Why Surveillance Measures Will Not Ensure Women’s Safety

The numbers do not tell the complete story of violence against women and this means that the measures based on existing evidence are inadequate too

I conducted a rapid survey in March 2024 to understand how safe women feel about loitering about in New Delhi. Only six of 101 women classified the capital city as safe.

“[Delhi] is safe for women who are watchful and consistently careful,” said one woman. Others said that time, place, and context matters in how safe the city is. The onus, it was clear, was on women themselves to ensure that they remained safe by not letting down their guard or being at a wrong place, wrong time. They did not bank on the government to ensure a safe environment for all genders.

What does women’s safety look like in India today and how does the government measure it? In this article, I argue that India needs to reimagine the social interpretation of women’s safety because existing crime statistics are unreliable. I also discuss why public initiatives need to break away from surveillance-based measures which place the burden of proof of redressal on the survivors of violence.

Under-reporting of Violence, Low Redressal

Crimes against women increased by 4% between 2021-22 and 2022-23. In 2021-22, it increased by 15% from the previous year. Uttar Pradesh reported the most (15%) crimes against women in 2022-23.

What do these numbers suggest? One, that more women are able to access institutions of justice, such as the police, and report crimes. And second, that women might be increasingly vulnerable to violence and discrimination in India. The reality of women’s safety in India is, however, more complicated than this.

Data on crime against women is released annually by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). But it confronts a statistical complexity: only crimes that draw the highest penalty are reported. For instance, ‘murder with rape’ is only reported as ‘murder’ as the latter attracts the maximum penalty. This is done to prevent double counting of offences which dilutes the overlapping incidence of violence. For instance, physical violence may exist with emotional violence but the IPC does not recognise such incidence and sees crimes in isolation.

Another dataset capturing violence against women is the National Family Health Survey (NFHS). The NFHS, however, only reports instances of spousal or domestic violence. Over 32% of women experienced spousal physical, sexual, or emotional violence in 2019-21. Under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) provision of ‘cruelty by husbands or relatives’, 31.4% of such instances were reported in 2022-23, constituting the majority cases of crime against women. While NFHS is more nuanced in its reporting of spousal violence (for instance, it also measures the intergenerational effect of violence), the NCRB considers a range of IPCs which include violence in domestic and public spaces (acid attack, kidnapping, etc.).

Devoid of any other sources to measure violence against women in India, my colleagues and I conducted an analysis for estimating how many women may be experiencing violence assuming under-reporting in NCRB’s data. We also sought to understand how under-reporting translated into accessing benefits under the government’s One Stop Centre scheme for survivors of violence. It is funded through the Ministry of Women and Child Development’s (MWCD) largest fund for safety measures, the Nirbhaya Fund. One Stop Centres were established in 2017 as one-stop redressal sites for women to file an FIR, seek medical and legal help, and access short-term stay facilities.

The findings were revealing: assuming a minimum (30% women in bottom wealth quintile) and maximum (90% women in bottom three wealth quintile) under-reporting in crime against women, more than 1 lakh and 63 lakh survivors, respectively, would not have been able to access the scheme’s benefits in 2021-22.

Under-reporting of crime against women further under-estimates needs for women’s safety measures. The NFHS reported that only 6% and 3% women, respectively, sought help from the police or social service organisation (61% women seek help from their own family). One primary reason for this is that these institutions push for reconciliation with perpetrators for keeping crime numbers low. BehenBox also reported that justice for Dalit survivors is further compromised because of the caste dynamics involved.

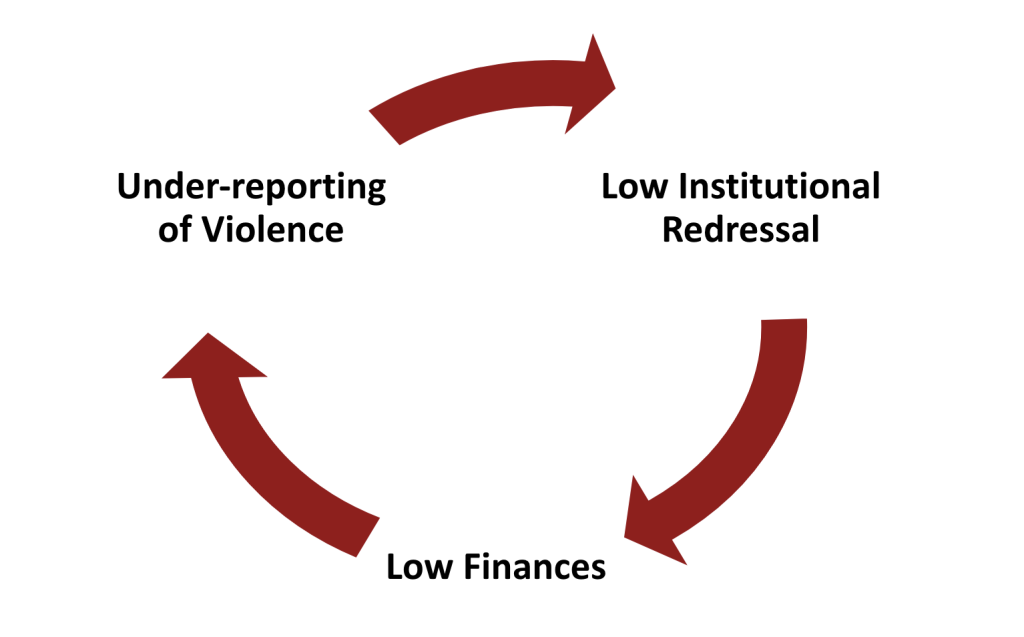

But, spending under the One Stop Centre scheme has been decreasing since 2018-19. And, with the barriers to institutional redressal, we now find a vicious cycle of under-reporting and low financial prioritisation for women’s safety measures in India (Figure 1). This means that if violence is under-reported, the government will incorrectly assess needs and finances for its safety measures.

