Caring and Fierce, Jailed Adivasi Activist Suneeta Pottam Fights Injustice Everyday In Bastar

She is an Adivasi leader, an activist, a farmer, a migrant labourer and an eager student. But the only descriptor the police have for her is ‘Maoist’

- Shreya Raman, Bhumika Saraswati

Suneeta Pottam was all of 23 when she, along with others, led a massive Adivasi protest of over 10,000 people in Silger, Chhattisgarh, against the illegal security camps in Bastar villages. During the stir that began on May 12, 2021, the protesters were fired at and lathicharged, killing four and injuring more than 50.

The Silger agitation lasted over a year, but a month after it began, the leaders of the protest decided to scale down their campaign as the farming season was approaching and COVID-19 was spreading. Men and women began packing up their belongings and getting into tractors to go home. It was getting dark with the chance of a downpour when the leaders of the protest were told that a few activists in Raipur were meeting the state’s Chief Minister and the Governor and that there could be a possibility for them to meet the officials too.

While the other leaders rushed to find safe passage, Suneeta would not budge from the protest site. “We were getting impatient and telling her to rush,” recalled Shreya Khemani, friend and a member of People’s Union For Civil Liberties (PUCL).

But Suneeta was busy moving from one tractor to another, ensuring that the protestors would have a comfortable journey home and that they had enough food, raincoats and petrol. The young activist’s fight against injustice has an everyday quality to it, said Shreya. “She doesn’t take the stage easily but all the care-work in a movement, all the running around that strengthens a movement, she did,” she said.

For almost a decade now, Suneeta has been fighting for the rights of the Adivasi people of Bastar and her campaign has helped uncover stories of extrajudicial killings and sexual violence by security forces. She co-founded the Moolvasi Bachao Manch, a forum for the rights of Bastar’s indigenous people. For this, she has received multiple threats, including death threats from security forces.

Today, at age 26, this slight, sprightly and spirited young activist sits in a women’s prison cell in Jagdalpur central jail, charged with murder, attempt to murder, loot, provocative speeches and causing damage to government property. She was arrested early June in a manner that raised questions about human rights and violation of laws.

Today marks one month of her incarceration. Suneeta is feisty but her friends and other activists tell us that more than anything else she is driven by her love for her community, her village and home, her large family and her zest for life. Her schooling was disrupted at age 9 by violence, and her one big ambition now is to complete her education.

Human rights lawyer and co-founder of the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group, Shalini Gera, was among those who visited Suneeta in prison. In a statement released after the visit she said: “In the hour she spent with us today, Suneeta went through the entire gamut of emotions. She bawled and howled, she was angry and upset. But she also collected herself, and enquired after everyone. And she was positively joyous at getting some achaar and even giggled shyly as she requested us to get her some bindis.”

Putting Suneeta in jail, Gera said, is like “locking up sunlight and putting a lid on fresh air”.

The Maoist insurgency, rooted in resistance to state and corporate efforts to divert forest land for industrial development, intensified post 1990s when the government started granting mining leases to private and multinational corporations. There have been allegations of human rights abuses, extrajudicial killings and violence against women in campaigns meant to quell the insurgency.

Since the BJP government came into power in late 2023, there has been a rampant increase in the number of encounters and security camps: the police claim that 139 Maoists have been killed in 2024 alone, highest since the state was formed in 2000. But not all of them are Maoists and include innocent villagers, Behanbox had reported.

‘We Will Never Yield Our Land’

When we met Suneeta in Bastar in April this year in the course of our election reporting, she said she was scared because she had received several threats to her life. “If they [police] catch me, they might kill me.” Less than two months later, police personnel in plain clothes barged into her rented home in Raipur, dragged her out and arrested her.

That was our second meeting with Suneeta. In October 2023, we first met her at Ambedkar Bhawan in Delhi where we spoke with her for an hour. All her comments in the article here come from these two meetings.

