How Film, Literature And Art See The Lives of Delhi’s Informal Women Workers

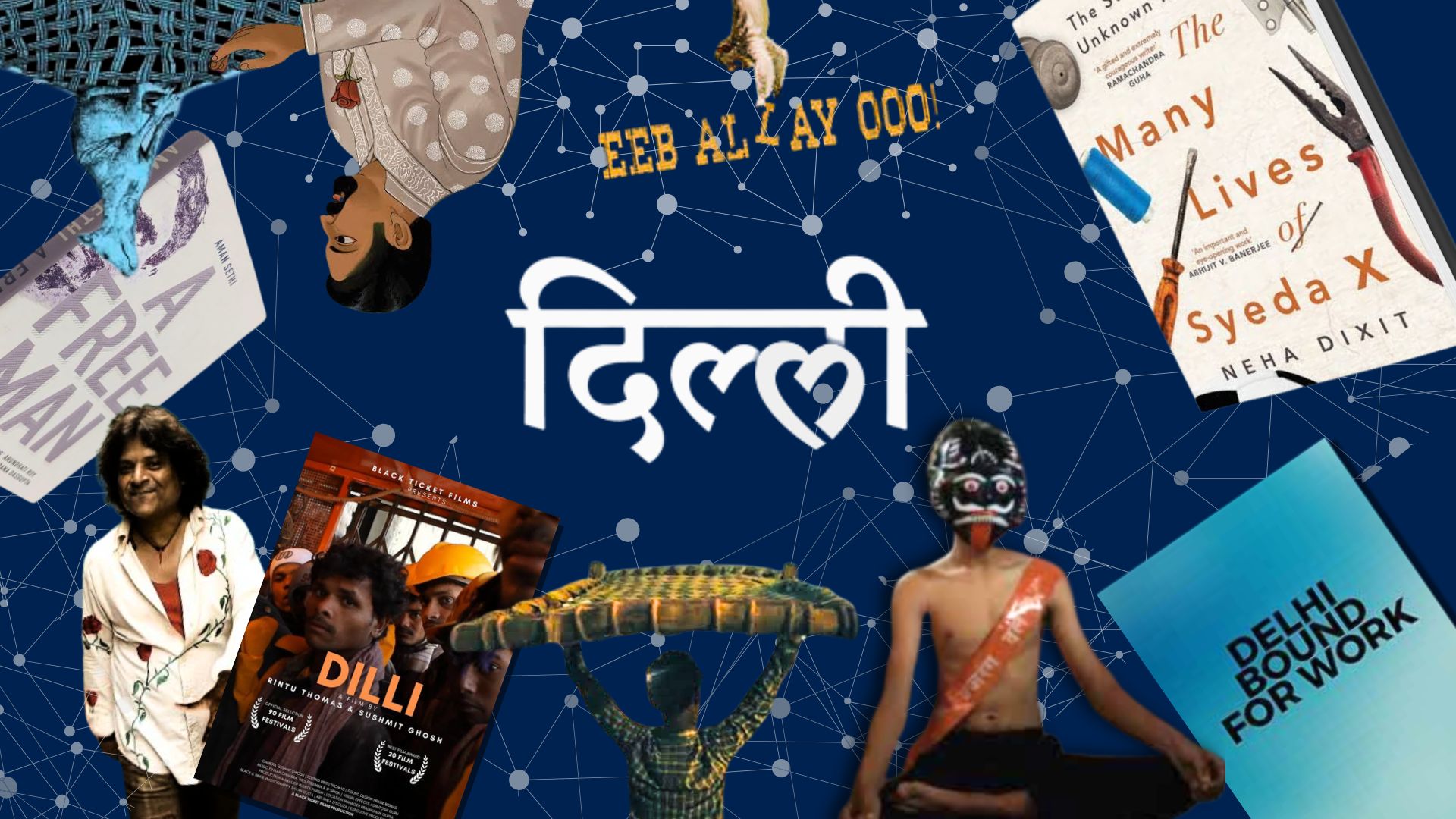

In popular culture, Delhi often remains a cliche. You rarely see its informal women workers except as footnotes. We have compiled here a list of films, books and art works where their unseen lives are recorded with veracity and compassion

On any given day, at least 4 million people work to keep Delhi running. You see them every day, everywhere, working with deft hands, weaving the fabric of India’s capital city. What are their stories? Let’s say they are migrants who came to Delhi, never to return, or locals displaced from jhuggi jhopris, pushed to the city’s periphery. Maybe some came here to flee communal violence, others to escape extreme poverty. Some dream of success as they subsist on daily work while others join resistance movements. Some sweep roads, others shell almonds, many build homes, or work in them. And all this while they are breathing Delhi’s rotten air or battling intense spells of heat and cold. But what are their fears, triumphs and tragedies?

