Why Indian Election Campaigns Will Talk About Menstruation But Not Marital Rape

Sexual and reproductive rights of women do feature in the election agenda of political parties but only those that do not defy established social norms

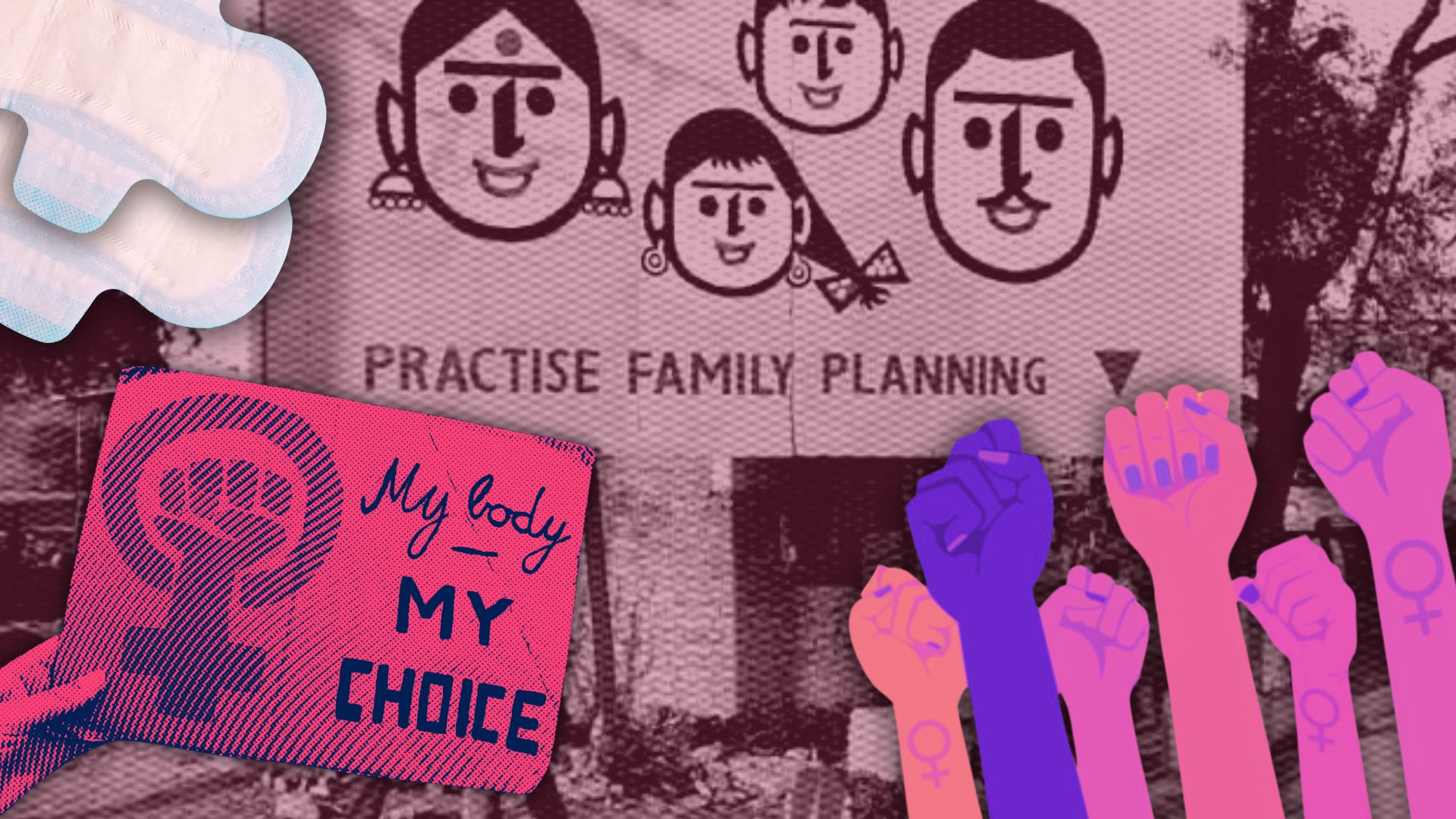

In their poll agendas, India’s political parties are selective about the sexual and reproductive health issues they back: their concern is the family, not the individual, and they choose to focus on women’s role as mothers and upholders of “honour”, and not their agency or right to choice, say gender experts and activists.

