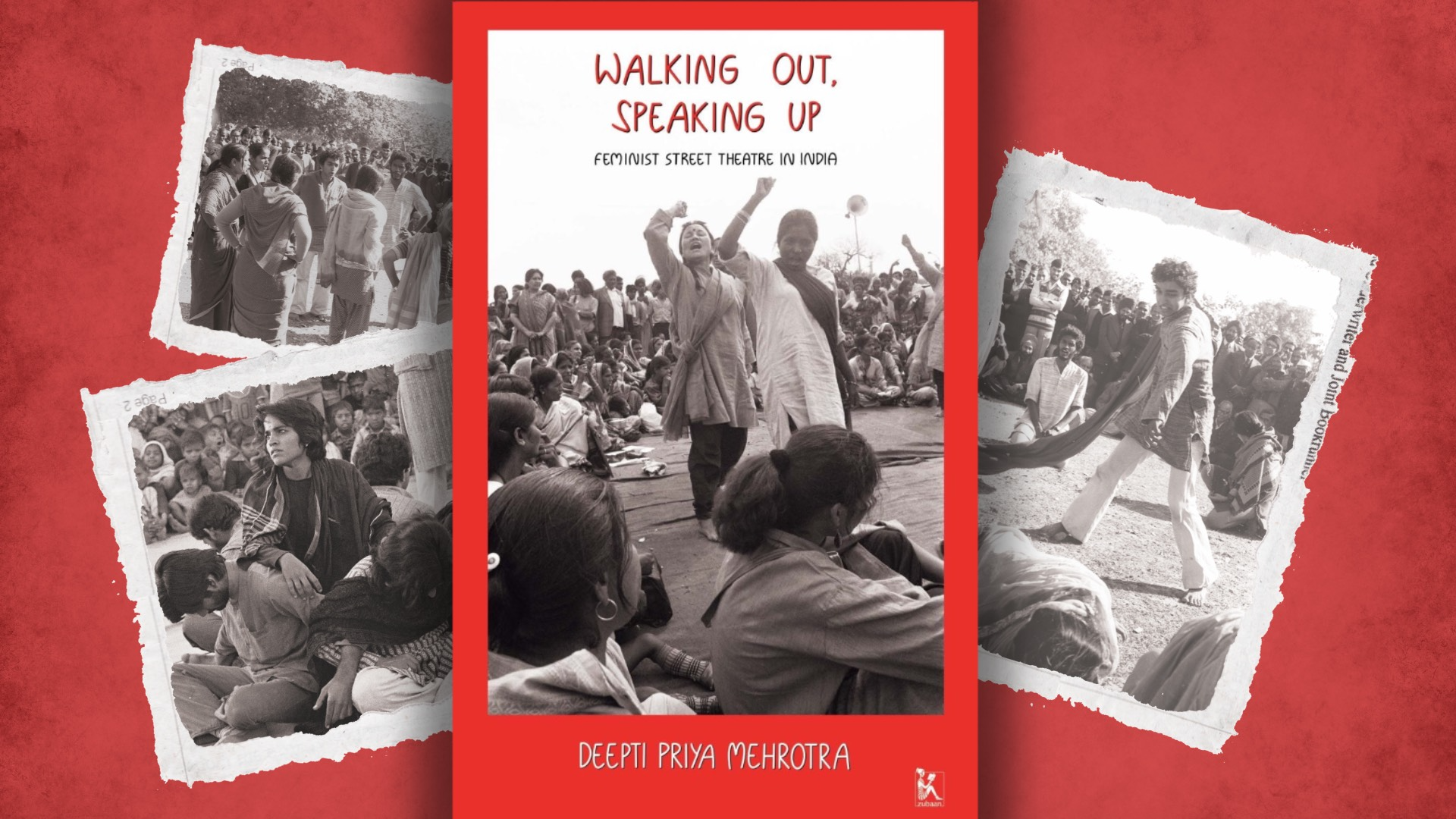

Om Swaha: The Play That Birthed Feminist Street Theatre In India

Excerpt from the book: Walking Out, Speaking Up: Feminist Street Theatre In India

