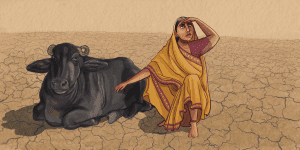

How Assam’s Human-Elephant Conflict Is Impacting Women’s Physical And Mental Health

When entire fields and homes are flattened by elephant movement, it is the women, as primary caregivers, who deal with acute anxiety and deprivation

- Aatreyee Dhar

For years, Archana Rai would wake at night in terror every time she heard a bamboo stalk snap or the bark of a banana tree being stripped. She would be gripped by the fear that elephants were rampaging through her family’s fields in Sagunbari 2, a village in the Udalguri district of Assam. She would wake her husband and together they would climb the stilt outside their home and keep watch over their paddy fields.

Rai’s fear was not unreasonable. She still remembers the night of November 2021 when she and her husband woke up at dawn to find that half the produce on their 3 bigha paddy farm had been wrecked by elephants. The family had to then buy rice for itself, an added burden on their sparse earnings. Rai’s husband, Hemanta, is a carpenter who earns around Rs 12,000 a month by working in neighbouring cities as a migrant worker. The rice they lost had been worth Rs 10,000 that month.

Rai’s village falls within the larger Chirang-Ripu elephant reserve which is dotted with agricultural settlements, tea estates and reserve forests. The area sees substantial elephant movement for six to seven months a year, and this happens through all the agricultural settlements and tea estates.

While there have been many studies on the human-animal conflict (here, here and here), there have been very few on its gendered impact. These impacts have gone uncompensated and unnoticed because they are psychological or social in nature – the hidden costs of the conflict.

As is the case with many families, Rai’s husband is often away on work when the elephant rampage occurs. “Invisible or indirect impacts are less visible, yet important impacts that go beyond the usual Human Elephant Coexistence (HEC) index – the number of deaths, injuries or damage to homes and crops caused by the conflict. Since [invisible impacts] are difficult to quantify, they tend to be neglected when we try to understand the impacts of, and adaptation, to HEC. Such effects include loss of sleep, deterioration of health including mental health and increase in workload, expenditure and so on,” said Sayan Banerjee, a prominent elephant researcher based in Assam, and a PhD scholar at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bengaluru.

These impacts are not felt on the day of damage but over a period of time, said Banerjee. This also means that they tend to be long-lasting, and since they are difficult to monitor, they do not get much space in conflict mitigation strategies and remain uncompensated and unacknowledged, he added.

The stretch of Assam straddling Bhutan in Udalguri district has been a hotspot for the human-elephant conflict ever since habitats started shrinking owing to mass-scale deforestation and illegal timber smuggling during the Bodo rebellion of the 1980s. As their habitats reduced, elephants carved out their migratory routes through sprawling tea estates and human habitats, stoking incidents of man-elephant conflicts in the state.

Solar Fencing And Its Impact

The elephant rampage stopped once the village was encircled with a solar-powered fence a year ago by Aaranyak, an NGO focused on conservation, in association with the forest department. The fencing included all of Sagunbari 1 and 2, barring the tea estates to allow elephant movement. At dusk, power is turned on in the fences and when the elephants come in contact with the wires, they get a mild shock.

But the solar fencing strategy may not remain effective for long. Elephants are now working around it – they either break the fence with their flanks that can withstand light shocks or attempt to cross during the day when the fences are not powered. “During monsoons, violent storms loosen the bamboo posts making it easier for elephants to push through into the fields. Also, when strong winds sweep leaves onto the fence, the flow of power is impacted,” said Rai. This happened in July this year, when an electricity breakdown did not allow the fence to be fully charged and elephants broke through the barrier and had to be chased away, she said.

Over 70 people and 80 pachyderms die every year on an average in the state, according to a 2023 statement by the state forest minister Chandra Mohan Patowary made in the Assam Legislative assembly. Between 2001 and 2022, 1330 elephants died in the state, with the highest number of deaths reported in 2013 when 107 pachyderms died, followed by 97 in 2016 and 92 in 2014. The minister did not reveal the number of human casualties. The Assam Forest Department estimates that 8333 houses with approximately 1400 hectares of cropland were damaged between 2007 and 2016.

However, an RTI response accessed by The Indian Express estimated that about 3938 human lives were lost to wild elephant attacks between 2014-2022. Assam was the second highest state to record most deaths on account of such attacks. There is no gender disaggregated data on this.

Women Starve To Feed Their Family

For Rai, crop-raids by elephants during the paddy farming season mean a steep drop in the household’s food supply. Such losses have deeper implications for women who are the primary caregivers for their families. In interviews, they told us that they would often starve to feed the rest of the family.

Two years ago, in September and October, when an elephant raid destroyed half the crops in her farm, Rai had to skip meals during the day. “When almost half of the paddy crops were destroyed, I ate once a day to ensure that my family ate three times a day. Then we began buying rice from the markets in neighbouring towns,” she said. In 2019, when tea garden worker Alisha Munda’s husband was killed during an elephant chase, she lived on salt and rice to make sure her three children ate well.

In her paper ‘Human-wildlife conflict and gender in protected area borderlands: A case study of costs, perceptions and vulnerabilities from Uttarakhand, India’, researcher Monica Ogra said that it is normal for women to make such adjustments because a broader set of Indian values encourage women to make individual and collective sacrifices for the well-being of the family.

