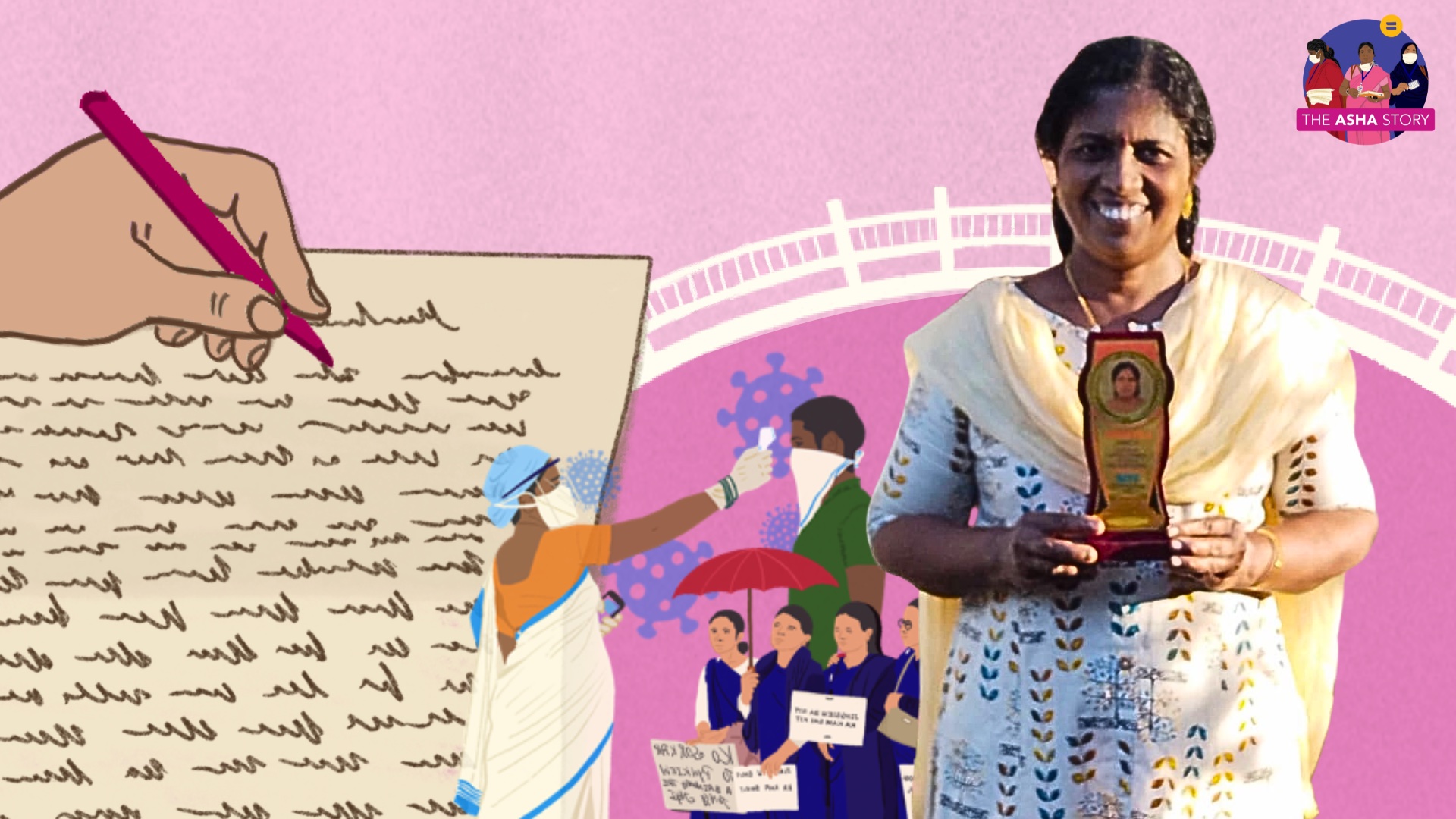

‘I Hope The World Sees More Of What We, ASHA Workers, Are Doing, And What We Can Do’

She dreamt of becoming a nurse, but it would take decades for Mini to realise a version of her childhood dream – when she became an ASHA worker in 2008. Mini’s journey is shaped by poverty, the pandemic and protests, but at its heart, it is about enduring hope. But stories like hers are sometimes better told by those who witness it closely. So we asked Mini’s daughter, Nimmi S, a writer and artist, to turn an intimate gaze on her mother’s life and work, placing care labour in context, acknowledging its aches and aspirations, and identifying the institutions that both sustained and constrained her.

