1% of women were operators of land holdings in the state. In 2015-’16, this improved marginally to 16.4%.

As far as men are concerned, the reason for this lopsided land-ownership pattern can be summed up in one word: maryada. The word means dignity, but a deeply patriarchal society has twisted it in ways that became apparent to me during conversations with women in two villages in Surendranagar district.

I first went to the Dalit quarter in the village of Gavana, where women were relaxed as they talked about their lives, longings and the land they work on.

“Our family has a lot of land, 15 bighas, in my husband’s name,” said Manjulaben Parmar, 47, sitting with her legs stretched out on a cot in her three-room house. “This year, he is going to add my name to the land, along with my sons.” His reason for deciding to add her name to their land records was his belief that they would be able to access more government benefits as a family.

Just then, a tall, bearded man in his twenties entered the room, prompting Manjulaben to suddenly sit up straight. She introduced the man as her older son, just back from the day’s work on their farm.

“Yes, my father has decided to add mummy as an inheritor,” said the man. Wiping his sweat off with a gamchha, he added, “As such my mother has no right over my grandfather’s land. Our women usually get land only as widows. That’s just how it is – women have their maryada.”

As he left, 65-year-old Santaben Parmar, Manjulaben’s sister-in-law, pointed out that a wife does, in fact, have a right to her husband’s land.

“I work on the farm too, and I do the housework, which he [her husband] does not,” said Santaben. “I would like to have my name in the land, of course I would.”

Has she ever told her husband this?

Santaben’s eyes widened in shock, and she shook her head. “Em na karai, we cannot do that in our culture!”

Minutes later, Laduben Jhala had the same reaction. “We may feel bad about it, but it would not be accepted if we ask for a right in our husbands’ land,” said Laduben, 38, who had come to visit Manjulaben from down the street.

While the Parmars are Vankar Dalits, a community of weavers, Laduben is a Valmiki Dalit, traditional sweepers and manual scavengers considered the lowest in the caste order.

“Most Dalits don’t let Valmikis enter their homes, but I am more modern. In our house, we don’t follow this,” said Amarsinh Parmar, Manjulaben’s husband, who joined the conversation when he walked into the room and saw Laduben Jhala.

His presence prompted all the women to hurriedly pull down their sari pallus over their faces. When I asked them why they had done so, Amarsinh spoke first, explaining that this veiling was called “laaj kadhvanu” – maintaining shame or modesty.

“It is all part of women’s maryada,” Amarsinh said. “In front of other men, women generally maintain laaj, sit properly and talk softly.”

A short distance away, in the village of Jaravla, a group of Patidar women gathered to have similar discussions on land, rights and propriety for women.

“We Patels don’t practice laaj kadhvanu anymore, at least not in our village,” said Jayaben Patel, 63, whose sari covered her head, but not her face. “People of other castes still do it, but we have become more modern.”

The Patels, or Patidars, are a socially-dominant caste that has traditionally owned vast tracts of land in Gujarat. But as with the Dalits, even among Patidars, land is owned by the men.

Jayaben’s husband recently made her a joint owner of his 10 bighas of land, but only because he wanted to formally transfer land ownership to his sons in his lifetime. Under the Hindu Succession Act, a wife is a man’s first legal heir, and if he wants to bequeath inherited land to his children, he has to first make her a joint owner of the land.

“My daughter-in-law has not been added, not yet,” said Jayaben. “That is not the custom.”

Vasantiben and Kokilaben Patel, both in their 60s, nodded in agreement. “If you give land to a daughter-in-law, she might leave and not take care of us,” said Vasantiben, a widow with two daughters-in-law. Her daughters, who had initially been listed as inheritors of the family land, were removed after they were married.

“If you give land to a daughter, her husband and his family might take it,” said Kokilaben.

“Yes, women cannot be trusted either as dikris or vahus [daughters or daughters-in-law],” said Kokilaben’s 27-year-old daughter-in-law Neeru Patel, her voice dripping with sarcasm. “Only men can be trusted.”

