Women Bear The Biggest Cost Of Climate Disasters In Coastal Bangladesh

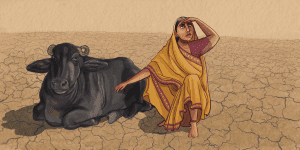

Frequent cyclones and erratic floods are increasing saltwater contamination, leading to health hazards and distressing living conditions

- Ritwika Mitra

After she got married eight years ago, Sanjita Mondal moved from her natal home in Khulna city in southwestern Bangladesh to Chilla, her husband’s village. Since then her life has been a relentless struggle against the disruptive impacts of climate change.

Chilla sits on the banks of river Pashur in the Sundarbans delta which is located across the India-Bangladesh border. The unique geography of Bangladesh anyway leaves the country prone to storm surges, cyclones, inundation and seawater intrusion. And these disasters are intensifying in frequency and intensity due to climate change.

The coastal areas, crisscrossed by a network of rivers and tributaries, now face repeated and fierce cyclones, shifting rain patterns and erratic flooding of rivers. One impact of this is increased salinity in the water used by families for drinking, cooking, bathing and irrigation.

Every year, the Mondal family’s anxieties increase – muddied, saline waters are entering their home with increased frequency, clean drinking water is becoming scarce, so is water for irrigation. Sanjita says she, her two children and husband deal with frequent bouts of bacterial infections and the mounting health bills are draining their earnings. The family survives on her husband’s erratic earnings as a fisher.

This cycle of disasters has left the family at the edge of precarity but they have no option but to deal with it. “Bhoy bhoy thaki ar ki korbo. Bhoy korleo thakte hobe, bhoy na korleo thakte hobe (I am always fearful but we have no option but to stay),” says Mondal, now 25.

Of the over 38.52 million people living along the 710-km coastline of Bangladesh, around 20 million are affected by salinity in their drinking water. This leaves the coastal population vulnerable to not just hard living conditions, but also health hazards and rising poverty levels.

“Around 13.3 million people living in coastal regions of Bangladesh are at risk due to salinity intrusion,” says Runa Khan, founder and executive director of Friendship NGO. As per the Soil Resources Department Institute (SRDI), 105.6 million hectares of land were affected by salinity in 2009, and 53% of coastal soils are salt-affected.

Friendship’s fieldwork in Bangladesh shows that saltwater contamination causes a range of problems for women – skin problems, miscarriages, and others (read here and here and here).

The Many Costs Of Climate Shift

To understand these multiple issues of livelihood and health resulting from climate change, we travelled across the Bagerhat and Khulna districts of the Khulna division.

Climate change displaced as many as 7.1 million people in Bangladesh in 2022 and may displace 13.3 million by 2050. Experts estimate that rising sea levels will submerge 17% of the country by 2050. It remains the seventh most affected country in the world when it comes to extreme weather events.

Around 3 million people live on the edges of Bangladesh’s Sundarbans, and depend on woodcutting, collecting honey, and catching fishes to survive. About 50% of them live below the poverty line.

“People are losing their homes, falling sick due to the living conditions here. When outsiders visit our villages, they refuse to even touch this water. But we are forced to use it,” says Sunita Mondal, 26, a grassroots activist in Chila village.

This study of Bangladesh’s coastal areas concludes that increased salinity in drinking water means higher chances of cardiovascular diseases, diarrhoea and abdominal pains. And households exposed to high salinity made more hospital visits than those that deal with low salinity levels, concludes this 2019 paper.

“People exposed to high salinity seemed to lack awareness regarding salinity-inducing health effects. Water salinity is a public health concern that will continue to rise due to climate change,” the study said.

Our interviews showed that children suffer from frequent bouts of diarrhoea in villages that rely on river bodies for water.

“The doctor says we need safe drinking water but we cannot afford to buy water so we boil and drink river water. But when it becomes more saline it is unfit for drinking,” says Sanjita’s husband Samaresh Gyne, 45.

Gyne earnings as a fisher are never enough to deal with the medical bills. Our interviews with small fishers in the area showed that they earn between 4000 and 5000 Bangladeshi Takas (USD 36 to 46) a month. And every visit to the doctor, who lives 3km away in Mongla, costs the family at least 500 Bangladeshi Takas. There are other expenses: buying bottled water (400 Takas) and investing annually in renovation to raise the level of their home to keep off the flood waters (roughly 1000 Takas). It is easy to see why the family is not able to save any earnings.

Fatima Begum, 19, and Sonia Begum, in her early 20s, from South Khali village are always worried about being hit by yet another bout of diarrhoea. “We can’t afford to buy water so we give boiled water to my infant,” said Fatima.

The shortage of doctors is an added burden for the people of Sundarbans, said Azrin Arobi of the Bagerhat-based non-profit, Shaplaful. “People from remote areas find it difficult to travel to the towns for treatment. There are also not enough doctors so people either self-medicate or turn to quacks for relief. The scale of the crisis is more than meets the eye. Women here often find it difficult to talk about the gynaecological problems they face,” said Arobi.

