‘Our Work Went From Local to Global – That Is ASHA Workers’ Biggest Milestone’

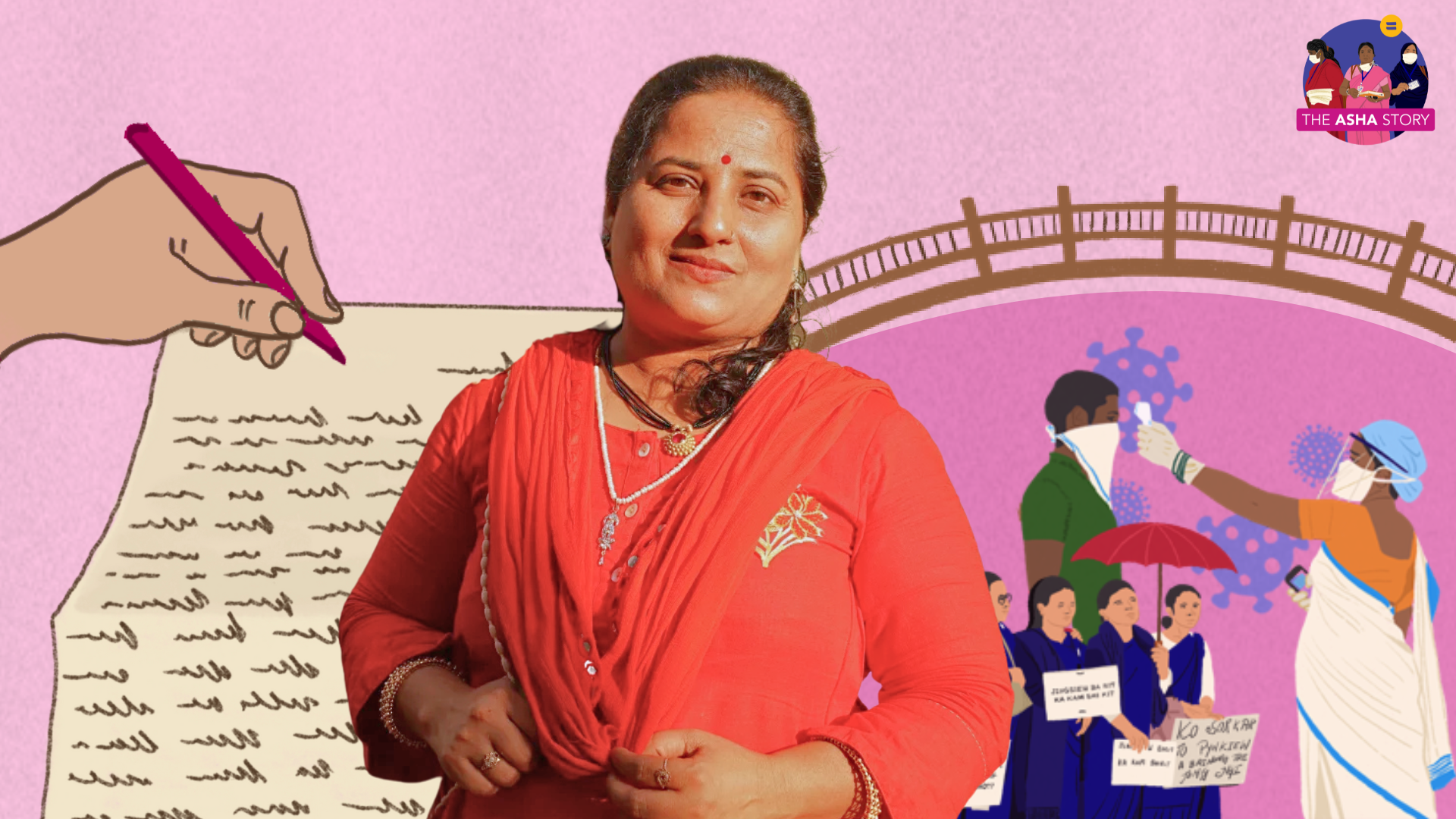

Netradipa, an ASHA worker and union leader from Kolhapur, Maharashtra, recalls stories of how she has gone beyond the call of duty and become a friendly face of a distant health system

We are documenting ASHA workers’ voices in an effort to build a ground up oral history of the ASHA programme for ‘The ASHA Story’ — our public archive of ASHA work and workers in India.

Where does work end, and where does care start? For Netradipa, an ASHA worker and union leader from Kolhapur, Maharashtra, the lines blur with ease. She recalls for BehanBox stories of how she has gone beyond the call of duty to help girls, women, single mothers, and families, the friendly face of a distant health system. Her journey started in 2009, and along the way, she has discovered the roots of community health initiatives and the gendered politics of caregiving. These histories shape her ‘work’ today.

