How India’s Falling Maternal Death Rate Masks Acute Regional, Social Disparities

The steady fall in India’s maternal mortality rate over the last two decades glosses over significant variations between states, districts and social groups, show data. Poverty, marginalisation and poor systems and health infrastructure drive these inequalities, we found.

Between 2000 and 2017, India reduced its maternal mortality ratio by 60% – from 370 deaths to 145 deaths per 100,000 live births, as per the World Health Organization data. Maternal mortality ratio is defined as the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in a particular time period and can be calculated directly from data collected through vital registration systems or household surveys, as per the World Health Organization.

However, it is important to contextualise India’s figures against the significant reduction in the global maternal mortality burden in the past few decades, cautioned economist Simin Akhter Naqvi, a faculty member of Zakir Husain Delhi College.

“This [drop in maternal deaths] can be attributed to the availability of better nutritional intake owing to direct food support programmes, an increase in the number of assisted births, and a reduction in the proportion of population living below the poverty line globally. Even though the income and wealth inequalities have widened, significant percentages of the population have been pulled out of poverty over the past few decades,” she said.

India’s maternal mortality ratio stands at 96 per 100,000 live births, we estimated using the latest available data for 2020-2021 from the government’s Health Management Information System (HMIS).

However, considering the underreporting issue in some states, demographers and public health researchers suggest that the HMIS data should be used only when triangulated with data from the Census and the Sample Registration System (SRS) – an annual, national and sub-national demographic survey on health indicators, which demographers consider to be the gold-standard for mortality data.

While the latest HMIS data is available, the SRS data for the corresponding period has not been released. In the absence of that, BehanBox has decided to use the figures available from a 2022 study titled ‘Estimates And Correlates Of District-Level Maternal Mortality Ratio In India’ by Srinivas Goli and others for regional comparison. The study uses maternal death figures recorded in HMIS between 2017 and 2019 to estimate district-level maternal mortality ratio.

India’s maternal mortality ratio for the years 2017 and 2019 is 122, according to the 2022 study. This is higher than the SRS estimates (113) for the same time period.

India’s maternal mortality ratio is still far from the target set under Sustainable Development Goal – 3 – 70 deaths per 100,000 live births. The country would have to maintain an annual decline rate of at least 2.7% to achieve a national average that meets this target by 2030, noted the study. Regionally, this rate would have to be significantly higher.

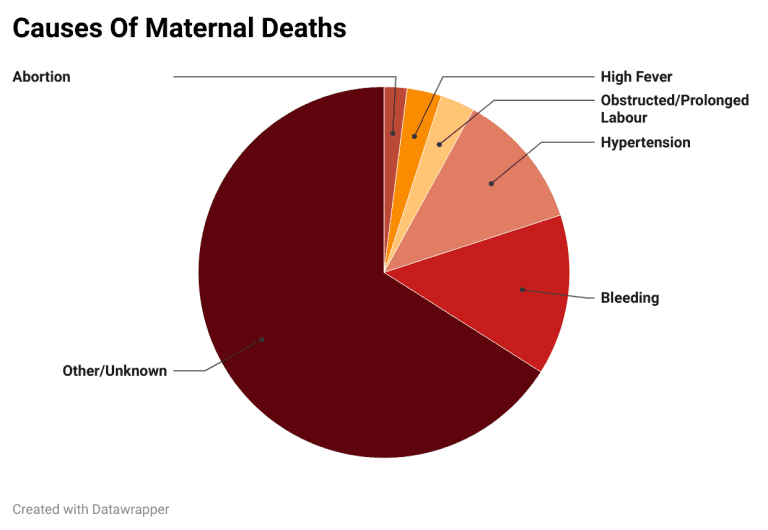

The HMIS measures maternal deaths caused due to bleeding, high fever, abortion, obstruction or prolonged labour, severe hypertension or fits, and deaths caused by other reasons including those not known. Of these, most deaths were attributed to other or unknown causes (66%), followed by bleeding (14%), severe hypertension (12%), obstructed or prolonged labour (3%), high fever (3%) and abortions (2%), according to figures from HMIS 2020-2021.

Massive gaps between states

The regional variations in the maternal mortality figures reported by India are considerable: Maharashtra fares the best (40) while Arunachal Pradesh reports the worst numbers (284), show data from the study. Among union territories, Chandigarh (15) reported the lowest burden of maternal mortality.