Salinity Intrusion And Reproductive Health

Sanjita has another problem she talks about once the men are out of earshot. She ‘frequently feels a burning sensation’ in the vaginal area. This is a common complaint among women of the area, she adds.

Roufa Khanum, assistant director, the Centre for Climate Change and Environmental Research (C3ER), BRAC University in Dhaka, who had conducted two research studies in the aftermath of cyclones Sidr (2007) and Aila (2009) said that anecdotal evidence showed that vaginal infections and skin diseases had spiked after the disasters.

Khanum pointed out the increasing health hazards and expenses the community bears. “There is the additional cost of a person being unable to go to work which translates to direct economic loss. Most people here are day labourers who depend on daily incomes. Then there is the unquantified, unpaid care [for those who fall sick]. Unpaid care takes an emotional toll on the primary caregiver,” she says.

Research shows a link between the climate crisis and spike in both soil salinity and river salinity in Bangladesh. Natural sources of water get contaminated further exacerbating the health conditions of the local population which rely on the water bodies for their daily activities.

Studies also show that women are facing increased threats to their reproductive health due to this. “There is anecdotal evidence based on work from local journalists in Bangladesh that there is a link between salinity intrusion and women’s health, including their reproductive health and skin diseases. [But] So far published literature in peer-reviewed scientific journals does not provide enough evidence of this,” says Iqbal Kabir, director of the Climate Change and Health Promotion Unit, Ministry of Health. “We are planning to conduct a formative research on this.”

Amita Saxena, a gynaecologist at the Delhi-government-run Lal Bahadur Shastri Hospital points out higher salt levels in water have a direct bearing on vaginal pH level. “The vaginal pH should be acidic. If there is excess salt in the water and it enters the vagina, it will alter its pH level. It will affect the vaginal tissues, and also cause a range of infections. If it persists, it can cause upper genital tract infection as well,” she says.

Excessive salt content in water will also affect the cellular stability in all parts of the body, she adds. “Once the cell is damaged, there will be decreased immunity and other consequences, including infertility,” says Saxena.

Disability Challenges

When the water level of the Bhairab river in Bagerhat town rises, Nasima Begum has to scoop up her disabled granddaughter who uses a wheelchair and put her safely on the bed. The nine-year-old’s parents have remarried and come to see her only occasionally; Nasima remains the primary caregiver. She worries about the child’s future when she is not around to care for her.

“Our house level is quite low. When the water level starts rising, I pick her up and put her on the bed. When it gets worse, her father comes and takes her home – his house is more elevated than ours. We have been taking her for health checks till she was six. But we are poor people. How can we keep the treatment going?” she asks.

Mohammad Abu Hanif Sheikh, the girl’s uncle, who drives an auto and does odd jobs says the family cannot afford good healthcare. With water levels rising, there are fewer places to seek refuge during storms and floods.

Upasona Ghosh, social anthropologist who has worked extensively in West Bengal’s Sundarbans, said that the conditions in the area are doubly problematic for the disabled. “Intersectionality is extremely important to understand how women are doubly disadvantaged when they are differently-abled. Climate change is expanding the already existing disparities in health, well-being of people. It is only by applying the lens of intersectionality can we reach out to the poorest of the poor with viable solutions,” says Ghosh.

Question Mark Over Survival

According to the World Bank, the average tropical cyclone costs Bangladesh about $1 billion annually. A third of agricultural GDP could be lost by 2050. “In case of a severe flooding, GDP could fall by as much as 9 percent,” the report noted.

Nahar Begum cooks for urban families in Bagerhat. It is becoming difficult for families to fix homes damaged by flooding and increased water levels, she said. When water seeps into homes, all that one can do is hang the family’s belongings on a tree. There can be no cooking on those days.

“Bhoy te bachi na, tension e bachi na (it is difficult to survive those days),” she says.

While Nahar makes around 3,000 Bangladeshi Taka, her son sells electric bulbs for a living. “We have no surplus cash that we would store food for those days. When we buy cattle, they die of diseases caused by stagnant flood waters. Our incomes have been so low over the years that I have not been able to save anything. There are times we do not have meals,” she said.

Barun Kanjilal, who has worked on West Bengal’s Sundarbans for three decades, said salinity intrusion has led to large-scale destruction of agricultural products. “If you look at it from a gendered lens, the burden falls on the women and they have to adapt. What happens is climatic injustice.”

When it comes to displacement, children suffer increased risks, including separation from their family, exploitation, violence and abuse, loss of education, increased vulnerability, physical and psychological trauma, says this UNICEF report. This puts displaced children at a greater risk when it comes to the impact of climate change. Bangladesh ranked 15 among countries where children were most at risk due to the climate crisis.

While speaking to this reporter, children in the area reported frequent disruptions in schooling due to the extreme weather events. Bilkis Begum asks how children can go to school if their books and bags are ruined and their homes submerged so often. She added if they raised the level of their home, the water level would surpass it next year.

“The government never looks our way,” says Shahida Begum, who lives next to the Bhairab river. A group of women, while speaking to this reporter, has a unanimous observation: “We always question ourselves ‘why do we stay here?’. But we have nowhere else to go.”

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.