In popular culture, Delhi lends itself to extreme depictions. Films record its extravagance, corruption and impoverishment while books fixate on the Walled City’s historic charms and Lutyens’ power corridors. The lives of informal workers are either missed or recorded as footnotes. Migrant women workers are often erased altogether from collective perception.

But some stories challenge this lack of imagination. We look at narratives that show people’s experience of Delhi, one of the biggest centres for small-scale industries today, in stillness and motion. And in both they struggle against poverty, migration, displacement, unemployment, casteism, and globalisation.

We have compiled for our readers a list of books, art works, movies and documentaries that tell extraordinary stories of Delhi’s ordinary people. It is by no means a definitive list. But here you will find playfulness and humanity, and a record of people’s loneliness, desires and hopes.

A Free Man by Aman Sethi

A book on how the city’s sheen hides stories of displacement and loss

Delhi was on the cusp of significant economic changes in the 2010s, and its ethnographic story is told here through the eyes of a small group of itinerant workers. In the run up to the Commonwealth Games, “Delhi looked like a giant construction site”, the rubble marking the “incredible changes and dislocations of factories, homes and livelihoods that occurred as Delhi changed from a sleepy North Indian city into a glistening metropolis of a rising Asian superpower”. It is estimated almost 2.5 lakh people were evicted from their homes as Delhi’s contours changed. Among them is Mohammed Ashraf, a 40-year-old tailor, whose life and friends became the focal point for Sethi’s investigation.

The four-part novel unfolds in Sadar Bazaar, a sprawling market populated by painters, sales, repairmen, rickshaw pullers, mistrys and mazdoors, who squat every morning at the Bara Tooti chowk and wait for contractors to hire them for daily work. It is on these streets where many like Ashraf “live, work, drink, and dream”. And it is here where Sethi records work-weary hands, zooms in on faces, and then steps back to frame people’s lives in the larger context of their identity, dreams, and community. Ashraf’s story starts with azadi (freedom), but then starts the gradual decline into loneliness, abandonment, and estrangement as the “state’s neoliberal policies bring about socio-spacial transformation” in the city, noted this review. In Bara Tooti a community forms of people, who are disaggregated during the day by jobs, but are bonded together by friendships, failures, loneliness, and the dreams of making it big.

This non-fiction account is as much as Mohammed Ashraf’s story as it is of a community overlooked in Delhi’s transformation.

The Many Lives of Syeda X by Neha Dixit

A book on the faceless migrant women who juggle several jobs in a day

Journalist Neha Dixit takes us to what Delhi calls “Jamna paar”, east of the capital city across the river Yamuna, into the life of Syeda, a Muslim, female migrant worker. Syeda moved to Delhi from Banaras after communal violence that broke out in the aftermath of Babri Masjid’s demolition. She moved several times in the metropolis, “settling into the life of a poor migrant, juggling multiple jobs a day”. Over 30 years Syeda has done more than 50 home-based jobs – from shelling almonds to trimming jeans. Home-based work is the largest working sector for women after agriculture. Life comes to a “grotesque full circle” for Syeda when the 2020 riots in northeast Delhi cause her to move again, a displacement triggered by both economics and majoritarian politics.

Written over nine years and with inputs from more than 900 people, the book tells the story of informal workers, specifically women migrants. Up to 82% of all working women are concentrated in the informal sector, and women’s home-based and informal work is key to the functioning of Delhi’s industries.

But up until 2008, India’s laws for migrant workers did not recognise women; the average monthly income for many remains less than a quarter of Delhi’s legal minimum wage. The book sees Syeda and many women like her in the context of poverty, gender, social bigotry, and globalised markets. As it fluctuates between hope and despair, we see individual triumphs (for instance when Syeda joins a union) but no signs of systemic support for the women. Still, characters never become victims; Dixit shows them as “real people, oppressed, exploited, and yet able to sometimes negotiate with power, and other times defeat it by just stepping away, and on rare occasions, confront it, vent their anger at it, and win the battle,” as feminist activist Urvashi Butalia wrote in her review of the book. These are individual triumphs, but the promise of the city remains unmet; “Dilli bahut behudi (Delhi is gross),” as one character laments.