Suneeta’s arrest is the latest in a spate of repressive moves against the Adivasi communities of Chhattisgarh’s Bastar region. In one of the most militarised zones in the country, the indigenous Adivasi people have been the biggest casualties in the decades-long conflict between Maoists and the security forces.

Suneeta has played a significant role in lending mature leadership to the youth and women-led Adivasi movement, demanding state accountability and an end to all forms of violence.

“We will give our lives but not our lands,” Suneeta had declared, when we met her for the first time in Delhi.

Around 8:30 am on June 3, Suneeta had just finished her bath when the doorbell to her rented house in Raipur, that she shared with two other activists, rang. At the door she saw two men and a woman who claimed that they were relatives of her neighbours who shared a door with the flat.

The three barged in and tried to grab her. Screaming, she ran into her flatmates’ room. The “relatives” were in fact DSP Garima Dadar and other police personnel from Bijapur. They locked up one flatmate in her room and dragged Suneeta out and then latched the main door.

“She was held by her hair and dragged by male police personnel, slapped by a woman police officer, not shown any arrest warrant, not informed about the grounds for her arrest, nor given any time to communicate with her lawyer,” said the latest statement by the All-India Feminist Alliance that we received over email. The alliance is part of the National Alliance of People’s Movements, an umbrella body of civil society organisations and movements against discrimination of any kind.

One of the activist leader’s flatmates called Shreya who reached there in half an hour but by then Suneeta had been put into a vehicle. “I demanded to see a warrant and DSP Dadar flashed a document on her phone. I asked for a print out and one of the male personnel went and got a print out but they barely let me see it,” she recalled.

When Shreya asked more questions, the police threatened to arrest her as well. “It was laughable. I told them to arrest me. I said they have to do this properly and have to show me the warrant and let me meet Suneeta.”

The police personnel agreed and brought the vehicle around and rolled down the window. Suneeta was flanked by two women constables. “When I put my hand in, they rolled up the window over my hand and started speeding away. That’s when I noticed there was no number plate on the car,” Shreya recalled.

Interrupted Childhood

The reason Suneeta was in Raipur when she was arrested, over 180 km from her home in Bijapur district’s Korcholi village, was because she was in the midst of her class 10 studies.