As a Bahujan woman and a first-generation learner from Kerala, Mini was a member of Kudumbashree, Kerala’s ambitious poverty eradication mission and the largest network of women in the world, which shaped her identity. She spent decades toiling as a shrimp peeler before joining the ASHA programme. Speaking with her daughter, Mini reflects on the circumstances that informed her caregiving, the challenges of digital work, and ASHA workers’ historic protest in Kerala in 2025. There is pride in the work, but also hope for a future where labour is justly valued and formally recognised as ‘work’. Edited excerpts below:

When and how did you become part of the ASHA programme?

I joined in 2008. I was the secretary and an active member of our Ayalkoottam [neighbourhood self-help groups] at the time. Our Area Development Society Chairperson at Kudumbashree said she saw in the newspaper that health workers were being selected from each ward of panchayats. The same day I visited the nearby government hospital to enquire about it, they suggested I go to the Block Panchayat, where in turn I was told to submit an application to the District Panchayat at Alappuzha the next day. They said the age limit for application was 45 years, and I was 38 at the time, so I applied for it.

At that time, the term ‘ASHA’ wasn’t mentioned. There was a pre-test first, they asked health-related questions. I used to read the posters stuck on the hospital walls when I took my two daughters to consult doctors, so I knew of some of these issues. When they asked the name of the surgical procedure for male sterilisation I knew it was Non-Scalpel Vasectomy (NSV). I cleared all questions except one – I didn’t know the full form of ILR (Ice Lined Refrigerator, where vaccines are kept).

Soon after, I received a postcard informing me about a training session. It was for six days, and after the training, there was to be an interview. They asked me how many drops of polio are given to children and about my work as a member of Kudumbashree. I used to volunteer to accompany one of the sisters from the Public Health Centre (PHC) while marking the houses where children had been given polio vaccines and to distribute medicines for diseases like filariasis.

After a month or so, the panchayat informed me that I was selected from my ward.

What was the training like, and how has it changed over the years?

The training gave us so much confidence. They told us that we are not just housewives, and from now on we will hold an important position in our society. They also trained us how to interact with people in the field, how to be empathetic, and keep personal details confidential because that’s how we gain their trust. We also got an idea about our roles and responsibilities. They told us about the Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY), and our responsibilities of ensuring nutrition for women and children, ensuring immunisation vaccines, and more. After that training we got an ASHA identity card, a diary, a pen and other things. In the training, they mentioned the rewards we would earn for each activity, such as Rs 20 for immunising each child. This hasn’t been increased by a single paisa after all these years.

I started working in the field a week after the training. There was a conference for ASHA workers in our panchayat before that, where we were introduced to the PHC staff, and a JPHN [junior public health nurse, or an auxiliary nurse midwife in other states] was assigned to each group.

The next training was two months after the first one. We had made commendable progress through our service to the health sector of Kerala – no, India – even within this short period. The rate of immunisation among children shot up, more women were delivering in government hospitals. A lot of things changed, and we were proud of them. We got a lot of appreciation in the ensuing training sessions and our confidence was increasing. We completed 10 training modules.

We started getting the promised honorarium of Rs 500 after a year, but we also got incentives – Rs 150-250; Rs 75 for polio work. I remember we had to sit for an entire day at the polio booth, and I felt extremely proud while sitting there. I loved it.

How did you become interested in being a health worker?

I had been working as a shrimp peeler since I was six years old. Even though I studied until pre-degree, I couldn’t find any other job. After marriage, I thought I would never have to do this. But I had to take care of my two children. There was no one except me to look after them. I went back to peeling shrimp after they started going to school, so that I could go to work and be back by the time they were home. Our financial conditions were very bad. It’s not that I didn’t try for other jobs, but at that time, my thoughts and perspective were limited. I searched for daily wage jobs like seafood packing. I was constrained by household chores and care responsibilities. And honestly, I didn’t have the confidence to look beyond that.

