‘The Money Is Little But The Respect ASHA Workers Get Makes Me Happy’

An ASHA worker from Assam talks about the pandemic years, support from family, and the trials of being a caregiver for her family and community

This interview is part of The ASHA Story, the first public archive of women workers’ lives and histories. Read the other stories here.

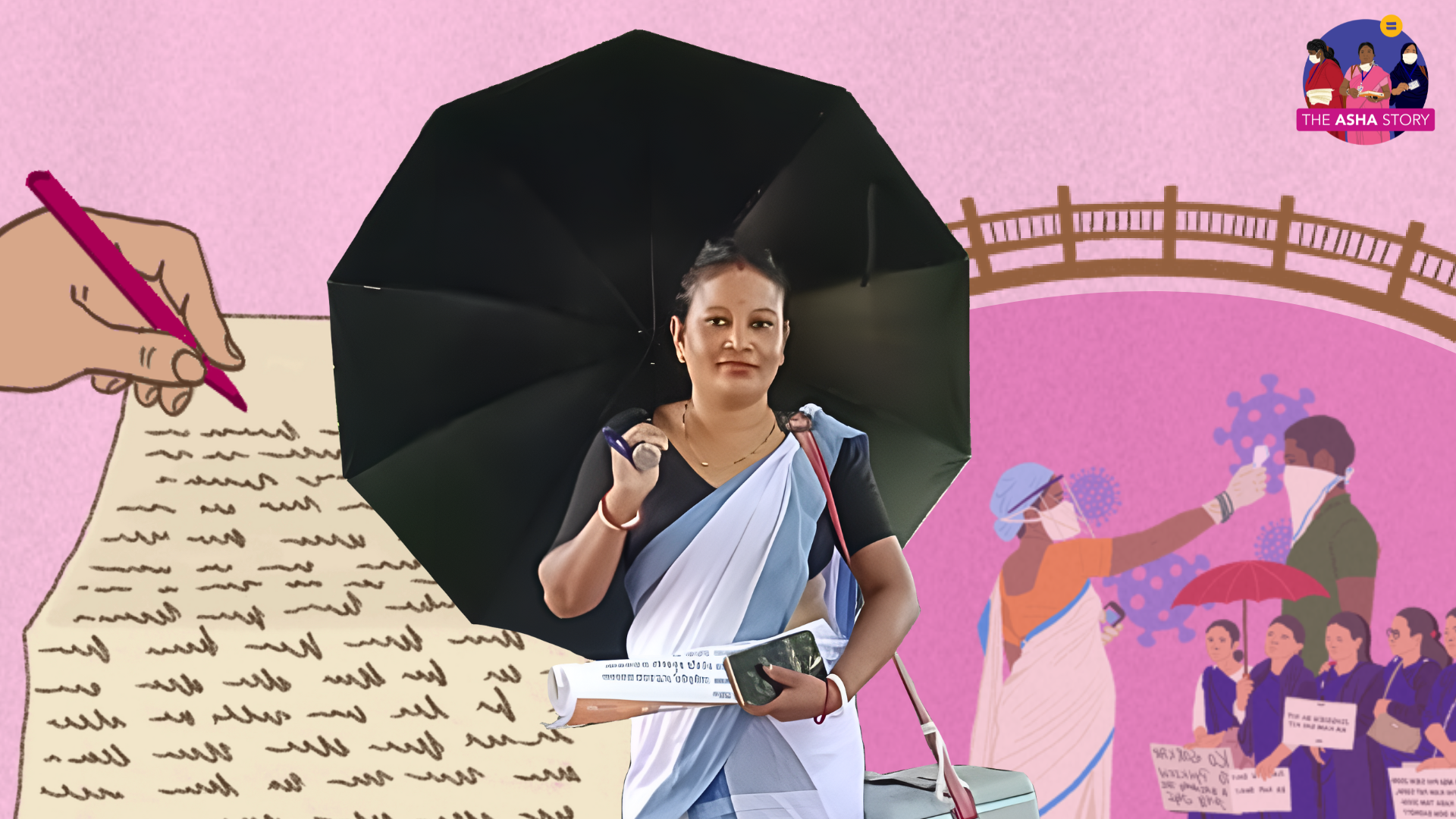

Pratima Barman, 37, lives in a remote riverine village in one of the most inaccessible corners of Assam. As an ASHA worker, she negotiates floods, long journeys, and rebukes from both officials and patients, while supporting a large family – of her five children, the oldest is doing a Bachelor’s degree while the youngest is in primary school. The job pays peanuts, and some days are incredibly tough, but it has given her something invaluable: respect.