In this account of urban life in Delhi, many readers will find themselves complicit in enabling the systems of exploitation that shape Syeda’s many lives.

Dilli by Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas

A documentary on the schizophrenic divide between Delhi and Dilli, the rich and poor

Displacement is a recurring lens in this 2011 documentary that weaves together interviews with slum dwellers – many of them beggars, street vendors, and daily wage labourers – who were evicted from their homes when the city was overhauled for the Commonwealth Games. The homes of thousands were bulldozed from and those displaced were moved to resettlement sites such as Bawana, an area without shelter, drainage, and food.

Commuting from Bawana to places of work was a challenge because of the distance, cost and abysmal public transport facilities, noted a 2011 fact-finding mission report. The report also flagged grave human rights violations – construction workers being denied minimum wages; beggars being arrested and forcefully banished from the city and street vendors denied the right to work. [The industrial site of Bawana faces several issues today, including toxic waste disposal and rising air pollution.]

Some of these accounts are recounted in Dilli, which further probes the idea of belonging in a city of migrants. “Raat ko so bhi nahi paate the, din mein apna ghar chhod kar jaa bhi nahi pate the (we can’t sleep at night and can’t go anywhere during the day),” one woman says, referring to the fear of fire hazards in the cramped settlements. Directors Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas also contrast the gleam of modernisation with the grief of those left behind. “Delhi hum jaante nahin, Delhi kya hota hai. Dilli jaante hain, yeh mera shehar hain (We don’t know Delhi, we only understand Dilli, which is my city),” one person says.

Cities of Sleep by Shaunak Sen

A documentary on the politics and economics of repose for the poor

Shaunak Sen’s maiden documentary documents the politics of rest and relaxation among Delhi’s homeless populations – many of whom beg for a living or are daily wage workers. Sen documents the shadow worlds of Meena Bazaar and Loha Pul over three years to portray the dual economies of ‘sleep mafias’ and ‘sleep cinema communities’. The protagonists include Jamaal, a tea seller who runs a sleep mafia charging Rs 40 and upwards for a night’s rest; Ranjith, a rickshaw-puller who runs a sleeper community on a strip of land under the Yamuna bridge; and Shakeel, a homeless beggar struggling to secure shelter.

Sen’s second feature-length documentary All That Breathes won accolades for its meditative gaze on urbanity. In this work too, he synthesises cinema, art, humanity and sociology to probe the privilege of repose, asking who gets to sleep and where. Shakeel experiences this world as an outcast: he is a Hindu man who lies about being Muslim just to find a night’s rest in Meena Bazaar. Jamaal’s ‘sleep mafias’ are coercive and exploitative at times, but are a basis of sanctuary for people forced to live in the open.

In Loha Pul over time, community and camaraderie have flourished – people have opened a bank account under the name of ‘Sleepers Fund’ which comes to the aid of anyone who falls sick, even an official electricity meter. A social contract that is activated when people come to sleep together, “a basis for a kind of kinship and safe sanctuary for the people there”, Sen said in an interview.

The documentary ties together sleep, work precarity, community and freedom. “Only the man who sleeps and wakes as and when he wishes is free in the truest sense of the word,” says a character.

Delhi Bound For Work by Reena Kukreja

A documentary on the intimate lives of domestic workers

The backstory to Delhi’s vast network of domestic workers is captured in this 58-minute documentary by scholar-activist Reena Kukreja. Almost 5 lakh women provide care work across Delhi today, shuttling between houses, working for over 40 hours, without a standard pay or safe work conditions. The filmmaker zooms in on women like Pratima Baa who migrated from Bihar, finding a path out of poverty and early marriage. Reena, who has produced other films about gender and migrant cultures also probes the role of exploitative placement agencies and employers.

First released in India and Canada in 2008, its relevance has been incrementally established over the last few years – there are frequent reports of young girls and women being harassed within homes. Domestic worker unions have been urging the government to recognise their labour and extend social security protection under labour laws.

However, in the midst of this despair, Reema also pauses to gaze at the intimate dreams and destinies the women expect to realise in Delhi.