My arthritis was also getting worse back then. We had to sit on the floor in the peeling shed, surrounded by big blocks of ice, and our working conditions were worsening.

I gained confidence and leadership qualities when I joined Kudumbashree. That’s when chechi (the ADS chairperson) told me about the opportunity for ASHA workers. She was a dear friend and comrade. I was the one who joined her in our self-help group. She later contested panchayat elections and won from our ward. I began working as part of MGNREGA schemes when it later started, doing whatever job was available.

I saw the ASHA role as an opportunity to get out of this. During our first training it was told that we would get Rs 500 as monthly honorarium. Even though it was a small amount, it was a relief for me. I used to earn only Rs 150 weekly with shrimp peeling. I was running the house with that meagre amount of money. Plus, it is a government project and I felt like this is a meaningful position. In the training it was told that it is not a job, but a voluntary service to society. I loved what I was doing and I never wanted to go back to shrimp peeling.

What did you make of the delayed payments and ‘volunteer’ status?

In our training we were told that our work is flexible. I believed things would improve gradually because it is a government project, and we were also getting respect from society.

For me, this work is also close to my heart because I wanted to become a nurse. It was my dream. One of my cousins got into BSc Nursing, but I couldn’t pursue it because of financial constraints. She later became a nurse in one of the medical colleges in Kerala. Being an ASHA worker somewhat fulfilled my dream of working in the health sector. It was the love for what I was doing that kept me going. I still love what I do.

What were some of the challenges that you faced during the initial phase of work?

It was difficult to work on family planning – motivating men to get vasectomy rather than [placing the load of contraception on] women. And initially people were not that welcoming when we went to the field. But as we visited frequently, we gained people’s trust. We were so welcome that ASHA workers were considered for panchayat elections. People used to encourage me to contest elections, but at that time I had a lot on my plate. I was taking care of my family in every possible way, including supporting them financially. My purpose also aligned more with ASHA work than with being a political leader.

At that time we neither had phones nor a bank account. We used to get the honorarium as cash directly from the PHC. Later bank accounts and phones got linked with the National Health Mission. You know what, my phone number is registered in Delhi too.

When did you start using a phone and what was your experience of working with them?

My first phone was a keypad phone that cost about Rs 600. I didn’t even know my number. The staff at the PHC used to make fun of us when we got messages from the Prime Minister, addressing us as ‘ASHA Behen’. I bought a smartphone in 2018, nine years after our first training, because it became very essential to our work. But I had to learn how to pick up a call, how to save a number in the contact list, and how to send a voice message on Whatsapp. It was difficult and took some time to pick up these things. Some older ASHA workers found it very difficult to operate smartphones.

But after learning the basics, I started feeling comfortable with smartphones. People could send documents through WhatsApp, we could pass important information by putting voice messages. After we got smartphones, communication was mainly channelised via WhatsApp and groups were created for different purposes. We were also added to other WhatsApp groups in panchayat, and it felt like we became an integral part of every social activity in it.

At the same time, the workload had become more laborious.

What was your experience as a frontline worker during Covid?

It was scary. No one had a clue what to do in the beginning. We watched news of people dying of Covid-19 but we couldn’t be scared; we had to step out, we were ready to do anything. But when I look back, it was the toughest period in every sense.

My phone used to ring continuously, day and night. People were afraid. The number of Covid positive people was increasing day by day. We had to ensure social distancing and protective measures. We were risking our lives but we made sure we took enough protective measures – we wore gloves and masks, used sanitiser, washed hands every time, taught people how to wash their hands, reminded them to wear masks, and delivered medicines to those who tested positive. We were there, in PPE kits, even at the cremation of people who died of Covid.

ASHA workers are the data bank of the health system in India. We had data on who were more vulnerable to diseases in each locality so we acted as intermediaries between the first-line treatment centres and patients. We ensured people observed quarantine properly, even delivered food and groceries. We lent a shoulder and an ear to people in distress, both mentally and physically. We did whatever we could.

In our ASHA worker field diary, there are photos of ASHA workers who died due to Covid. They are our warriors. That shows the kind of risk we took during pandemic.