Women’s access to land rights should not have been so abysmal. Certainly not after 2005, when the Hindu Succession Act was amended to grant daughters equal inheritance rights over family property.

Despite this amendment, daughters and sisters are conspicuously missing from land records. According to a 2014 study in nine states, nearly half of women land owners received ownership rights only as widows’ inheritance, after their husbands died.

Perhaps the most common and least surprising excuse is that a daughter does not “belong” with her parents. Since she is to be married and sent away, her name is often omitted from the family’s pedhinama – an official document listing a property owner’s legal heirs. Pedhinamas are a mandatory part of land ownership documents in Gujarat, and the village talati, or revenue officer, is responsible for ensuring that the document is accurate and updated every few years.

Even when a daughter is listed in the family pedhinama, she is often expected to surrender all claims to her share in her father’s land, usually soon after she is married. Once she signs a formal declaration about willingly giving up her claim, her name is struck off the pedhinama.

A 2014 study in 34 Gujarat villages found that 22.2% of the surveyed women had to give up their claims over agricultural land over the preceding three years. According to the Working Group for Women and Land Ownership, the non-profit organisation which conducted the study, most of the women had been forced to give up their claims.

In many Gujarat villages, however, women describe surrendering their claims as a normal, natural thing to do.

“When I got married years ago and moved to a different village, I gave up my haq over my father’s land,” said 44-year-old Shankuben Chaudhary from Patan district’s Arjansar village (not to be confused with Shankuben Rabari from neighbouring Vadnagar). “In 2015, my husband’s sister also gave up her haq in my in-laws’ land. She said she was married and did not have a claim here anymore. Most women do this.”

Chaudhary’s neighbour, Jashiben Chaudhary, explained why. “It is not acceptable for a woman to keep her claim in her father’s land after marriage,” she said. “After all, her children receive mameru from her brothers.”

Mameru is a wedding custom in which a bride receives money or jewellery from her mama, or maternal uncle. The amount of mameru given varies from family to family. The ritual is so significant across Gujarat’s caste groups that the state government has a scheme offering Rs 10,000 as mameru for adult brides from Scheduled Caste families.

Although a mameru does not directly benefit the mother of a bride (and does not benefit her sons), it is implicitly perceived as a compensation for the land rights she often gives up when she leaves her father’s home.

Shankuben Chaudhary claimed that there was another practical reason for women to give up claims on their father’s property. “It is difficult for a married woman to keep travelling to her father or brother’s home to sign on farm loan applications and other documents,” she said, echoing many other men and women I met in Gujarat’s villages. “All joint landowners need to sign on such documents.”

This, of course, is not seen as a problem when male landowners migrate to cities for work and leave their farms with other men in the family. In fact, a government official pointed out that a joint owner’s absence should not be a problem at all. “If there are multiple people listed as joint owners of a plot, one person can be appointed as an authorised signatory for loans and other applications,” said MR Parmar, the deputy director of agriculture in the state government.

In Surendranagar district’s Fatehpur village, 45-year-old Madhiben Thakor is one of the rare women benefiting from this.

When her mother died nearly 40 years ago, Madhiben’s father refused to remarry despite the advice of his relatives. “He raised me and my brother by himself, and he was very attached to both of us,” said Thakor. “When he died, he left 20 bighas of land for each of us.”

When Thakor got married, she authorised her brother to operate her land. “My brother grows jowar and bajra and cotton on it, and sends the income from the harvest to my bank account,” said Thakor, who earns around Rs 10,000 per season from her farm. “It is nice to have my own income, because my name is not included in my in-laws’ land.”

The refusal to include a daughter-in-law as a vaarasdar, or heir, in a family’s property is widespread across Gujarat.

In Vadnagar village, for instance, Hirabhai Chaudhary split his 30-bigha farm into three portions in 2019, transferring two nine-bigha plots to his sons, and keeping a 12-bigha plot for himself. One of his sons has been married for over three years, but Hirabhai has not yet made his daughter-in-law a joint title holder along with her husband.