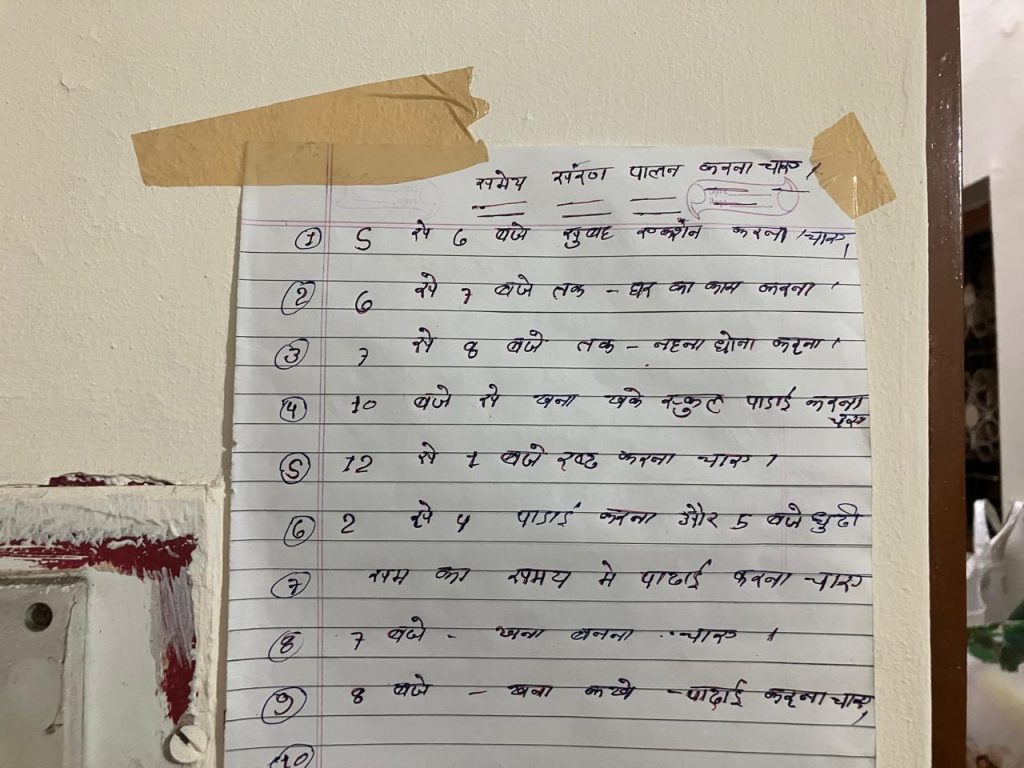

There is a handwritten timetable stuck on a wall in her room. An ideal day for Suneeta began at 5 am and after she finished her chores she would start studying at 10 am. Noon to 1 pm is reserved for rest and then again she resumes her studies, pausing only to make dinner at 7pm. Post-dinner again is study time.

“How she studied, oh my god. We would tell her to stop and take breaks but she just wouldn’t listen,” said Shreya. Suneeta had taught herself Hindi and was trying to learn English. “Once she called me at 10:30 at night to ask what upabhokta (consumers) meant. She was reading about consumer law.”

When she had come to Raipur, Shreya was still figuring out the books to give to Suneeta. “We gave her copies of this newsletter that our students of class 5 had written. She sat down and copied every article in her notebook and called me to ask the meanings of every word that she did not understand,” said Shreya, adding that Suneeta was keen that all young people in Bastar be educated. “She always regretted that she couldn’t study.”

The last time Suneeta went to school was when she was 9 years old and studying in class 4. The government-supported militia Salwa Judum, set up in 2005, took over her school and turned it into a camp. These teams conducted violent raids in villages in the region until the Supreme Court deemed them unconstitutional in 2011.

Suneeta’s village Korcholi is a testament to the resilience of the Adivasi community. It is a quiet village, like many others in the Bastar region, despite the brutality it has witnessed, the stories of its people, especially women, have often been lost in the din of violence and repression.

The first time Suneeta was questioned by a policeman she was just 10 years old and had gone to a market with her elder sister, journalist Niha Masih wrote in 2018.

The next year, Suneeta’s village bore the brunt of the Salwa Judum’s wrath – homes were reduced to ashes, and the air was thick with the cries of the beaten and bereaved Adivasi population.

“I still remember how we lived during Salwa Judum, our situation was very bad,” Suneeta said, her voice steady yet heavy with the weight of the past. “We used to live in the forest and try to survive by eating onions. Our parents fed us whatever was available to keep us alive.”

Their home was burnt down thrice, the activist recalled. “Our clothes were burnt and we had absolutely nothing left to wear.” These stories were echoed across homes.

Had To Speak Up

It was Suneeta’s fury against injustice and impunity that made her an activist at age 17.

In 2015, when a fact-finding team from the Women Against Sexual Violence and State Repression (WSS), a non-funded grassroots efforts reached Suneeta’s village in Korcholi, they uncovered stories of brutal atrocities on Adivasi people by the security forces.

“I remember the young girl in a skirt and top reiterating again and again in broken Hindi that what was happening was wrong,” said Shreya, who was part of the WSS fact-finding team. “That was the first time I met Suneeta.”

According to Suneeta, in one of the security operations in her village, a woman had been raped and an innocent villager had been killed. “I decided I have to speak up because if I don’t, nothing will change. You have seen how people in my village can only speak in Gondi. I knew little Hindi so I had to speak up,” she told us.

Next year, she and her neighbour Munni Pottam, with support from Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group, filed a plea before the Bilaspur High Court against the extrajudicial killings. This case was later transferred to the Supreme Court and tagged with another case, popularly known as Salwa Judum case and is still pending.