Upto 78% of the 36 states and union territories and 70% of the 640 districts across India report a high number of maternal deaths that are far from the Sustainable Development Goals target. In 53% of the states and union territories and 43% of all districts, the maternal mortality ratio is higher than the national average for the period 2017-19 (122).

Most districts with maternal mortality ratios higher than 200 deaths are concentrated in central, north-eastern, eastern, and northern India, noted the 2022 study.

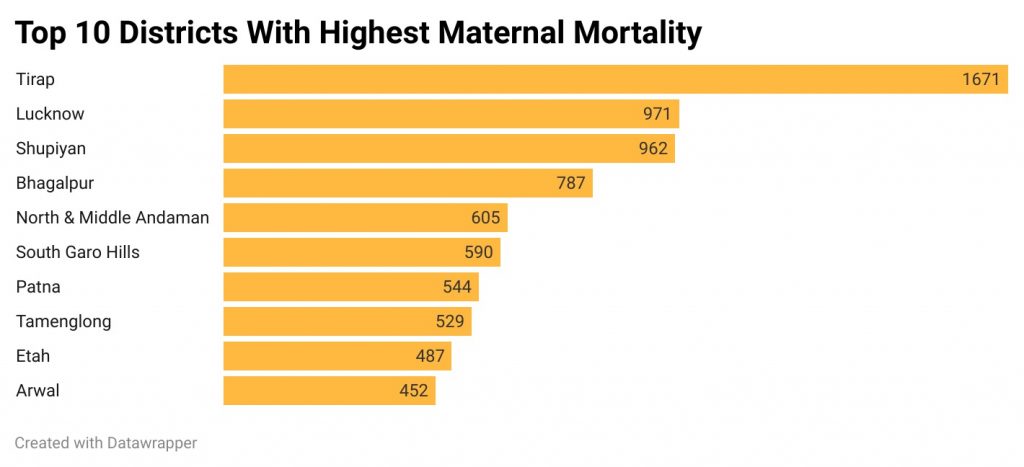

The top 10 districts with the highest burden of maternal mortality are Tirap in Arunachal Pradesh (1671), Lucknow (971), Shupiyan (Shopian) in Jammu and Kashmir (962), Bhagalpur in Bihar (787), North and Middle Andaman (605), South Garo Hills in Meghalaya (590), Patna (544), Tamenglong in Manipur (529), Etah in Uttar Pradesh (487), and Arwal in Bihar (452).

Poor health services

It is an established fact that access to quality and timely health services is important for improved maternal health outcomes. Antenatal and postnatal health checkups are healthcare services that can significantly impact maternal mortality, said Rakhal Gaitonde, a public health expert and professor at Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology in Thiruvananthapuram.

“Adequate ante-natal check ups can help in screening pregnant women for certain risk factors that lead to the possibility of dying from childbirth. Similarly, postnatal care and examination of the woman’s health in the first two days after delivery can help identify conditions that could put her at risk of death,” said Gaitonde.

India has a poor record of antenatal and postnatal care – only 30% of pregnant women can access all recommended types of antenatal care and only 81% of deliveries are followed by a health check for the mother within two days of delivery, as per the latest round of National Family Health Survey.

The percentage of women who had four or more antenatal checks was relatively higher among general caste groups (64%), followed by Scheduled Tribes (58%), and Other Backward Classes (57%). This was lowest among women from the Scheduled Castes (55%).

The percentage of women who did not undergo any postnatal checks was uniform across groups – Scheduled Castes (17%), Scheduled Tribes (16%), Other Backward Classes (15%), and Others (16%), as per NFHS – 5 data.

A look at the data on antenatal and postnatal health checks from the NFHS shows a strong correlation between access to health services and maternal mortality.

Most states and union territories that have poor access to antenatal care also record over 100 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Here are some of the poor performing states with the percentage of women who can access antenatal care: Nagaland (5%), Bihar (8%), Uttar Pradesh (11%), Arunachal Pradesh (14%),Tripura (15%), Rajasthan (22%), Meghalaya (26%), Assam (27%), Chhattisgarh (30%), Uttarakhand (31%), Madhya Pradesh (32%), Punjab (34%), Sikkim (35%), Mizoram (37%), Himachal Pradesh (45%), Manipur (46%), West Bengal (48%), Odisha (50%), and Delhi (57%).