Recent global election campaigns have mirrored this approach as the question of the right to abortion roiled many countries across the world (here, here and here) and actually decided critical election choices in the US. This year, politicians across the world dabbled in pronatalist rhetoric while blaming “childless cat ladies” for declining fertility rates.

However, the discourse in India is moulded by its legislative history, population control measures and patriarchal attitudes, experts told BehanBox.

In recent elections, manifestos have promised changes ranging from menstrual health services to laws regulating marriage. But issues that disrupt hegemonies of caste and power, such as marital rape, forced sterilisation procedures, and gender-affirmative care, rarely figure in this imagination.

“Women are put on a pedestal and seen as goddesses, but not as humans with gendered sexual and reproductive health needs in political discourses across spectrum, states, and parties,” says Sonal Kapoor, founder of Protsahan, a Delhi-based NGO working on gender justice and access to healthcare.

Sexual and reproductive health rights include but are not limited to: bodily autonomy; access to knowledge and healthcare to avoid unintended pregnancies or sexually transmitted infections; gender-affirming care; voluntary and non-coercive reproductive services; and the freedom to decide sexual partners within and outside marriage. Almost 197 governments have formally recognised the right to sexual and reproductive health free from coercion, discrimination, and violence.

In recent state and national elections, Indian parties have been wooing a rising female electorate with promises of ‘nari shakti’ or women power. In 2014, Narendra Modi in his first address as Prime Minister condemned rape, female foeticide, and appealed to “parents to stop their sons before they take the wrong path”. Ten years later, BJP’s 2024 manifesto promised to expand its flagship Jan Aushadhi Suvidha Sanitary Napkin scheme that offers sanitary pads at one rupee. Congress’s Nyay Patra spoke of safe and hygienic public toilets. Implementation of legislations to prohibit child marriage and laws like the Uniform Civil Code to regulate marriage and adoption issues have been pitched stridently.

This gender-centric ballot push is driven by a demographic shift in India. Parties introducing the issue on the ballot are “speaking to a significantly younger country, from the 1950s to now”, explains Ramya Kudekallu, an assistant professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law in New York.

Almost 20% of India’s voters are aged between 20 and 29 years. Moreover, women voters continue to outnumber men: almost 26.6 crore women exercised their right to vote in the 2014 elections, and in 16 out of 29 states, more women voted than men. This year, almost 31 crore women cast their vote.

Despite their electoral clout, Indian women face constant health challenges: 7% of deaths of women in the 15-29 years age bracket occurred due to issues relating to pregnancy or childbirth as of 2020. Between 2007 and 2015, unsafe abortions were responsible for 5% of maternal deaths. Female sterilisation is still the most common modern contraceptive method used by women. Almost half of all girls in India marry before they turn 18.

A young electorate in its reproductive age, Ramya notes, is “invested in these ideas of autonomy, access to health care… equity and the ability to participate or consent to intimate relationships–all without the trappings of patriarchy or cultural overrides like sexual purity or virginity”.

Sonal concurs that there is political capital in speaking about ‘taboo’ subjects like menstruation. “There is nothing left, right, or center about women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights; it’s plain common sense for winning the confidence of women voters.”

‘A Narrow Interpretation’

While menstrual health and female foeticide are important issues, Indian parties have used them to make “piecemeal” promises and theirs is a “narrow” recognition of sexual and reproductive rights, said this 2021 essay in The Hindu. This dilutes the recognition of sexual and reproductive health issues as a ‘right’ people can demand of their elected leaders, and also disregards the right to bodily autonomy, it argued.