The late 1970s saw the rise of feminist street theatre in India, powerful plays spun around themes of dowry killings, sexual violence and everyday misogyny. Often based on real events, they travelled to colleges, neighbourhood parks, and even gallis of colonies which witnessed them. In her recently launched book, Walking Out, Speaking Up: Feminist Street Theatre In India, political scientist Deepti Priya Mehrotra looks back at these years when feminist networks used theatre as a strong, impactful means of mobilisation. Here are some edited excerpts from the book published by Zubaan:

Collective Theatrical Production: Delhi, 1979

Stree Sangharsh, a feminist collective, was formed in Delhi in 1977 by a small group of academics and activists. They were among the first to expose and denounce dowry deaths as being, in fact, murders. Other women’s organisations, Mahila Dakshata Samiti (MDS) and Nari Raksha Samiti, also challenged the routine dismissal of such deaths as accidents. Soon after the first protest demonstrations in mid-1979, Stree Sangharsh initiated the making of a street play on bride-burning/dowry murder. The aim was to reach wider spectrums of society, so that there may be a collective recognition of abuse and violence, pervasive within many families. Such awareness, they felt, was a necessary step in what would be a long battle for ending violence against women.

Stree Sangharsh had an extraordinary set of thinkers, active in workers’, human rights and peace movements: including Radha Kumar, Amrita Chhachhi, Gita Sahgal, Urvashi Butalia, Ayesha Heble, Subhadra Butalia, Gouri Choudhury, Bharati Roy Chowdhury and a few others.

Making Om Swaha: The Process and the Participants

Realising how relevant creative media was for effective communication, Stree Sangharsh members thought of making a street play. They invited two young, sensitive theatre-persons, Anuradha Kapur and Maya Rao, who agreed to script and direct a street play. Both of them were part of Theatre Union, a recently founded group for innovative, radical theatre.

Stree Sangharsh invited many more people concerned with women’s issues to participate in the process of devising a play. Thus, Om Swaha was developed by a fluid collective, including activists Amiya Rao, Renuka Mishra, Primila Lewis, Manmohan Dayal, Rukmini Rao, Kalpana Mehta, university teachers Sudesh Vaid, Kumkum Sangari, Pankaj Butalia, and others. Regular intensive meetings were held, debating and discussing the story, characters and plot. Maya and Anuradha participated in each meeting and, on the basis of the discussions therein, would later write up a drama sequence. At the next meeting they would present the sequence to the group, absorb the group’s responses, and proceed to rewrite the script on the basis of collective feedback. It was a very unique collaborative process. They drew on real events to build the plot: the script they evolved had elements from the life-and-death of, in particular, Hardeep Kaur, Tarvinder Kaur, and Kanchan Chopra.

Hardeep’s story in Om Swaha closely followed that of the real Hardeep Kaur, while Kanchan’s was an amalgam of Tarvinder Kaur and Kanchan Chopra’s stories. The script altered details, fictionalised for dramatic flow, depth and impact. Events were imaginatively reconfigured, transmuted into public spectacle, to inspire reflection and critical thinking. However, the original version of Om Swaha was faithful to reality in showing that both Hardeep and Kanchan were killed by their respective in-laws. (It was in the second version that Kanchan’s story was further fictionalised, showing her making an active choice to survive, even if it meant walking out of her marital family.)

