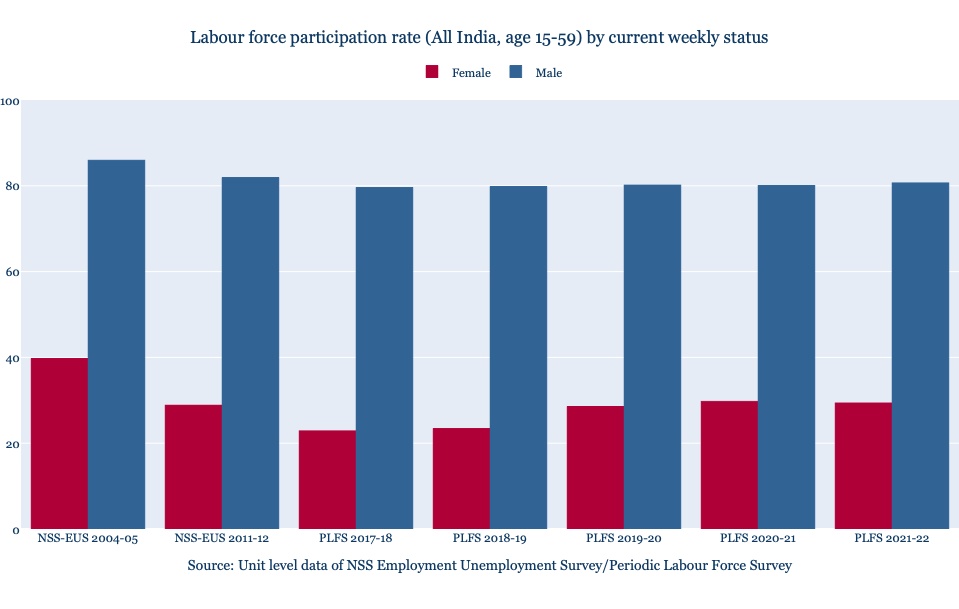

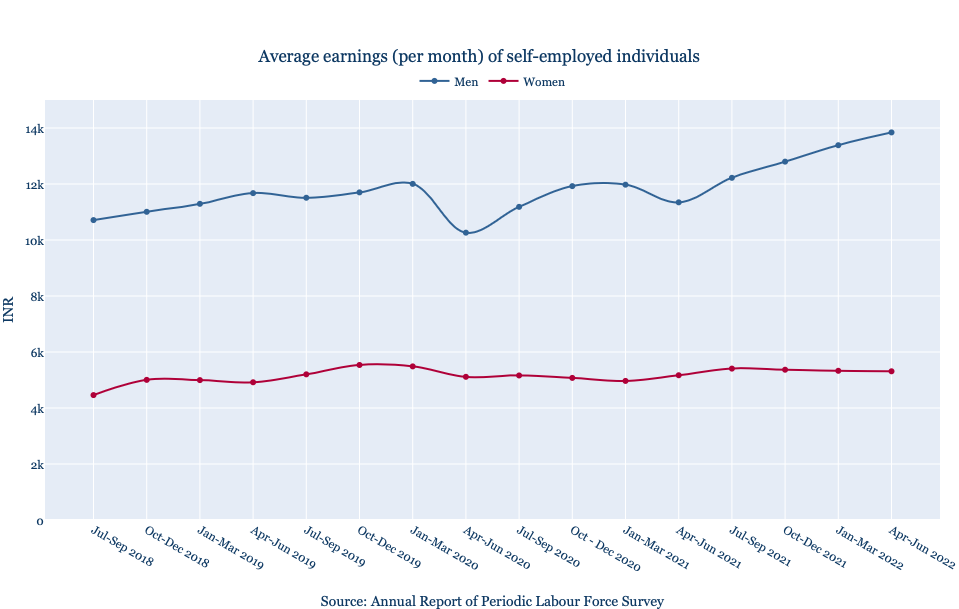

However, in recent years, women’s LFPR saw some improvement. In 2017-18, 22.9 percent of women aged 15-59 were part of the labour force. This improved to 23.4 percent in 2018-19, and saw a jump of nearly 5 percentage points in 2019-20. This period corresponds to July 2019 to June 2020, and includes the initial months of the Covid-19 pandemic when India was under a stringent lockdown brought in to check the spread of the new virus.