Poor mortality rates are also reported by states and union territories where a relatively higher percentage of pregnant women can access antenatal care – the Andaman and Nicobar islands (66%), and the Lakshadweep (75%) for instance.

Most of these states and union territories – except Haryana and Lakshadweep – also have a relatively bad record of postnatal health checks for mothers within the first two days after delivery. The northeastern states do much worse than the rest of India.

The registration and monitoring programme for pregnant women often shifts the burden of accessing and availing health services on the women in need of those services, argues Gaitonde in his research paper published in 2012.

“The healthcare system pushes pregnant women to get four or more antenatal checkups during their pregnancy, without realising that the health facility may not be well-equipped or be located at a far off distance without adequate public transport. The government puts an emphasis on consumption of services while disregarding the (women’s) ability to access those services owing to patriarchal norms and other logistical reasons,” Gaitonde told BehanBox.

Among the reasons cited by men for the child’s mother not receiving antenatal care, 28% respondents cited high cost, while 15% cited that they did not allow or consider it important, and 13% cited that the family did not allow or consider it important, as per NFHS – 5 data.

While the launch and implementation of the community healthcare workers under the Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) mission in 2006 increased access to healthcare services, it also allowed authorities to shirk their responsibility and pin the blame for maternal deaths on the ASHA or the Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM), added Gaitonde.

Poor health facilities

A major reason behind the high burden of maternal mortality in India is its inadequate health infrastructure, said public health expert Gaitonde.

“These interventions [to prevent maternal deaths] require the health system to maintain certain levels of capacity in terms of human resources, technology, infrastructure or even certain emergency drugs. Health systems that are weak, have vacancies or consist of professionals who are not adequately trained, monitored and supervised, will not be able to fully execute these interventions,” he explained.

Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra are the top five states on NITI Aayog’s health index – built on 23 key health indicators including health infrastructure – for the year 2019-2020. All of these states have maternal mortality ratios below 70.

Many maternal deaths are caused by the failure of health providers to recognise post and pre-natal complications, delays in initiating appropriate treatment and the lack of emergency preparedness at health facilities, found a 2014 study, Dead Women Talking, by CommonHealth and Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, both coalitions of health activists in India.

Significant delays in accessing health services also contribute to maternal mortality, says Goli, an assistant professor at the International Institute of Population Science, Mumbai. “The higher burden of maternal mortality in hilly regions such as that of northeastern or central India can be explained by the complex terrain and longer distances to health facilities from one’s place of residence,” said Goli. This is particularly life-threatening when the mother develops obstetric complications such as obstructed labour, complications rising out of abortion or an ectopic pregnancy.

There are three common delays known to contribute to maternal deaths, according to a study conducted across nine states on risk factors associated with maternal mortality in 2020 published in the British Medical Journal. The most commonly cited is delay in inappropriate quality of care at the health facility (55.1%), lack of care-seeking (18.1%), and difficulty in reaching the facility (15.3%).

“Very often health facilities do not have beds or medicines available in times of emergency or the blood required for transfusion in case of excessive bleeding. In remote areas, doctors are not available 24×7 since many of them live in nearby towns,” explained Goli.

Patriarchy and neglect

There is an urgent need for maternal mortality to be understood as a significant indicator of gender discrimination, emphasised Gaitonde. “At each stage of a woman’s life – starting from childhood to the reproductive age – patriarchal norms result in her poor health. This then becomes the foundation on which the pregnancy occurs,” he said.

Poor maternal health also perpetuates intergenerational cycles of undernutrition, as BehanBox had reported earlier. For instance, the child mortality rate is higher (53 deaths per 1,000 live births) among children born to mothers aged below 20 years, as per NFHS – 5 data.

“Women’s diets are poorer in developing countries including India and contain limited amounts of fruits, vegetables and fish and dairy products. This causes a deficiency of key nutrients such as iron, zinc, calcium and iodine, ultimately leading to anaemia and haemorrhage – major causes of maternal mortality,” said Naqvi of Zakir Husain Delhi College. There are many instances of stillbirth or cases of new born children dying of hypertension in poorer countries due to inadequate monitoring of maternal health, as per this research paper.

Health and fertility Indicators that contribute to maternal mortality include adolescent childbearing, order of child births, nutritional intake and prevalence of anaemia among others, economist Naqvi told BehanBox. Here is a look at data points for some of these indicators from NFHS – 5.