“Yes, it happens often [although] in a place like Assam where food poverty is less severe than, say, in central India the effect might be less pronounced. Having bad nutritional health due to HEC affects women’s long-term health and the impact is slow, it is difficult to monitor. So conflict mitigation strategies can’t cater to this easily,” said elephant researcher Sayan Banerjee.

Working Twice As Hard

As we said earlier, when solar powered fences were constructed, the tea estates were excluded to allow elephants free movement. But this also means that tea garden workers, mostly women, have to live with elephants marking their presence when they are picking tea leaves.

Bijili Sahu, 45, is used to men guarding the gardens with tractors when elephants are around. But Sahu, who was abandoned by her husband 16 years ago, said this hampers the women’s work. “There are times when we have to stop our work till the elephant moves away on its own. We have to work twice as much during those days so that our weekly payment is not impacted,” she said. She has had to work hard till recently when her two sons started working.

Still, there are times when workers run into elephants who suddenly appear out of nowhere. On the last Saturday of April, when Sahu was returning home after standing for long hours in a queue to collect her weekly cash payment, she came across a male jumbo who stood in her path and refused to budge. Had her co-workers had not huddled around her and the men not burst firecrackers, she may not have survived the encounter, she said. “I am so used to the cries of elephants in tea gardens that I cannot sleep thinking one will knock me down someday,” she said.

Toll On Mental Health

The onus of chasing elephants away from farms and estates is entirely on the men. In one such incident, in 2019, when a male tusker had trampled through a rice farm, three men had chased it into a neighbouring tea garden late at night. One of the men, Anju Munda, was stamped to death by an elephant. His wife, Alisha, is a temporary tea garden worker, and she refuses to speak about the incident and its aftermath. Her friend and neighbour Aarti Bhengra had to recall Munda’s ordeal following her husband’s death. Munda had received a compensation of Rs 4 lakh from the forest department within a year of her husband’s death. The only property she owns is one-half of the betel farm and she lives in a kuchha (temporary mud) hut at the edge of the Orangajuli tea estate.

As we said earlier, Munda starved herself to feed her three children. She would, at times, rope her eldest daughter into household chores. There were days when her grief and anxiety about navigating her life alone would paralyse her.

“Her husband was a carpenter, earning Rs 300 daily. Both of them would share the family’s financial expenses. Now, she goes to the tea garden only twice in a week though her children insist that she continues to work for the family,” said Bengra, who is also related to Munda.

“My mother goes to work for a week and then she doesn’t for the next three weeks,” Munda’s daughter said.

The paper ‘En-gendering human wildlife interactions in northeast India: towards decolonising conservation’ by Sayan Banerjee and Shalini Sharma, associate professor at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IISER Pune, talks of this disruption in the lives of women in the region.

“Disruption of work at tea plantations due to the presence of elephants forces women labourers to work beyond working hours to maintain the same output desired by plantation managers. Several families in this landscape have become de-facto women-headed households due to the migration of men to urban centres. Without any choice of opting out, women have to continue using the elephant-dominated spaces to carry on domestic and productive work. The continued use of such spaces also takes a toll on their mental health with increased levels of fear and anxiety,” the scholars write.

In none of our interviews did the women blame the elephants for their condition. They seemed resigned to their fate, describing their tragedies as “God’s will”. At times, they blamed humans for destroying forests and forcing the pachyderms out of their habitats in search of food.

Men often use alcohol to cope with the suffering and resentment rising from the cost of the conflict. But the women have to simply deal with loss. “There is no ecosystem that facilitates the social catharsis of women for their loss, abandonment, grief, anguish or even rejection by the system that handles the mitigation of human-elephant conflict. Unfortunately, such issues might never gain the kind of political currency that could voice the mental health issues of women of the area,” scholar Shalini Sharma told Behanbox.

No Women’s Representative

Solar fencing has put a stop to elephant raids, said the villagers of Sagunbari 1 and Sagunbari 2. Ransai Basumatry is the head of the village committee that looks after the maintenance of the fence. All the members in the committee are male, he said, and one of them supervises the collection of funds from households to employ a guard to maintain the fence. Everyone contributes what they can, between Rs 50 and Rs 100. The guard walks the length of the fence to check for leaf piles on fences that could short-circuit the flow of power or to fix a post damaged by an elephant attempting to cross the barrier.

Basumatry and the other committee members we spoke to believe that dealing with the elephant issue is a man’s job. The women said they feel left out of mitigation efforts. They can, they pointed out, at least guard the fence, if not chase elephants away. Aarti Bhengra said that a job as a guard could help her earn more. Rita Basumatary, a cook at a public school at Sagunbari who had been a witness to the human-elephant conflict in the village, said that women’s voices and perceptions are ignored in the management of the conflict.

The absence of women in the solar fence committee points to the fact that the gender impact of the problem has been ignored, say researchers. Sayan Banerjee said that he has participated in many NGO-community meetings on solar fence installation in Assam and only men of various ethnicities participate in these.

“When I asked women why they did not participate, they told me that either they were not informed about the meeting or were tied up in a lot of housework or they thought that there was no point in going to a meeting that few women attend. However, when the NGO asked for women-only meetings, women did participate. But those meetings were general discussions on the nature of conflict or livelihood development. So, women’s concerns or ideas were hardly taken into account while planning the fence,” said Banerjee.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.