In a conversation with Tora Agarwala, Pratima speaks about the early years, the support that made her work possible, cycling her way through villages, and the pandemic years that created new challenges. The trials of being a caregiver for her family and community take a toll, but she says with a calm resignation: “We get hurt, but we also learn to forget.” Edited excerpts below:

How did you become an ASHA worker?

I live in the middle of the Brahmaputra in Mechaki Chapori [‘chapori’ in Assamese means a low-lying riverbank village, thousands of which dot the state]. The only way to reach our village–located in Dhemaji district–is by boat, and Dibrugarh, the nearest big town with a proper hospital, is about six to seven hours away.

In 2005, Boat Clinics came to our village. These were special boats run by the non-profit Centre for North East Studies (C-NES) in partnership with the National Health Mission (NHM) that provided free healthcare to remote riverine villages in Assam. Once a month, doctors and nurses would arrive by boat, set up a tent, and conduct medical check-ups. We would await the boat clinics eagerly: in our village, there were no pharmacies, nothing. Even those who were not sick on the day the boat clinics came would get their stock of precautionary medicines from them because we lived in a remote area and had to be prepared all the time.

One day in 2012, the boat clinic staff sent word that they wanted an ASHA worker from the community to help them. A meeting was held, and the villagers nominated me. I suppose they chose me because I was active in several Self-Help Groups (SHG) and moved around a lot in the village.

I was only 23 at the time but already a mother of two. I had been married very young, at just 14 and a half. I was keen to take on the responsibility, and my husband, who is educated and studied up to Class 12, encouraged me.

Were you aware of the work it entailed?

I had some idea of what an ASHA worker does because as a part of an SHG I sometimes saw ASHA workers in the village. Health officials told me that becoming an ASHA worker would help and that I would receive some benefits from the government. In those days, they paid us small amounts during health camps—sometimes Rs 50, sometimes Rs 100. After four check-ups, we would get Rs 100. The money was very little, but what made me happy was the respect.

Whenever I visited home, people—and it could be a much older man or woman—would greet me with respect. They would say: “ASHA baideo ahise, bohiboloi diyok (ASHA sister has come, pull up a chair for her). That respect meant everything to me.

I got a taste of this ‘respect’ a few years earlier–our village did not have a proper school so a local naamghar (prayer hall) was turned into a makeshift school by our villagers. My husband used to teach there, but later he had to go to Rajasthan to work as a migrant labourer. After he left, they asked me to teach. I taught there for six months, mostly basic things like the alphabet. It made me feel good and I felt respected. It also made me wish I had studied more. I studied only till Class 10, and, maybe if I had studied more, I could have been something else.

When I was in school, I always dreamt of becoming an ANM (Auxiliary Nurse Midwife). I always felt they look so smart and I dreamt of wearing that uniform, that coat, one day. So when the ASHA offer came, it was not a difficult decision for me.

What did your family say?

My in-laws were not so keen. They felt I would have to move around too much, go to strangers’ homes, and sometimes travel through isolated areas—all for very little money. But my husband supported me. He took me on a cycle to the hard-to-reach places. When I couldn’t write things myself, he would help me write them. Even now, if there are things I don’t understand, my husband tries to help me.

How did you join? Do you remember your first training?

Trainings were held to explain what our role was. They taught us things like at what stage of pregnancy a woman should be admitted to the hospital, when different injections need to be taken, and the ideal gap between two children. These were things I had very little knowledge of earlier.