During a slum panchayat charcha (discussion) with migrant clusters in Delhi, a woman told Sonal: “Sarak aur bijli banwane ka toh waada sabhi aadmi karte hain, par prasav ke doran maa ke marne ya bachcha mara hone ka toh kissi ko farq hi nahi padta (everyone promises roads and electricity, but no one cares if a mother or child dies during childbirth).”

Issues that figure in the electoral discourse tend to be those that “can be discussed without challenging the patriarchal foundations too directly”, Sonal says, pointing to family planning and menstruation as examples.

This is not the the case with say the stance of Indian parties on criminalising marital rape. Forced intercourse within marriage violates sexual consent and deprives a woman of the right to make reproductive choices, and negotiate safe sex practices. It also discounts the danger of sexually transmitted diseases and increases the likelihood of unintended pregnancies and subsequently unsafe abortions. But the issue has never found space on the ballot in India, says Ramya. The CPI(M) is the only outlier on this.

Moreover, sexual and reproductive rights are framed only in the context of women, she adds, neglecting men’s right to bodily autonomy and ignoring trans individuals with gender-affirming healthcare needs and those within the LGBTIQ+ community at large.

In 2019, a network of NGOs working on enabling women’s access to healthcare called for political parties and election manifestos of parties “to demonstrate political will and commitment to safeguarding women’s health and rights”.

Early Legal Reform

Unlike the US, issues such as contraception, abortion rights and maternity leave are not viewed as unmet promises by the electorate or government because they have been to a degree resolved in the Indian context through the legislative route, argues Ramya.

India legislated early on the access to contraceptives with the KS Puttaswamy judgement (2012) that recognised women’s constitutional right to make reproductive choices and the Suchita Srivastava & anr v/s Chandigarh Administration (2009) order in which the Supreme Court observed that women’s “reproductive choices can be exercised to procreate as well as to abstain from procreating”, which is central to respecting their “right to privacy, dignity and bodily integrity”.

Similarly, India legalised medical termination of pregnancy in the 1970s with the Medical Termination of Pregnancy (MTP) Act, 1971, amending it twice – once in 2021 to raise the maximum gestational age for abortion from 20 to 24 weeks for certain categories of women, and the second time in 2022 to expand abortion rights to single women and “married women” who “may also form part of the survivors of sexual assault or rape”.

Moreover, India passed the Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques Act in 1994 to prevent the misuse of modern fetal sex screening techniques. This law was further amended in 2004 into the Pre-Conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (Regulation and Prevention of Misuse) (PCPNDT) Act to deter and punish prenatal sex screening and sex selective abortion. Ramya argues that the dual phenomena of female infanticide and and sex determination leading to female infanticide override any meaningful conversation, during elections and outside it, around access to safe abortions in an expansive way, especially for rural populations.

As we have reported (here, here, and here), access to reproductive services and abortion rights are still a challenge. People, especially single women, trying to access contraceptives have to experience moral policing and humiliation, while abortions are still expensive, compromise people’s privacy, and leave much to the discretion of private practitioners.

Also, unlike the US, the government-funded National Health Mission and subsequent maternal and infant programmes – such as financial incentives for institutional deliveries or prenatal diagnostic techniques – have helped women access reproductive health services, Ramya says.

But early legal and policy reform catered to family values and not individual concerns, as we said earlier, stressing only on married women as “vessels of reproduction”. Concerns of single women and gender-diverse persons were ignored.

Population Control Fears

If the US took a step backward with the legal reversal, India’s abortion regime is pro-women because it continues to make reproductive choices affordable and promotes safe motherhood, wrote the then Union Minister for Women and Child Development Smriti Irani.

But scholars like Gauri Pillai have argued that India’s legal reforms were concerned less with bodily autonomy and choice and instead “motivated by fears about population growth in India”. India launched the National Family Planning Programme as early as 1952, and population control soon became a point of political contention.

Sanjay Gandhi used his family planning drive to build charismatic leadership credentials, says historian Ramachandra Guha in India After Gandhi (2008). “Here was a Herculean project, the solving of which, everyone acknowledged, was vital if the nation hoped to survive, let alone prosper,” he writes. This focus allowed measures like forcible sterilisation during the 1975 Emergency, which violated international standards on reproductive autonomy.