Suneeta was also one of the villagers who spoke against the sexual assault and harassment of over 40 women and the gangrape of at least two in 2015. “The police had denied these allegations and tried to throw it aside as Maoist propaganda,” said senior independent journalist Malini Subramaniam, who has been consistently reporting from Bastar since 2015. These allegations were later found to be true by an independent NHRC enquiry that led to the order of compensating the women survivors, she added.

Her knowledge of Hindi also makes Suneeta an important link to get news of violence from Bastar to activists and journalists. She has accompanied human rights activist and lawyer Bela Bhatia on several fact-finding missions near Korcholi. Bela Bhatia said Suneeta is rooted in her region, refuses to give in to pressure and is relentlessly persevering.

Suneeta was one of the key figures from amongst the nine young Adivasis who negotiated with MLAs to push an enquiry into killings by police firing in Silger in May 2021. That year, she also co-founded the Moolvasi Bachao Manch along with Raghu Midiyami, Gajendra Mandavi and other young people from Bastar. The forum was formed specifically after the Silger firing to highlight the issues of moolvasi (indigenous) people, said Vinesh Podiyam, secretary of the Manch.

Poet and novelist Meena Kandasamy who was struck by Suneeta’s resilience when she met her during the Silger protests said: “She was one of the victims of Salwa Judum, having seen her own house burned down and having to hide in the forest. She was trying to prevent the repetition of what had happened to her.”

‘Who Will Tend To My Farm?’

In 2016, Suneeta started receiving threats from the police when she and Munni approached the High Court, and has filed at least five complaints with the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), district authorities and the court, fearing for her safety.

Two years later, Suneeta wrote to the collector saying a few police personnel threatened to kill her if she did not stop speaking up for the villagers.

Recently, on February 9, she had gone to Bijapur to visit her friends who had been hospitalised, when two police personnel accosted her and told her to accompany them because a senior police personnel wanted to speak to her and get her signature. “When I refused, they grabbed both my hands and snatched away my phone. At 2 pm, in the middle of a busy road, how can these two male personnel grab a woman like this?” she said.

A local journalist, who happened to be nearby, intervened and insisted that the personnel give it in writing that they are detaining Suneeta. Soon, two more people joined to help Suneeta, forcing the policemen to retreat.

“After that, for a month, I stayed away,” said Suneeta. “But soon, I started longing for my village. I had sown tomato plants in our farm and I was worried – who would water and take care of them? It was also time to start collecting mahua and chironji fruits. So, I decided to go back home.”

But before Suneeta could reach her village, the police had already arrived in search of her. “I was in another village and on my way when villagers called me and told me that police had camped there for two days waiting for me. I went only after they left because I was scared that if they caught me in the village, they would kill me and call it an encounter or rape me. Living in my village has become a big problem,” she said.

All of Suneeta’s four sisters are married and since the death of one of her two brothers, much of the responsibility to financially support her family has shifted on her, said Malini, who has known Suneeta since 2018.

Solidarity On A Telangana Chilli Farm

To earn for her family, Suneeta, like others in the region would often go to work at the chilli farms of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana during harvest season as a farm labourer. To delve into her life beyond activism and to understand the work of Bastar Adivasis during chilli harvesting, Malini followed Suneeta to a village close to Cherla in Telangana’s Bhadradri Kothagudem district in May 2022.

“On the banks of river Godavari, thousands of temporary huts made of bamboo and plastic and cloth sheets were constructed to enable their stay in that heat for a month and above,” said Malini, who also recalled aspects of Suneeta’s life beyond activism: the gruelling days of plucking chillies from 9am to 5pm that began with a quick early meal of rice and dal and ended with cooking, early dinner and a group dance to shed the exhaustion and monotony of the day. As the day ended, there was camaraderie over music and humour despite the hardship.

One evening when Suneeta was chatting with her friends two women approached her, said Malini. As the women narrated their travails, a pall of gloom settled over the group. One woman’s husband and another’s brother were picked up by Bastar police when they had gone to a nearby market to buy groceries. The women had travelled back to Bijapur to look for them but the police had denied taking them.