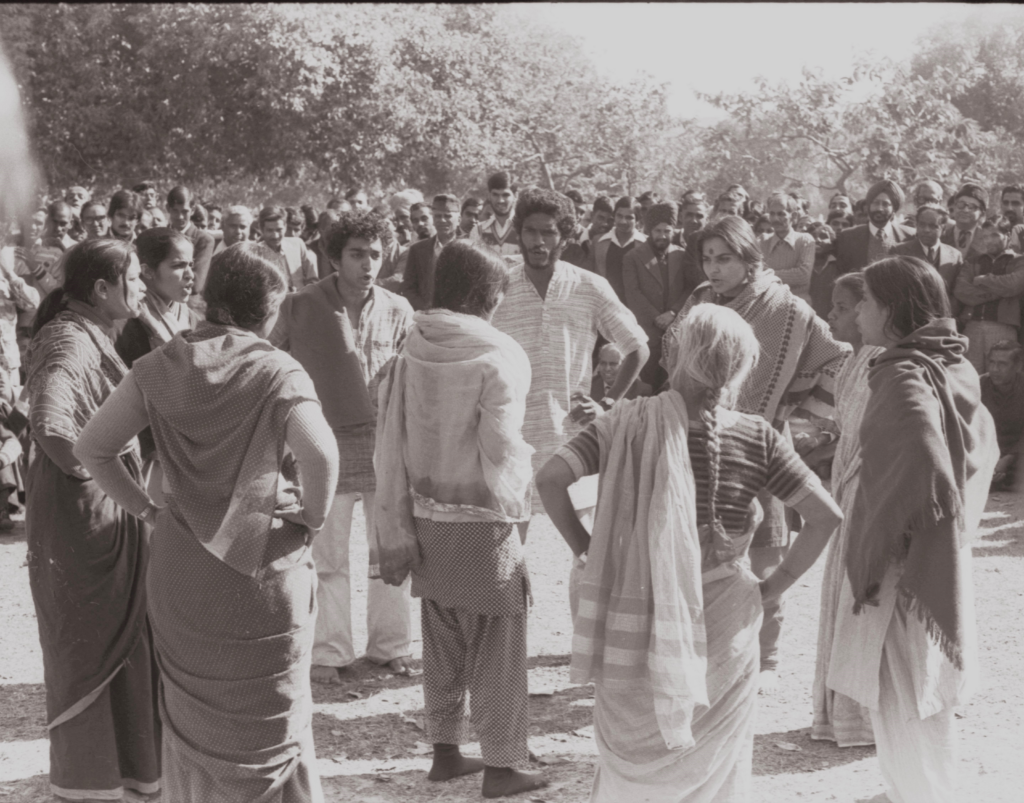

Once the script was ready, Anuradha and Maya held workshops, training the activists to act. There were no professional actors available for this venture, so willy-nilly the members of Stree Sangharsh and some others became actors. They threw themselves into the task at hand; rehearsals took place in earnest and within a couple of months, the play was ready!

Subhadra: ‘We Have to Do Something!’

At the time, Subhadra Butalia was teaching at Dayal Singh College, Delhi University, and lived with her family in Jangpura. Across the road was a big house where a joint family of industrialists lived; Hardeep Kaur was the daughter-in-law.

I shall never forget the afternoon Hardeep Kaur was set on fire. I came out on to the small balcony of our house shortly after lunch. I registered smoke coming out of Hardeep Kaur’s house. Suddenly, her screams rent the air. The husband and wife often had noisy arguments and confrontations which, as neighbours, we ignored. But this was different. The girl was burning, screaming, and people from houses around rushed out. It was as if we were all paralysed, still standing and staring when a taxi drew up in front of the house and Hardeep was brought out, wrapped in a white sheet. She needed support to make it to the taxi and was rushed off to hospital. The neighbours who had collected in small groups to talk gradually dispersed and quietly filed back to their homes (Subhadra Butalia).

Hardeep sustained 70 per cent burns, and died within two weeks, on 2 November ‘78. She gave a dying declaration, in the presence of a magistrate, stating that she was burned by her mother-in-law and grandmother-in-law. Meanwhile, the neighbourhood seemed indifferent, and the general opinion was: it’s best not to interfere in domestic affairs.

However, Mahila Dakshata Samiti began to investigate the death. Two women from MDS came to Subhadra Butalia’s house, to enquire if she knew anything; they also asked other people in the neighbourhood. Perhaps under pressure from them, the police began an investigation. On the basis of Hardeep’s dying statement, a charge-sheet was filed and the case was sent to court. Most neighbours told the police they saw and knew nothing. Only Subhadra Butalia testified, describing what she had seen.

