[Readmelater]

Aaram Ki Jagah: Tracing Leisure Spaces For Raghubir Nagar’s Women Vendors

In this, the third in the series ‘Placing Work, Mapping Places’, we explore the many reasons why Raghubir Nagar’s women hawkers associate leisure with the safety of places of worship

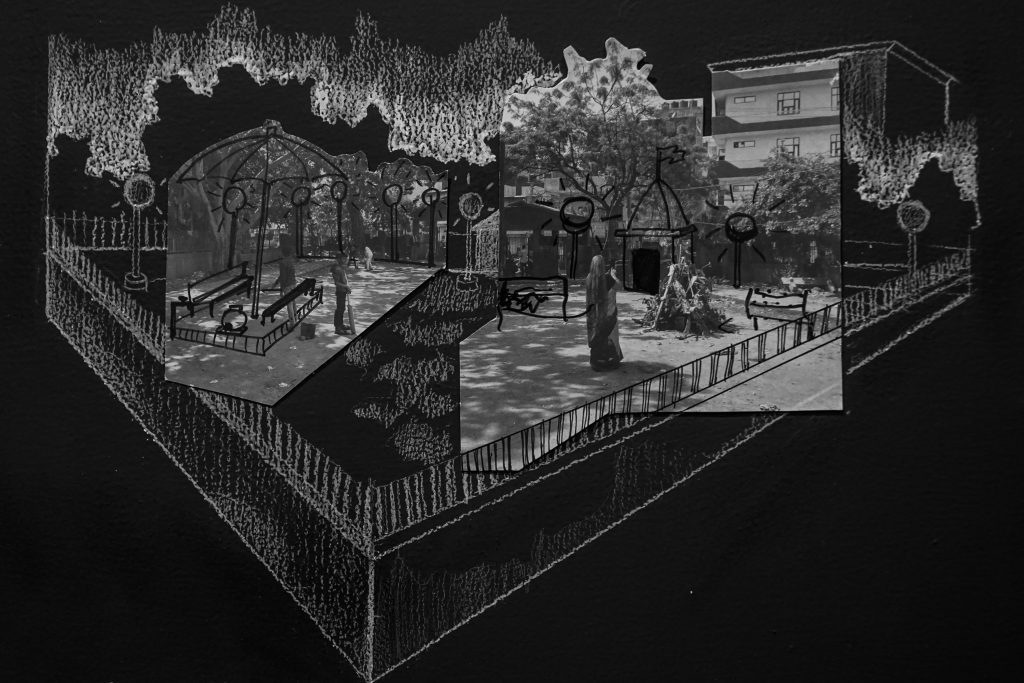

Illustration of the public scene outside the famous Ghode Wala Mandir, which women consider a landmark of pride and safety

Support BehanBox

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.