“She is still new to the family,” said Hirabhai, “Maybe we can add her after she has her first child.”

Hirabhai’s wife, 48-year-old Dhudiben Chaudhary, has spent three decades of her life as a daughter-in-law, raising two sons and three daughters into adulthood.

But it was not until Hirabhai split his land in 2019 that her name was finally added to the family pedhinama and to his 12-bigha land title. Unsurprisingly, this decision was motivated by the lure of potential government benefits to Hirabhai.

Farmers and even social workers often hold misconceptions that the Gujarat state government offers benefits to women farmers, through initiatives such as the seven-year-old i-Khedut, under which landowners can apply for the purchase of subsidised farm equipment. But MR Parmar, a deputy director of agriculture in the Gujarat government, pointed out that i-Khedut does not prioritise women farmers, and does not offer any special subsidies for women. “State-sponsored subsidy schemes offer 50% subsidies to all farmers,” said Parmar.

But, he added, benefits are available to women farmers through central government schemes. “There are some central government schemes that offer 40% subsidies to farmers in the general category, and 50% to women, Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe farmers,” he said.

Parmar was referring to the union agriculture ministry’s Sub-Mission for Agricultural Mechanisation, which offers 40% subsidies on tractors, power tillers, and other equipment for general category farmers, and 50% for women farmers. The Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture also has sub-schemes that offer a variety of agricultural equipment at lower costs to women farmers.

In Gujarat, grassroots social workers advocating for women’s land rights are not familiar with the names or features of these specific schemes, but often refer to “sarkari labh” or government benefits as a strategy while talking to male farmers.

“In our meetings with women, we tell them that they have equal rights over the land they till, but men do not accept this point so easily,” said Sooraj Desai, a social worker with MARAG in Patan’s Radhanpur block. “Most of them are willing to add women’s names to their land only when we tell them there are government benefits.”

To follow through on her claims, Desai stays in touch with block-level officials for updates on any available subsidies or schemes that could benefit women landowners. “These schemes and offers are not available all the time for every village, so whenever they are open, I inform farmers and help them fill forms for the women,” said Desai.

In some rural families, women’s names are added to land titles not for the sake of government benefits, but because men cannot legally buy land in their own names.

One reason for this is the land ceiling law, an integral part of India’s post-Independence land reforms. Gujarat’s Land Ceiling Act of 1960 sets a maximum land ownership limit of 54 acres per owner (or group of joint owners), with some variations in different regions, so that surplus land is acquired from large landholders and redistributed among the landless.

“My son-in-law recently bought 10 bighas [around 4 acres] of land in my daughter’s name,” said 63-year-old Jayaben Patel from Jaravla village in Surendranagar district. “He could not buy it in his own name because of toch maryada [land ceiling] rules. He already owns more than 50 acres.”

According to Jayaben, her son-in-law’s decision prompted her own husband, Amrutbhai Patel, to add her name to the title deed of their 12-bigha plot.

Amrutbhai, however, had a different story. “I added my wife to the title because I wanted to officially make my sons varasdars. And legally my wife is the first heir, before my sons,” he said. “As such it does not make a difference whether a wife is added or not. She is not going anywhere anyway.”

Another law that has inadvertently given women more access to land ownership is the Gujarat Tenancy and Agricultural Lands Act, which was amended in 1973 to prohibit non-farmers from purchasing agricultural land.

The purpose behind this amendment was to prevent industrialists and other moneyed non-agriculturalists from buying up farmland indiscriminately, without seeking specific approvals from the government. But this law has also posed a problem for tenant farmers who do not have land titles of their own and lease other people’s farms for short periods of time.

“By law, tenant farmers should be recognised as farmers, but this does not always happen on the ground,” said Gova Rathod, convener of the non-profit Jamin Adhikar Jumbesh, a land rights organisation in Gujarat.

In Patan’s Vadnagar village, Amarben Rabari’s husband is one such tenant farmer.

