[Readmelater]

In Rural Madhya Pradesh, Women Struggle To Access Govt Schemes Aimed At Them

The Madhya Pradesh government is going all out to woo women with special schemes. But how do the women see this outreach, we ask

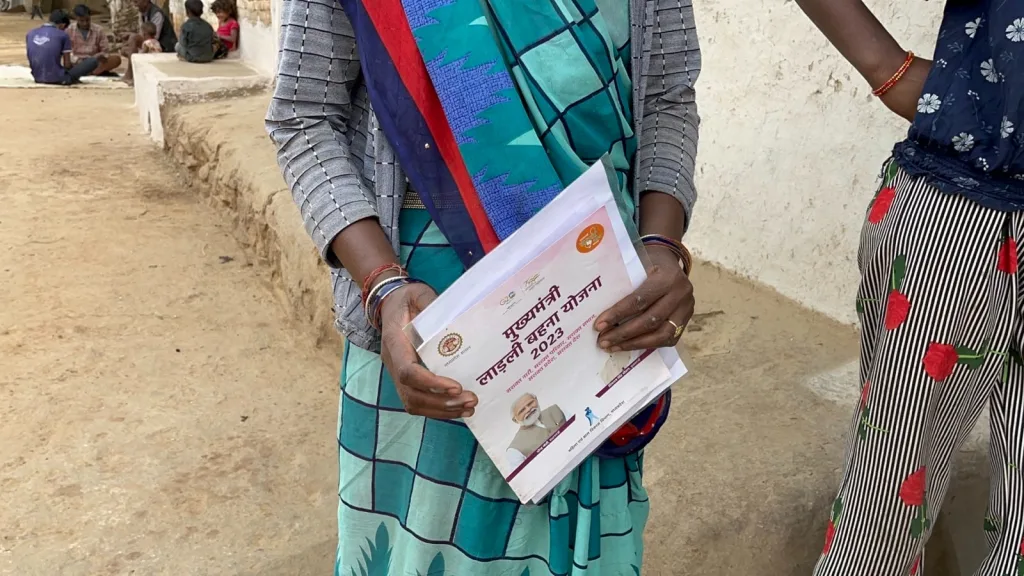

A woman outside the Kunwarpur panchayat office where applications are submitted for the Ladli Behna Yojana, Panna, Madhya Pradesh. Credits: Khabar Lahariya

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.