How did you learn about the ASHA programme?

My mother, who lived in Sangli (50 km north of Kolhapur), bought newspapers every morning and one day, she showed me an ad from the National Rural Health Mission. They were recruiting women to be ‘ASHA swamsevika’, and anyone who had good communication skills, was interested in social work, was amiable and friendly, and lived in that locality was encouraged to apply. I had passed 10th grade but wasn’t working; I used to take tuitions in the neighbourhood. My mother said it would be a good opportunity to work with the health department. I was 35 years old and my two children had grown up by that time, so I wasn’t worried about who would look after them.

I was always interested in health, and wanted to be a gynaecologist. But I was married off when I was 16, immediately after passing from 10th, and there was no time or opportunity to continue further education. I completed a part time course in economics. Shaadi ke baad sab badal jaata hain, ghar parivar sabki zimmedari lekar main science mein admission lene ka sapna pura nahi kar sakti thi. Since I was already interested in health and social work and liked to socialise, I applied and was confident that I’ll do a good job. We submitted our documents to the gram panchayat and were selected there; the Taluka Health Officer put out an order announcing the names.

I assumed there would be a salary but found out much later there is no salary and this is incentive-based work. Theek hai, I thought, kaam accha tha. Logo se mil julke baat kar sakte the, unke behaviour mein badlav lana, counselling karna, I enjoyed this work so I continued it. Later I joined the union in 2011 and eventually became a union leader – protesting for ASHA workers’ welfare – and that role deepened this ‘job’.

At the time, what did you make of the distinction between an ‘employee’ and ‘volunteer’?

I didn’t think much of it because in general, ASHAs’ position at the time had no value in the eyes of the community or government. They weren’t rigid with their selection criteria — the minimum requirement was anywhere between 7th – 10th grade; in tribal areas such as Gadchiroli even women who had cleared 5th grade were picked. The government was more concerned that the women should be rooted in the community and be able to talk to others, and accompany people to the hospital.

Most women had to drop out from school and realised they wouldn’t get a proper job with this level of education. At least, we thought, this is a role akin to a government job and eventually we would get a permanent position. That was the incentive for many ASHA workers to stay.

I also stayed because of my union work. If we have to fight for ASHA workers’ rights and justice, I will have to do more and be more. I’m still an ASHA worker but also a union leader; I keep track of the nature of work, what changes we need, reports and metrics tracking how ASHA workers have changed the system.

What was work like in the early years?

There wasn’t much work then – we had some 12-15 indicators, like doing immunisation for children, conducting Gram Poshan meetings, or doing surveys. I also work in an ‘open area’ where people from more well-to-do families lived and these were generally a little resistant to health communication. No one wanted to work there.

Initially there was little cooperation from families when we went from home to home – yeh kaun information lene aayi hai, kyun aai hai, yeh kya nayi medicine hai (who is she, why does she want information, what is this medicine) – people didn’t respond, or were rude and left me standing at the door. They thought we were salesmen. It pinched and I wondered why they reacted this way considering we’re there to check on their health. It took us two years to get them to trust us.

It was only during Corona-kaal when things changed. Earlier we used to attend to women and children, and whenever we visited, men were usually not home. But in 2020 since everyone was locked inside their homes, it began to be known and recognised that we lived in and worked for the community.

In 2018, I remember visiting the home of a single Muslim woman. She had lost all her family members and showed suicidal tendencies. She lay on the floor of her home and was running a high fever. There was a rank smell in the house, and no one – not even her relatives or the health department – would agree to visit her. She was scared to go to the dawa khana (dispensary). It took four visits for her to start trusting me and agree to visit the health centre. Her blood tests showed nothing abnormal but because she had mental health issues, we took her to a psychologist and she was given medicines. I would go every day to her house after that with food, something different for breakfast and lunch every day. I fed her when she refused to eat. It took her two years to recover – now she can cook for herself, look after herself. I check in every now and then and monitor if she’s taking her medicines on time. I believe that jo bhi karna hai, theek se karna hai (one should always do one’s best).

Some cases stay with you but there is an entire record of our work in our diaries – where I went, who I met, people’s condition, and the course of action.

Did you have any support systems to deal with the early trust deficit?

It took a lot of time. One time, we were rudely asked to leave a house we were visiting to collect information. I wanted to cry; out of shame I returned home. Later the government provided us with a medicine kit including paracetamol and other basic medicines. When people started seeing the effects of taking medicines regularly, they slowly accepted that sarkaari dawa is not bad for them. They would ask if we would accompany them to the centre: Aap hongi vaha? Aap aayengi humare saath? (will you be there)? It still happens.