Even Hardeep’s brother was unwilling to testify against her marital family. He said that Hardeep was gone anyway; he needed to look after his own family, and his business. If he kept chasing the case, all that would fall by the wayside. The talk was that Hardeep’s in-laws had paid him off. They did certainly bribe people in the neighbourhood. Hardeep’s father-in-law actually visited the Butalias and offered to gift Subhadra any item of her choice from his shop, if she were to retract the statement she had made in court. She refused, of course. Members of Hardeep’s marital family were convicted of the crime. The family promptly filed an appeal in the High Court, and deployed a common trick: the mother-in-law and grandmother-in-law were admitted to hospital, claiming they were ill.

Subhadra Butalia writes, ‘The more I tried to get Hardeep out of my system, the more her story clutched at my heart […] At some stage, those of us who were getting more and more worked up about these incidents began to think we could not just sit around feeling angry. We had to try and intervene in some way.’

It was soon after Tarvinder Kaur’s death that Stree Sangharsh organised the first-ever anti-dowry-death demonstration, on 1 June 1979, in Model Town. The protest was far more successful than they had anticipated, with people responding spontaneously, and appreciative media coverage. This inspired their decision to build up an intensive public campaign. They had already observed how the poster exhibition created a stir wherever it was put on. During discussion, the idea of a street play came up and there was tremendous excitement, for they thought a play had great potential. But none of them knew how to make a play:

So we got in touch with a friend, Anuradha Kapur, and she brought in another friend, Maya Rao. Anuradha and Maya scripted the play we eventually put up on the basis of real-life stories of dowry deaths that we told them and those they were familiar with, and we began rehearsals in the house of another friend, Lakshmi Rao, in central Delhi.

We would assemble there every day, travelling across the city by bus or scooter riksha—none of us was rich enough to take taxis and few of us had cars. Anuradha and Maya would take us through a series of improvisations on the stories we had told them, and bit by bit a final script began to take shape. We were all dedicated and fully committed—I think none of us even felt the tiredness of travel or of the long hours we spent discussing, enacting and writing this or that scene. As I look back on that period today, I wonder how I managed with my job and my household responsibilities and all the time taken for travel. It seemed that in no time—though in reality I know it was at least a month or two—we had our play ready. We called it Om Swaha (Subhadra Butalia).

Maya: ‘Thinking Up Dialogues, Making Up Songs’

Maya Rao, the well-known and exceptionally talented theatre-person, recalls the process of scripting Om Swaha, and directing and acting in it:

It Came Together, and Continued to Grow

It came together: content and form. Home, neighbourhood, events, and emotions were evoked through familiar sounds, images and actions—the morning rush of breakfast and tiffin boxes, marriage rituals conveying absurdly harsh injunctions, a two-wheeler dowry demand vrooming in so that the wedding nuptials could continue; abuse, murder, the disposal of the corpse, All India Radio announcing another death… Yet, soon, one more woman is married off, into a similar household.