The work load peaked after the vaccine came. We had to deal with hundreds of calls every day. Lists were made of people that should be vaccinated on priority basis and we had to encourage them to take the vaccine. There were conflicts too: some wanted Covishield and some wanted Covaxin. All these things were not in our hands. Some people thought we were favouring a few but there was a priority list of who was more vulnerable.

There was a lot on our plate, more than we could handle. I also think that was a time when ASHA workers got worldwide attention for their work.

Governments increased honorariums during Covid-19 and bestowed awards. What do you make of this recognition?

We were getting only Rs 5,000 as honorarium during Covid-19 time and Rs 1,000 from the Kerala government as Covid-19 allowance. There were no fixed working hours per se. Initially, it was said that our work would be flexible, but it is not.

I am grateful for the appreciation and recognition we got during Covid-19 but honestly, I would feel appreciated and respected if we are recognised as ‘workers’, not volunteers. Our labour needs to be recognised and we want wages instead of performance incentives and ‘honorarium’. When we talk about how severely underpaid and exploited we are, some officials who get fixed salaries to work fixed hours say: “Aren’t you volunteers? What you do is service, right? You joined the ASHA program knowing this, right?” That is hurtful.

Some of my fellow ASHA workers have left the work because they couldn’t survive with the current money we get – especially those taking care of their family. I have multiple loans to pay every month and this is my only source of income. Sometimes I think if I had a job with better salary at a fixed time every month, I wouldn’t suffer this much. Our debts don’t wait for the date the honorariums are credited to our account, do they?

How much of your work now happens online? Has it impacted your participation/trust levels within the community?

A lot of work now happens both online and offline. We have the Shaili app, which is completely online, the SASHAKT app [for training], and many reports are now submitted through WhatsApp. Even though online work is inevitable nowadays, I don’t think all ASHA workers are equipped to do it. Working through apps is difficult as we are not used to them, and it takes a lot of time and effort to learn.

Personally, I feel that offline interaction with people builds more trust and connection but at the same time, being able to text people on WhatsApp and submit reports online has reduced the physical labour of going to the field.

Recently, it was us ASHA workers who conducted the survey to identify people coming in the extreme poverty list in our areas. [Based on these surveys the state government declared Kerala “free from extreme poverty” in October 2025]. Since we are very familiar with the areas and its people, I was able to enrol deserving people on the list. I am very keen on participating in social issues. I understand that my role as an ASHA worker is expanding and evolving, but I am aware that the labour is not rewarded according to the workload.

ASHA workers in Kerala last year were on strike for more than 260 days for enhanced remuneration and retirement benefits. What was the movement like?

The protest, when it started, gained a lot of attention everywhere; many people from my area reached out, saying that they didn’t know ASHA workers earned such minimal income despite their commitment to work. The issues raised—honorarium, workload, working hours, and leave—applied to ASHA workers all over India. However, I had many differences with the organisers of the protest. They were cornering the Kerala government, while it is actually the central government that has to make the policy changes related to ASHA workers. When protesting for labour rights, I stressed that ASHA workers are considered volunteers, not workers, by the central government.

Also, when Suresh Gopi, MP from the BJP, came to the protest site [to distribute umbrellas and coats], the whole idea of the protest became contradictory.

You are one of the most hopeful, cheerful people I know and you face hurdles gracefully, and always with a grateful heart. I always wonder how you do that. It’s been 17 years since you became an ASHA worker. What do you want to say about this journey?

It wasn’t an easy journey; I have learned a lot, I am learning every day. There were days I touched rock bottom but I am always proud of this journey. Looking back, I have gained confidence and skills through this work. The interaction with people and the respect they give, and the feeling that we are an inevitable part of the social and health system of our country, gives me motivation to continue.

I feel content and happy about what I do, what I can do as an ASHA worker. I am extremely proud of the work I do. And even though the reward is not enough, the feeling of getting our hard-earned money credited into our accounts is the fuel that keeps us going. I am doing many things with that money. People might think it is a very small amount but it is very necessary for my survival.

In the end, it is the self-respect and validation that give me hope to move forward. Everyone in the panchayat now recognises me as an ASHA worker. And I hope the world sees more of what we are doing, what we are capable of.

[Read this illustrated essay by Nimmi S on the life of her mother Mini.]

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.