I remember feeling scared before my very first training. It was held in a town called Lahowal, a journey of at least 7-8 hours (by boat and then road), but we were told that our stay and food would be taken care of. At the time, my daughter was only four months old. With no one to take care of her, I had to take my husband along for the training.

At Lahowal, when they saw that I had brought my husband along, they were surprised. They said: “Oh, you have got your husband along! But there is no place for him to stay.” I explained my predicament: was I to look after my child or attend training? It was slightly embarrassing because the other ASHA trainees with babies had bought female caretakers along. And there I was with my husband. But thankfully, the Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) there had a designated room for the ASHA workers, who needed to stay overnight, and that is where my husband was able to sleep. But he ate his meals with us and was the only man there among nearly a hundred ASHA workers. While I attended the training sessions, my husband took care of our daughter.

I paid close attention during the trainings. I was eager to learn and I listened carefully to everything they said. I remember taking detailed notes and learned about vaccination schedules, illnesses etc. Learning all this made me think that if I had access to an ASHA worker during my own pregnancies, I would have done things the right way, and my children might have been healthier.

How were ASHAs viewed in the village—was it difficult to get them to trust you?

The villagers were generally welcoming of the ASHAs. Our presence meant that, unlike earlier, there was now someone they could call in an emergency. Otherwise, they had to wait for the boat clinic to arrive. But there were still challenges.

Back then, many villagers did not have toilets and people would go out in the open to defecate, so we have to explain to them the consequences of open defecation. People often got irritated and would say: “Is it so easy to suddenly build a toilet? We don’t have the money.” Or when I used to go to new mothers and tell them about vaccinations, even that would be met with resistance. Post vaccine, if the child got a fever, the families—especially the men—would call us and scold us, saying: “What injection did you give our child? He is crying.” We had to patiently explain how vaccines work and their side effects. But on other days, I would stress out: what if the child was actually ill?

Those days I would feel sad: I would think about how difficult the work was, how high the stakes were, and how little we were paid, especially when people scolded us so much. On others, I would just laugh about it and try not to take it so seriously.

There have been incidents where the ASHA worker was beaten up too. During one training session, a woman narrated her ordeal: the child was given a vaccine, and subsequently got a fever and started puking. When the ASHA worker went to explain this, the child’s father chased her with a stick. Stories like these frightened us. We would call our seniors, who told us not to panic and to be strong. They advised us to warn people that if they refused vaccinations, the matter would be reported to the authorities.

What about your relationship with the other women in the community? Have you formed any bonds with them?

Sometimes I feel more like a confidante and a friend than a government health representative. When the boat clinics come, some women feel shy about telling the doctor their problem–then they turn to me, take me to the side and tell me the problem, whether it is a vaginal rash or other issue related to their private parts.

Because I visit their homes so often, a relationship has developed. When they see me walking by, they invite me to join them for tea or to have tamul (betel nut), which means they want to chat.

So they are very open with me and feel they can share whatever health problem they are facing. Once long back, when contraceptives were in short supply, they felt no shame in coming to me and telling me about it. That is so different from the initial years when the women used to be very shy when we used to hold awareness programs on using condoms etc. Many times, when a group of women needs to go to the PHC, they ask me to accompany them–simply for company. So our role is not just giving injections, it’s much more far reaching than that.

Has the remoteness been particularly challenging?

I bought a cycle four years ago, and it has made a lot of difference. I now cycle everywhere.

But before, I used to walk everywhere. I would eat a heavy breakfast and set out, on some days, to walk close to 15 km. I would get home only late evening and would feel so tired, I would barely be able to get up.

I look after five villages, and for one, you have to cross the river: I usually pay a boatman to take me across. Some parts are so secluded that even if you shouted, no one would hear you. To go from one village to another, I often have to pass through forested areas. Even within the same village, one house would be here and another far away.