Earlier people were afraid of going to the hospitals; in my area they thought they would die if they took sarkaari davaiyan or that no one would attend to them at local health centres. It was challenging and even when we managed to convince them to visit a health facility, they would come back disappointed either due to the shortage of drugs or staff shortage. Yeh beech ka safar bahut mushkil tha (it was a hard journey).

When I spoke to the Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM) in our area about how often people were rude to us she comforted me. They had done surveys long enough to tell us that this hostility was normal, and it would go away once people got to know us and our work. She said: ASHA ka kaam is sarkaari kaam, health ka kaam, samaajik kaam — accha kaam — and I should stay. She guided me when I needed help. Once, in a home where a child had hypothermia, I wasn’t sure if the baby should be taken to the hospital or if the mother could be trained to keep her warm. I called the ANM and her questions helped me observe the case more carefully and come to a decision. I noticed the mother was feeding the male baby more than the female one, and the girl’s hypothermia was getting worse. I decided to take her to the health centre. In times of confusion I have also used the Sarathi 104 helpline a lot for guidance in times like these.

The ANM and I are still in touch. She never pressured us or demanded that we immediately showed up to submit a document. She was even supportive of my work as a union leader. I wouldn’t have lasted if she were like other officials today – rude, unaccommodating, brusque.

In the early years, what was it like doing this work as a woman – going door to door, entering people’s homes, conducting surveys?

Even though I am educated, I was still nervous. It is one thing to go out for a job, and another to go from home to home, collecting personal data. With family planning surveys, we felt very uncomfortable talking about Nirodh (condoms) or garbhapaat (abortion). People themselves didn’t expect a woman from the outside to come educate them, and we ourselves didn’t know this is what the job involved. No one, before the ASHA programme, had done this. The work of Anganwadi workers was far less intrusive.

In the beginning, we struggled to deliver yojanas to people. I kept wondering – what kind of a job is this, without salary, without respect, without cooperation from people, what is the point of continuing? Also we were earning a pittance at the time – who would want to work for about Rs 200-300 per month? ASHA coordinators and ANMs were inundated with complaints at the time from ASHA workers, and many left. Even the ANMs struggled to keep us motivated. They would keep us going with promises of future programmes, better incentives, acche din.

And what was your relationship like with the women in the community?

Women have a different relationship with ASHA workers. When we walk into a neighbourhood, young girls see us and run to the homes, excitedly telling their mothers ASHA didi is coming. Kya le kar aai ho? (what have you brought today?) they would ask.

One of the challenges was getting newly married women to open up. They were often hesitant to speak freely in front of their mothers-in-law. We had to build a relationship with both – the mother-in-law and the daughter-in-law. If they were sitting together in a room, the mother-in-law would usually dominate the conversation. The young bride would only speak up when she had some privacy.

Later, we received training in how to communicate more effectively – how to read their body language, how to sense whether they were doing well or needed support. Over time, they started opening up. Some took my number to call or message privately – sometimes about health, sometimes about other issues. They didn’t feel comfortable sharing things with their husband or even their maternal family, but with us, ASHAs, they felt they had a trusted friend who could guide them. Now, we’ve built real friendships with both the women and their mothers-in-law.

I’ve made many friends this way. Earlier, we’d spend just five minutes at home; now it takes at least half an hour. People invite us in for chai or naashta, and everyone has questions—about themselves, about their children.

We also started with a common WhatsApp group for the community, first with both men and women, but created separate groups later (this was after one man sent inappropriate messages to a woman). My WhatsApp status updates are related to health, which women say they rely on. But since those updates disappear after 24 hours, the women themselves asked for a separate group. They were thrilled – sirf mahila ka group, khulke baat kar sakte hain.

Can you tell us more about the caste dynamics within the ASHA programme?

In my region, most ASHAs – 15 out of 24 – are from middle- and lower- caste groups. We have been trained to offer care irrespective of caste or religion. Some ASHA workers from marginalised castes, working in regions dominated by upper caste residents, struggle to form bonds and a pehechaan in the community. This distance has been reduced since Corona. Now people know every ASHA didi is working for our health, and is a symbol of welfare, and are relatively more welcoming. This consciousness has built over time, lekin logo ke dimaag se abhi bhi jaat nahi gayi hain (people are still very caste conscious).

ASHAs run a ‘triple shift’ – inside the house, in the community, and with the health system. Did this care work ever felt like a burden to you?