God On a Leash by Varun Chopra

A documentary where faith meets politics and economy

It is a familiar spectacle at Delhi’s Hanuman temples: ‘performances’ by a child mimicking an ape, and a monkey trained to behave like a human. These two separate ancestral art forms – practised by members of the madari and behrupiya communities – are tied to the veneration of Hanuman. Filmmaker Varun Chopra’s documentary traces their lives and the influence of fate, faith, and poverty in shaping their survival. Most of them live in areas like the Nirankari Colony jhuggi, in abject poverty. At Nirankari colony, a madari told Chopra that he’ll put a leash on his child when he grows up and train him. “The future of this baby monkey seemed bleak, sort of set in stone,” he told The Quint.

God On A Leash represented India at Cannes in 2016.

Eeb Allay Ooo! by Prateek Vats

A satire on the absurdity of contractualisation of jobs

In Eeb Allay Ooo!, the tragedy of Delhi’s migrant workers is defined through the corrosive nature of contractual work, majoritarian politics, and sectarian violence. It follows the life of Anjani who joins a squad tasked with chasing macaque monkeys out of government buildings with the warning sound ‘eeb allay ooo’. But the monkeys cannot be hurt in the process because they are associated with the deity Hanuman. By the end, Anjani is disenchanted by Delhi’s promise. This “absurd fiction” tells the story of “people who make our cities, our houses, what they are, but remain invisible”, director Prateek Vats said in an interview in The Times of India.

The film’s primary preoccupation is with the migrant workers, their dignity and community. But it also holds space for desire and dignity. Anjani falls in love in these narrow lanes; he also finds a mentor.

Decades ago the bogey figure of a ‘monkey man’ was supposed to have haunted the city’s working class neighbourhoods. This has since been dismissed as a case of mass hysteria. But scholar Akhila Kumaran believes that this is one of the many ways in which the “working class people continue to find ways to not be completely invisible”.

Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Ke Liye Jaa Raha Hoon by Anamika Haksar

Magic realism meets everyday life in this movie

Clogged drains, dizzying crowd, and the crammed lives of Old Delhi. Through theater doyenne Anamika Haksar lens, the Walled City of Shahajahanabad sheds its history and old world romanticism to lay bare the lives of people who have no roots here. Ghode Ko… portraits the “extraordinary amalgam” of life in Shahajahanabad while also capturing the struggles of survival and dignity. It employs almost 400 residents of the old quarter and almost 80% of the dialogues come from its people.

The 2018 movie is told through four central characters: Patru the pickpocket, Lal Bihari the labour activist, Chhadammi the street food vendor, and Akash the heritage walk guide. Folk songs fly in the air and folk stories stroll down the streets, as one character says, perhaps because this is home for those who have been displaced. The movie is a product of over seven years of research. The title has its own story: the filmmaker heard a 35-year-old anecdote from her aunt who used to go to Purani Dilli to learn Hindustani classical music. “Once she hailed a tonga and asked ‘Arre bhaiya kahan jaa rahe ho (where are you going)?’. And he responded, ‘Arre bibi, ghode ko jalebi khilane le ja riya hoon (I am taking the horse to eat jalebis)’.”

There is whimsy in the film’s storytelling, magical realism blending with the documentary approach. “Haksar’s screenplay blends an unusual narrative rhythm with an infectiously Aesopian spirit to underscore the potential of song, poetry and fable to form a bulwark against the deleterious effects of poverty and social inequity,” wrote film critic Saibal Chatterjee.

Hawa Mein Baat, A Collective Artwork

An artwork on women’s relationship with climate change

Hawa Mein Baat is an autobiographical artwork, documenting the lives of 20 women from Delhi’s informal settlements, Bhalswa and Nand Nagri, grappling with its polluted air. It is also a demand to see women as equal stakeholders in conversations on climate action.

The majority of women in informal sectors are engaged in low-paying and unpaid work such as home-based jobs, waste picking, construction and domestic work. Their occupations, geographies, infrastructure, and social locations determine how often they go out, and how much they are exposed to dust, sand, and poor air. Women in Delhi’s construction work shy away from discussing their experience of air pollution fearing repercussions from their employers, said a 2022 study by Mahila Housing Trust. Confined homes and poor ventilation in slum settlements has also been found to disproportionately impact informal women workers.

The exhibit included textile art, objects and poetry, as women came together to discuss their relationships with precarious work, climate change, and their cities. Anita Devi whose work was on display said in a report: “I was able to take out time for myself. I enjoyed doing the silai (stitching), sitting with other women and discussing our challenges.”

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.