So I saved money to buy a bicycle. I knew how to ride when I was younger but I had to relearn. It was a bit embarrassing: imagine a grown woman learning how to cycle, how it must have looked. I used to go with my sons to a secluded area, like a kohua bari (fields with tall wild grass), where no one could see us. I would ask them to give me support, I would fall, I would get hurt, but that is how I learned to ride again. Now it is much easier. What earlier took half an hour now takes only 10–15 minutes.

After I started using a bicycle, some people suggested that I should get a scooty. If only I could. I don’t have the money for it. We barely earn enough to feed our family and educate our children. The government had distributed bicycles, but I did not get one. I did get a mobile phone however. Sometimes we hear that the government may distribute scooters, so we are hopeful.

Does it get even harder during floods?

Yes, floods arrive every year, just after Bihu in April. During especially bad floods, the water stays for about 15 days. The flooding is so severe that taking a bicycle is impossible. The roads disappear completely. On those days, we depend entirely on boats and rafts. When the water is shallow, we walk, but many times it reaches our waist, and sometimes even our chest.

But we dress for the occasion: we wear old clothes and carry our uniforms and documents in plastic bags, because we always have to take a photo as proof that we went for duty. Many times we slip and fall, get injured, or are stung by snails. Our bags often get soaked.

During the pandemic, how did you navigate geographical and social constraints?

The pandemic gave us a new set of challenges. Our duties increased–the Assam government introduced a community surveillance programme, which meant we had to do door-to-door checks to check if anyone was ill or reported symptoms. Our seniors would keep calling us to check if we had gone.

Of course, I felt a bit scared because we were on the frontline. We had a mask on but it was still a little scary. Even so, I stepped out every day and left it in God’s hands. I kept reminding myself that this was public service, and that gave me the courage to keep going.

What became doubly challenging was when the floods hit during the pandemic. We had to sanitise ourselves, wade through floodwaters, and then return home to our families, making sure we did not put them at risk. At the time, there was a lot of praise for our work [from authorities] and talk of money being raised–but that never happened. The pandemic years passed, and then life returned to normal again.

What do you make of the financial remuneration for your work?

The money feels too little for the amount of work we do. Our fixed monthly income is around Rs 3,000 – Rs 2,000 comes every month, while the remaining Rs 1,000 is paid much later as a lump sum. Managing a household on such a low salary is very difficult for us, but there is nothing we can really do. When our payments are delayed, we go to the PHC and inform the seniors. Usually, they just say: “What can we do? The funds haven’t come in.”

For me, money has always been a struggle. I have five children—three daughters and two sons. I had my first child, a boy, in 2006. My second child was a girl. After that, my in-laws and my husband kept insisting that I should have another son. They would say, “What is the point of having just one son?”

As a woman, I felt I had no choice but to agree. At that time, I didn’t know any better…I was foolish. My own wishes and suffering came second. I got pregnant again, but I had a girl. After that, I finally had a son, and then another daughter. I used to think to myself: here I am, going around giving people advice and telling them the rules about childbirth, and look at my own situation.

It is true that women have more freedom in Assam, but it is also true that families still prefer sons over daughters. I see this clearly when I go to work in other households as well, even now. And you know what the irony is? Sons rarely take care of their parents—most of the responsibility falls on daughters. That is why I try to advise people; I tell them that boys and girls have equal rights, and that society should treat daughters the same way as sons, educate them, because in the end, it is often the daughter who takes care of you.

Because of the size of our family, we have had to depend on multiple sources of income. My husband works as a carpenter and is also a farmer. For many years, he worked in Rajasthan and Kerala as a migrant labourer but came back to Assam two years ago after my mother-in-law passed away. To make ends meet, we farmed. I earned some money through the self-help group, and we kept livestock—chickens, goats, cows—and sold milk. Whenever times were difficult, we would sell chicken. I also took loans from the self-help-group, or took on hajira (daily labour) work in the fields–that is how we survived.

Two years ago, we somehow managed to save enough money to buy a small piece of land in another chapori (Simen Chapori) about two hours away, where there are better educational facilities. We built a kutcha house there. Now my husband and the children live in that house, while I travel back and forth between our two homes. This is quite common in villages like ours—people who can afford it have two homes because there are no proper facilities for education here in Mechaki Chapori.