Family planning is an easier vehicle to push, says Ramya, one without the ‘trappings’ from a feminist perspective. State-led population control measures become more digestible if packaged as efforts to ensure access to state resources and economic growth.

During the 1977 elections, the Janata Party that unseated Congress from its 30-year rule reminded people of the excesses, the state-sponsored population control in which 6.2 million Indian men were sterilised in just a year, which was “15 times the number of people sterilised by the Nazis”, according to science journalist Mara Hvistendahl. It also evoked popular anger against Indira Gandhi.

There have been reports of forced sterilisation among women and men for many years now but they do not become an election debate such as unemployment or inflation, says Ramya. In November 2014, 14 women died in Chhattisgarh due to botched sterilisation operations; the Supreme Court banned mass sterilisation camps in 2016 and called for the central government to shut down all such camps in three years. The ruling BJP has remained silent.

Forced sterilisation programmes disproportionately target women and men from resource-strained, rural communities, mostly from marginalised castes and Indigenous communities with poor access to contraception. There are instances where women and girls’ with disabilities were coerced into operations under the pretext of menstrual hygiene management.

“The larger Malthusian agenda of population control has also allowed populations to be treated as a testing ground for a lot of reproductive and contraceptive products that cause either temporary or permanent sterilisation,” she says, often in unsafe and unsanitary sterilisation camps.

Moreover, rising Islamophobia, more specifically propaganda about the community “overproducing”, has been used in election campaigns. This links in public imagination the ties between reproductive health and population control.

Low Representation Of Vulnerable Groups

In the Emergency era of forced sterilisations, officials were offered incentives to maximise the number of procedures conducted, including money, food, cars and so on, and they then set up a ‘quota system’ that health workers had to meet. “This disproportionately impacts women from caste-oppressed and socio-economically marginalised groups” who have higher unmet family planning needs and lack control over their reproductive health care, says Ramya.

The women most impacted by this coercion are also the least represented in political spaces of decision making at the lowest levels. Community health workers like ASHAs and ANMs play crucial roles in connecting these women with health services, implementing family planning policies and incentivising modern contraceptive methods. But they complain of the regressive mindset that disempowers women – despite their years of experience, most men still do not feel comfortable talking to them about contraception.

ASHAs’ experiences and gender-specific knowledge are rarely considered while crafting election campaigns, and their voices are largely excluded from policy discussions, says Sonal.

‘Ladies Ka Issue’

It is also difficult for sexual and reproductive rights issues to enter the election discourse in any meaningful way because government schemes on these under India’s federal structure are region-specific and often inconsistent, say experts. For instance, Rajasthan and West Bengal’s programmes to delay early child marriage or deter teen pregnancy were meant to address their high rates of child marriage and infant and maternal mortality.

Moreover, planks like infrastructure, jobs, or food security resonate more with both politicians and voters, because they hold visible outcomes, and appeal to male voters. Sexual and reproductive issues are dismissed as “private” or “ladies log ka issue (women’s issue)” despite their profound public health and economic implications, says Sonal.

Research shows that political conversation is confined to women’s reproductive health markers like nutrition or anemia levels with little reference to the problems of forced sterilisation and women-focused family planning.

If election manifestoes frame these issues as people’s ‘rights’, they would have to see women as people and accept their rights to bodily autonomy, sexuality, and reproductive autonomy as a human right, argues Ramya. But these issues are electorally invisibilised because of a “tremendous resistance to disrupt and critique central hegemonies like caste system and patriarchal practices”.

Some change, fragmented thought is now visible. This year, issues like female foeticide and sexual violence were clubbed under a ‘women’s manifesto’ released by a Catholic group. And health organisations like the Indian Medical Association as part of a ‘health manifesto’ outlined challenges to accessing sexual and reproductive health services for gender-diverse people. But unlike employment or the climate crisis, sexual and reproductive health is still not acknowledged as an unequivocal right, both by the elected and the electorate.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.