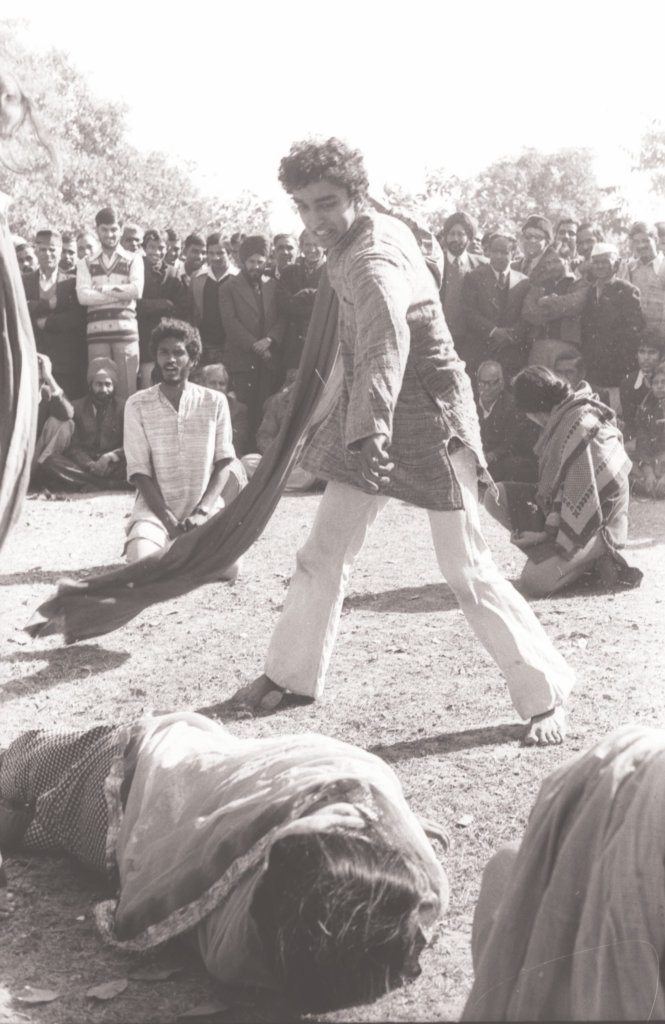

The structure was set by Maya and Anuradha, but they encouraged the actors to innovate. While improvising the wedding scene, somebody began singing ‘Kala Doriya’, the popular Punjabi wedding song, and it stuck because it was so appropriate. When the bride was to leave for her sasural, Subhadra started singing the heart-wrenching film number, ‘Babul ki duayein leti jaa’, and it too became a permanent fixture. Similarly, after the wedding and early-morning household scenes, when her in-laws berate Hardeep, somebody picked up a dupatta, and the directors felt, let’s use this. Thereafter an orange dupatta, or else shawl, was essential to every performance of Om Swaha, to collectively flail and flog Hardeep, and then simulate flames, rising and engulfing her.

In 1979, I was teaching political science in Kamala Nehru College, but most of my time was spent doing theatre with the girls. Then Anu and I got a call from someone in Stree Sangharsh, saying, there are all these dowry deaths coming to the fore, and some of us want to find a way to start a public discussion around this—so will you do a street play?

At that point, we didn’t have any actors. It was probably a blessing in disguise, because we told them, ‘We don’t have any actors. If you people will act, we can think of doing it!’

None of them were actors, but all of them were activists, and thereby hangs a tale. We spent evenings and evenings together at meetings. There were many women, each differed from the other in terms of ideology, politics, personal tendencies, everything. It was a great learning curve for me. When you’re in it you want to tear your hair out, because you can’t get a sequence, you can’t get one-tenth of a sequence, because already there are ten opinions before you can even design the play!

We would say—now we’ve got all these views, now we’re going off to write some sequences. We did a bit of writing, but then of course we had to go back and open it for everybody. There was all this going to and fro. We would make blocks and the dialogues, and take it back to them, and they’d say, ‘No, how can it be like this?’ There was a lot of all that!

Anu and I kept thinking up words and dialogues. We’re hopping in and out of three-wheelers, and making up songs. That’s how we made ‘Na das lakh, na teen lakh, na ek lakh, na ye na vo, karoon main kya…’43— it was made in a three-wheeler! This was the song chanted while killing Hardeep, and it was incredibly powerful. It became popular and quite famous. We’d sit in Anu’s house or mine, and keep perfecting the songs. We felt top of the pops, what fabulous lines we’re creating, when we made a song, and it all fell into rhythm. After thirty years, people still remember some of those lines!

Then we held workshops, regular actors’ workshops, especially for activists. Acting is not just about talking and giving a speech, it’s about using your body. And we were doing street theatre, which is about using all of your body! It was great fun, and it was all kinds of things.

The meetings and rehearsals were held in different people’s homes. There would be hangers-on, some people who’d just sit and watch us rehearse, discuss and chat. There was a core of people, but there were these others too, a floating population. One day you think they’re doing a role, but the next day they’re not there!

Anu and I thought we’d be directing, but found ourselves doing roles too. I acted as Hardeep, and at some point I acted as Kanchan. Apart from Anu and me, the initial cast were all activists. At some point a number of boys joined, Vinod Dua, Manohar Khushalani from Theatre Union. People would come, do a show or two and move on. It touched various people and they touched the play—it was like that.