“They were appealing to Suneeta to help them find as they feared they might be killed as Naxals,” said Malini via email. “With a deep sigh Suneeta got up to call local journalists in Bijapur to find if they had any information of the arrests of two men. To many in her village and in nearby villages, Suneeta Pottam was the ‘go-to’ person with their troubles, especially with the police.”

When asked if she is scared of the threats, Suneeta told us: “Why should I be scared? I need to be scared only if I do something wrong. My fight for our rights is based on the rights given to us by the Constitution.”

Following Constitutional Path, But Branded ‘Maoists’

For Suneeta, the story of Bastar and its people were inseparable from her own. When asked to talk about herself, her first thoughts were about Bastar. “They are making camps every two kilometres inside our villages. They are building big roads for the mining companies’ convenience. The police authorities are abusing, assaulting, and raping women inside the forests. Why are the people who are responsible not being punished?” she asked in frustration. “Even after us going to jail, why are there no reports?”

When Meena Kandaswamy met Suneeta, she saw a courageous and articulate leader. “She found ways to do mass mobilisation that I found incredibly powerful,” said Meena adding how most Silger protesters were young people who had witnessed the ongoing conflict while growing up. “They are trying to criminalise them while they’re young, trying to make sure they spend their best years in prison,” she said.

The police called Suneeta a “key operative of the Maoists’ urban network and frontal organisation” and said that there are 12 pending warrants against her for offences related to murder, attempt to murder, loot, provocative speeches and causing damage to government property.

“They can arrest me only if they brand me as a Naxal,” Suneeta told Behanbox in April. “Because there is no other way they can arrest me. We have no association with Naxals, we are Adivasis who are trying to survive by working on our farms and doing labour. We are fighting for our ‘Jal, Jungle, Zameen (water, forests and land)’ and for our rights that are given to us by the Constitution.”

Malini pointed out the irony in a young activist treading the constitutional path to justice being arrested on charges of being a Maoist. She is not the first to face this. Activist Soni Sori was arrested in 2011 and was accused of sedition, only to be acquitted of all charges a decade later.

On April 2, 2024, police personnel raided senior Adivasi leader Surju Tekam’s house and arrested him after charging him under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) for being a “Maoist sympathiser”. His family members allege that literature associated with the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist) (CPI(M)) and weapons were planted in his residence by security forces.

Gajendra Mandavi, who co-founded Moolvasi Bachao Manch with Suneeta and Raghu Midiyami, has also been in jail since May 2023. In March 2021, when activist Hidme Markam was arrested, the then Superintendent of Police Abhishek Pallav said that cases against her were “foolproof” and that he will get promoted to the post of IG (Inspector General) before she even gets released. But within two years, Hidme was acquitted in four of the five cases and was released on bail in the fifth. But just last month, a police personnel threatened her, she said, saying: “You have not amended your ways despite going to jail. Should we put you back or do you want to die?”

Call For Suneeta’s Release

Hidme also visited Suneeta in jail on June 6, along with her family members, other activists and lawyers. “She started crying a lot after she saw her mother,” said Hidme. “We tried to pacify her and told her that one day she will be out. But she continued crying. She was worried about who would take her mother to the hospital to treat her wounded leg.”

The All India Feminist Alliance called Suneeta’s arrest a part of the larger phenomenon of criminalising grassroots organising, political dissent and civil liberties. “In a state where the denial of constitutional protections is the norm, both her marginalised socio-economic status as a young adivasi woman and her uncompromising activism are seen as an affront to the powers that be,” the statement said. Meena too has demanded that she be released and cases against her be withdrawn immediately.

Mary Lawlor, a United Nations Rapporteur on Human Rights Defender, posted on X calling for Suneeta’s release and said that her arrest was seemingly a result of her peaceful advocacy for the protection of Adivasi rights and against systemic violations.

“She was already telling me about how she was trying to be silenced, which is when I realised how precious her voice was,” said Meena.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.