Not till Corona kaal. “Everyone is inside and you are going outside,” my family would say. We don’t have big houses, it wasn’t possible to isolate. ASHA workers also have children, a family, and everyone was scared. Bahut tanaav aata tha ghar ki taraf se (it was a tense time at home). I was scared. What if something happened to us? Worse, what if we brought something back and our families got sick because of us? That burden of care, I felt that every day, but we couldn’t leave – this is seva, we can save so many lives with our work. We tried to reassure our families, promising we would be careful. We used sanitisers, wore masks, and as soon as we came home, we would disinfect everything – our pens, diaries – and go straight to the washroom before touching anything else. By then, we had seen and learned enough about how to protect ourselves and our families.

Before Corona, they didn’t say much because they didn’t fully understand the nature of our work. But [even then] there was a fear inside of us. Visiting TB patients, for instance, was seen as a risk, and at that time, we didn’t even have masks or protective gear. We were visiting and talking to many people every day without knowing who might be sick. ANMs advised us how to safely collect information from patients: Aage jaa kar baat nahi karni hai, don’t get too close, safe jagah baithna hai, find a safe place to sit and talk. We followed that advice. What came to be known as “social distancing” during the pandemic, we were already trying to practise in our own way.

You joined the local union in 2011. How did you become a part of the protests?

There were three organisations in the area – one was the Centre of India Trade Union and the other two were local unions. In 2011, one of the local unions approached me and for the first two years, I was just a member. It was through them I began to understand the larger landscape of ASHA workers — the number of women out there doing the same work I was doing in Kolhapur. They shared books and stories, and I realised that if we wanted our rights, we would have to fight for it.

I started meeting ASHA workers in other tehsils and taluks, and learned about their challenges. I was also in touch with doctors and social activists. Around 2012-13, I met Kavita Bhatia who was doing a PhD on ASHA workers and collaborating with us at an all -India level. She asked detailed questions for her research about our work – about unpaid labour, long working hours, the challenges we face. She influenced my knowledge and thinking around our work. She took this to a global level, added me to health groups, and through those platforms, I got the opportunity to participate in discussions and write about our experiences. Together, we did a global presentation on the role of ASHA workers – how we influenced behaviour change in communities, the health impact of our work, and the potential we have to drive meaningful change.

Kavita also told me about the Gadchiroli experiment (a community health programme in the Nineties pioneered by Dr Abhay and Rani Bang, where they trained women to provide neonatal and reproductive care within homes). Women had the capability to learn, be empathetic agents of change and when trained, could make a real impact on child healthcare. There was a newspaper article about how their work reduced the infant mortality rate. I was deeply inspired. What could be more important, more meaningful, than saving a life? In our society, we’re conditioned to believe that caring for children or others is women’s work. And yes, women are often more patient, more empathetic, maybe that’s why women are chosen to be ASHA workers. But it’s also about how women speak, how they listen.

I don’t know what is and should be called ‘women’s work’, but numbers will tell you that we have fulfilled the original goals of the ASHA programme.

How do you find time for rest and self care? Is there something you wish you could do more often when time allows?

I try to take out one hour for myself – for meditation or pranayama. I realise I’m not as energetic as I was years ago. So I began reading more about how to stay fit after 40. We go around advising others about what to eat and what’s good for their health, but no one really tells us what’s good for older women.

I began studying on my own, watching videos on YouTube to understand what my routine and nutrition should look like, what supplements I should take, and when. After 40, many women stop paying attention to their own health. Their pain is often dismissed or normalised as “common,” but it’s not. Earlier, I didn’t know how to guide women above 40 but now I talk to them specifically. I collect women from 4-5 houses at a time and talk to them. A woman called me the other day to say she felt proud that someone like me, who cares and looks after people, is in her neighbourhood and is her friend. Voh madam ache-ache status rakhti hain, information milti hain. Creating this awareness and behaviour change is our work.

The day is packed, but I don’t mind. If we’re doing a good thing and see that satisfaction in people’s lives – that smile on women’s faces – we forget our exhaustion.

What are the major milestones in your journey? What gives ‘dignity’ to your work?

I went from being a local ASHA to a global ASHA worker – this is the biggest milestone. What I do in a village, my thinking, and my work, has reached international platforms. I see so much change in myself. I used to be quiet and hesitant, thinking twice about going somewhere or speaking up, now I’m bindaas with what I say and how I say it. Haq se baat kar sakte hain logo se.

It is one thing to do a job, but to stay in a community, bring change in people’s behaviours and thinking, and through that learn so much, this is challenging but also life- giving. It feels easy now – there is WhatsApp, Instagram, groups to share information – and we’ve been able to use social media to reach more people. We have done so much work, we have so many stories. An area is like a family to me, and today I have 200 families – and I have responsibilities towards them. They should be healthy, which inspires me to keep trying.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.