A Hundred Shows In One Year

The very first performance of Om Swaha was at Indraprastha (IP), Delhi’s oldest women’s college. It was held in the expansive open space in front of IP’s graceful and stately main building in Civil Lines, a stone’s throw from Delhi University’s main campus. It was late 1979. The IP College Women’s Committee, which had been formed in 1978, invited the group to perform.

A few hundred college girls gathered around, and were amused by the sutradhar’s opening spiel: ‘Namaskar, Sat Sri Akal, Walekum Salaam, Welcome, Hello, Hi! Come, you will find what you want! I am Professor Shetty M.B.—Marriage Broker! I have IAS boys, right up to peons. Unemployed boys demand just Rs. 2 lakh as dowry, to open factories after marriage. Doctor, engineer, businessman, officer, professor, clerk, I have boys AtoZ. Girls, fathers, brothers of girls, bring your cash, pick a groom! The girl must be fair, good-looking, pleasant and caring. If she is a working girl, a 2 to 10 percent special discount is available!’

A radio announcement changed the mood to sombre: ‘Hardeep Kaur, 20, wife of Gurpal Singh, was admitted to Jayprakash Narayan Hospital with severe burns. She died on 2 November 1978.’ Her neighbours say they saw nothing.

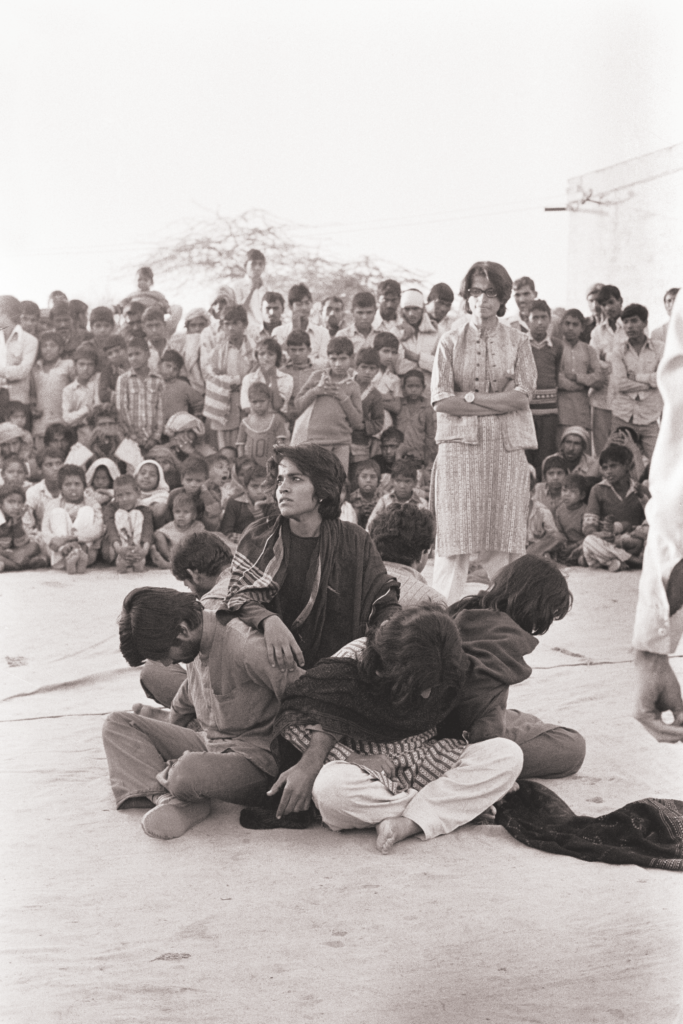

Then her friend, Kanchan, shares, ‘After marriage, whenever I met her, she wept. Her in-laws tortured her for dowry! She has been killed!’ The young women in the audience were tense by now; their own dreams of marriage mixed with dread as they watched Hardeep’s story in flashbacks. Women sang ‘Kala doriya’, the bride and groom were about to circumambulate the sacred fire, but the groom’s father shouted, ‘Stop the wedding! Where is the scooter you promised?!’ The chorus appealed, ‘Don’t stop the wedding! The girl’s life will be ruined,’ and a two-wheeler, mimicked by two actors, arrived. The pandit chanted verses, a satire on the routine rites: Om Swaha! Om Govindayanam, Om Gopalayanam, Om Scooterayanam! Beti, worship your husband, be suhagan forever! Whether or not he is Ram, you will be Sita… Even if he insults your parents, you must serve his! Let them mould you as they want, like wet clay!’ The chorus sings, ‘Babul ki duayein leti ja, jaa tujhko sukhi sansar miley…’

Rather than the happy future she wished for, Hardeep frantically cooks, cleans and serves, yet is constantly harassed by her husband and in-laws. Their complaints built up and morphed into something sinister as they closed in around her, chanting:

‘Na das lakh na teen lakh na ek lakh, no fridge no TV, no press no mixie, ha ha ha ha.

No ear-ring no bangle, no toe-ring no nose-ring, no shoes for sasur, No suit for brother, no jersey for Pappu, no sari for nanad, ha ha ha ha…

No this, no that, got nothing, what do I do? Ha ha ha ha, Hah, ha hah ha, hah ha, hah ha, ha ha ha hah hah hah hah hah haaaa…!’

Frenzied voices built into a crescendo as her in-laws battered and finally burnt Hardeep.