- States with a higher percentage of births of order 3 or more – meaning higher number of pregnancies – have significantly higher maternal mortality ratio. These states are Uttarakhand (27%), Ladakh (23%), Rajasthan (26%), Arunachal Pradesh (30%), Assam (22%), Manipur (30%), Meghalaya (51%), Nagaland (34%), Mizoram (39%), Jharkhand (32%), and Haryana (25%).

- States and union territories that have a high prevalence of anaemic women, especially those who are pregnant, are also among those that record over 100 deaths. Some of these are Tripura (67%), Bihar (64%), Jammu and Kashmir (66%), Meghalaya (54%), West Bengal (71%), Odisha (64%), Jharkhand (65%), Punjab (59%), Haryana (60%), Assam (66%), and Chhattisgarh (61%).

- States and union territories that have recorded a high and increasing burden of teenage pregnancies are also among those that record high maternal deaths. These include West Bengal, Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Sikkim, Punjab, Odisha, Manipur, Delhi, and Tripura.

Adolescent pregnancies in poor and marginalised communities put women at a higher risk of maternal mortality because they are not physically strong and have poor access to nutrition and financial resources, said Naqvi. “Even if they are working, they would most likely be employed in unskilled and lower wage jobs, and would not enjoy the same financial autonomy over their earned incomes, as men,” she said.

In a highly developed state like Punjab, the consistently high burden of maternal mortality (131) could raise questions about son preference and unsafe sex-selective abortions, Goli added.

Marginalisation exacerbates risk

Marginalised groups such as Adivasis, Dalits and Muslims have to struggle for access to economic resources and education, both critical factors affecting maternal mortality, said Naqvi.

Women belonging to a Scheduled Caste or a Scheduled Tribe were found to be at a significantly higher risk of dying at childbirth in the 2020 BMJ study across nine states.

An earlier analysis of 124 maternal deaths between January 2012 and December 2013 found that upto 44% of maternal deaths were observed among women from Scheduled Tribes, 17% from Scheduled Castes and 15% from other backward classes. It also showed that more than half the deaths were recorded among women under 25 years of age.

Findings of the 2020 BMJ study show that women in the 13-19 years age bracket were at the highest risk of death in pregnancy, followed by those in the 40-49 years age group.

Health system gaps are systematically distributed in areas inhabited mostly by weaker socio-economic groups, said Gaitonde. “The 2005 Sachar Committee report discusses the way in which public services are distributed. In areas where there are larger proportions of Muslims, Dalits or Adivasis, and other groups on the axis of socio-economic marginalisation, these services are much weaker,” he said.

However, the lack of disaggregated data on maternal mortality across different caste, class, regional and religious groups conceals variations among different groups, said both Gaitonde and Goli. Disaggregated estimates also allow for increased and targeted policy interventions, added Goli.

Another way of understanding maternal deaths is conducting and analysing maternal death reviews, said Gaitonde. “Unless each maternal death is investigated to understand the journey of access to healthcare for each woman is put together and examined, these national and state-level aggregates will not give much information.”

The government launched a process of maternal death review in 2011. It is a continuous effort to identify, notify and review maternal deaths, its causes and the actions taken to improve the quality of care for preventing future deaths. States and union territories are supposed to conduct block- and district-level community-based and facility-based reviews.

The implementation of community as well as facility-based reviews was found to be poor by a 2020 study ‘Situational Analysis Of Maternal Death Review In India’.

Possible underreporting

There could be underreporting of maternal deaths for various reasons, said experts.

“Figures around maternal mortality are most likely to be underestimated due to a fear of punitive action against administrative officials as well as healthcare professionals if a death were to be investigated,” said Goli. Low reporting can also be traced to the fact that many incentives for frontline healthcare workers are based on indicators that also include maternal mortality figures, he added.

Data from health facilities do not necessarily include all the maternal deaths in an area because patients often do not even make it to hospitals and mortality data can then only be accessed from the registrar, said economist Naqvi.

Another major reason behind underreporting of maternal deaths is the lack of death registrations. Over 80% of respondents who expressed a delay in care-seeking or reaching the facility and 57% of those who expressed a delay in quality care had not registered the deaths, the 2020 BMJ study found.

Most maternal deaths across the nine states studied occurred in the antenatal period (40%), followed by intrapartum and postpartum periods. Over half the deaths in the antenatal phase were unregistered, per the study.

We believe everyone deserves equal access to accurate news. Support from our readers enables us to keep our journalism open and free for everyone, all over the world.