“My husband’s entire family has been farming on leased land for years, and none of them are recognised as farmers,” said Amarben, 60. “But I am a varasdar in my father’s property, so I am a farmer and I can buy khetar ni jameen [agricultural land] under the law.”

Taking advantage of his wife’s farmer status, Amarben’s husband saved up for years and finally bought 10 bighas of farm land in 2019. At the time, the purchase was informal and Amarben’s husband paid over Rs 20 lakh without initiating paperwork. “Now, we have applied to get the land registered in my name,” she said.

If male family members did not have ulterior motives for adding women to land titles, how many women in Gujarat would actually own land?

Women’s rights activists do not have a clear answer, but they fear they would face an even harder time working to improve the rates of women’s land ownership. The government and its representatives, they say, are simply not doing anything.

At the village level, for instance, a revenue officer, or talati, is the one responsible for verifying each family’s land documents and ensuring that no eligible legal heirs – particularly women – are left out of a pedhinama.

“But talatis are not doing this work properly,” said Nafisa Barot, the co-founder of Utthan, a non-profit organisation working on rural development in Gujarat. “In fact, many talatis let families hide women’s names or actively discourage women from demanding their land rights.”

At the state level, the government has done close to nothing to actively promote or incentivise women’s land ownership. In 2006, the state government did introduce Nari Gaurav Niti, a policy that aimed to promote gender equality in the state in education, health, and skill development, among other fields. It included an initiative to encourage the registration of land under women’s names through the exemption of stamp duties and registration fees. “But there is no clear data on how effective this policy was or what its current status is,” said Itishree Pattnaik, assistant professor of economics at the Gujarat Institute of Development Research in Ahmedabad.

When she sought data in 2014, government officials told Pattnaik that 30% of the total documentation of land and property in Gujarat had been done solely in women’s names in the three years after Nari Gaurav Niti was introduced. “But I found this very unlikely. I had done a field survey of 400 households in four districts in 2014, and I found just 3% land ownership in the names of women.”

There is little information available in the public domain about the current status of Nari Gaurav Niti in Gujarat. In 2014, the Times of India reported that the policy had “fallen into neglect after initial enthusiasm”, but that then Chief Minister Anandiben Patel planned to “refashion and implement it for greater gender equality”. But the women and child development department’s website has no information on the policy and officials from the department did not respond to email queries about it.

Pattnaik believes policies such as Nari Gaurav Niti are unlikely to work well because they are “half-hearted”, framed and implemented by men who have little understanding of women’s real needs and problems. “I don’t see any future of these policies until we change mindsets. For this, we need widespread education, which will take a long time to yield results,” said Pattnaik, who believes the idea of women’s rights to land should be introduced in school textbooks. “For this, we need larger-level, institutional support from the state.”

In the absence of such institutionalised efforts to bring about change, land rights activists and women farmers in Gujarat draw hope from the few families who embraced women’s empowerment for its own sake.

One such family is that of Lilaben Rabari in Patan’s Arjansar village.

In 2019, when Lilaben’s father-in-law transferred 20 bighas of ancestral land to her husband Pachanbhai’s name, she publicly voiced her desire to have her name added to the land title.

“I was at a meeting on women’s rights in the village, and I told them that I would like my name in the land,” said Lilaben, 42, who had been keenly attending MARAG meetings for five years. “My husband was at the same meeting, and he immediately agreed.”

“It is true that my wife does more work at home and on the farm,” said Pachanbhai. “Her name should be on the land too.”

The couple has now split their land into three plots on paper – one each for Pachanbhai, Lilaben and their 23-year-old son – but continue to farm on the whole plot together as they have done for years. Lilaben is aware of how different her husband is from other men in her community, and has ensured that her son, Ramesh, also shares the same views.

“I believe in gender equality and women’s rights,” said Ramesh, a computer science student. “If I get married, I will add my wife’s name in the land title too.”

[This story is produced as part of the WGWLO-BehanBox reporting fellowship on women’s land, forest and farming rights in Gujarat.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.