No action was taken against Hardeep’s killers. And soon, Kanchan was forced into marriage, and similarly abused by her in-laws: ‘I, Kanchan, am still alive, but everyday a new demand, insults, taunts, and beating.’ Kanchan’s parents insisted she try to adjust in her sasural; the sutradhar said: ‘Kanchan, what can you do all alone? This has been going on since centuries… At least you did not keep quiet. You tried to fight your battle.’

The play closed with a helpless Kanchan screaming: ‘Yet my situation hasn’t changed! So long as people keep giving dowry, taking dowry, we women will keep on suffering! I have expressed my feelings, but what has everybody been doing? Simply watching the fun?’ The chorus exhorted the audience:

‘Na dahej lena, na dahej dena… Do not take dowry, do not give dowry!’

The audience was pensive; the play affected them powerfully. Shettyji recalls, ‘People in the audience had tears in their eyes when they heard Babul ki duayein, sung beautifully. Even we would get goose-pimples!’. Subhadra Butalia recalls: ‘…As Maya’s screams rent the air, it was almost as if everything, even the traffic on the roads outside, came to a standstill. Even we, who were familiar with every line and nuance of the play, were moved.’

For the actors, the first show was reassuring. They had rehearsed often, but didn’t know how audiences would respond. Students spoke frankly during the post-performance discussion, as was the case in other women’s colleges too. Questions and contradictions seemed to sharpen within their minds. Seeds were sown, some of which would likely take root and grow over time. It was, for some, an introduction to feminism as a way to engage with the conditions of one’s life, and take courageous action.

The group also performed in mixed colleges, such as the Delhi College of Vocational Studies (DCVS). It made a huge impact there. Students got inspired and three college boys joined the group, becoming part of the chorus for a few shows. Sheba Chhachhi, freshly returned to Delhi from the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, vividly remembers seeing the performance at DCVS: ‘I’d heard so much about the play, so I went along. I stood there watching it, feeling tremors run through my body. I was really very powerfully affected by that performance. I can still feel it—a sudden flash of Om Swaha!’

There were hostile responses too. Maya distinctly remembers performing at a mixed college, either Venkateshwar or Deshbandhu, which had only a tiny percentage of girls. The actors made a circle with dupattas, to mark the performance space, but some boys crossed the circle and kept coming closer, in a threatening sort of way: ‘In the end we had a space not more than four feet in diameter. It became a contest: “Will you have the last word, or will we?” As we did the last line, we picked up our props, made a beeline for the van, and left. It was all very exciting!’

What did you think of this excerpt? We would love to hear your thoughts, suggestions, and experiences. Write to us at contact@behanbox.com.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.