“50, Fat and Frumpy: Our bodies deserve respect”

In conversation with playwright Jyoti Dogra, whose new play Maas discusses patriarchy, capitalism and our bodies

Jyoti Dogra’s plays never let you sink into your seat. They take you to the edge, and you are laughing, crying, cringing and sometimes doing all at the same time. Her breakthrough work, Notes on Chai, was a collage of everyday urban conversations marked by humour and pathos but also framed by unusual physical and vocal experiments. The next, Black Hole, delved into a dying woman’s preoccupation with astrophysics.

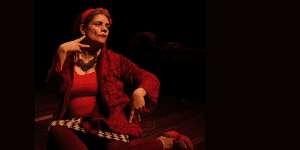

Maas, her latest work, premiered in May this year. As the stunning play opens, a woman with a body that has clearly aged, moves in a slow-motion pantomime of ramp walk. Over the next 100 minutes, Dogra becomes a dozen women struggling with the shame of owning a less-than ideal body – overweight, menopaused, pimpled, chin hair-ed, paunchy. She clutches the roundel of fat around her belly and screams in despair, fights the urge to have that next chip, and drowns in endless blather about beauty hacks – dermabrasion, surgery, botox and how to dress to look slim.

It is an acutely and often uncomfortably personal work mostly because we all see ourselves in it. In an interview with Behanbox, Jyoti Dogra talks about the ideas of body and shame, how the beauty industry has taught us to separate ourselves from our bodies, leaving us in a state of eternal dissatisfaction with ourselves. Excerpts from the interview:

What sparked the idea for Maas?

There was a gap of around five years between my play Notes on Chai and the next, Black Hole. And many of my community of regular viewers and friends, who were seeing me after a long interval, reacted with a: “You’ve put on weight.” This really intrigued me. It is not like I did not know that I had put on weight. It is not that they were being bitchy, they were well-meaning people who love my work. But there seemed to be a pressing need for everyone to comment on my weight. Then I thought this would make for a great play after something intense like Black Hole – about me getting fat and old.

Fat people trying to lose weight – that is always supposed to be funny. We draw a direct connection between fat and shame.

Everything around me was screaming, ‘not young, not pretty, shame’. The social media, the banners, the clothes industry. And they didn’t need to because I am telling myself I am fat. I am policing myself and failing. The beauty industry sets us up to police ourselves and fail. In all this we forget that this body is ours, it is the very first relationship we have in the world. But we have begun to separate ourselves from the body. The hunger is separate from us, the sugar craving is separate. It is us vs our bodies.

I put on 8kg of weight for the play between November last year and this May. I didn’t feel particularly fat, I realised, because I have always felt fat. No matter what my weight, even when I was 17 kg lighter I felt fat.

You talk of being ‘50, fat, frumpy’ and invisible when you enter a public space now. Wasn’t this always the case?

There has always been this thing called beauty privilege, the advantage you have as a beautiful person where everyone wants to associate with you. ‘Have you seen X? She is so beautiful.’ But earlier it was seen as a gift from the gods, a rare thing. Today if you are not beautiful there has to be something wrong with you because beauty can be bought and sold and there are entire industries riding on it that don’t let you forget that. Beauty is now a currency, a commodity.

This means that you are failing everyone around you if you are 50, fat and frumpy. A lot of people tell me that I am ‘brave’ to appear on stage without hiding all that is ‘wrong’ with my body. Because you are supposed to hide these flaws, with clothes and make up, as a sort of apology to the world. It is like we have to say: I am sorry for this version of myself.

Everyone has to look prepubescent. Even after two children. Look at our clothing sizes. We are going from Small to XS to XXS.

So, in a sense, things were better earlier because there wasn’t this intense pressure to look flawless? Post-birth for instance your body could change and you did not have to look thinner than you did before within weeks.

I think women had a lot more agency with their bodies earlier though they didn’t have financial agency. Now we are urban, educated, independent but we are insecure about our bodies. This is how the patriarchal system and capitalism ensure control over women. You may be a CEO of the company but you are failing the world by not looking good enough. It is never enough, young enough, fit enough, pretty enough.

My dilemma was who would I cast if I wanted different bodies in stage as a way to show different types of flawed bodies. Dark, fat, old…an ensemble of less than perfect bodies. But I decided I would only cast myself and I would work with my body and all that goes with it. It is more personal that way. I can talk about age, menopause, chin hair, paunch, shame. There was no generic discourse here, it was a very personal stance. It was all so internalised, my view of my body. But it would draw others in starting from there.

Every word used to describe a less than perfect body is derogatory and mostly used for women – turkey neck, bat wings, muffin top, love handle. Being fat now is connected with a weak character – [you must be] lazy, dumb, stupid. By not looking perfect we have not just failed ourselves but everyone around us. We are set up to fail; the younger and prettier you are the more guarded and troubled you are by the fear of not measuring up because beauty has become integral to your self-worth and you cannot lose it.

You have a parjaiji, the old-fashioned matron in your play, who refuses to accept that she is – ‘Main moti hoon hi nahin’ was her refrain. I found her admirable despite her obvious comic lines.

She always gets laughed at. But I always ask, why do we laugh at her? Why not be inspired? Our view is that she cannot look like this, in her old-fashioned way, comfortable with her imperfect body, and be confident. How can she talk about her sex life? Our shame is judging her.

Today, the tyranny of the body is far more stringent even if other patriarchal tyrannies have eased. Beauty is the privilege of the rich – trainer, gym, protein shake, juice, quinoa, salad. In our lives, between work and care, when do you go to the market, buy fruits, squeeze? Where is the labour that will do this for us?

There is a massive industry that will collapse if it allows you to believe that you are beautiful. All this talk of the body being a temple only applies to a limited set of people. Even in ads featuring these so-called real bodies, there is nothing real about them, there is always symmetry.

The audience response to your play has been very visceral and deeply personal. Did you anticipate this?

What has surprised me is that a lot of this comes from young people, both men and women in fact. ‘This happened to me.’ Or ‘I do this’. You would think the young are a lot happier with their bodies but in reality, they have to deal with shame much more. At 50, I have made myself a space in the world with this body I have but at 20, your body is always on trial and you are required to answer for it.

On social media now we have a lot of talk about lookism and ageism and slogans like ‘Be fit at 60’ and ‘Young at 70’. Earlier we left our bodies alone, it was a medium to live. They are now things to look at, be looked at, totally objectified. I don’t say we don’t pay attention to our bodies but step back and look at how much of this we are doing for ourselves, how much for others, how much to conform to the insidious messaging from the beauty industry.

Do you think we are not kind enough to each other?

No, not just that. When I was doing my research, I looked at the food, fashion, fitness, and the entire multimillion-dollar beauty industry that pressures us to look good at all times and ages and conditions.

Consider the celebrity bullshit, I find it cruel and immoral to not disclose the full picture. ‘Oh, I am a vegan/I am a hands-on mother, that is how I stay waif thin’. But you have entire teams of a dozen people costing thousands a day, dieticians, trainers, and, of course masseurs, to ensure that your exercised body is comforted. But what if you are commuting for hours, have a child to care for, a home to run and you are pitted against this, being told you are not building enough muscle? That you have to live this hard life and then come home and eat a salad before you go to bed while your body is screaming for a large plate of hot dal-chawal. The labour and emotional cost of looking slim and beautiful at all times is immense and it must be acknowledged to put forth a complete picture of what it entails to look fit and fashionable.

I am up on the stage and you see my body with all its flaws and you get it. This could be you. I have been taken aback by the number of me who have told me how they connect with the play, because men and women are both victims of patriarchy and its idea of beauty.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.