[Readmelater]

Why A Dalit Woman Is Demanding A Cremation Ground For Dalits In Her Village

In rural Maharashtra, landless Dalit families often struggle to find space to cremate their dead. Pramila Zombade wants that to change

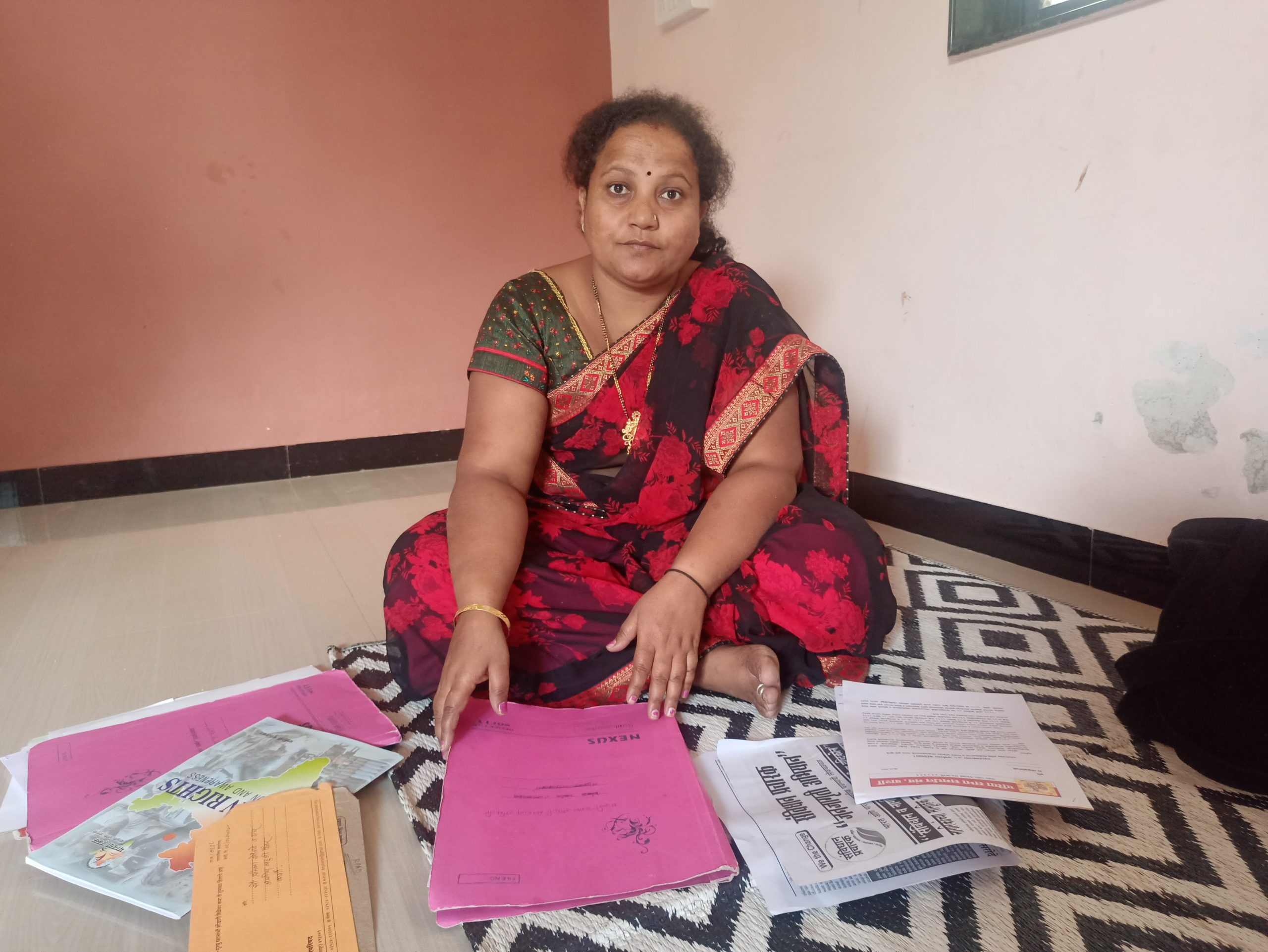

Pramila Zombade a social worker based in Barshi, Solapur has been relentlessly fighting for the rights of Dalits under Panther Lahuji Salave Sanghatana, that advocates for non discriminatory, constructed crematorium in her village/Priyanka Tupe

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.