The toxic gas that killed and sickened thousands of people in Bhopal never really left their bodies. And 41 years later, its aftermath has not stopped blighting their lives. It is hard to find the right words to describe the miscarriage of justice that the survivors continue to suffer – the abysmal compensation, the loss of livelihood and the utter callousness with which the state treated their medical needs. Above all, they have to watch as the perpetrators not only go unpunished but also spread their tentacles elsewhere.

As is always the case with such catastrophes, it is the women of Bhopal who were left to shoulder the terrible consequences. From working class, marginalised homes, many of them had little education, job skills or mobility. But with family breadwinners either dead, bedridden or very sick, they had no option but to step up and radically transform their lives and hold up their loved ones.

BehanBox is marking the 41st year of the catastrophe with reports on the long, hard battle that is being waged by the survivors. In the first of these, published this week, we look at how the crisis did not end the morning after the gas leak but continues to affect multiple generations of those affected.

Leela Bai remembers everything about the night of December 2, 1984. She was a young mother, asleep in her mud-walled home, her husband and in-laws nearby. Her one-year-old daughter woke up crying; then came the burning sensation as though chilies were being rubbed into their eyes.

Leela ran barefoot into the darkness with her baby, the air white with thick smoke. “People were screaming, collapsing, vomiting. We ran over bodies. The whole mohalla was empty and full of death,” she recalls. “Every time we tell this story, we live it again.” But it was not as if the deaths and disasters ended that night. The gas seeped into their lungs, into their drinking water, into their pregnancies, and into the bodies of their children and grandchildren.

Vishnu Bai never really recovered. She has high blood pressure and breathing problems. Her husband, who was heavily exposed the night of the leak, died 20 years later from lung complications related to tuberculosis. One of her sons, born after the disaster, developed severe anxiety and died by suicide. We found several such stories.

The Union Carbide factory still stands at the same location, pipes rusted and twisted. But perhaps most disturbing is the toxic waste that still seeps into the soil and the groundwater. For decades, large quantities of hazardous waste abandoned at the site have been swept by rainwater into the groundwater in the neighbourhood. In certain neighbourhoods in a 5km radius of the abandoned factory, contamination is still ongoing. It is so severe that some soil samples near the factory taken in the past contained mercury levels up to 6 millions of times above permissible levels. Gas exposure was the first disaster; groundwater contamination has become the second.

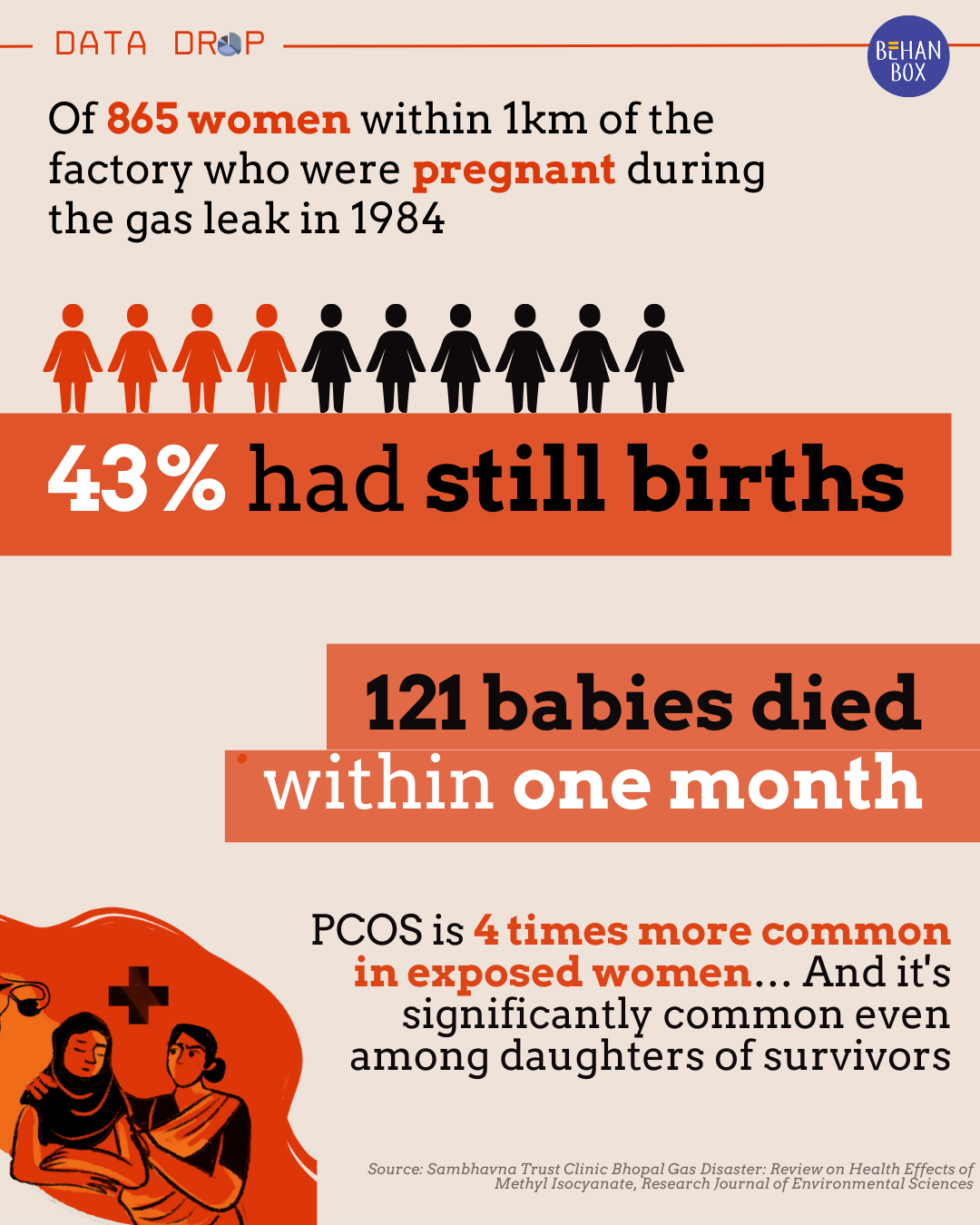

An academic study was carried out in 1996 on the consequences of the gas leak for women’s reproductive health. It found significantly higher rates of pregnancy loss and neonatal deaths and persistent gynecological disorders among exposed women.

It was not the state-run ‘gas relief hospitals’ that helped patch up broken lives. It was the tireless work of trusts like Sambhavana and Chingari and women like Rashida Bee and Champa Devi Shukla, who put their own grief aside, and stepped up to provide help to women and children in distress. In the second part of the series, we profile their tremendous work.

Read our story here.