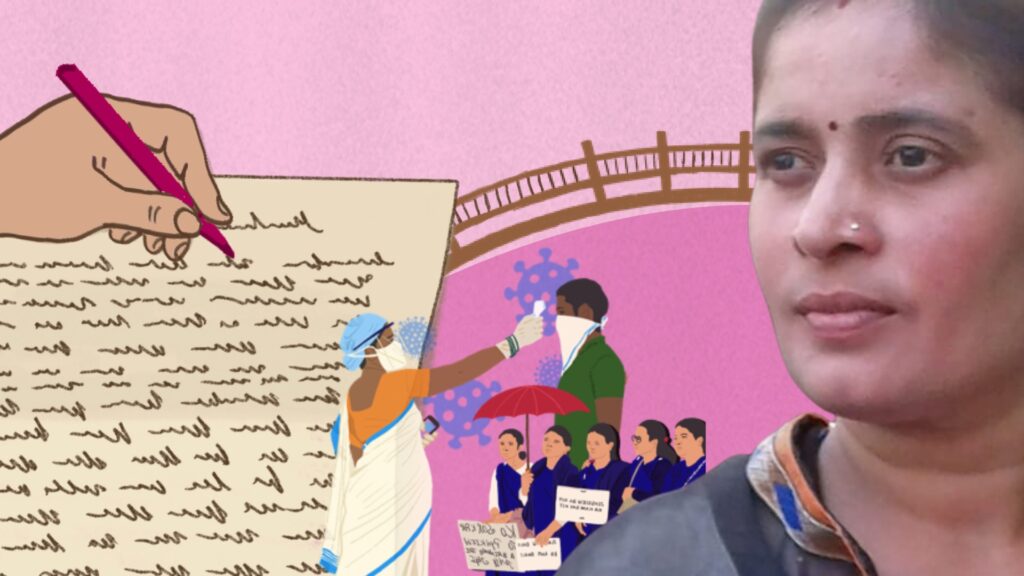

Since childhood Lakshmi Kaurav had dreamt of becoming a doctor. So in 2005, when she heard that a new cadre of frontline health workers was being set up, she thought she would somehow inch closer to her ambition. She was allowed to study only up to the 10th grade and at the very least, this job would allow her to study without asking anyone for money.

This was the year the ASHA programme was launched by the government with no clear idea of the contours it was to later acquire. “At that time, there weren’t even proper forms to apply, and it was done by submitting a basic motion during the gram panchayat meeting. In my case, my chacha (uncle) and sasurji (father-in-law) were panchayat leaders and they submitted a proposal, noting that I am 10th pass. The panchayat agreed and that’s how my name was picked,” she recalls.

The selected women would then be interviewed by an NGO assigned for the task of recruiting and asked to take an oath. “If someone could write clearly and quickly, it was assumed they were capable enough to be an ASHA worker. If someone couldn’t write but had no other competitors in their village – because not many wanted to do this work – they’d still be selected,” Lakshmi remembers.

A lot has changed since then. The ASHA work profile has expanded several fold – from the basic tasks of ensuring maternal and child welfare to now assisting in the election process and doing critical groundwork during emergencies like the pandemic. All the issues that once seemed acceptable – being called volunteers, not being on government rolls, being paid paltry money and with no avenue for welfare benefits – are now deeply hurtful for ASHA workers.

Lakshmi today leads ASHA workers as a union leader, leading protests, representing them on national and international forums and giving their grievances a strong voice. But it has been a tumultuous two decades for her and the cadres. In our ASHA Project series, we interview Lakshmi to document these decades and what changed and what has to change. In the process we discovered some fascinating insights into what it was to be a worker in a freshly minted cadre all those years ago. There was little or no training, workers walked into the field and slowly figured out their roles, their mission was misunderstood, they dealt with suspicious community members, and struggled to communicate with villagers about family planning and other sensitive issues.

“We were expected to motivate both women and men to consider sterilisation, use contraceptive devices, oral pills, and condoms. Training mein yeh cheezein sunne mein sharam aa rahi thi. I was still one of the more educated women there so I didn’t feel too embarrassed but the other women – some of them covered their faces with their saris, looked down, or put their hands over their mouths,” Lakshmi remembers. Then there were domestic responsibilities and family opposition to deal with.

But Lakshmi is now a confident organiser and motivator, at the forefront of the collectivisation efforts of the ASHA community. Saumya Kalia interviews her on the long road ASHA workers have travelled since 2005, both personal and professional.

Read our interview here.