So, how can the government improve access to justice for survivors of violence? Investing in sensitising the police force, promoting awareness among women about the existence of redressal sites such as One Stop Centres are some ways. But, in reality, how is women’s safety in India being prioritised? We find that the government’s interpretation of women’s safety comes at the cost of their ability to (re)claim spaces.

Focus on Surveillance-based Measures

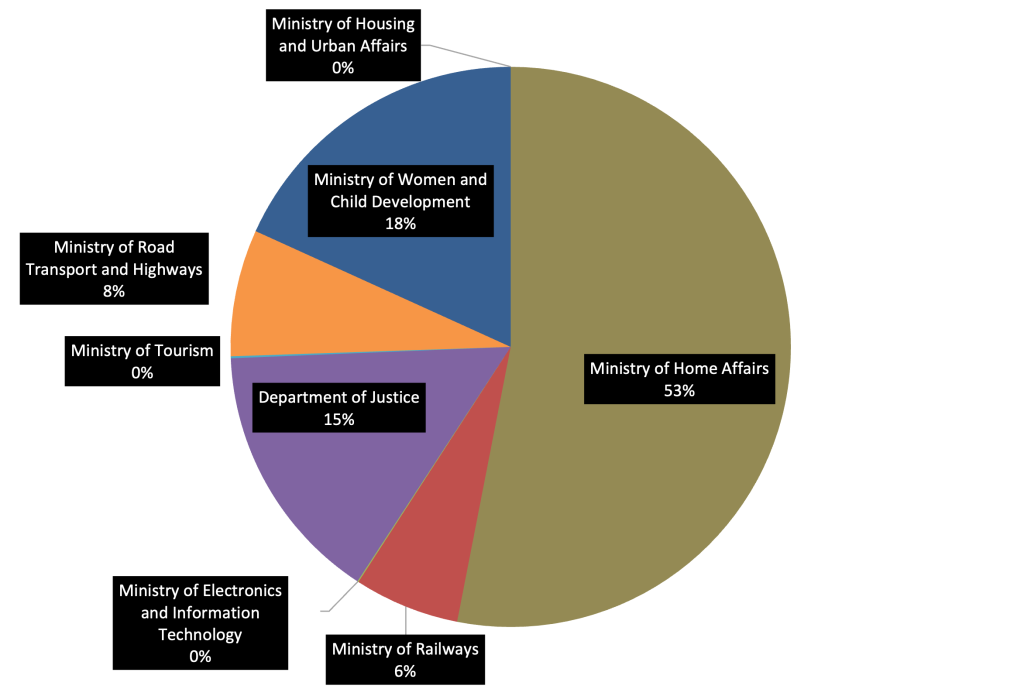

The Nirbhaya Fund was launched after Jyoti Singh’s rape and murder in 2012 with the vision to prevent violence against women in public and private spaces. Under the Fund, the MWCD has 14 projects and the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has 12. But, of the Rs 5448 crore released between 2015-16 and 2023-24, MHA’s projects received the most (53%). This seems counterintuitive, considering that the MWCD is not only the nodal ministry of the Nirbhaya Fund but also has the mandate for “[women’s] development in an environment free from violence and discrimination”.

Across projects under the Fund, surveillance-based interventions for women’s safety are prioritised. For instance, the MHA received Rs 1,577 crore for the Safe City Mission under which “smart surveillance” is one of the components. At the same time, the Ministry of Railways and Ministry of Road Transport and Highways have, respectively, come up with proposals under the fund for “AI-based facial recognition system integrated with video surveillance” and “state-wise vehicle tracking platform”.

Using the Fund, the MHA also aims to “set-up women-help desks in police stations” (Rs 158 crore), train “investigation and prosecution officers” (Rs 41 crore), and so on. But, compared to surveillance-based measures, these do not seem to be prioritised. One Stop Centres have received Rs 854 crores since 2015-16 but, as previously mentioned, the spending has been consistently low (Rs 385 crore was allocated in 2020-21 but only Rs 160 crore were spent). Rajya Sabha’s Action Taken Report on Women’s Safety in 2022 had also reflected the under-utilisation of projects under the Nirbhaya Fund by the MWCD, I had analysed before.

Moreover, the evidence on women-help desks is mixed. An experiment in Madhya Pradesh found police stations with women-help desks were indeed reporting more crime against women compared to those without them, while another study in Haryana found that all-women stations reduced female officers’ overall caseloads and also pushed survivors towards reconciliation.

MWCD’s new proposals also include installing CCTV cameras in public spaces. Instead, it should focus on projects that comprehensively improve access to public spaces. The One Stop Centre is one such project that helps build “gender transformative” public spaces. Surveillance-based measures tend to limit women’s access to and reclamation of these spaces. As this incident on Delhi’s Metro line showed, the push for surveillance-based measures is not helping women access the city any better in the face of institutional indifference. These measures instead suggest that CCTVs will capture crimes because spaces are unsafe for women.

BehanBox’s Feminist Election Newsroom has created accessible video voting guides to equip our audience to become an informed voter. We have explainers on “How To Register Your Vote As a First Time Voter” – English, “अपना वोट रजिस्टर कैसे करे? – Hindi”

“How To Shift Your Vote If You Have Migrated”, “How To Update Your Gender and Name On Your Voter ID”, and “How To Mark Yourself As A PwD Voter”.

We have more resources coming up. Keep watching this space for more. To sign up for BehanBox’s Feminist Election Newsroom, click here.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.