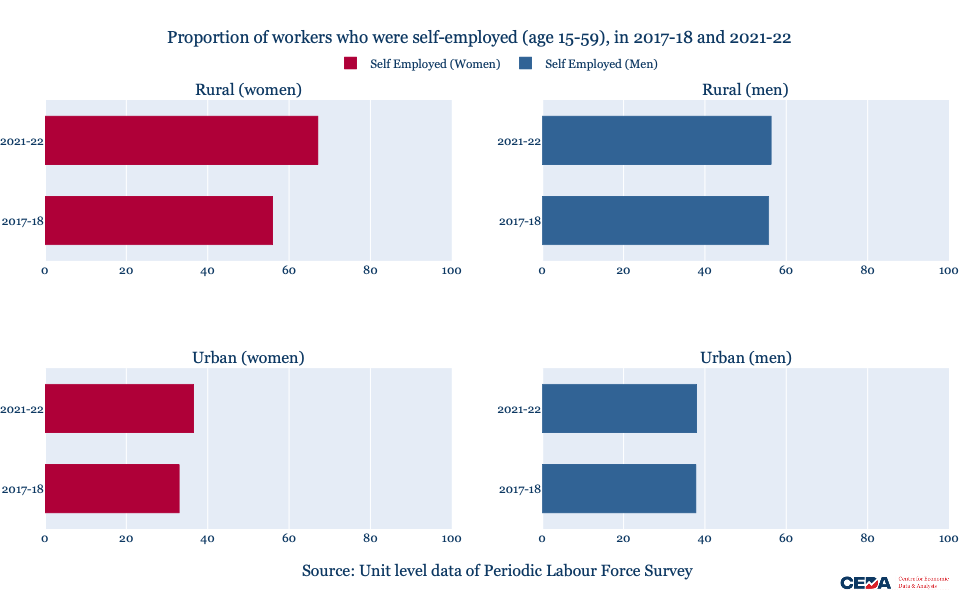

Research evidence indicates that even where women’s participation in the labour force is low, it often increases during times of crisis, indicating its counter-cyclical nature. In the 1999-2000 to 2004-05 period in India, for example, women’s participation in the labour force increased to supplement falling incomes in response to distress conditions in agriculture (Abraham, 2009). In their research, Mehrotra et al (2014) found that a large part (18 of 60 million, i.e. roughly 30%) of this increase in employment was due to rural women joining the workforce as self-employed workers in agriculture. In contrast, women quit agriculture in the high growth period of 2003-04 to 2011-12, but without an accompanying increase in non-farm employment, women’s overall LFPR fell in this period.

More recently, in their research investigating the links between pandemic income shocks and FLFPR, Ishaan Bansal and Kanika Mahajan (2021)had found that the probability of women’s employment increased in households that experienced sharp negative income shocks induced by the pandemic-related lockdowns in India. However, this improvement in women’s employment was only transitory in nature, and women’s employment started to decline once the economic situation of households improved, they found, underscoring that women’s labour often acts as an insurance during low-income periods for poorer households.

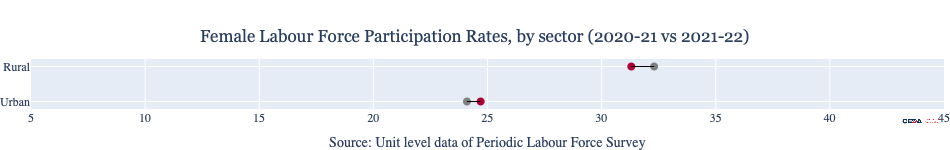

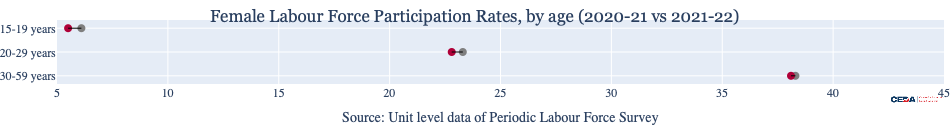

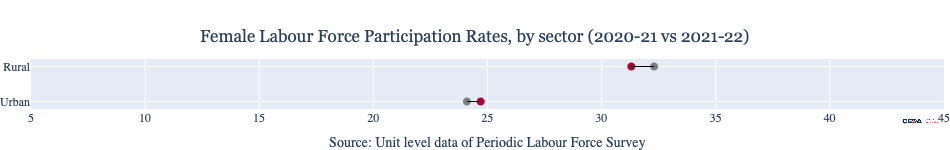

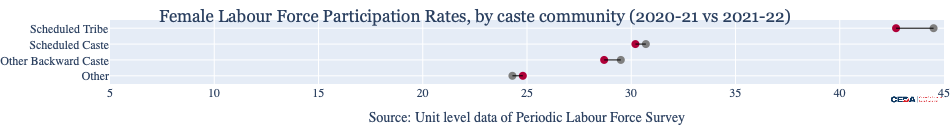

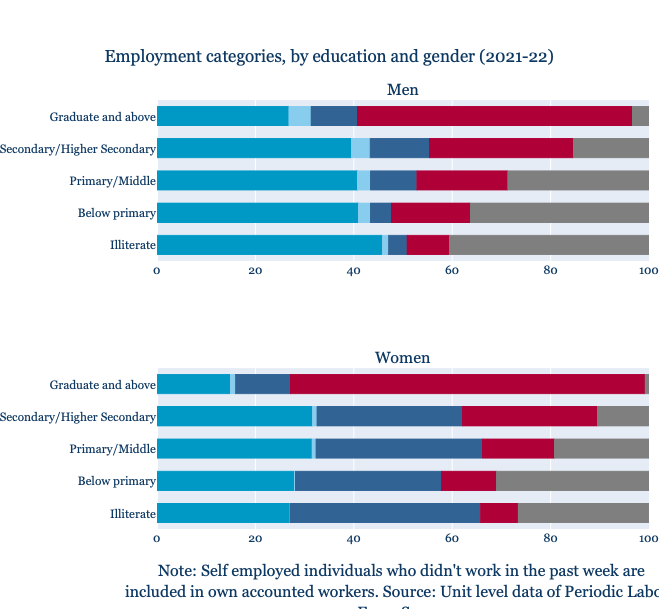

After increasing for another year, in 2021-22, the improving trend seems to have been arrested (Figure 1). However, the changes haven’t been homogenous for all women – in 2021-22, the LFPR saw small dips for rural women, women from Scheduled Tribe, Scheduled Caste, and Other Backward Class communities, as well as women who were illiterate or had primary-to-middle level of education. On the other hand, the LFPR among urban women, women with graduate (or higher) level education, or who were illiterate saw a marginal improvement between 2020-21 and 2021-22. (Figure 2)