What did you do with your first salary?

The first salary I received was Rs 9,000, paid all at once about nine months after I joined. It was delayed payment, of course, but at that time Rs 9,000 felt like a fortune. It made me very happy.

I spent most of it immediately. I bought a small mobile phone, some things for the house, and a bag and a mekhela chador for myself. I also bought gifts for my family—my sister-in-law and my mother-in-law. I remember buying a thermometer and a weighing machine too. Those were for my work, but we were not provided with them and had to buy such things out of pocket. Now, even when I get money, I can never spend it on myself. The moment the money comes in, my children start asking for one thing or another.

Now my eldest son is 21. He is studying for his Bachelor’s degree and wants to join the army. My eldest daughter is 19 and is studying in high school. The other three children are still in school (classes 10, 5, and 3). Earlier, we had to rent accommodation for our son, which had increased our expenses even more. Now, at least, our children have a place to stay so they can study, and we can ensure they are educated.

For me, it is very hard to say ‘no’ to my children. For example, my son wants to join the army, and for that he needs to go to the gym. How can I say no to that? These days, when the children ask for things, I sometimes feel angry with my husband. I had said earlier that we should stop after three children because it would be very difficult for us to manage such a large family.

Do you get time to rest between your job and your family?

Nowadays it is better because we have a mobile phone–people call us up and immediately inform us when they are unwell. Earlier, no matter what every day we had to do home visits to check up on the patients. So yes, I do get some time to relax now. When I get some time, I watch shows on my phone or listen to music. Sometimes I also weave on the loom—making chadors (Assamese dupatta) or gamosas (Assamese towel).

Has your work ever felt like a burden?

Yes, it does, especially when senior officials speak to us harshly. Once, an official told me that in case of an emergency I should arrange a patient’s travel using my own money, and that he would reimburse me later. He would say “milai dim” — that he would compensate my expenses – but that almost never actually happened.

A few years ago during the monsoons, a pregnant woman moved into our area. She was not originally from here but had come to stay with relatives. She had diabetes as well as high blood pressure. One day she fell very ill and I was called. At that time, the area was flooded, so I waded through the water to reach her. Her condition looked serious, and the senior medical officer advised me to take her to Dibrugarh, saying that the expenses would be reimbursed later. I took her to Dibrugarh by boat and then by road, paying everything out of my own pocket. I admitted her to the medical facility and, for the night, I rented a room for myself, paying Rs 300. After that, I returned home.

The woman gave birth, but the child died three days later. When the officer came for the next medical camp, not only was I not reimbursed, he blamed me for not taking her earlier. He said the child would have been alive if I had acted sooner. I felt terrible and started crying. I even told him that he should hire another ASHA worker instead of me. The next time he came, he apologised.

We are used to things like this. We get hurt, but we also learn to forget. When I look at the people around me and see the difference I have made in their lives, I feel better.

Did you consider participating in a protest or joining a union?

I have never participated in a protest or even joined any union. It is just that we live in such an interior and remote area, that everything else becomes secondary. Moreover, I don’t have a network like that–so even when I do hear about a protest, I don’t have anyone to go with. It is not something I have really thought of. We just do our work, and that’s all.

What gives dignity and meaning to your work?

The single biggest achievement in my life is that I can buy things for myself with my own money.

Before I became an ASHA, I had to ask for money even if I wanted to buy a small thing from my husband. But once I became an ASHA, I had the chance to buy things for myself—however small, since the money was limited. But this feeling has been unparalleled, and I think the biggest change in my life.

As an ASHA worker, I am always on call–day or night, near or far. People know that I am there for them. That is why I am so respected, and it gives me a deep sense of dignity. Whether it is an illness or a birth, we are the first point of contact in such a remote area–and this responsibility is not lost on us, and even the villagers realise our value.

Want to participate in The ASHA Story? We invite ASHA workers, researchers and community members to share personal histories, research, and documents to help us build this digital archive. Write to us at contact@behanbox.com.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.